The Witch's Athame: The Craft, Lore & Magick of Ritual Blades - Mankey Jason 2016

introduction

My first Witch tool was a Book of Shadows. It was a tiny little Nepalese journal that I picked up at a local head shop/hippie store. Instead of being black, it was a virtual rainbow of colors on a soft cloth cover. Its pages were handmade (at least according to the stamp inside of it), with none alike. Some of them felt like tissue paper, while others were far more sturdy.

It was a rather appropriate BoS (60S—that’s how many Witches abbreviate “Book of Shadows") for me at the time. I was kind of a tree-hugging free spirit and loved the idea of a resurgent 1960s type of counterculture. With its emphasis on the earth and the seasons, Witchcraft felt like a natural extension of what I had already come to believe as a young adult. My book was pocketsized too, and I envisioned myself scribbling in it at jam-band concerts, jotting down the sort of secrets that can only be revealed during an eight-minute guitar solo.

Though I still own that first Book of Shadows, I never did that much with it. Dreaming about its contents was far easier than creating content for it. There are a few ritual sketches inside of it, and I did transcribe a chant I learned at my first Pagan festival (a chant that is now so commonplace to me, I nearly giggled when I came across it before writing today). There's also a Christo-Pagan ritual in it, written when my first footfalls on the Pagan path were more tentative than sure-footed. On the last page of that early BoS is a call to the Inuit goddess Pinga written for a long-ago Samhain ritual.

That first BoS is a curious little snapshot of my early life as a Pagan and a Witch. There is a lot of confusion in its pages, and it contains several ideas that ended up being spiritual dead ends in my life. I like to flip through it sometimes to remind myself of how far I’ve come, but it’s not all that representative of where I am today. On the plus side, it does take me back to a simpler time in my life, which is sort of fun.

My second attempt at a Book of Shadows yielded much more fruit. That book was originally a blue leather-bound journal with a sun on the cover that I purchased at a local Barnes and Noble. Its pages were lined and uniform, and I filled much of it up over the next few years with rituals, poems, and even some handcrafted mythology. It's still my favorite BoS, and I’ve used it at handfastings (marriage ceremonies) and an assortment of rituals around the country. It contains some of my earliest coherent thoughts as a Witch and still occupies a place of honor in my ritual room.

Also important to me is my wife’s BoS (don’t worry, she doesn't mind when I flip through its pages). Her first BoS was a rather generic brown journal—there were no suns or moons on the cover of her book. When I have a question I don't know the answer to, I sometimes page through her writings in hopes of finding the information I need. Her BoS has not weathered the years particularly well and is literally falling apart at the seams.

If you were to ask my wife and me about the two most important tools we use in Witchcraft, we'd both say our athames and our books. We often refer to her first BoS and my second as "our books.” They’ve been such an important part of our journey that we feel as if they deserve a little extra recognition in our lives, even if the way we refer to them is a bit mundane.

Over the last eight years, the number of BoS’s in our house has risen dramatically. After being initiated into the Gardnerian tradition of Witchcraft (named after its founder, Gerald Gardner), my wife and I were given the first third of the Gardnerian Book of Shadows. Because Gardnerian Witchcraft is an initiatory tradition with three different "degrees,” or levels, a complete Gardnerian BoS is assembled over the course of several years as individual Witches learn new things and progress through the system.

Shortly after being initiated, my wife and I left our home of fifteen years for America’s West Coast. There we found ourselves starting a new coven not connected to any particular Witch tradition. As that particular coven grew, we built a Book of Shadows around it, composed mostly by me but also with a lot of input from other members of the coven.

Eventually I started building new BoS’s for myself, utilizing the ritual structure of our California coven (which we eventually dubbed the "Oak Court,” after the name of the street we live on). The Oak Court also does a fair number of public rituals, and both my wife and I eventually put together additional books for such occasions. As our coven continues to grow and innovate, our BoS grows along with it, with more rituals, spells, and poems becoming a part of our written legacy.

My wife and I continued our studies in the Gardnerian Craft and were initiated into the third degree of that tradition a few years after starting the Oak Court. This resulted in us receiving not only the rest of the Gardnerian BoS but also several other Gardnerian Books of Shadows from covens around the world. As covens are generally autonomous (there is no King or Queen of the Witches), each group is free to add whatever they wish to their BoS’s. This results in very different-looking books, even among Witches of the same tradition.

As of this writing, I have over fifteen different BoS's on my bookshelf, and that’s not counting the ones that are a part of traditionally published books! Each and every one of them is special and represents a different point on my ongoing journey as a Witch. Some of them I share freely with other people, while others are for my eyes only. Many of them are drastically different from their companions on my bookshelf, but all of them are Books of Shadows.

I've had a love affair with books for as long as I can remember. I find that few activities are as pleasurable and informative as reading, and this love for the printed word has extended to the Book of Shadows. I fancy myself a BoS collector these days and enjoy building new books at what's starting to feel like an annual pace. I don’t expect everyone to share my love of the BoS, but if I can capture a bit of why they are so special to me, I'll feel as if I’ve succeeded with this book.

If you are experienced at keeping a BoS, I think you’ll still find some useful information in these pages. To those of you relatively new to the Craft, I hope this book helps in the crafting of your own BoS (or BoS's!). It’s my hope that this book will shine a little bit of light on your path.

WHAT IS A BOOK OF SHADOWS?

In many ways a Book of Shadows is whatever a Witch wants it to be. Some BoS’s represent a specific tradition, while others represent a very narrow segment of a particular Witch’s beliefs, practices, or interests. If a piece of writing has meaning to a Witch (or group of Witches), it can go into a Book of Shadows.

A BoS is not a bible or an absolute. It simply documents the spiritual life of a particular Witch or Witch tradition (and everything in between). It can be public or private and doesn't even have to be a book in the traditional sense. A BoS that exists only on a hard drive or “in the cloud" is still a BoS. If someone says, "That's my Book of Shadows," then it is! It’s the most personal and varied of all Witch tools.

A BoS can be extremely organized or rather chaotic. Its contents can be decades old or fresh off the Internet. There is no right or wrong with a BoS; there is only what’s right for you. More than any other tool on my altar, my Book of Shadows represents me. It contains my rituals, my words, the poems of others that I treasure, and even my blood.

If I were going to bare my soul as a Witch to an outsider, I would pick up my most beloved Book of Shadows and hand it to them. I might use my athame more often in ritual than my BoS, but I’ve spent far more time with my book in and out of ritual than with any other tool.

While the term Book of Shadows sounds like some centuries-old magical secret, it’s of relatively recent vintage. It wasn't used to designate a “Witch book" until the early 1950s and most likely evolved outside of an established Witch tradition. It’s a lovely turn of phrase but not a particularly old one.

Even though the term Book of Shadows is less than a hundred years old, people have been writing, keeping, and producing magical texts for millennia. The history of the BoS travels from tablets to scrolls to books, and while the words we use to describe those things are different, the idea behind them is the same. An ancient Greek scroll from 2,300 years ago might not be a proper Book of Shadows, but it is most definitely related to what we do today with our BoS's.

The first BoS shared by Gerald Gardner (there's that name again—he's a pretty important figure, being the first modern public Witch) contained the rites and rituals of his Witch cult, a tradition that’s known today as Gardnerian Wicca. The actual writings in that BoS were (and are) oathbound, meaning individual Witches who receive that BoS have promised to keep its contents secret.

For several decades the only way to gain access to the rituals and rites of modern Witchcraft was to be an initiate of a Witch tradition. During that period of time (from the early 1950s to the early 1970s), a Book of Shadows served as a how-to guide for many Witches and was handed down from initiator to initiate. There were no printed Witch rituals in general circulation and no how-to books yet in print.

Initiates were free to add things to those early BoS's, and many did. BoS’s were not written in stone, and while many of the rituals and ideas passed along have stayed the same, Witchcraft has always been a dynamic and evolving faith. As a result, the original writings of Gerald Gardner have been expanded upon and added to over the last seventy years.

One of the biggest fundamental changes in Wiccan Witchcraft occurred in the 1970s, with the printing of the first Witch rituals. Now people had access to rituals without being an initiate, but this didn't remove the mystery that lies at the heart of a good Book of Shadows; instead it added additional layers and made it even easier to embrace Witchcraft. Now solitaries and eclectic groups could keep and create their own BoS's, and many initiated individuals began keeping a second (and even third) BoS to highlight the material that was now available to them in books.

YOUR BOS IS ABOUT YOU.1

I can’t stress enough how personal the BoS is. The only things that should ever go into your book are the things that resonate with you. The BoS is the one tool that we completely shape and mold around us as Witches. An athame always has to at least vaguely resemble a knife, but your BoS doesn’t have to look at all like mine or anyone else’s (and doesn't even have to be a book). It can be written in any language or not have any language at all (a book of pictures works just fine tool).

In this book I provide suggestions, along with a bit of practical advice. I'm sharing things that have worked for me and are a part of my BoS (and those of my friends), but they may not apply to everybody. Use what you want and discard the rest. Make your BoS about you and it will be just perfect!

[contents]

chapter

1

SOME DIFFERENT TYPES OF BOOKS OF SHADOWS

While there is no right or wrong when it comes to a BoS, there are a few book styles that are more common than others. But that doesn't mean every BoS will fit neatly into one of the categories outlined here. In fact, most BoS's are a combination of styles, just as most Witches are multifaceted people, so are their BoS’s.

I've arranged the following styles according to when they were first documented in modern Witch history, but just because a particular format was the first to be used doesn’t mean it’s necessarily better. A lot of Witches today start out with their own Book of Shadows before encountering one from a coven or tradition. Just as the BoS has continued to develop over the last few decades, so do individual Witches grow and change at their own pace.

The Coven Book of Shadows

The BoS I use most often in circle is my coven Book of Shadows. It contains the rites and rituals of my coven, along with a little bit of information about our beliefs and practices. I put it together myself from several different sources, and when someone is initiated into our circle, they are given a copy of the BoS.

The first tome in Witch history referred to as a Book of Shadows functioned much like my coven’s own BoS. It contained the rites and rituals of one specific group, and people were allowed to copy its rites and rituals upon being initiated. A coven Book of Shadows is a shared liturgy among Witches and represents what those Witches do when gathered together for sabbats and es-bats. The material in a coven BoS can come from a variety of sources but is generally assembled by those in the working group.

As my own coven has grown over the years, we've added some details to our coven books, such as information on where our rituals originated. We've also added some Witch material separate from rituals, some advice (such as the Wiccan Rede: An it harm none, do what you will), and some magical operations that have been particularly successful for us. A coven BoS is generally always being added to as the coven members create more things together.

A coven BoS represents the beliefs and practices of a specific Witch group. While I put my coven’s book together, it has material from many different members of our group. It’s a document for us and not any one particular person. The individual Witches in our group are free to add its contents to any other books they are keeping and to add material to their own copy of our BoS. Our particular BoS is printed in such a way that it resembles a traditional book, and we include blank pages near the end because we assume every individual Witch in our circle will want to add to their particular copy of the book.

My wife and I have begun keeping a second book for our circle, although it is not officially a part of our coven's BoS. Inside we include the names of the Witches who were at each ritual, what magical operations were performed, and any other information we think might be of importance. If our ritual includes any direct interaction with the Lord or Lady or divinatory operations, we include those too. I often think of it as our coven diary.

A coven diary is a useful little document to keep, especially if your coven engages in drawing down the moon (or sun). Drawing down involves the Goddess coming into circle through the body and voice of the high priestess and often speaking to the coven. When a goddess talks, it’s best to listen, and if you can write down what she says, all the better. The advice she offers might prepare you or the coven for future events. When the words of the Goddess come true for us, we often end up putting them in our coven’s regular BoS.

When covens are successful, they often hive off from one another, meaning that some of the Witches within it leave the mother coven and go off to start their own group, keeping the original coven’s rites and rituals. If the teachings of a coven survive over a generation and end up being transmitted far and wide, a new Witchcraft tradition is born. The BoS of a tradition is a bit different from that of a coven.

A Tradition's Book of Shadows

When a person is initiated into a tradition, they are usually given (or allowed to copy) an already existing Book of Shadows. Flipping through the pages of an initiatory line’s BoS is like going backward in time. The BoS of my tradition stretches back several decades and includes the wisdom of dozens of other Witches who have contributed to it over the years. It’s an extraordinary document and one of my most cherished Witchcraft items.

Unlike my coven's BoS, my tradition's BoS contains a wide variety of material. Since it was originally put together in an age before the “Wicca 101 book,” it contains all sorts of practical information on how to work magick and build an effective Witchcraft practice. It’s far more complete than the BoS I created for my own coven and covers many topics with a depth and breadth of understanding I’m incapable of.

In the tradition I'm a part of, our BoS can only be added to and never subtracted from. This has resulted in a book that is much larger than what it was originally when it began its life as a document for one particular coven. There's a misconception in many Pagan circles that a specific tradition’s Book of Shadows tends to be static, but nothing could be further from the truth. High priestesses are always adding to their tradition's BoS, sharing the lessons they've learned walking between the worlds while running an earthbound coven.

While tradition BoS's often contain a wide range of material that’s different from coven to coven, most groups generally preserve a group of teachings that they recognize as being core to the tradition. Core material can differ from tradition to tradition but is often made up of rituals and the tradition's earliest writings. All of the Books of Shadows dedicated to our tradition contain at least this universally recognized core material.

Traditional material is often oathbound, meaning that initiates are not allowed to share the goings-on and writings of their tradition with non-initiates (sometimes known as cowans, which is a word originally used by Freemasons to refer to the uninitiated). Sharing oathbound secrets can result in being kicked out of a traditional coven, and in some groups there are magical penalties as well. Being given a tradition’s BoS is a very sacred and serious thing and is a sign of trust and respect.

The Book of Shadows shared in a tradition is often shared in stages, especially when that tradition engages in rituals of initiation and elevation. The most common initiatory system involves three degrees. At first degree, the initiate is made a Witch of that particular tradition and generally is given a BoS full of practical material and magical advice. The BoS I was given at first degree contained none of my tradition's group rituals but did include some material advising me on how to practice as a solitary Witch.

At second degree, I was given more material to put in my BoS, most notably many of our tradition’s rituals. My high priestess and high priest believed I was ready, as a second-degree Witch, to actively assist in our coven's rituals and even lead them on occasion (with some supervision). At second degree, I wasn't ready for all the material they had to give me, because much of it applies only to Witches running their own coven.

Upon receiving our tradition's third-degree elevation, I was given the rest of our Book of Shadows. Much of that material was about how to initiate new Witches and properly run a coven. The BoS dedicated to my tradition is now in three parts, and only certain Witches who have been properly elevated can look at the second and third parts of my book.

The BoS dedicated to my tradition is currently over three hundred pages long, and that’s just the first-degree part of the book! Since it's so long, we don’t require our initiates to hand-copy our BoS; instead, we hand them what we jokingly call our forklift BoS in a three-ring binder. We are also always sure to include a few blank pages at the end in case we need to add a few more things to our BoS.

The Individual Witch ’$

Personal Book of Shadows

The most common type of BoS today is probably that of the individual Witch. A book of this type can (and probably will) contain a little bit of everything. Most Witches begin collecting information and writing down ideas long before even meeting another Witch, let alone becoming part of a tradition. My first BoS’s were of this type and contained a little bit of everything I found useful in my personal practice.

Describing an individual BoS is nearly impossible because they are all so variable, but they all tend to be less ritual-centric than the BoS’s found in covens and traditions (at least in my experience). When I put together my first few BoS’s, I tended to simply add any bit of information I found valuable or useful. Successful spells and bits of ritual went into my BoS, and I also included personal reflections post-ritual. If it felt magical, I felt comfortable putting it in my book.

One of the most liberating things about having a personal BoS is that you don’t have to answer to anybody when you put something in it. It’s possible that you might want to share the contents of your book with someone, but there’s nothing requiring you to do so. When I’m adding stuff to my coven’s BoS, I know that the people I practice with are going to end up seeing it, so I make sure that the material is clearly articulated and easy for everyone else to pick up on. In my personal BoS I can do whatever I want and be as obtuse as I desire! No one else is looking, and this can be quite liberating.

A personal BoS represents the individual Witch in a way no other tool can. Its contents are curated by you and only you! Writers like me can suggest what to put in a BoS, but they're only suggestions. The ultimate decisions are yours to make.

Even after writing a great coven BoS and picking up the BoS of my tradition. I’m still drawn to my personal Book of Shadows. There are bits that belong only in that particular book, things that only I think of as essential to the practice of a Witch.

In my days as a Witchling, I used to enjoy reading the BoS's I found included in easily available books, such as Scott Cunningham's Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. Those BoS’s make Witchcraft look so easy and organized, but they are nothing like the ones most individual Witches have. The ones from books are often too structured, too organized, and feel too much like an established tradition rather than an evolving practice. My personal BoS varies wildly from page to page. It moves from nineteenth-century English poetry to instructions on knot magick.

We Witches are always growing and finding better ways to practice our Craft and increase our knowledge. As a result, most individual BoS's become a hodgepodge of ideas, spells, and rituals. A little bit of disorganization isn't an indication of a cluttered mind; it's proof of a constantly growing mind.

As a Witch, I’m a multifaceted practitioner. I love my covens and I love my tradition, but there will always be a part of me that wants to do my own thing and have a space for my own thoughts and ideas. That’s where my personal BoS really comes into play. It is an extension of everything else I do and yet is something completely different. I’m grateful that Witchcraft offers so many possibilities.

Over the years I’ve put together many BoS's for personal use, and they vary a great deal. Some of them are just for the rituals I do in public. Often these books include my rituals in the order they were performed. Some of these books are especially decorative and impressive-looking, so I use them when performing a handfasting, a wedding, or a funeral rite. Those sorts of public rituals aren't linked to any one tradition and were generally written by me (though they often were constructed with input from happy couples and sometimes mournful family members).

I have a personal BoS that contains the things I find most important to me in my initiatory tradition. Since my Cardnerian BoS is hundreds of pages long, I have a smaller version in my own handwriting containing the elements that I think are most important to that tradition. I put it together explicitly for me, and I don’t care if anyone else can follow along with it (or read my handwriting). I think it contains the essence of a tradition I love, but what I think of as essential may not be an opinion shared by everyone in that tradition, so I keep it to myself.

Even though I wrote my eclectic coven’s Book of Shadows, I still have a separate personal BoS specifically for that circle. It contains our rituals, along with some ideas and reflections about our rituals that I don't want to share with anyone. It also looks more impressive than the version of our coven's BoS that I give to our members.

A personal BoS can and should be whatever you want or need it to be. Every Witch is different, and we all are going to cherish different things as individuals. Later in this book I'll suggest several things to put in your BoS, but in the end you should include only the material that you find valuable.

The Journal Book of Shadows

I know several Witches who keep a daily journal documenting all of their spiritual and magical pursuits that they refer to as a Book of Shadows. The majority of Witches I know do not keep a daily BoS, but I think the practice has some value. Witchcraft is a serious magical path that requires a great deal of discipline, and writing every day is a way to develop that discipline. Attempting to find something magical or spiritual on a day-to-day basis can also serve as a reminder that the wondrous often exists just outside our front door.

While most Witches don’t keep a daily magical journal, entries in a BoS about particularly meaningful and important milestones are rather important. Upon reaching the rank of third degree in my tradition, I wrote a long piece in my BoS about the experience. I wanted to capture what the ritual meant to me as a Witch and to document the symbolism of the ritual as I interpreted it at the time. Documenting the most important steps on my journey as a Witch has helped me see what I’ve accomplished over the years and just how much I still have to learn.

Many Witches like to record their sabbat experiences from year to year, and in some covens such books are mandatory. Having several years of sabbat rituals laid out beside one another is a great way to chronicle one’s progress in Witchcraft. Over the years I’ve been surprised at just how much my perceptions about certain sabbats have changed (and in some cases stayed the same).

In addition to writings about sacred rites, words about sacred spaces fit nicely into a BoS as well. I’ve never performed ritual at the Grand Canyon or Stonehenge, but being at both places helped me to feel the Witch blood pumping through my veins.

Dream journals are very popular in some Witch circles and are another version of a journal BoS. For many Witches their dreams are doorways into the subconscious and sometimes a window into the future. Scientists say we don’t remember most of our dreams, which makes writing down the ones we do remember even more important. Reviewing dreams is much like reviewing past rituals: they can tell us where we’ve been and where we might be headed.

The journal BoS is the most personal of all BoS's and, because of that, is the most difficult to write about, just remember, if something is magical to you, it’s worth jotting down. BoS journal entries don't have to go in their own book either; many of mine are positioned between rituals and spells. Most BoS’s end up being a hodgepodge of personal, coven, and group material, unless, of course, a Witch wants to create a BoS for a specific subject.

"One Specific Thing" Book of Shadows

I have a Witch friend who is an avid herbalist and gardener. She’s at her best as a Witch when she’s outside in her backyard, surrounded by the plants of her garden. Because herbology is such an important part of her life, she has a Book of Shadows dedicated to that particular practice. For most of us, a few pages in our BoS about our favorite plants is usually more than enough, but what if you want to document hundreds? That’s when a sub-ject-spe-cific BoS can be especially useful.

The most common type of “one subject only" Book of Shadows is dedicated to spellwork. Magick doesn’t just help us manifest change in our own lives; it's also how we connect with our deities and the natural world. Witchcraft is a magical religion, and to ignore magick is to miss out on all that the Craft has to offer. Keeping a book dedicated solely to spells, with a few remarks here and there on their effectiveness, makes for an especially powerful and useful type of BoS.

While magick-only books are probably the most popular type of BoS, there are all sorts of other things that might go into a sin-gle-sub-ject BoS. I keep a book full of historical Witchcraft documents that I treat very much like a BoS. The writings in it are sacred and, in most cases, oathbound, so I can share them only with a small group of people. Before writing this book, it never would have occurred to me to think of that collection as a Book of Shadows, but it most definitely is.

We all have our favorite things and our own particular areas of expertise. Keeping track of such things benefits not only ourselves but also other Witches down the road. My herbalist friend let me borrow her book once while I was constructing my own magical garden, and her advice and expertise helped make my garden that much better.

The Operative and Active Book of Shadows

A Book of Shadows should be practical, first and foremost, and while it’s nice to have a 500-page forklift BoS, it's not much fun to use in ritual. To get around this, I like to take the most useful bits of a very large BoS and turn them into what I think of as an operative Book of Shadows. An operative BoS is one that can be used easily in circle and contains all the information I need when presenting a ritual.

My operative BoS during ritual is often the CliffsNotes version of my tradition’s or coven's BoS. When performing Cardnerian ritual, for example, I take the most essential bits I need for what we are doing out of my forklift book and place them in a three-ring binder. The important part of the operative BoS in such instances are the pages I'm using to conduct the ritual, and when I’m done with whatever we’re doing that night, I take those pages out of the binder and put them back in their original home. Oftentimes the actual binder that I’m using is unimportant to me and not adorned in any particular way.

I also have a few books designed simply to be used as an operative BoS during ritual. They tend to contain the basic ritual structure for whatever coven I’m working with and omit all of the explanations and history found in my other books. Since I designed them all for me, they are also all personal BoS’s, but they are personal books with a very specific ritual purpose. It’s certainly possible to fit everything into one book, and it's great when that happens, but a BoS should be practical above all else. If yours starts growing too unwieldy, there’s nothing wrong with dividing it up or creating a supplemental book just for the things you use most often.

Recently a friend of mine sent me a copy of Doreen Valiente's original Cardnerian Book of Shadows. Valiente was one of the most important Witches who ever lived, and I love having a copy of her book on my shelf, but it's different from the books I’ve actively had a hand in creating. I will always be adding to my own books and those of my covens and traditions, but I would never add to Doreen's. It was her book, and it’s a valuable BoS that will be cherished for generations to come, but its story is complete.

Doreen’s book is what I think of as an inactive Book of Shadows: it’s a book that’s still being used but no longer being added to. The Book of Shadows that came with Scott Cunningham’s Wicca: >4 Guide for the Solitary Practitioner is another inactive book.

Cunningham designed it to be a particular way, and since he's no longer here with us, he can't change what's there or add to it. We can certainly take the words he wrote and put them in our own books and use them, but when we do so, they become something else. They become a part of our work and our traditions, and they sit next to our own BoS scribblings. And when an author makes the contents of their BoS public, that’s exactly what they hope will happen!

The BoS’s I currently write in and use during ritual are examples of what I think of as an active Book of Shadows. They are a part of my current practice and are being added to on a regular basis. That’s not true of all the BoS’s I’ve put together. My very first BoS still sits near my magical tools, but I don't plan to ever add to it again or use it during ritual.

How we categorize our books is of little consequence as long as the end result is something that speaks to the individual Witch. A good BoS is one that is used and helps the Witch better understand the broomstick they ride. Ultimately, when it comes to our personal books, we are all our own final authority.

Every Trick in the Book:

You Are Writing Your Own History

a lot of us keep Books of Shadows with the future in mind. Those of us in established traditions often pass our books to our downlines. Parents may wish to pass their books to their children. Even if you don’t intend for anyone to inherit your books, you yourself are likely to return to them again and again to measure your progress, to see how you’ve changed, or just to visit with your past.

Looking back over almost twenty years’ worth of my own Books of Shadows (and having been the beneficiary of more than one from other Witches within my tradition), I offer you this:

In twenty years, you won’t care about the text you copied word for word from that bestselling Wicca book. You won't care about the things you printed from the Internet, unaltered. Those things will serve as tiny indications of what you found interesting at the time, but they won't say much about your internal questions, your hang-ups, your beliefs, or what you were actually doing in your practice. They won’t reveal anything about you. Those words already belong to somebody else, and they’ve been copied and printed by thousands of people. They’ve already been preserved.

What the future needs is your voice, your words.

Learn to journal, whatever that may look like for you. When you perform a spell, don't just include instructions; write about your process and the results. Write about whatever book you just finished reading. Write about the people you meet. Write about what you’d like to try or what you’d like to research next. Clue in photographs of your altars, your covenmates, your ritual space, and yourself. Use paint and ink and stamps and anything else you can think of, even if you’re not much of an artist. (You might surprise yourself by becoming one!) Write notes in the margins. Collect quotes that matter to you, but then include your own commentary. Ask questions. Confess doubts. Complain. Brag. Congratulate yourself. Swear.

Copy and hoard to your heart’s content (I still do!), but don't neglect to include yourself in your Book of Shadows. That’s what’s going to matter to you in twenty years. Even if those entries are embarrassing to read later on, they’re the ones that will reveal your growth and provide the most insight into who you are and what’s important to you. And that is how you track your own progress and grow in your Craft. That is what your children will want to inherit. That is what your coven will benefit from the most. That is the history of your Craft, whatever Craft you practice.

No one ever has to read any of it, of course. But unless you destroy it, there’s always the chance that your book will end up being passed to another Witch. You are writing history—your tradition's history, your family’s history, your personal history. Don’t leave yourself out.

THORN MOONEY

Thorn Mooney is a Gardnerian high priestess, tarot card reader, teacher, and blogger who currently lives in North Carolina.

[contents]

chapter

2

Putting Together a Book of Shadows and Making It Your Own

When I began my first Book of Shadows twenty-odd years ago, I believed that everything in it had to be handwritten by me. While I continue to believe that physically writing a BoS offers some advantages, it’s not the only way to put together a Book of Shadows. I've seen all sorts of books the last few years, and every method of BoS creation has its own merits.

Finding a Book of Shadows

Finding a BoS is easier today than it’s ever been. Visit a local stationery or bookstore and you’ll be surrounded by perhaps literally hundreds of choices. People may not write with a pen and paper as often as they once did, but journals are still extremely popular (though how many of those journals are actually written in is up for debate). The downside to searching for a journal in a local book or stationery store is that their wares may not be especially "Pagan.”

There are lots of journals being produced today that look like antique books or perhaps have a moon or sun on them. For many of us that would be more than witchy enough, but if you are in the market for a BoS with a big old pentacle on it, you'll have to either shop online or visit your local metaphysical/New Age retailer. Most of my BoS’s are rather mundane-looking. More important than a giant pentagram is finding what speaks to you personally.

In addition to finding the right style for your BoS, you may want to take a second look at the circumstances in which it was manufactured. If you are fine with a mass-produced book from China, there’s no shame in that. There are BoS's like that in my ritual room. However, if you are worried about whatever residual energies might be lingering on your book, finding one made closer to home won’t get you into any trouble. (For information about cleansing, consecrating, and dedicating your Book of Shadows, see chapter o.)

In addition, there are many Witches who avoid synthetic, petroleum-based products, so check to see what your prospective BoS is made of. There are many affordable journals made today with organic ink, a nice touch for the environmentally conscious Witch. Some people swear by leather covers, while others avoid products made from animal skin. I think leather gives a BoS a nice traditional sort of look, but I understand the concerns of those who avoid animal products.

If you are a fan of leather, there are many amazing handmade journal covers out there, available at specialty shops, art shows, and online. Such covers can make the most mundane-looking BoS appear truly magical. Often these run a pretty penny, but it can be worth it if you’re planning on your BoS being with you for a lifetime.

I've met a lot of Witches over the years whose first BoS was a simple spiral notebook, the kind you find in high schools from coast to coast. There’s no shame in a one-dollar spiral notebook for a BoS, especially for the novice Witch. Its nondescript look will most likely keep wandering eyes away, and it can be taken

anywhere without raising an eyebrow. One of my first books of magical poetry was written in a spiral-bound notebook, and it still sits near my other BoS's in my ritual room today.

I think one of the most important things to think about when buying a journal or notebook to use as a BoS is whether or not the paper inside of it is lined. This may sound like a trivial thing, but if you aren’t an art major or a calligraphy expert, it can have a serious impact on the effectiveness of your BoS. My first book was unlined, which resulted in its every line looking like the text was on a major downhill run.

If you are going to put together a BoS the old-fashioned way, with pen and ink, you'll want to get a book with lines in it. Sometimes, though, the perfect book is not as perfect as we want it to be. If your perfect BoS is unlined and you need help writing in a straight line, there are some ways around the problem. Writing with a ruler is a common trick, as is lightly penciling in some lines that can be easily erased later. Of course, not all BoS's need to be handwritten ...

A Book of Shadows in a Three-Ring Binder

Some of my most cherished BoS's sit in some rather nonde-script-look-ing plastic three-ring binders. I’m not going to say they are ugly, but they look more like business manuals than collections of magical advice. Many of these books are hundreds of pages long and are full of decades of wisdom. In my initiatory tradition, some of our most carefully guarded secrets are passed via the copy machine.

While not all that aesthetically pleasing, my binder BoS is surprisingly effective. The pages are big, and most everything in it is typed out and easy to read. It's also easy to add and subtract from that particular BoS. Don't need to carry around all eight sabbat rituals at Yule? The other seven can be effortlessly removed and stored somewhere else for safekeeping.

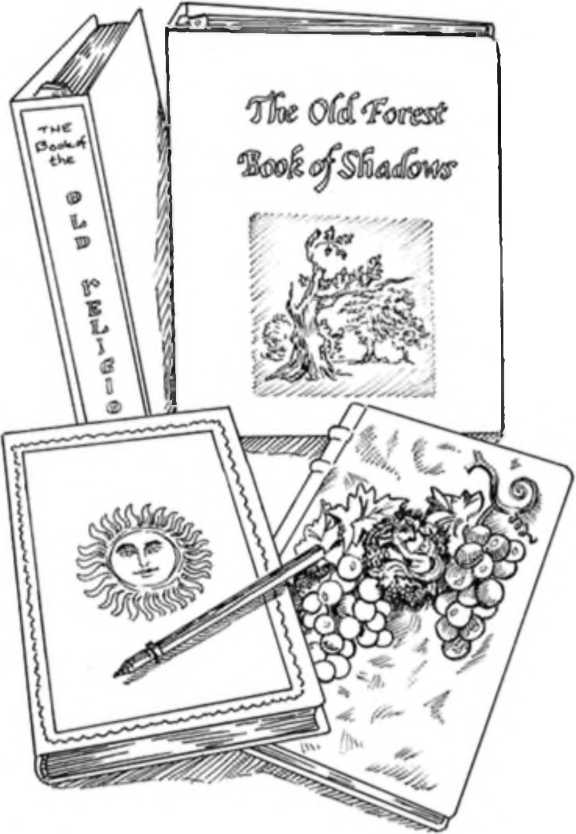

THREE TYPES OF BOOKS OF SHADOWS:

A SUN BOOK OF SHADOWS, A THREE-RING-BINDER BOOK OF SHADOWS, AND A DECORATIVE BOOK OF SHADOWS

The pages I use the most in my binder BoS are kept in page protectors. This prevents the holes punched in the paper from growing and keeps all of the pages where they belong—in my book. It's also useful if you use your BoS a lot in ritual and want to avoid getting candle wax on the pages.

Many of the things in these particular sorts of BoS’s have been handed down for decades now, often copied (and then recopied and recopied and recopied) from the sheets they were originally written/typed on. This is an amazing way to connect to history, especially when looking at fonts that really only existed in the era of the typewriter. Some of these sheets have small errors, which makes their writers more human. Flipping through a BoS that has remained mostly intact since the 1970s is a great experience.

BoS's of this style aren't reserved for covens passing down their secrets; they can be used by anyone. Since most of us today write on computers or tablets and print out those documents on standard-size paper, this is an easy way to create a BoS for those of us who enjoy typing. In addition, you can copy pictures and place them directly in your BoS this way. This is an amazingly easy way to create the perfect BoS in a relatively short amount of time.

While most of the material in my three-ring binder is generally photocopied, it doesn't have to be that way. One of the great strengths of the binder is just how adaptable it is. You can put together a binder BoS by hand-copying if that's the route you choose to go; even better is that you can use copies and handwritten material at the same time. And because page protectors are sized to fit the binder, the size of paper you use for any handwritten parts is inconsequential. If you scribble down something on a piece of notebook paper, all you have to do is drop it in a paper protector and it’ll be good to go.

The only downside to this method of BoS construction is that most binders are rather ugly, but there are some ways around that.

Making a Three-Ring Binder Look Great

There are some options out there if you want to use a three-ring binder for your BoS but don't want it to look like a corporate training manual. The first is to buy a binder with a pocket on the front that you can slip a piece of paper into. I have a few books like this with big pentagrams on them, along with the book’s title, usually the name of the coven that provided that particular BoS. There are also some nice “executive" binders out there designed to be a bit more stylish than the classic five-dollar plastic binder, but they often come in strange sizes.

An option that is a bit more elaborate is to buy a fully adorned binder from an Internet site. There are a lot of print-on-demand sites that sell binders with witchy artwork on the cover. I think a lot of these look a bit cheap, but many of them will include whatever text you want on the front—a nice option if you are trying to create a coven book in a binder and want your group’s name on it.

The Witch community has never suffered from a lack of artisans, and many of them offer homemade and elaborately adorned binder books at websites such as Etsy. Many of the artists offering such services also do custom work. Custom-made binders can range from books made using elaborate materials such as silk and semiprecious stones to books decorated with leftover Halloween kitsch.

The most personal option is to decorate a binder yourself through the use of papier-mache (or, in this case, tissue-papier-macbw). This will create an antique-looking book cover, complete with whatever symbols you might want to add, plus lots of texture. (See the last section in this chapter for tips on how to use this method.)

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Using a Three-Ring Binder Pluses

· • This is the fastest way to create a complete Book of Shadows.

“ The contents can be easily shuffled, rearranged, and added to.

“ Pages can be easily removed and put in another binder, which is especially convenient when your book grows too big for ritual.

· • Notes can be easily added in the margins.

· • Copies and handwritten pages can be used interchangeably.

Minuses

· • Three-ring binders are generally ugly and generic-looking, though there are ways around that.

“ Binders are always very big and a bit unwieldy. They don’t fit easily on bookshelves or in one’s hands during ritual.

“ In my coven we generally keep everything to the right in a binder book; we don’t use both sides of the paper. This makes the book easier to use sometimes, but it’s also wasteful.

“ Pages tear easily if they aren’t in a page protector.

Despite its disadvantages, the binder book is really appealing because it’s so easy to use. It takes the least amount of work to add to and update, which is especially convenient if your coven is just beginning or you’re just starting your practice.

HOW TO MAKE YOUR THREE-RING-BINDER BOOK

OF SHADOWS LOOK GREAT

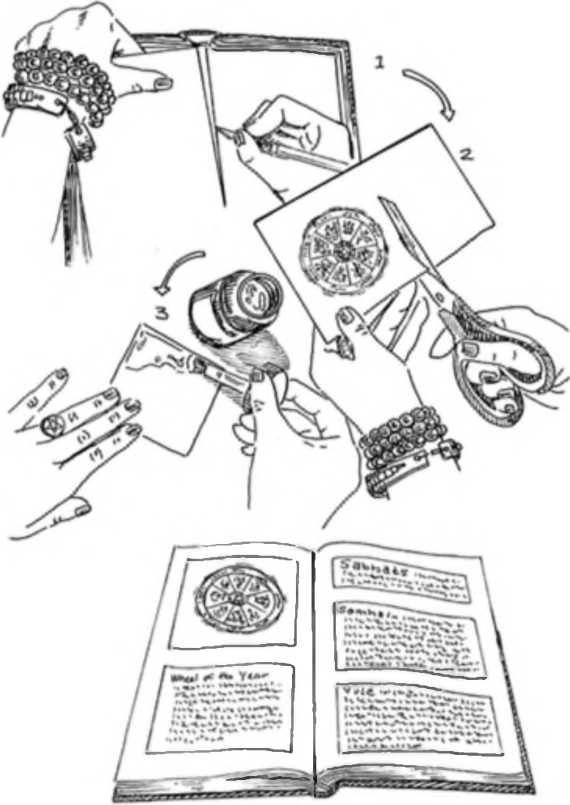

The Cut-and-Paste Book of Shadows

Some friends of mine asked me to officiate their handfasting (wedding), and I just didn't have time to write it all out by hand and stick in my BoS. Not wanting to simply read a few printed sheets of paper, I ran off a copy of their ceremony and then cut around the edges and stuck it in one of my prettiest books. No one at the service had any idea I was reading a generic Times New Roman font and had skimped a bit on my ritual preparation.

That ritual changed how I put things in my BoS’s, because from that point on I began using the cut-and-paste method about 95 percent of the time. I now have entire BoS’s filled with printed-out rituals lovingly chopped up and stuck on elegant pieces of paper. This way I get to combine the practical with the pretty.

Nearly every ritual I write these days is done on my computer. Taking all of that text and laboriously hand-copying it into a BoS does not appeal to me at all. Like many people today, I write by hand on only a limited number of occasions. To be honest, it hurts my hand to even hold a pencil or pen these days. But I can type, and I can type quickly, generally fixing any typos or grammar issues along the way. I wrote ritual by hand for a few years before the advent of the computer, so I know what it’s like, but this is much better.

If you're going to cut and paste your way to a great BoS, you'll want to reset the margins in whatever word processing program you use. Most of the books that I use with the cut and paste method are a lot smaller than a standard-width piece of paper, so resetting the margins will save you a lot of time and a lot of scissor work.

When I cut and paste, I'm almost always gluing a printed sheet of paper to an existing piece of paper in a journal. I say “gluing,” but you don’t want to use standard glue if you create a BoS this way. Glue will soak through the pages and make a mess, and tape sounds like a disaster. The best substance to use is actually rubber cement. It binds extremely well and won't leak through either piece of paper.

There are a few downsides to the cut-and-paste BoS, the biggest one being that your book will fill up rather quickly. Sure, most of the pages inside of it will be blank, but cementing all of those extra sheets inside of it will cause it to eventually puff out and it won’t want to close. This problem can be remedied by removing pages. The most precise method of page removal is to use an X-Acto knife and cut out every third page. Alternatively, you can just remove a large chunk of the book if that’s easier. A cut-and-paste BoS is one of the few instances in which a book with thin paper is preferable. There are also no second chances with this sort of BoS. If you glue in the wrong page at the wrong spot, it will probably be there forever unless you remove the entire page.

HOW TO MAKE A CUT-AND-PASTE BOOK OF

SHADOWS

My biggest problem is that I often get lost in the tedium of cutting and pasting and end up skipping a page or two. There’s nothing like thumbing through a ritual and finding pages four and five blank and wondering where the rest of your ritual is, then turning the page to find that the ritual continues on pages six and seven! These are small quibbles though, as I've found this method to be a great middle-of-the-road approach between using a binder and writing everything out by hand.

Cut-and-paste BoS creation also makes adding pictures to a Witch book much easier. I’d never use markers in a handwritten BoS due to page bleed-through, but in a copy-and-paste book that’s not really an issue. Just like with a three-ring binder, it's also possible to add a few handwritten pages to a cut-and-paste BoS if you feel the need.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of a Cut-and-Paste Book of Shadows

Pluses

· • This method combines the appealing look of a handwritten BoS with the practicality of a binder BoS.

· • This is a great book for use in ritual, compact and yet easy to read.

“ This method requires the Witch to be subjective; you won't want to put everything in a book like this.

Minuses

· • Mistakes are generally permanent unless you rip out a page.

“ Pasting pages onto pages will make your book puff out. The only remedy for this generally involves tearing out blank pages.

· • Books like this fill up quickly and are often a lot shorter than most Witches want.

Most of my public rituals go into cut-and-paste books these days. These books have some definite limitations but look nice during ritual and create the illusion that l1m using a handwritten book. Since a cut-and-paste book is fairly labor-intensive to put together, I get in a lot of good "bonding time" with my BoS while I’m filling up its pages.

1

Core ritual (quarter calls, circle casting, elemental blessings,

The Handwritten Book of Shadows

Despite my complete lack of penmanship, there is something to be said for the handwritten BoS. Taking the time to copy everything down by hand speaks to the meaning behind the words you are committing to your book. It also shows the dedication of the individual Witch. In today’s world it's easy to take shortcuts, but there aren’t a whole lot of shortcuts that can be taken with a handwritten Book of Shadows.

I'm of the opinion that while not everything in a BoS needs to be written out, it’s important to try to put at least a few rituals down in ink. I don’t think it’s necessary to write down elaborate histories or include a whole lot of exposition. In my own practice I feel that the things I really need to write down are the rituals and rites that I use the most. I also make space for a select few poems that I feel are seasonally appropriate.

My most often-used handwritten BoS contains the following items:

cakes and ale ceremony)

“ Ritual bits used frequently (Charge of the Goddess/God, drawing down the moon, chants)

· • Seasonal rituals (Yule, Samhain, Beltane, etc.)

· • Initiation and consecration rituals (includes tool blessings)

What my handwritten BoS does not contain are explanations as to the whys and the history behind those rituals. That’s all kept somewhere else. Besides, my handwritten BoS is the one I’m most likely to use in ritual, and if it were to contain five hundred pages, it would be a bit unwieldy in circle (though I'd be in much better shape if I were constantly lugging around a ten-pound BoS).

If you are going to create a handwritten BoS, I suggest making everything about the production of that book special. When my wife and I first decided to keep a handwritten book, we went out and bought some special pens dedicated to just our BoS. This sounds like overkill, but I find that using a pen (or pens) reserved for just my BoS helps separate me a bit more from the mundane world. For example, I don’t have to worry about remembering that I used one of my special pens to write a check to the electric company. And if you think using a special pen in a BoS is a bit much, I know some Witches who write their BoS’s with quill pens, the kind you have to keep dipping in ink.

In my handwritten BoS, I use three different colors of ink. Most things are written in black, but I include anything being spoken by my high priestess in blue, and any words that have to be spoken simultaneously with my high priestess are written in red. It's a pretty good system for keeping track of things in ritual, and it adds a bit more uniqueness to my handwritten BoS since all of my printed books are only in black and white.

My handwritten BoS is not particularly big (about the size of the average paperback book), and it can be a challenge to write in. Because of that, I only write on every other page, keeping the pages on the left-hand side of the book empty or reserved for pictures that are easily sketched in. I have written instructions for invoking and banishing pentagrams on the left-hand pages, located conveniently next to the written-out quarter calls and dismissals. I also use that space for drawings of altar layouts and anything else that I think might come in useful. With this system, not every page has writing on it, but most do. It also leaves me with a bit of room in case I need to go back and add something later on.

A Handwritten BoS

Presents a Few Extra Challenges

I love having a handwritten BoS, but it is a bit more difficult to put together and keep than a BoS in a three-ring binder. When I screw up something with the binder BoS, I simply take out the page with the typo on it and replace it with the corrected version. But when I make a mistake in my handwritten books, it’s forever; even using correction fluid (such as Wite-Out) will leave a scar on the page.

Some Witches try to mistake-proof their handwritten books by writing down everything in pencil first and then going over it in ink. This is a pretty good way to ensure you get everything written down correctly, but it will double the amount of time you spend working on your book. I'd like to be able to say that I recommend the "pencil first” method based on experience, but it’s something I’ve always been too lazy to do. As a result, my BoS contains a whole lot of scribbled-over words.

I wanted to end a particular handwritten BoS with one of my favorite contemporary Pagan poems. Because it was a poem I absolutely treasured, I used two different colors of ink and a very imaginative layout for it in my book. Halfway through my transcription, I realized I had forgotten an entire verse. It was all way too much to simply scribble over, so I ended up removing the entire messed-up page from my BoS. This is not a perfect solution if you make a mistake, but it does work.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of a Handwritten Book of Shadows

Pluses

· • A handwritten BoS is often the most impressive-looking option.

“ Writing everything in ink makes it highly personalized.

“ Writing words down helps with memorization.

“ The first BoS’s were nearly all hand-copied.

Minuses

· • Mistakes are generally forever or can only be corrected by tearing out a page.

“ A handwritten BoS is especially labor-intensive and may take years to finish.

· • If your penmanship is bad, it will be hard to read during ritual.

· “ A handwritten book is difficult to arrange since everything is permanent.

I reserve my use of the handwritten BoS for the most intense and personal of things. I have a handwritten copy of the most common Cardnerian rituals in one book, for example, and my most prized BoS is also handwritten. (It also has a lot of blank pages eighteen years after I started it, because I chose to write it by hand.) I love the idea of a handwritten BoS, but I don't always have the time and energy to give my handwritten books the attention they deserve.

Arranging a Book of Shadows

Arranging a Book of Shadows using a word processor is simple enough. Everything that you type can quickly be added to, deleted if you make a mistake, and moved around in dozens of ways. A handwritten BoS is completely different, and my handwritten books are full of crossed-out words and smudges that I wish were not there.

Even more importantly, a written book is generally added to over long periods of time. I’m still adding things to my second BoS, and it's been in my possession for over fifteen years now. Keeping track of that book's contents over the years has become an increasingly difficult task. For an active Book of Shadows to be useful during ritual you have to be able to find what you need in it.

It’s easy enough to mark a page with a bookmark (or, more likely, an old receipt or some other random piece of paper), but even a reasonably sized BoS might contain a few hundred pages. And besides, you have to be able to find what you are looking for just to bookmark it, and that can be a challenge if your favorite Midsummer rite is between a Goddess chant and a healing spell. How each individual Witch arranges their BoS is a very personal thing and most likely represents what they find most important in the Craft.

The focus of my books over the years has always been Witch ritual. I’m at my witchiest when I’m in a magick circle calling upon the Goddess and God as the moon rises in the sky, but that’s just me. I have friends who arrive at peak Witch by making magick and food in their kitchen. For them, it’s the practical skills of a Witch (healing, creating, and doing) that resonate most strongly. As a result, those things are given the most prominent space in their Witch books.

Over the years I’ve peeked through enough BoS’s to know a little bit about how various Witches have organized their books. The following suggestions may or may not work for you simply because the BoS is such a personal thing. Several of these methods I use myself, and what method I choose to use often depends on the context. A coven book will always differ from a personal one, and if you do end up keeping several BoS’s dedicated to specific topics, the need for organization diminishes a bit, though not completely.

Don't Arrange Anything

The easiest way to arrange a BoS (or not arrange it, as the case may be) is to not do it at all. I can’t imagine living in such a world myself (my mind generally doesn't work that way), but many Witches do so effectively. When this technique is used, a Witch simply adds whatever they want to their BoS, whenever they want, on whatever page they want. I did this with my first book, which is why it quickly became useless to me, but many Witches have much better recall than I do.

In grade school I had a teacher whose desk was always messy. Buried under piles of books and papers was a little plaque that said “Clutter is a sign of genius” (at least I think that's what it said; it was often hard to see). A cluttered book isn't necessarily a sign of a cluttered mind; it’s just a different way of doing things. And sometimes, no matter how hard you try to arrange things in a handwritten book, it’s easy to lose whatever organizational structure you are using.

It’s easy to misjudge the length of something and suddenly find that you have to split up the Yule ritual you're recording because there’s a recipe for rose water on pages you thought were blank. That sounds ridiculous, but it does happen (it happened to me). As a lover of BoS's, some of my favorite ones to read are the disorganized ones—because you never know what you’re going to find.

Similar to disorganization is just general messiness, and if you’re writing in your BoS, don't worry about it. There are no penalties for having to make an emergency notation in the margins or having to draw a long arrow from one piece of text to another because you transcribed things incorrectly. I often skip pages by accident when putting things in my BoS, leaving huge blank spaces in my books. Maybe I'll draw some pictures in those spots some day.

Chronologically

With the exception of not arranging anything at all, the easiest way to organize a BoS is chronologically. This sounds rather haphazard, but it's not as random as you might think. Our first lessons in the Craft are often some of the strongest ones, and the things put into a book in the order we learned them will reflect that. Our first invocations and magical experiments will inevitably be a bit embarrassing twelve years down the road, but they’ll also contain a passion and a fire that many Witches lose along the way.

Most of us don’t remember where we were on any given day of the year, but most of us generally remember the time of year when we first performed a specific spell or ritual. Even just "numbering" the pages of a BoS with dates of entry provides a reasonably efficient organizational structure for looking things up. As a bonus, all of your sabbat rituals will generally be in order and/or surrounded by other magical tidbits that are seasonably appropriate.

Perhaps even more so than a diary, a BoS kept in chronological order presents a complete picture of both your past and your future as a Witch. Generally, as you progress as a Witch, your spells and rituals improve and become more confident. Tracking your progress from year to year, and even decade to decade, can be a truly magical experience.

I've been lucky enough to review the rituals of several covens, and seeing how their work has changed and grown from year to year is extraordinary. Oftentimes I can tell when a new person joined the coven or a new book was purchased just by how the rituals have changed. When looking at my own work over the years, I've seen my rites become more poetic and archaic-sounding. But sometimes I need to connect with the Witch I was fifteen years ago, and looking at things as they have evolved over time is a way to do that.

In many Witch traditions the contents of the BoS are kept in the order in which they were written or created. The first few pages contain the writings of the coven’s or tradition’s founder, followed by the writings of later initiates. Oftentimes the oldest material in a book is seen as being the most important just because of its age, even if it's not very insightful in the twenty-first century. There's just something cool about coming across a fiftyyear-old piece of writing that’s never been shared outside of a particular coven or tradition!

Level of the Material

The earliest BoS’s were made up of three parts for the three degrees that were then a part of most Craft traditions. First-degree initiates were given general rudimentary information about Witchcraft. At second degree, initiates were given seasonal rites and additional material; oftentimes this marked the first time they were entrusted with Witch ritual. Finally, at third degree, the now high priestess and high priest were given all the rest of the Witch material, making their BoS complete.

Arranging a BoS by the level of its contents is generally done only in Witch traditions or covens that perform initiations, and it’s done for good reason. It’s not done this way to keep secrets from people, but to make sure each individual Witch is prepared for what lies down the road. Deity is not to be trifled or played with; it’s best to know how to talk to a goddess before performing a drawing down the moon ceremony. Books that move from basic to complex ideas do so because it's a good way to learn. (Before solving an algebraic equation, I had to learn to add and subtract.)

For Ease of Use During Ritual

Many of my ritual-only books contain complete rituals that include every word and action that I plan to say and do during a particular rite. Such books are pretty easy to use in ritual: I start at point A and proceed all the way to point Z. But most of the rituals I’m a part of with my coven aren’t set up that smoothly. I generally end up consulting several pages throughout my BoS during the course of a ritual, skipping from the beginning of my book to bits near the end. It all sounds like a lot of work, but it isn’t all that difficult as long as you know a few tricks.

Many Witches choose to set up their rituals around what I like to think of as an opening frame. They’ll reuse the same quarter calls, circle casting, and various other ritual odds and ends time and again. Having a dedicated opening/closing ritual saves a lot of space in the long run. Instead of writing down the same quarter calls for every sabbat ritual in your BoS, you only have to do it once. Our opening rites are generally longer than our workings, so this saves a lot of space in our books.

Most importantly, using the same ritual format time and again not only creates familiarity with the material but can also induce a trancelike state in the individual Witch. My coven nearly always uses the same opening frame, and when I hear it I become incredibly aware that I’m at a Witch ritual. For lack of a better term, it tunes me in to what’s going on in the circle.

The parts of ritual we use over and over again are also known and trusted to work in our circle. We don’t have to worry if they are going to be transformative or create a certain mood because we already know that we do. It also frees us up to write the working (generally the middle of the rite that celebrates the seasons, raises energy, or involves a magical operation) without having to worry about the rest of it. The only problem with this scenario is that it means I sometimes have to jump around in my BoS during ritual, which is never all that easy, especially when the only light in the room is candlelight.

My coven-ritual books are usually divided up in the following manner:

· • Opening and closing frames (including quarter calls, elemental blessings, circle castings, cakes and ale, the Great Rite, quarter dismissals, taking down the circle, and the final greeting)

· • Charge of the Goddess/God, calls to deity

· • Sabbat rituals

· • Esbat rituals

· • Chants and poems for energy raising/magick

The books we use during ritual are either operative BoS's or coven-specific ones. This means they sometimes lack a lot of the explanatory material that makes up a lot of some BoS's. Generally they have enough information to get me through the average ritual, mostly because I don't want to be holding a 400-page monster during a sabbat ritual.

The easiest (and laziest) way to mark a BoS if you are going to be jumping around in it during ritual is to use either a couple of bookmarks or a few little pieces of paper. I’ve used little bits of paper in my primary BoS for over a decade now and have only been called out on it when they have escaped from my book onto the floor. (“Littering” during ritual will usually result in a few chuckles or a couple of scowls, depending on the participants.) When I find myself going from page 12 to page 37 to page 93 to page 104 to page 199 over the course of one ritual, I'll sometimes number my little cheats or bookmarks. If you work with one book frequently, you’ll probably remember the general area where most of the ritual bits are located, but it never hurts to take a few extra precautions.

There are more imaginative and effective ways to mark things. If you use a three-ring binder as a BoS, it's easy to add tabs indicating where the different sections of your book are. Our Card-nerian BoS has tabs in it so I can easily flip from our ritual's opening parts to initiation or sabbat rites. Not only are tabs easier to use than bookmarks but you can even label them with specifics, such as "Lammas Rite” or whatever else you need to specify.

A friend of mine has a BoS divided into sections like I've outlined here, and she keeps up with the contents of her book by coloring the outside edges of the pages. The fore edge of her book looks like a rainbow. There are blue pages for chants and dances, yellow pages for sabbat rituals, and so on. It doesn't indicate exactly where everything is, but it’s a pretty unique book adornment.

Decorating and Personalizing a Book of Shadows

My first outline for this book included a section on making your own Book of Shadows. My original intention was to share how to make and bind an actual book. After reading a few books on the subject, I realized it was something I wasn’t really capable of doing, let alone writing about. So while constructing a book from scratch probably lies beyond the ability of a lot of us, there are many little things you can do to personalize your BoS.

My handwritten traditional BoS was originally just a journal purchased from Barnes and Noble but was turned into something extraordinary by a coven member who gifted it to me. He wrapped a thin sheet of leather around the cover and glued that into place. He covered up the area where he’d attached the leather to the book by placing gold leaf paper on the inside front and back covers. He did such a fantastic job that I didn’t even realize the gold paper was just meant to cover up where the leather had been glued to the book. It's that seamless.

He then decorated the cover with some iron-on grapes. The result is something that looks as if he painted directly onto the leather. Ironing decals onto leather doesn't sound like something that should work, but it is surprisingly easy to do, and the iron-ons are pretty durable. If this is something you’d like to do, just make sure you buy iron-on transfers designed for dark shirts, even if the leather you are transferring them onto is lightly colored.

On the center of the book’s cover he glued a large plastic charm depicting a satyr drinking from a large goblet. The satyr is surrounded by grape and oak leaves and is nestled directly between the iron-on transfer grapes. He tells me this was all rather simple to do, and his efforts transformed this particular BoS into a near work of art.

Sometimes all that’s necessary to turn a rather ordinary BoS into something great is a little bit of elbow grease and a few easily acquired items at a craft store. So if you find yourself feeling dismayed that your BoS is rather ordinary-looking, that can easily be changed, and you can even do it years after initially purchasing your BoS.

If you’re going to use a three-ring binder as your BoS, decorating it will present a few extra challenges. A binder is probably not something you will want to cover with leather or even high-quality paper. When the editor of this book suggested I look into papier-mache as a way to spruce up a binder BoS, I was rather skeptical, but it’s surprisingly easy to do.] I was also able to create mine with materials purchased exclusively from a local discount store.

Decorating a Binder BoS with Papier-Mache

For this project you will need the following:

· “ Regular white glue (such as Elmer's) watered down

· • Symbol printed out on paper (optional)

· • Clue gun (optional)

“ Tissue paper

“ Acrylic paints (at least two colors)

“ Spray-on acrylic sealer

• At least one paintbrush, and perhaps a fine brush if you want to add small details to your book

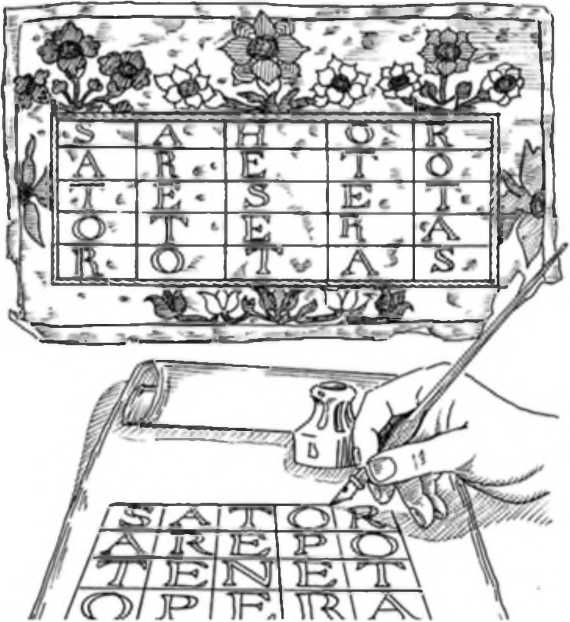

Your first step will be to decide how elaborate you want the cover of your book to be. If you want a raised (3-D) symbol on the front of your binder, start by printing out a copy of that symbol from your computer. Make sure it’s the size you want for your cover. Now trace the outline of your symbol with the glue gun (you can also simply use a bottle of glue here, though it’s a bit harder to control) and set it aside to dry. After it's dry, cut out the symbol from the sheet of paper and glue it to the front of your binder. (It will most likely take several hours for the glue to dry completely.)

Step two involves applying the papier-mache to your book. This can be a very messy process, so I suggest doing it outside or covering up your workspace with newspaper. There’s also a pretty good chance that you’ll get glue and/or paint on your clothes, so I suggest wearing items that can handle a stain or two.

Start by applying a thin layer of watered-down glue to the outside of your book (three parts regular glue to one part water). If you are scared of getting glue on your hands, you can use a brush or a rag here, but the easiest way to do this is with your hand. Using your fingers like a squeegee, remove any excess glue from your binder.

While the glue is still wet, apply a few pieces of tissue paper to your binder. You don’t have to cut out your pieces; just rip some off and put them down. The pieces of tissue paper will attach to the binder with lots of creases and crinkles and will resemble old, cracked leather. If the pieces of tissue paper overlap a little bit, don’t worry; that just adds to the effect. Take some extra time to "push down" on the tissue paper around any 3-D design you may have added. You should be able to see your design clearly even though it’s covered up by the tissue.

While the tissue paper is still wet, paint over it with an acrylic paint. Acrylic paint contains plastic, so not only will it cover the tissue paper but it will also act as glue—holding everything together. Once your book is covered in acrylic paint, leave it to dry. If you are in a hurry, you can speed up the drying process by putting your book out in the sun or placing it near a fan.

If you added a 3-D symbol to your cover, you can paint over it to make it really pop. If you didn't add the raised symbol suggested at the start, you can paint a symbol onto your binder now if you choose to. This is also a good time for any touchups, if you missed a spot or two in your initial painting. You can also paint a title on the spine of your book at this time, though that can be more difficult than it sounds.

After any touch-ups you made have had time to dry, you'll want to seal your book with a spray-on acrylic sealer. This will preserve your book and prevent the paint from peeling off at a later date. I suggest two coats of sealer just in case.

I like to make sure my BoS’s are easy to identify when they are on my bookshelf, so I generally add a few pieces of decorative tape to the binder’s spine once the sealer has dried. You can also add other adornments here, such as lace or ribbon, but tape works best, especially if you want to write out the name of your book on the binder's spine (“Jason’s Oak Court Book of Shadows,’’ for example).

I will readily admit to not being artistic at all, and I was able to make a really cool-looking book cover using this method in just a few hours (and most of those hours were spent waiting for things to dry). This technique is surprisingly effective and durable and makes my binder BoS’s feel a lot less clinical.

The most important part of any BoS is functionality, and it really doesn’t matter just how “pretty" your book is. Many of my most useful BoS's sit in rather undistinguished binders, their mundane appearance hiding their magical secrets from all but the sharpest Witches. If you like to hold on to your secrets, sometimes “plain” has its advantages.

Every Trick in the Book:

No-Fear Grimoire Grafling

the book of Shadows—the Witch’s grimoire. These names conjure up the image of a massive tome of a book, elaborately decorated, bound in tooled leather, finely illustrated and inscribed with calligraphy, dating back centuries. It's easy to get sucked into the romance and allure of the grimoire as it’s pictured in movies and described in stories. Just the thought of it is enough to excite any practitioner! Yet at the same time, the prospect of filling a blank book of your own could fill you with dread that you could mess it up. Instead of aiming to create a timeless treasure, an illuminated work of art, I want you to picture something a tad more practical: the family cookbook.

In my own family, this book is a mass-produced, ubiquitous red-and-white book published sometime in the 1970s by Betty Crocker, Better Homes and Gardens, or some other popular homemaker’s magazine. It's stuffed with index cards, clippings, and bad photocopies, with pages marked, full of notes, cross-outs, and changes. The spine is worn, and there’s clear evidence of past mishaps in the kitchen. It tells the tales of favorite recipes, experiments, and wishes. This seemingly ordinary book is sacred in that it holds the cooking experiences of my family— my mom, grandmom, and myself. It’s a work in progress, a growing, changing hodgepodge of stuff—which is exactly how you should view your Book of Shadows!

Your BoS should be an active, working collection of your thoughts, a place to gather your ideas and collage your favorite images and inspirations, a book that gets wax spilled on it during this candle spell and wine spilled on it during that esbat. It’s not the physical beauty of the book that makes it special or sacred, but the collection of experiences you gather upon its pages. There will be evidence of things that worked as well as things that failed. Your BoS is a record of your favorite chants, songs, and quotes (and do write or note the source, because as much as you’re sure you will remember, you won't), as well as the dates, occasions, and names of the folks you’ve practiced with.

While you can certainly craft a beautiful book from scratch or purchase an elaborate specialty book, there’s nothing wrong with starting with an ordinary blank book, sketchbook, or notebook. They’re inexpensive, and you can create a library of them as you fill them up. You may also find it more freeing to work with a binder, to which you can add pages as you go. No matter how you go about crafting your book, what’s most important is that you make your mark on it—and document your journey as you go. In the end, it will be just as magical as that fantastical book of fiction, if not more so!

Laura Tempest Zakroff

Laura Tempest Zakroff is a professional belly dancer, artist, and writer.

[contents]