The Illustrated Insectopedia - Hugh Raffles (2010)

Il Parco delle Cascine on Ascension Sunday

1.

In Japan, the crickets sing in fall, giving voice to the season’s transience and its reassuring melancholies. But in Florence, writes the folklorist Dorothy Gladys Spicer in her Festivals of Western Europe, the cricket arrives in spring as a symbol of renewal, and its song is the soundtrack to lengthening days, to life lived outdoors, and on Ascension Sunday in the Parco delle Cascine, the city’s most important public park, to its very own festival.

It’s not clear whether Dorothy Spicer actually witnessed the festa del grillo herself, but she describes it vividly anyway. On the forty-third day of Easter, a warm Sunday in late May or early June, she writes, “parents pack generous lunch baskets, gather up the children, and flock to Cascine Park.” In earlier times, children hunted the crickets themselves; nowadays (this is 1958), they buy them on the festive market. It’s all so colorful: “hundreds of brightly-painted wicker or wire cages imprisoning hundreds of crickets caught in the Park, dangle from vendors’ stalls.” Traders sell all kinds of food and drink. There are red, green, orange, and blue balloons. There is music. And there is plenty of ice cream. It is, she comments drolly, “one of the happiest and gayest spring events for everyone—except the grilli!”1

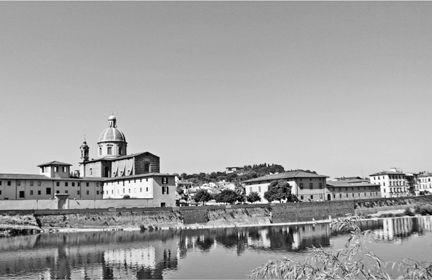

The Parco delle Cascine is no more than a thirty-minute walk along the shadeless northern bank of the Arno from the historic center of Florence. But especially in summer, it’s a very different urban space, a world away from the tourist crush of the Ponte Vecchio, the Duomo, and the Piazza delle Signoria, the iconic splendor of the Fra Angelicos, the Giottos, and the Michelangelos. The famous treasures truly are stunning individually and overwhelming in their abundance. It’s no mystery that the English and other visitors have been spellbound ever since the eighteenth-century Grand Tour made the city an obligatory destination for any of the upper class in need of an education. For good reason, the paintings, statues, and historic buildings of Florence were recognized as emblems of Western civilization centuries before UNESCO, with true Enlightenment spirit, declared the city center a World Heritage Site.

Still, even when Dorothy Spicer wrote, the intensity of cultural consumption was not what it is today. I know this because just a few years before Spicer wrote her book, my parents—young Jews abroad and somehow at ease in postwar Europe—found themselves stranded in Florence on their honeymoon after rapidly running through the £50 in cash that the British government allowed travelers to take out of the country. Those were the days before credit cards, but they got by, happily eating picnics in the hills around Fiesole, overlooking the tranquil sea of red roofs punctured by the soaring cupola of the Duomo.

Florence then was still much more the city beloved of Ruskin, Shelley, and Henry James than the one recently tagged by a jaded New York Times travel writer as a “Renaissance theme park.”2 Today, the historic center is still an extraordinary place, but now it’s part museum, part playground, and wholly commercial. Everyone browses, and so do we. The line for the Uffizi Gallery is a three-hour wait, and like Goethe—though perhaps with more regret—Sharon and I end up being bad tourists. In October 1786, early in his travels through Italy on his own version of the Grand Tour, the great writer-scientist-philosopher “took a quick walk through the city” to visit the Duomo and the Battistero. “Once more,” he wrote in his diary, “a completely new world opened up before me, but I did not wish to stay long. The location of the Bobboli Gardens is marvellous. I hurried out of the city as quickly as I entered it.”3

2.

Tucked away among the stores selling handmade gelato, handmade paper, and handmade shoes, there are shops that offer another Florentine specialty: wooden Pinocchios. Some of them are giants, far taller than the puppet-boy in Carlo Collodi’s much-loved morality tale. Collodi was born in Florence and worked there as a civil servant, journalist, and writer of children’s stories his entire life. His madcap adventure story, serialized from 1881 to 1883 in the weekly children’s magazine Giornale per i bambini, is a box of tricks that takes fairy tales (Collodi translated French ones) as well as oral narrative (he was an editor of an encyclopedia of the Florentine dialect) and the Tuscan short story, and turns them inside out to give his readers something new, something sharp and darkly funny, full of unexpected twists, and, beneath the pyrotechnics, deeply serious.

One of Collodi’s most memorable creations is the talking cricket, the grillo parlante, a rather minor character that Walt Disney Productions transformed into Jiminy Cricket. It seems significant that Florence’s most famous modern novel gave the world its most famous cricket, but I can’t say to what extent this grillo was a product of local or, more broadly, Italian lore. The Florentine fascination that produced the festamight well be just an expression of a larger national or even regional (southern European? Mediterranean?) insect intimacy.

People have kept crickets here for centuries. Little cages similar to the ones sold at the Florence festival were even found painted on the walls of houses unearthed in Pompeii. And there is plenty of linguistic evidence that noisy insects have chirruped their way far into Italian life. The connections between talking insects and human speech are audible in the many terms that cicala, the cicada, has spawned for frivolous or convoluted human chattering (cicalare, cicalata, cicaleccio, cicalio, cicalino).4 Evidence like this tells us something about the place of crickets today but only confuses their cultural location in the past. After all, modern Italian is derived in large part from the Florentine dialect nationalized by Dante, and I’m not sure that it’s possible to know precisely where this particular etymological cluster originated. Perhaps there is something unique about Florence and its crickets. Either way, the great early-nineteenth-century poet and philologist Giacomo Leopardi dignifies the notion that insect sounds are empty chatter when—along with that other southern European philosopher-poet and insect lover Jean-Henri Fabre—he explains that crickets and cicadas, like birds, sing for the joy of it, the pleasure of it, the sheer beauty of it.5

The European tradition of hearing only silliness, vanity, and a source of irritation in the cricket’s song is ancient and survives in Italy in the phrase Non fare il grillo parlante, which translates as something like “Don’t talk nonsense!” This isn’t the only tradition, of course, as these insects played an entirely different role as fixtures of the classical idyll, but it’s nonetheless the theme of the two fables of Aesop’s in which crickets appear. Collodi, who achieved fame, if not fortune, despite having grown up in profound nineteenth-century poverty, revels in subverting expectations, and his talking cricket’s words are unmistakably meaningful. Yet—and this, too, is surely biographical—the grillo parlante has a much harder time of it, a much more grittily realistic time of it, than Disney’s chirpy Jiminy Cricket. Nightmarish as the classic American remake can sometimes be (“Pleasure Island,” where kidnapped little boys are encouraged to throw off their inhibitions, was sufficiently lurid to be invoked during Michael Jackson’s pedophilia trial), Collodi’s original is altogether darker, and Pinocchio, initially a spectacularly selfish puppet-boy with no sense of the ordeals he inflicts on his destitute father, Geppetto, suffers a range of exemplary tortures, which include burning, frying, flaying, drowning, forced confinement in a dog kennel, and the more traditional transformation into a donkey.

Disney’s Pinocchio was released in the bleak February of 1940, with the shadows of war and mass unemployment darkening all horizons. Jiminy—“Lord High Keeper of the Knowledge of Right and Wrong, Counselor in Moments of Temptation, and Guide along the Straight and Narrow Path”—burst from the opening credits, a tireless spirit of can-do energy and well-judged humility who sings one of Hollywood’s most enduringly democratic lyrics, a lyric that brilliantly captures the emptiness, naïveté, and consolations of the American dream. (I wanted to quote from the song—“When You Wish Upon a Star”—but the copyright holder wanted way too much money.) Collodi’s grillo parlante was no less a virtuous insect. He urges Pinocchio to honor his father, to go to school, to work hard and practice thrift, to learn the values needed to survive in modern society. But he has tougher words for a tougher puppet, a working-class puppet in a harsh world who would have finished the story swinging by his neck from the Big Oak at the end of chapter 15 but for the outpouring of protest from appalled readers and the intervention of a savvy editor.6

The outrage saved Pinocchio, but it was too late for the cricket. As Giuseppe Garibaldi, the Hero of Two Worlds, lay dying on Caprera, off the coast of Sardinia, the grillo parlante faced his own mortality. The ailing Garibaldi, the Sword of Italian Unity, was also the founder of Italy’s first animal-protection society and a man who, as death neared, gathered his family to listen to a songbird perched on his windowsill above the crystalline Tyrrhenian Sea. Collodi, a patriotic volunteer in Garibaldi’s wars of independence and, like the father of the new nation, a critic of political corruption, social inequality, and clericalism, departed at this point from the author of the maxim “Man created God, not God man.” Perhaps it was Collodi’s disillusionment with the failure of unification to bring with it social transformation. Perhaps it was life in a hardscrabble, topsy-turvy world of insecure income and rapid social change. Or maybe he just couldn’t resist an occasion for slapstick violence. In Collodi’s universe, everyone fights for his crumbs without the privilege of species. It’s a dog-eat-dog, dog-eat-puppet, puppet-eat-dog, boy-become-donkey world in which it’s never quite clear who needs protecting from whom or even who is who. It is the scoundrel fox and the ne’er-do-well cat who string Pinocchio from the oak. By the end, Pinocchio has chewed off the blinded cat’s paw, and the starving fox has sold his own tail. And the talking cricket? With the story barely under way, in another scene that didn’t make it into the Disney movie, the grillo parlante finds himself, with scant warning, “stuck, flattened against the wall, stiff and lifeless”—speechless, too, flat as a pancake beneath the petulant puppet’s flying mallet.7

3.

Maybe there’s something in the coexistence of Disney and Collodi that helps explain a confusion surrounding the festa. Crickets have long been visible enough here to attract their own feast day; it’s just not clear whether the event exists to celebrate or demonize them—just as it’s not quite clear whether this region loves them or hates them.

For some people, the festa del grillo has a precise moment of origin: July 8, 1582, in San Martino a Strada, in the parish of Santa Maria all’Impruneta, not far from Florence. According to Agostino Lapini’s Diario fiorentino (a detailed eighteenth-century history of the city), on that day the parish organized a force of 1,000 men to save the crops from devastation by field crickets. Lapini describes a state of emergency. For ten days a crowd in the most resolute mood swarms over the fields, hunting down every cricket it can find. It fare la festa—“makes merry,” we might say—with the animals killing all it can in a feast of killing, a festival of killing, a carnival of killing. Yet no matter the many ways of killing—even mass live burial and death by drowning—“the smallest ones remained rather well,” recounts Lapini, “and because of the great heat went below ground and there made their eggs.”8

Two more crickets. The bad cricket: insect of plague and retribution, feared by the farmer. The good cricket: symbol of spring and good fortune, loved by the children. How do we get from the mob scene of 1582 to the family outing described by Frances Toor in her Festivals and Folkways of Italy, the same event that Dorothy Spicer would write about five years later? Crowds pack the Cascine; there are balloons, an abundance of food and drink, cages in all shapes and sizes; the songs of crickets fill the air; it is a day that children remember their entire lives, “the whole festa is an authentic one of color … everything is bright.” The cricket is a “harbinger of spring as it used to be for the races before them,” writes Toor, meaning for the Etruscans, the Greeks, and the Romans.

In Florence they say if the grillo you are taking home sings soon, it means good luck. My friends selected for me two males, recognized by a thin yellow stripe around the neck, because they sing most, and one of mine sang all the way home. Freeing also brings luck. I did not know that but let mine loose in the garden immediately. The happy one jumped away singing, the other silent one seemed to have been hurt but he also limped away as if pleased to be free.9

Freeing brings luck? I can’t find a convincing narrative that ties these two scenes together. Instead, there is Lapini’s blood fest of 1582 and then nothing for an entire century, no record of anything cricket related. (Were there no more plagues of crickets in the Tuscan countryside? Did those eggs never hatch? Was there no local commemoration of the mass expedition?) When crickets do reappear, it is the late seventeenth century, they are in the Cascine, and, like so much else in Florence during this period, they are firmly within the orbit of the Medicis.10

In the 1560s, Cosimo I, first Grand Duke of Tuscany, undertook the initial landscaping that created the Parco delle Cascine. He added groves of oak, maple, elm, and other shade-giving trees. The long, narrow park beside the Arno was subsequently used by the nobility as a promenade, hunting ground, and venue for outdoor entertainment—including, according to some accounts, cricket catching. Following the decline of the Medicis and the accession of the house of Habsburg-Lorraine in 1737, the park became state property. At what point the public gained full access is not clear, but open events—including perhaps the festa del grillo—were commonplace during the late-eighteenth-century rule of Pietro Leopoldo, the “enlightened” grand duke who was also the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II (and the brother of Marie-Antoinette) whose modernizing enthusiasm is evident in his sponsorship of Florence’s science museums and in the superb collections of scientific intruments that they house, collections that include both the bony middle finger of Galileo’s right hand (“This is the finger, belonging to the illustrious hand / that ran through the skies, / pointing at the immense spaces, and singling out new stars,” runs Tommaso Perelli’s inscription) and his telescope, perhaps the very one he used to sketch those washes of the moon’s phases that so inspired Cornelia Hesse-Honegger.

There is little doubt that by the end of the nineteenth century a festa del grillo was securely fixed in the spring calendar. It was a popular event, open to all and packed with picnicking families. The aristocratic tradition of the parade of the notables continued, although now led by municipal officials and culminating in the formal blessing of the city. Already it appears that rather than collecting the insects in the park, people were acquiring their crickets by buying them (along with the painted cages) from vendors who hunted up on Monte Cantagrilli (Singing Cricket Mountain) and the other surrounding hills. This shift fully into consumption sounds urban. And so does the festival’s unambiguous celebratory tone (spring renewal, good fortune, long life, and so on), a tone that also continues the aristocratic tradition of the festa as treasure hunt. Where is the uncertainty of peasant life? Where is nature, wild and dangerous? The grillo parlante has arrived. Jiminy’s on his way. The locusts are no more. Crickets are our friends.

4.

I first learned about Garibaldi’s feelings for birds and other creatures in a short book published in Rome in 1938 by the National Fascist Organization for the Protection of Animals. The architect of the Risorgimento appears in a trinity of animal lovers along with Saint Francis of Assisi and Benito Mussolini, who is quoted as urging a congress of veterinarians—apparently without irony—to “treat animals with kindness, because they are often more interesting than human beings.” Feliciano Philipp, the book’s author, explains that the new Italian state has a rational attitude toward animals, neither sentimental nor cruel. “It has instilled into every child the idea of duty towards those who are younger or weaker,” he writes. Its aim is to foster “that indulgence which is due to inferior beings.”11

Given that the Nazis’ enthusiasm for animal welfare and environmental conservation is well known, it wasn’t surprising to discover that their Axis allies also professed compassion for animals. But it was still startling to think of twentieth-century European fascists indulging, rather than exterminating, those they considered inferior. This seems like a paradox, but perhaps it results from a particular clarity about the distinction between humans and other animals. It was, after all, an area in which that giant of Western thought, Martin Heidegger, was able to offer his Nazi sponsors valuable philosophical support. Humans and others, he wrote, are separated not merely by capacity but by an “abyss of essence.”12 The difference is fundamentally hierarchical: “The stone is worldless; the animal is poor in world; man is world-forming.”13

Heidegger talks only in terms of the animal, but the encounters of everyday life are with animals in the plural and in their many guises. A greater difficulty for the fascist policy makers lay with the subhumans, those beings whose inferiority was of a different order from that of the compassion-eliciting nonhuman animals. The special problem of the Jews, the Roma, the disabled, and the rest, lay in their capacity to confuse categories, to be unnervingly proximate despite their enormous distance, to be both corrupting from within (parasitic) and threatening from without (invasive). These are beings for whom, as we know, neither of the fascist states legislated protection or indulgence. These are beings who take their place among the outcast animals as the lives not worthy of life, the vermin of both kinds.

There are other histories of animal protection. One that has always seemed significant is the convergence between the animal-welfare movement that emerged in Europe in the early nineteenth century and the abolitionist movement that campaigned in the same period to free enslaved people in the United States. The two often combined organizational resources and individual activists, and—along with the twentieth-century fascists—they shared the belief that certain forms of superiority demanded paternalist responsibility. To many members of the two campaigns, there was little distinction between transplanted Africans and domestic animals. Both elicited liberal sympathy and action. Both needed care and, perhaps, indulgence. Neither had the capacity to speak for or represent themselves. Both deserved the opportunity to labor with dignity.14

None of this is to suggest that animal-welfare advocates are still hostage to these pasts. But genealogies haunt, and unresolved dilemmas persist, and at the least, they imply caution in assuming that a caring attitude toward other beings brings with it access to moral high ground. Maybe it’s the condescension inherent in the notions of care, protection, and welfare that needs reviewing. There is much to the argument made by Isaac Bashevis Singer and many others that cruelty to animals is morally corrosive and leads readily to similar brutality toward people. Obviously, though, there is no reason to assume that kindness to animals leads equally to compassion toward people. It can just as directly cultivate the ability to discriminate between lives worth protecting and lives not worth living.

Mussolini’s state put in place an array of legislation to guarantee the security and humane treatment of a range of animals—the standard elite of pets and native species whose legal protection had already become a mark of modernity. Among the regime’s initiatives were the Fascist Act for the protection of wild animals and Article 70 of the Public Safety Act, which prohibited “all spectacles or public entertainments involving torture of or cruelty to animals.”15 This last prohibition has a particular significance for our story. Public events featuring animals are widespread in Italy, and among them is the festa del grillo. Article 70 marked the opening of a new chapter.

During the 1990s, Florence found itself a target in the nationwide drive to stop the incorporation of live animals into religious and other festivals. “No holy spirit or expression of sincere devotion gives people the right to crucify a dove in Orvieto or sacrifice an ox in Roccavaldina or slit the throat of goats in San Luca,” said Mauro Bottigelli of the Lega anti-vivisezione, a leader of the campaign.16

In Florence, activists attracted influential support. The famous scoppio del carro—the dramatic explosion of a large cart of fireworks in the Piazza del Duomo on Easter Sunday—was reworked so that the live dove bound to a flaming rocket that traditionally sparked the conflagration was replaced by a mechanical bird. Then, in 1999, the administrative district of Florence passed a law banning all commerce in wild or “autochthonous” (native) animals, a move targeting the sale of grilli on Ascension Sunday. (Did the deputies think of themselves as continuing the labors of Il Duce? I suspect most imagined a more benign lineage. If the thought did congeal, they might have drawn comfort from knowing that the fascists had no interest in crickets. Feliciano Philipp’s only reference to insects in his book is a rather dubious calculation of the quantity eaten by a pair of nesting swallows and their young in one day—6,720—a figure designed to show the birds’ importance to agriculture and public health rather than the insects’ importance to the health of the birds.)

The battle for the soul of the cricket festival took shape as a struggle between the animalisti and the traditionalists. The harm involved was perhaps less self-evident than that in the case of the scoppio—though not, I think, because the pain of a bird is more accessible than that of an insect. The question was more subtle because the relationship between Florentines and their grilli was more intimate.

All of the parties competing in this drama considered themselves pro-cricket.17 In their eventual resolution of the problem, the district government took the most pro-cricket position of all, protecting the living animals and promoting the mythical ones. Vendors were prohibited from trading in live crickets, and anyone caught selling them was to have his or her cages confiscated and the animals released to “roam freely through the hills of Florence.” But the sale of cages wasn’t banned, and the cages were not to be sold empty. To keep the cage makers in business and to retain the cultural and historical form (if not the precise content) of the event, the city provided the cricket vendors with two approved native species. One, especially handsome, was made of terra-cotta and based on a design by Stefano Ramunno, a local artist; the other, more noisy, was battery operated and produced a recognizable, if not quite authentic, “cri-cri.” You can see what the politicians were thinking: the livelihood of the local artisans was protected and even enhanced, the crickets—the live crickets—were free to roam all day and sing out without fear of capture and confinement, and the public, the cricket-loving people of Florence, could celebrate their affinities, their culture, and their history free from bad faith.

As might be expected, there soon appeared a black market in crickets, fueled by parents determined that their children would experience the pleasures of selecting a fanciful cage and its tiny occupant, carrying home their new chirping friend, releasing it in their backyard, and if they were lucky, feeling its companionship as it sang for them throughout the summer. These were deeply felt pleasures of which people were reluctant to let go. But those deputies who supported the change didn’t simply reject such tradition; they saw themselves as embracing a dynamic conception of its possibilities, a conception in which intimacies with these animals were anachronistic, archaic. Somehow, in this official pro-cricket vision, the crickets themselves, the crickets as living beings, were so incidental to the festa del grillo that there was no question that it would persist without them, as a celebration of their absence and as a celebration of the enlightened thinking which made that absence possible. “Freeing the crickets we leave behind an aspect of the past that doesn’t reflect modern sensibility, without subtracting anything from the flavor of the event at the Cascine,” Vincenzo Bugliani of the local Green Party, the deputy with responsibility for the environment, told the national press. “The tradition,” he asserted, “evolves and improves.”18 “The animalisti,” shouted a headline in La Repubblica, “have won.”

The new festa made its debut on Ascension Sunday 2001, along with a high-profile public-education campaign encouraging students to understand, honor, and respect the grilli.

Exactly five years later, full of anticipation, we left our pensione, crossed the Ponte Vecchio, and walked out eagerly along the bank of the Arno to the Parco delle Cascine and the festa del grillo, excited to know what kind of event it had become. A cricket festival without crickets. The river gleamed, placid as a pond under the bluest Tuscan sky.

5.

It was hot and humid. The air was thick and still. We’d been wandering around the park for hours. There was not a cricket in sight or earshot. Terra-cotta, mechanical, or even alive. And there weren’t any of Dorothy Spicer’s painted cages either. Were we in the right place? Had we got the date right?

As promised, there were plenty of vendors. They just weren’t selling crickets. There were toys, food, clothes, belts, caps, housewares. There were plenty of fake designer watches but not even one fake cricket. There were two long lines of stalls, tightly packed along the park’s main thoroughfare. Right in the middle, attracting the biggest crowd of all, was a large stand with sad-looking caged animals, dogs, cats, exotic birds—none wild, autochthonous, or illegal.

We walked up and down the strip yet again, then cut out to cover the park more systematically in case the cricket action was elsewhere. We stumbled upon the Fonte di Narciso, where Shelley (who elsewhere wrote of insects as his “kindred”) composed “Ode to the West Wind,” and we puzzled over a mysterious overgrown pyramid, which, we later found out, was one of the Cascine’s famous icehouses. We found the amusement park and the handsome eighteenth-century façade of the School of Agricultural Science, in which Italo Calvino studied briefly before joining the partisans. And we saw the “no thoroughfare” signs beside the market that read “Divieto di Transito per Festa del Grillo,” the sole indication that this was the event for which we’d come all the way to Florence.

But it must be somewhere, surely. We must be somehow missing it, surely. And simultaneously, we both remembered a hazy afternoon more than twenty years before when we’d stood on the terrace in front of Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre, looking out over the soothing gray panorama of Paris and trying without success, for a full ten minutes, to locate the Eiffel Tower until, all of a sudden, as if clouds had cleared, the city’s most prominent structure suddenly appeared soaring high above the landscape in the very center of our view and we couldn’t imagine how we’d failed to see it. And as that memory surfaced, we discovered that the man who runs the immaculate public restrooms in the middle of the Cascine was Brazilian, from Fortaleza, in Ceará; that he was a great conversationalist; that he was delighted to talk in Portuguese; that he had arrived in Florence thirty years ago after passing through Paris; and that, unlike the Eiffel Tower two decades earlier, the festa del grillo would not be appearing miraculously from the ether that afternoon.

So here was Seu Edinaldo from Fortaleza, full of life and energy, with just a touch of the melancholy of exile. I don’t know if he and his wife lived in the building, but they’d turned it into a tropical home, the most beautiful restrooms you can imagine, magical restrooms, all beaded curtains, whitewashed walls, cutout magazine photos of birds and landscapes, floors so burnished you could take your reflection as a dance partner. Seu Edinaldo’s family is in Rio and São Paulo, but it’s too late to go back. Oh, the saudades, the longing, the absence.

The crickets? A few years ago they changed the law and banned the sale of live crickets at the festa, he said. And since then, well, it’s not really the festa del grillo anymore. It used to be such a special day; at one time tens of thousands of people came out for it, grown-ups, children—it filled the park. Now … he gestured toward the market and the sparsely occupied lawns. On the other hand, he continued, seeing our disappointment, if you’re lucky, if you search carefully in the stalls, you might find one of the little battery-operated insects they’ve been selling for the last few years. And maybe you’ll find one of the cages, though it’s been a while since I’ve seen one, he added.

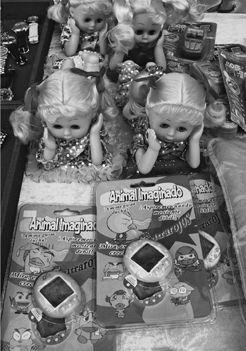

So we did look again, and this time we saw a T-shirt with a bee on it, and some painted clay ladybugs, and a diamanté (or maybe cubic zirconia) butterfly pin, and some plastic Chinese singing birds in green and gold cages that just for a second we thought held crickets, and one table with some very blond dolls and a few Tamagotchi, the lovable-egg virtual pets that were such a phenomenon in Japan in the late 1990s and which in that moment, on that table, made perfect sense as reincarnations of the grillo parlante, returned from the dead, just as he returns, without explanation, at the end of Collodi’s masterpiece.

Why so perfect? Because through the Tamagotchi—its fans claimed—young people could learn to care for other creatures, could grow to appreciate the needs of beings apart from themselves, could acquire an early intimacy with mortality and the uncertainties of life, could gain a practical knowledge of the connectedness, the pleasures, and the sadnesses of life. And it seemed serendipitous to see them here at the new festa del grillo because these claims for the Tamagotchi are exactly the same as the claims for crickets advanced by their admirers, that is, by those cricket lovers who love being around crickets, who love having a cricket as a personal friend to talk to, to listen to, to play with, to feed, and to share their house with for the summer of its life. These are the claims they used against those other lovers of crickets who are so determined to save crickets from that kind of possessive love and the confinement and loss of freedom that is its gift, who see themselves as the selfless lovers, the pure lovers, the lovers who can love without demanding anything in return, whose theme song might well be Sting’s “If You Love Somebody Set Them Free.”

But that battle was over, at least for now. There were no more crickets in the Parco delle Cascine on Ascension Sunday, and there were no more cricket intimacies to serve as the stuff of moral education and future nostalgias. There were only the Tamagotchi. And no one seemed to be buying them anyway.