The Trumpet of Venus (Tuba Veneris) - Dee John 2010

Cxi]

Prefacefrom the 'Translator

twas with profound pleasure and gratifcation that I accepted the task of producing the frst English translation of the Tuba Veneris. It is not often one is able to render the goddess of love such a service, and I am humbled to have

been given the opportunity.

Although there are three known MSS of the "Tuba" and a 1794 printed edition in Latin and German, I made the translation from the typescript Latin text given in Joerg M. Meier's German translation and commentary (Das Buechlein der Venus ["Libellus Veneris Nigro Sacer"]: Eine magische Handschnfi des 16. Jh. Bonn, 1990). Meier edited his Latin text primarily from Warburg MS FBH510, which is the oldest extant. His edition includes an apparatus criticus, and as might be expected the later MSS show various nonsensical variations from the

Warburg, whence they probably derive. Very rarely does

Meier reject the Warburg attestation for that of one of the later MSS.

Early magical texts are notoriously pseudepigraphical. The authorship of the Tuba Veneris has been ascribed to John Dee, for the author gives his name as Dee in the text itself. There is, however, much room for doubt. In the above cited volume, Meier lays out the case both for and against Dee as the author.

Meier gives several points leading to suspicion of forgery. The first of these is that all the surviving manuscripts, including the earliest Warburg MS, were produced on the Continent, as evidenced by the script; thus Dee's autograph is not recognizable as his own. Moreover, there is no reference to the "Tuba" in any of Dee's diaries or other surviving writings. Another point against Dee as the author is the fact that the date of the text's composition is given as June 4, 1580, and the place given as London—this, although Dee's private diary states that he was at his home in Mortlake on June 7 and most probably on June 3 as well. There is also the question of why such a text should have been written in London and not Mortlake, where Dee's magical and alchemical experiments had been taking place in any event. Moreover, June 4 was a Saturday and not a Friday, even though the latter day would be more appropriate for the composition and consecration of a book dedicated to Venus. A final consideration is that the type of magic in the "Tuba" is of a nigromantic variety in as much as it involves forcibly evoking and binding spirits, whereas the magic that Dee was practicing during the 1580's was of a more religious nature, with prayer as its basis and pious supplication

of God's holy angels as its central method.

For all of that, Meier admits, the Latin is of the good neoclassical style, with very few Medieval words (I note that it is similar in that respect to the Latin in Dee's Propaedeumata Aphoristica et al. ); furthermore, the Warburg MS can be dated to around 1600, give or take twenty years, placing it within the span of Dee's lifetime. Meier also notes that few forgeries give an exact time and date of composition as does the "Tuba".

Another interesting point here is that Dee did have a certain affection for the Angel ofVenus, a fact which Meier also notes: "Deutlich wird ebenfalls eine gewisse Vorliebe Dees fuer den Engel der Venus—dem er rffenbar einen besonderen Abschnittinseinem... Buch of Famous and Rich Discoveries widmete.” Moreover, Dee's diaries do show that Dee and Kelly were wont to pester the angels on occasion for help in finding buried treasure, one of the goals of the "Tuba". Finally, there is the consideration that most pseudoepigraphical forgeries were attributed to magicians either partially or wholly mythical, or else long dead; the "Tuba", however, was likely written in Dee's own lifetime, when he was being somewhat defamed and slandered as a necromancer, but still not nearly as well-known or likely a candidate for reputed authorship of a forgery as Solomon, Agrippa, or Faust. Ultimately Meier concludes that if it is a forgery, it is a highly unusual one, probably written by a Continental author in all likelihood familiar with the person of Dee and somewhat familiar with his magical pursuits.

I personally am forced to agree with Meier that the weight of the evidence leans against Dee as author, but that there is at present no final conclusion to the matter. We may now

say a few things about the content of the text itself, and my translation thereof.

The operative magic the text describes contains many elements that will be familiar to modern day lovers of the magical arts—the use of the circle, the burning of the seals of the spirits to compel obedience, the blowing of a trumpet before calling the spirits (cf. The Key if Solomon), the author's exhortation that the operator be stern and resolute and not let himself be cozened by the spirits or reduced to haggling with them, etc.

Meier gives a detailed analysis and commentary of the text in his edition, to which the reader is again referred. His opinion is that the Tuba Veneris as a whole stands in the tradition of Agrippa, pseudo-Agrippa, and the Heptameron of Peter of Abano ("Der Text...steht weitgehend in der Tradition des IVBuches der Occulta Philosophia Agrippas und das Heptameron des Pietro de Albano.")

The actual names of the spirits are similar to those found in the "Herpentil" and the Libellus St. Gertrudis, and in fact Meier believes that the compiler of the "Herpentil" is using the "Tuba" as his source for these names ("Dies bestaetigt den bereits oben geauesserten Verdacht, das es sich bei diesem Text um eine relativ junge Kompilation handelt, so das man den Libellus Veneris mit Sicherheit als das weit aeltere Werk wird bezeichnen duerfen, das sehr wahrscheinlich eine Quelle fuer den Kompilator des Herpentilgeliefert hat.’’’) The barbarous names of evocation found in the conjurations are also very similar to those found in these works. The sigils of the spirits appear to be derived by a similar method as given in Agrippa for deriving the sigils

of planetary spirits and intelligences (“Agrippa erklaert [III.30] eine Art der Bildung von Sigillen mittels einer kryptographischen Methode... Der Grundtypus solcher Figuren ist dem des vorliegenden Sigills sehr aehnlich.")

Finally, a note on my translation itself. Since our text is a practical magical manual and not a literary work, I have opted to give a fairly literal translation. It should also be noted that I have maintained the author's capitalization of certain words.

I wish to thank Professor Frank T. Coulson of the Ohio State University for his consideration and assistance in preparing this translation. His instruction in paleography and post-classical Latin has been most helpful.

Michael A. Putman

July 20, 2004 London, Canada

[xv]

[XVII]

The Magic of the Tuba Veneris

ibellus Veneri Nigro Sacer, or 'Tuba Veneris, is undoubtedly one of the most mysterious texts of ritual magic that has thus far come to light. Attributed to the renowned English magus and mathematician, Dr. John Dee, the grimoire

sets itself apart from the highly formulaic literature of ritual magic by possessing subtle hints of genuine artistic merit and a profound understanding of the more cerebral, Classically learned magical theory of Agrippa et al. Within the context of a work on ritual magic the text conveys attitudes symptomatic to the rebirth of Classical learning that characterised the Renaissance and whose legacy even now influences European culture.

Upon frst reading the text everything we see raises more questions than answers. Who exactly is this 'Black Venus'? Did John Dee really compose the ritual? What exactly are the

natures of the 'daemons' that are discussed within the text? What do the barbarous words of their invocations signify? The Tuba Veneris may be a short work, but it is an enigmatic one. In spite of its brevity it is a work of no mean depth, some of which I hope to cast light upon by way of this introduction.

John Dee and the Solomonic Tradition

The Tuba Veneris exists in several manuscripts, of which the Warburg copy is thought to be the oldest? Although the manuscript probably dates from the first half of the 1 71h century, possibly even being composed toward the end of Dee's life, the flowing hand preserved in the manuscript is certainly not that of Dee.

Aside from the graphological differences, there is significant documentary evidence that indicates the attribution to Dee is spurious.2 It is well known that Dee was extremely concerned about having his name connected with dubious magical practices. His particular interest in Cabalistic and alchemical works had not gone unnoticed amongst his contemporaries, most notable among them John Foxe author of the monumental and immensely popular Actes and Monuments of the Church (1563). Discussing the trial and martyrdom of Archdeacon John Philpot, Foxe refers to Dee, who was one of the examiners in the case, as 'the great Conjuror'? This incensed Dee and it seems that he took the opportunity to rebuff his critics in his Preface to Euclid (1570), where he interrupts his discussion of thaumaturgy to rail against those who confuse natural magic with sorcery and conjuration? A similar vindication against

such rumours is the cornerstone of his Discourse Apologeticall (1599), which proclaims to be "a plaine Demonstration, and feeruent Protestation, for the lawfull, sincere, very Jaithfull and Christian course, if the Philosophical studies and exercises, of a certain studious Gentleman. "5

In addition to this Dee, toward the end of his life, petitioned James I to allow him to prove such continued allegations fallacious in a court of law. 6 This indicates that defamation by way of connection with superstitious magical arts was a lifelong concern. It seems doubtful, therefore, that he would sign his name on a document that so explicitly deals, as we shall see, with the conjuration of evil spirits. It seems far more likely that the 'Tuba Veneris was the work of a 17th century author, who, being acquainted with Dee's reputation and having a superficial understanding of his magical work and interests, added his name as a stamp of authority upon his text,?

The pseudepigraphic attribution of magical works is a regular feature of the genre of grimoire literature. Almost invariably these works are attributed to some learned and respected historical figure to lend authority to their contents. Often Solomon is alleged to be the author, and indeed, one of the oldest known examples is the 'Testament if Solomon, which dates from between the 15t and Sri centuries AD, while works from Coptic Egypt from around the same period also employ similar attributions, claiming figures such as Moses, Thoth, the Apostles, even Jesus and Mary themselves as the authors of magical tracts. 8

By the time we reach the period in which the 'Tuba Veneris was probably composed, the early 17th century, we find many comprehensive works circulating in manuscript form that are

attributed to favourite ancient authorities such as Solomon, Hermes and Ptolemy, along with more recent figures such as Peter d'Abano and Cornelius Agrippa.9 The 'Tuba Veneris bears the hallmarks of a text that derives from these traditions, although this is coupled with the Classical learning so evident during the Renaissance and Baroque periods-in particular the streams ofNeoplatonic thought that Agrippa disseminated to his magically-minded audience via the Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Whereas many so-called Solomonic texts are variants on older works, compilations or simply 're-brandings' under the name of a different authority, this short text presents an entirely novel synthesis of pre-existing magical and philosophical traditions.

Whether the 'Tuba Veneris is the work of John Dee or not, I will let the reader decide. There are some tantalising similarities with his work. There is Dee's fascination with number, and even the possibility of a cryptographic cipher as found in Trithemius' Steganographia, a work that Dee became particularly fixated upon. The powers possessed by the daemons also particularly relate to Dee's interests. There is most obviously the passing reference to fnding hidden treasure: an activity notably pursued by Dee and his scryers, although they were certainly not alone in supposing the landscape to be full of undiscovered hordes.1" Additionally navigation is mentioned, which was of keen interest to this friend of Mercator who mentions that he has written several unpublished works on the subj ect in his Discourse Apologeticall. The daemons also have powers in business and war may allude to Dee's official duties on behalf of the crown.

Finally the book is dated June 4th 1580, London. From his Private Diary it seems that Dee was indeed in the vicinity of London at that time, it being one year before his angelic experiments with Barnabas Saul and Edward Kelly would begin.

The Classical Inheritance of the Tuba Veneris

The learned magical authors of the Renaissance, among them Ficino, Agrippa and Bruno owed a great deal to the rediscovery of Classical literature, which elevated their studies beyond common conjuration, into the realms of theology and philosophy.

However, there were still magical practitioners following an earlier model, one that sought power over spiritual entities through the imitation or adaptation of liturgical ritual and the related conventions of legal language: two imposing and domineering edifices of Medieval life. The books now popularly associated with the grimoire genre, from the Clavicules if Solomon to the Grand Grimoire, generally take their approach from this particular stream of magical thought.

It is apparent from the outset of the 'Tuba Veneris that the inspirations of the author of this particular grimoire lay beyond the inheritance of post-Medieval Christendom and Biblical legend. Rather they hearken back to the magical culture of the Classical pagan world. From the first sentence alone it is apparent that this text owes a debt to the mythologies of the pagan Mediterranean: "The name Venus among the Stars was

given to me by the Gods (a Superis).”

This is to say nothing of the striking image of the frontispiece that depicts the goddess herself arrayed in a red-black mantle, holding her magical implements and standing upon an appropriately verdant patch of grass. Depicted as a fair-skinned maiden it is seems that her 'blackness' relates to her association with six nocturnal spirits, who are described as 'Infernal dwellers' in the introductory verse.

Throughout the history of myth and magic the traditional representation of Venus, or Aphrodite, has been that of a fair-haired and beautiful woman. Indeed, there may even be said to be a rough suggestion of Botticelli' s The Birth if Venus in this image. In the context of magic it was through crosspollination with Arabic astrological magic that these depictions of the gods and goddesses lost their pagan identities and became considered purely as celestial images: figures somehow impressed upon the world-soul, which could be exploited by creating talismans in their likenesses.

Such images are found in many sources, the most popular among them Agrippa' s Three Books if Occult Philosophy and the Picatrix, although there are innumerable other minor works on such astrological magic. ” Although they often refer to the talismanic image of Venus as being a naked woman none of the common sources describe the image of Venus as having a red or black mantle, nor any of the other accoutrements she is shown with on the 'Tuba Veneris frontispiece. The following example from Agrippa' s Three Books is typical of the talismanic representations of Venus:

"They made another image of Venus, the first face of Taurus or Libra or Pisces ascending with Venus, the figure of which was a little maid with her hair spread abroad, clothed in long and white garments,

holding a laurel, apple, or flowers in her right hand, and in her left a comb. It is reported to make men pleasant, jocund, strong, cheerful and to give beauty."12

Some tantalising hints as to the ultimate inspiration for the figure of the black Venus can be found throughout Classical literature. Perhaps the name is derived from the cult epithet of Aphrodite Philopannyx-"Night-loving," or "Lover of all the night". This epithet occurs in the Orphic Hymn to Aphrodite, which the Tuba Veneris author would have known, although it would probably have been in the Latin translation if he were at all familiar with the work. 13 Additionally, in his Guide to Greece, composed in the 2nd century AD, Pausanias mentions an Aphrodite Melaina-the "Black Aphrodite"-so called "due to the fact that men do not, as the beasts do, have sexual intercourse always by day, but in most cases by night."™

Furthermore, there is a Latin work that enjoyed wide dissemination across Europe from the mid-15* century onward and contains some (possibly autobiographical) information relating to the cult of! sis-Aphrodite and her stygian connections. This work is Lucius Apuleius' Metamorphoses, or The Golden .Ass. Composed at some point in the mid-to-late 2nd century AD, it tells of the bawdy adventures of the aristocratic Lucius who, by the third book, is transformed into an ass through reckless meddling with a witches' magical ointment.

In the eleventh book, Lucius desperate to turn back into a human calls upon the "blessed ff(Jieene cifHeaven," resulting in a dream vision of the goddess that ultimately leads him to become an initiate in an Egyptian cult serving Isis and Osiris. The description of the vision itself reads not unlike one of the formulae for image magic occurring in Agrippa:

"First shee had a great abundance ofhaire, dispersed and scattered about

her neck, on the crowne of her head she bare many garlands enterlaced with floures, in the middle of her forehead was a compasse in fashion of a glasse, or resembling the light of the Moone, in one of her hands she bare serpents, in the other, blades of corne, her vestiment was of fine silke yeelding divers colours, sometime yellow, sometime rosie, sometime famy, and sometime (which troubled my spirit sore) darke and obscure, covered with a blacke robe in manner of a shield.”^ Furthermore the goddess herself declares some explicit connections between not only the celestial regions, but also the underworld:

"I am she that is the naturall mother of all things, mistresse and governesse of all the Elements, the initiall progeny of worlds, chiefe of powers divine, Queene of heaven! the principall of the Gods celestiall, the light of the goddesses: at my will the planets of the ayre, the wholesome winds of the Seas, and the silences of hell be diposed; my name, my divinity is adored throughout all the world in divers manners, in variable customes and in many names, for the Phrygians call me the mother of the Gods: the Athenians, Minerva: the Cyprians, Venus: the Candians, Diana: the Sicilians Proserpina: the Eleusians, Ceres: some Juno, other Bellona, other Hecate: and principally the Aethiopians which dwell in the Orient, and the Aegyptians which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustome to worship mee, doe call mee Queene Isis."16

The connection of this goddess with agricultural deities such as Proserpina, Demeter and Ceres is telling, since such goddesses were generally considered chthonic-the germination of seeds and so forth being processes that took place beneath the earth, on the margins of the underworld. The most explicit connection between this many-named goddess and the stygian world relate to her predictions pertaining to Lucius' initiation into her cult. Lucius glosses over the exact details when he comes to recount them, but it is evident that the initiation involves a descent to the underworld, domain of the patron

deities of the sect-Isis and Osiris:^

"Thou shalt live blessed in this world, thou shalt live glorious by my guide and protection, and when thou descendest to Hell, where thou shalt see me shine in that subterene place, shining (as thou seest me now) in the darkness of Acheron, and raigning in the deepe profundity of Stix, thou shalt worship me, as one that hath bin favourable to thee, and if I perceive that thou art obedient to my commandement, addict to my religion, and merite my divine grace, know thou, that I will prolong thy dales above the time that the fates have appointed, and the celestial Planets ordeined."18

However, it is important that we do not consider the Tuba Veneris as a revival or reconstruction of ancient paganism, or even a survival of Lucius' Isis cult. Like many of the works of learned occultism that flourished in the Renaissance, the pagan aspect is somewhat ambiguous. As I have mentioned previously, the imagery of the pagan world generally became assimilated into a mechanical system of astral magic whereby the ancient myths explained the natures of the planets and gave indications as to how their virtues may be exploited.

An allegiance to this type of astral philosophy is indicated by the author of the 'Iuba Veneris who refers to his depiction of Venus as "a certain image representing thefigure if the planet." Therefore the Venus being referred to in the text is not intended as an object of pagan veneration, but is a talismanic image-an expression of the nature and influence of the planet Venus. In the ritual itself, the subjugation of the daemons occurs through the agency of Anael, the angel of the Venereal sphere, rather than explicitly via the goddess. Outside of the opening verse and reference to the "certain image", the goddess is never explicitly referred to. Such astral relationships

with the pagan gods are hinted at in Agrippa, but are most explicit in Ficino's astrological practice, which used ancient Orphic Hymns to attract stellar influence and affect the soul of the singer, rather than to call down the favour of the pagan divinities for whom they were originally composed.19

Further hints of Classicism can be found throughout the text, such as the specification that the Seal of Venus should be engraved upon Cyprian copper, an allusion to the Classical myth that Aphrodite was born at sea and came ashore at Cyprus.20 The author also demonstrates his Classical learning during the consecration of the magical book, or Liber Spirituum, for which he has composed three verses loosely in the Sapphic style. Despite the author seeming to pay -little heed to the prosody of the Sapphic form, and one of the lines being too long, this verse is still something of a novelty in the realm of grimoire literature, which usually prefer more utilitarian forms of writing, generally drawing on a Biblical 'fire and brimstone' approach.21 Since Sappho was best - known for her erotic lyrics, the Sapphic verse-form would be appropriate for a work dealing with Venereal forces.

Some of the most striking aspects of the Tuba Veneris are the numerological characteristics. The text is dominated by instances of the number six, the use of which ultimately derives from Pythagorean philosophy. Although the number seven is most often associated with Venus, the author has obsessively structured his work around the number six: the seal is six-sided, there are six daemons and the circle is six feet in diameter, and so on. The only other magical text contemporary with the work that has a comparable numerological obsession is the Heptarchia Mystica-a magical work undoubtedly by Dee,

which uses a sevenfold scheme throughout. However, the 'Tuba Veneris goes further than the Heptarchia in its meticulous employment of number.

The notion of six as a Venereal number is recorded in Agrippa's Three Books if Occult Philosophy. In his discussion of the numbers ascribed to the gods " by thePythagoreans", Agrippa states:

"The number six, which consists of two threes, as a Commixtion of both sexes, is by the Pythagoreans ascribed to generation, and marriage, and belongs to Venus, and Juno.”22

By 'a Commixtion if both sexes Agrippa is pointing out that six is, according to Pythagorean numerology, the multiplication of the frst 'masculine' number (three) and the first 'feminine' number (two). This notion of odd numbers as masculine and even numbers as feminine is recorded in part fve of Aristotle's Metaphysics

" ... there are ten principles, which they arrange in two columns of cognates-limit and unlimited, odd and even, one and plurality, right and left, male and female, resting and moving, straight and curved, light and darkness, good and bad, square and oblong.”""

It is worth notingthat this system of binary correspondences, along with Theon of Smyrna's writing on the quaternary, are the ancient templates for the systems of occult correspondences that fourished in the Hermeticism of the Renaissance/1 Most notable among these the tables in Agrippa' s Occult Philosophy ( 1531) and the later collection of magical correspondences, derivative of Agrippa, that are presented in the Magical Calendar of Frankfurt Hermeticist Johann Baptista Grosschedel (1620) .25

The number three seems to play a part of secondary importance in the text. For example, with the exception of

Amabosar, the daemons mentioned in the text have names consisting of three syllables. This means that the total number of syllables in the daemonic names comes to 19 (3+3+3+3+S+4). 19 multiplied by 6, the number of prime importance in the text, is 114-the number of syllables in three Sapphic stanzas. This may, however, be coincidence-such are the difficulties of analysing works of this nature-or it may indicate that the daemons are bound to the book through a numerological relation between their names and the verses used to consecrate it.

The Influence if Contemporary Magical Literature

As has been noted above, Agrippa seems to have been instrumental in imparting Classical influences to our author. However, Agrippa's work concentrated almost solely on the theories behind natural, astral and spiritual magic. For Agrippa to set down the particulars of practice, such as the invocations, instructions for ritual regalia and so forth would undoubtedly have been folly on many levels. Therefore the detailed instructions for practical ritual magic generally circulated privately in manuscripts, occasionally being printed where sympathetic communities flourished, such as in the Rhineland Palatinate of the 17th century^

It is evident that the author the Tuba Veneris had access to several such practical works. 'The Book if the Spirits, or Liber Spirituum, is mentioned in the Key if Solomon amongst others. However, the author's description of the book has striking similarities with the process described in The Fourth Book if

Occult Philosophy, attributed to Agrippa. Both the Tuba Veneris and the Fourth Book describe the Liber Spirituum as containing the names, invocations and seals of the spirits. Agrippa mentions binding the book between two curious apocalyptic talismans on the first and last leaves of the book, presumably indicative of divine power over --!he spirits^ Similarly, the author of the Tuba Veneris suggests that the 'character of Venus' (presumably the double-sided hexagonal seal) be drawn upon the book, alongside the aforementioned 'certain image' of the goddess, presumably with a similar purpose in mind. In addition to this, the angel Anael is called upon to impose his authority over the daemons during the consecration of the book.

Such magical books seem to have been commonplace in the toolkit of the ritual magician. Both Mathers' composite Solomonic work and Agrippa' s Fourth Book seem to indicate that the spirits will appear immediately upon opening the book and reading their conjurations^ Richard Kieckhefer, in his discussion of consecrated magical books, notes that the tradition of the Liber Spirituum was widespread by at least the 15th century and that if a magician were to fnd his rituals ineffectual then his book could be re-consecrated according to certain techniques and its efficacy to be restored. 29

Once the book has been written and consecrated Agrippa advises caution, saying that the book "is to be adorned,garnished, and kept secure, with Registers and Seals, lest it should happen aafter the consecration to open in some place not intended, and endanger the operator"Although many modern authors have claimed that the (often very lengthy and tedious) prayers and conjurations

of ritual magic should be addressed from memory, it would appear that the commonly perceived image of the magician in his circle reading aloud from a magical book is actually closest to the authentic procedure of magical evocation-at least in this instance.

The author's instruction to bury the magical implements "in the earth next to the powers of flowing water," until such time as they are required is significant. It stirs up once more the connection between Venus and the underground and is an explicit instruction to put the items in a place of Venereal influence. Agrippa provides a list of geographical features that are ascribed to the planets, amongst them:

"To Venus, pleasantfountains, green Meadows, flowrishing [flourishing] Gardens, garnished beds, stews [brothelsJ (and according to Orpheus) the sea, the sea shore, baths, dancing-places, and all places belonging to women.’’” (My italics).

The association of water with Venus again harkens back to the Classical mythology surrounding the birth of Aphrodite-the goddess was born from foam when Uranus' genitals were cut off and cast into the sea by his son, Kronos/1 Agrippa mentions Orpheus, who sings in his Hymn to Venus that she is "rejoicing in the azure shores, Near where the sea with foaming billows roars. "32

As with the Liber Spirituum, the trumpet is not a unique ritual device. It is found elsewhere in magical literature, but nowhere is it as strikingly employed as in the Tuba Veneris. One is notably used in the Key of Solomon and related manuscripts as a preparation- for the conjuration of the spirits, where it is blown to the "four quarters of the Universe"''’' The trumpet is generally an instrument associated with war, and therefore

a Martial influence. However, there is a list of the musical instruments-music being associated with Venus-in Giordano Bruno's De Imaginum Compositione, which mentions the lituus, a type of curved horn used in warfare, whose form is similar to that held by the image of the goddess, although such instruments were usually cast in brass, rather than being made of animal horn/4 The warlike nature of the horn could perhaps be interpreted as relating to the influence in war that the demons are claimed to possess. In the Tuba Veneris the horn is to be taken from a live, but presumably sedated, bull-the zodiacal animal of Taurus, whose ruling planet is Venus. After which the horn is washed with a solution of vitriol (copper sulfate) and wine vinegar. This results in a natural dye, giving the horn a blue-green tint.

The six-sided Seal of Venus itself is analogous to the Pentacle of Solomon employed in the 17th century magical text called the Goetia, as well as with the lamen prescribed by many other texts as a symbol of authority over the spirits. In both the Goetia and Tuba Veneris, the magician wears the seal, or pentacle, whilst carrying out the ritual operations. Both texts also employ the technique of applying heat to the seal of a spirit as a form of torture to encourage it to appear, or to discipline it if unruly. While the Goetia advises the use of a heated box, the Tuba Veneris recommends heating the seal itself and applying it to the wax characters of the spirits-an approach presumably used because wax is less durable than the metals upon which the Gaelic seals are inscribed.

The magical circle is a device found in almost every grimoire. The primary purpose of the circle in ritual magic

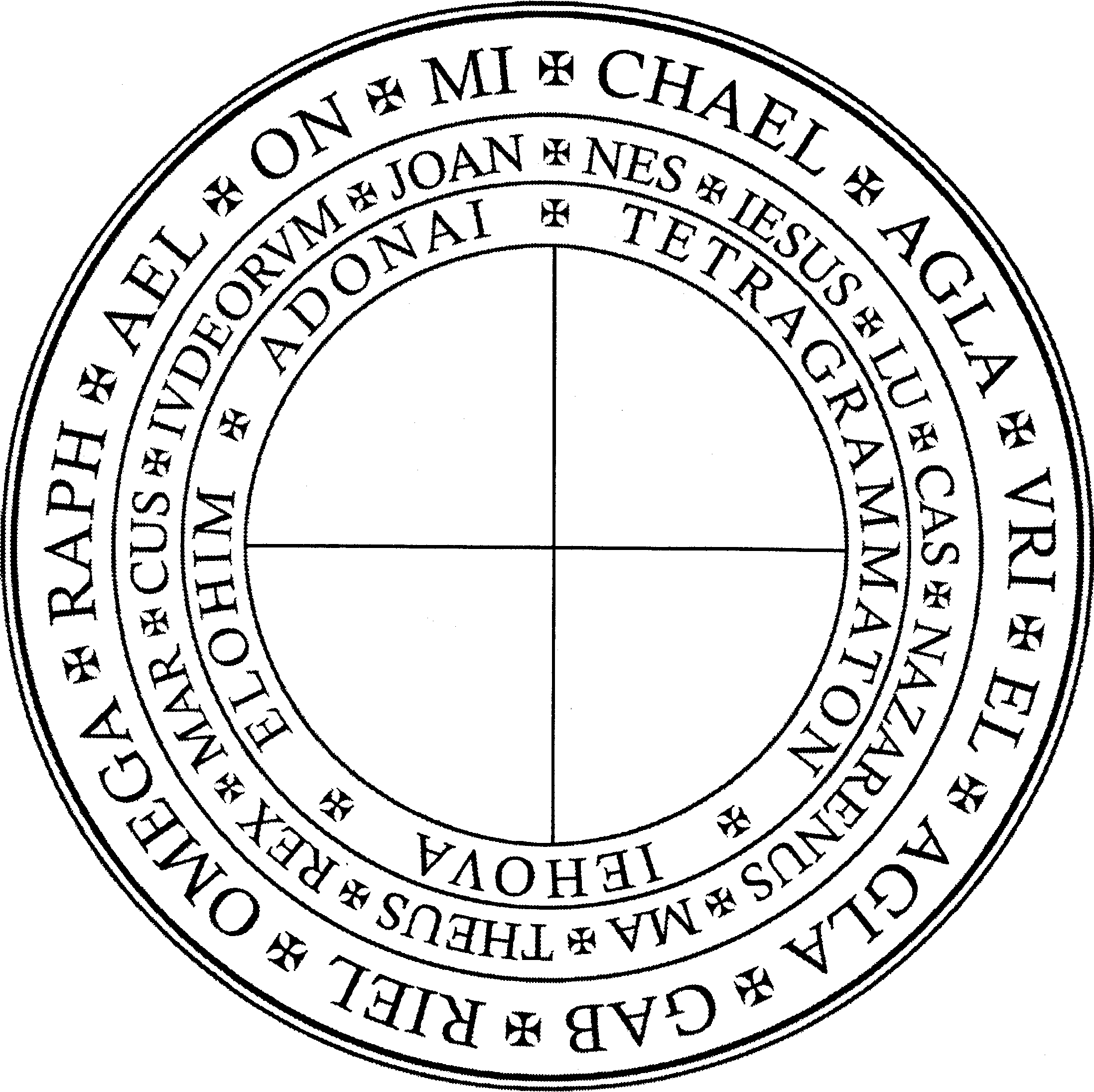

seems to be for protection: "It is," the author of the Tuba Veneris says "just as a very strong fortress, in order to protect themselves from the snares if the Daemons." The circle is usually inscribed with names and words of power and this particular example contains three bands with the following words derived from Judea-Christian religious/magical formulae:

+Mi+chael+AGLA+Uri+el+ALPHA+ Gabriel+OMEGA+Raph+ael+ON

+Joan+nes+JESUS+Lu +case+NAZ+RENUS +Ma+thew+REX+Mar+cus+JUDEORUM (“Jesus if Nazareth, King if the Jews')

+TETRAGRAMMATON +JEHOVA+ELOHIM+ADONAY

The circle is divided into four quarters, its fourfold nature reflected in the use of the names of the four angels of the cardinal points and the four evangelists. Interestingly, the order of the names to the cardinal points does not correspond to the order given in Agrippa or other sources with which I am familiar. For example, proceeding clockwise from the north, Grosschedel's Magical Calendar gives the orders Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, Michael for the angels and the Matthew, Mark, Luke and John for the evangelists.35 It seems as though the names attributed to the south and west have been exchanged for some reason. It seems unlikely, given his obvious learning, but one explanation for this is that perhaps the author was unconcerned with the symbolic relationship between names and directions, but solely sought to use them to strengthen his circle.

Many of the ingredients used by the author can be traced back to the work of Agrippa, or further back to 13th century Liber Juratus. The fumigation contains elements all found in book I, chapter xxvm of Occult Philosophy, in which Agrippa lists the stones, plants and animals under the power of Venus. The dove, a feather of which is used to write the Liber Spirtiuum, is associated with Venus in Agrippa's table of correspondences for the number sevens Once more the vitriolic water is used, both to write the book and to consecrate itV

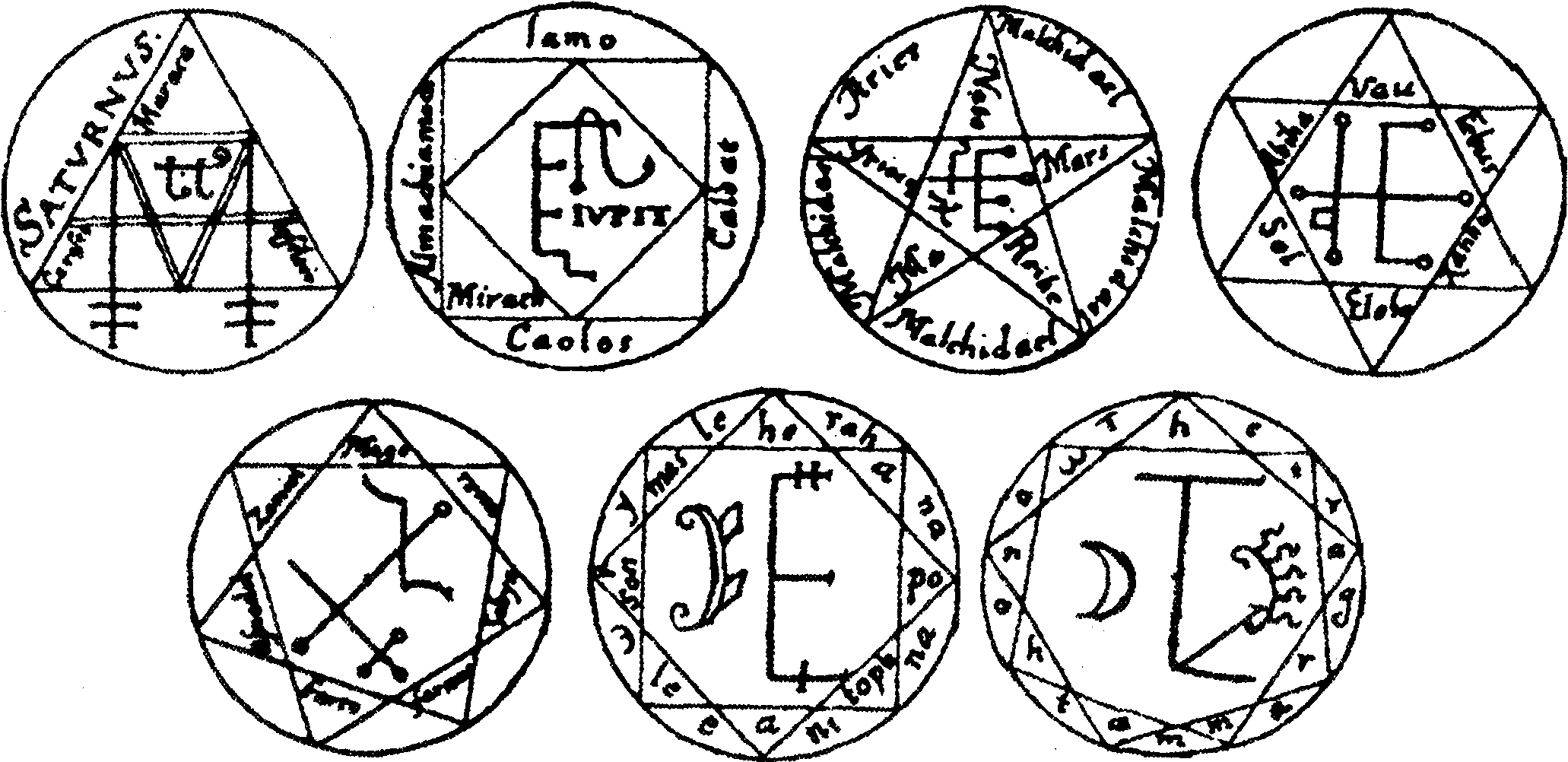

It seems probable that one the sources the author consulted was some variant on Grosschedel's Magical Calendar, if not the version published by Theodorus de Bry in 1620. The Calendar is a synthesis of Agrippa's magical correspondences and material from Paracelsus, pseudo-Agrippa and other sources presumably from manuscripts contemporary with those authors. It presents a set of seven very interesting seals relating to the planets, which seem to increase in complexity as they progress from Saturn to Luna.

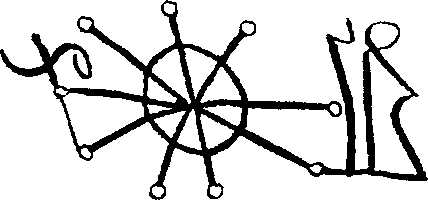

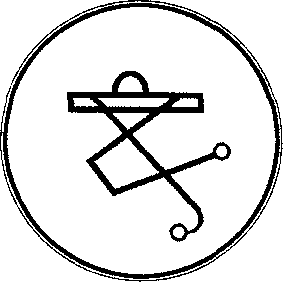

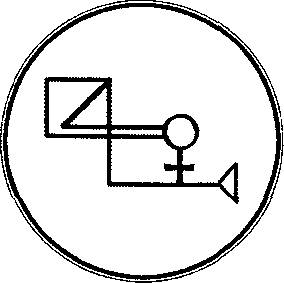

Fig. 1. Planetary seals from the Grosschedel' s Magical Calendar ( 1620)38

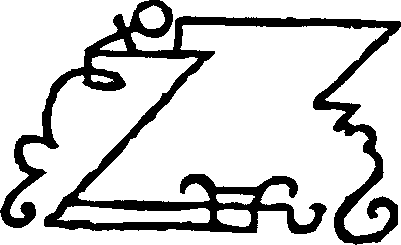

The Seal of Venus prescribed by the 'Tuba Veneris contains a version of the sigil enclosed in the heptagon above, along with the sign of the angel Anael. This sign of Anael would have been well-known to practitioners of magic throughout Europe. It is most famously described in the Heptameron, a text of ritual magic attributed to the 13th century scholar Peter d'Abano, but which was most likely composed no earlier than the cusp of the 15th and 16th centuries. By 1600 it was certainly circulating alongside the pseudo-Agrippa's FourthBook.39 Ultimately these angelic sigils can be traced back to Medieval texts such as Liber Juratus and the Manual ifAstralMagicVe As an aside it may be worth noting that the Liber Juratus seemingly refers to the sign as being that of all the Venereal angels, rather than specifically belonging to Anael.

eA.nail. I I

^ Jagz;n.

Fig. 2. The sigil and signs of the angel of Venus, from Turner's translation of the Heptameron ( 1654)4

The Seal of Venus also contains signs described by the Magical Calendar as 'characters if the planets'. These characters have their genesis in the art of Geomancy-a type of divination greatly respected by the authorities we have been discussing, who broadly considered it the 'sister' to, or terrestrial counterpart of, astrology^ This art involves the manipulation of 16 'figures', each composed of four lines of one or two dots-a system of binary divination in many ways superficially similar to the !-Ching.

The characters of Venus shown in the Magical Calendar correspond to the Geomantic signs of Puella and Amissio, and are imprinted on the Seal of Venus, along with a third character undoubtedly also ofGeomantic origin. This character may be a miscopied version of Amissio, missing the upper dot, or it may indicate the Geomantic sign, of Conjunctio, which was usually attributed to Mercury although the suggestion of a Venereal quality is obvious from its name! However, the latter theory seems doubtful at present: the lists of planetary characters from Geomantic sources of which I am aware do not have any sigils for Conjunctio that display this form. Additionally instances of the character relating to Amissio being miscopied in such a way are not unknown, for example The Key if Solomon preserved in Lansdowne 1203 misses the dot above the main body of the character.43

Amissio

Puella

Xand x

Y ’nd t

Conjunctio

Possibly

Fig" 3" Geomantic signs relating to Venus and their symbolic renderings.

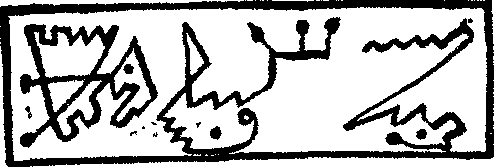

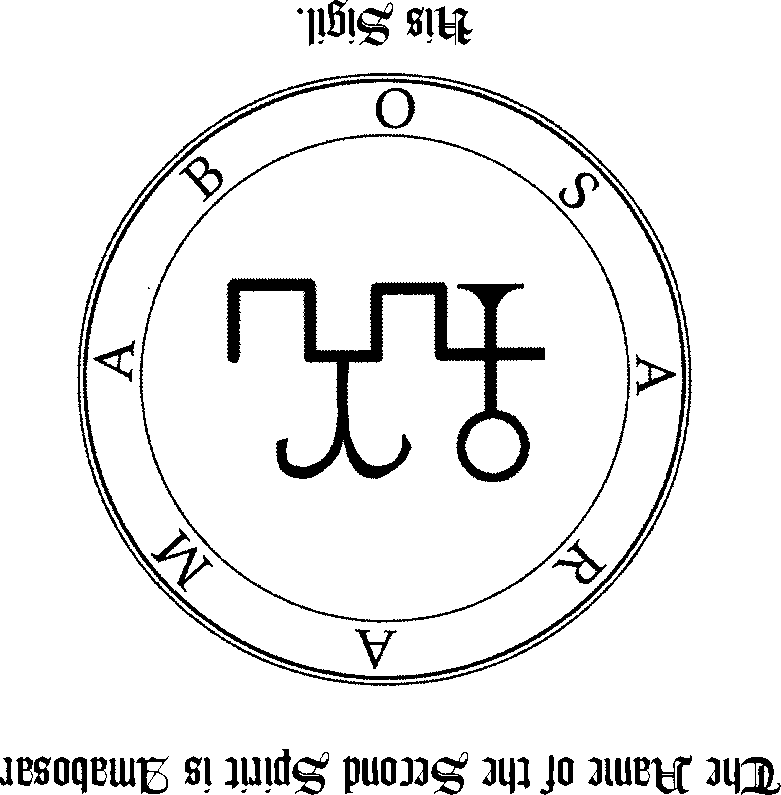

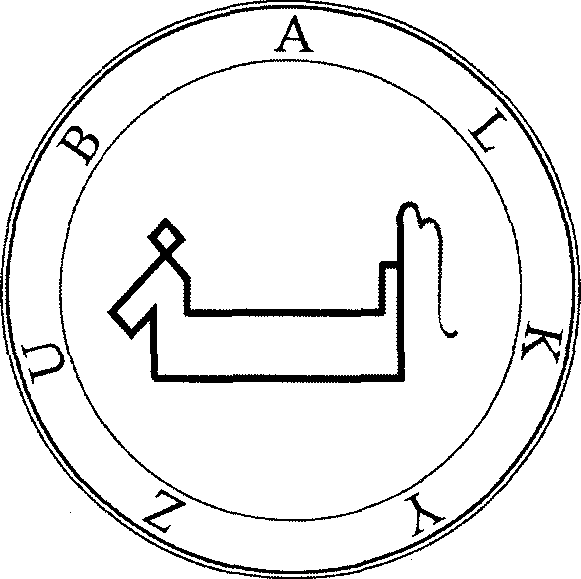

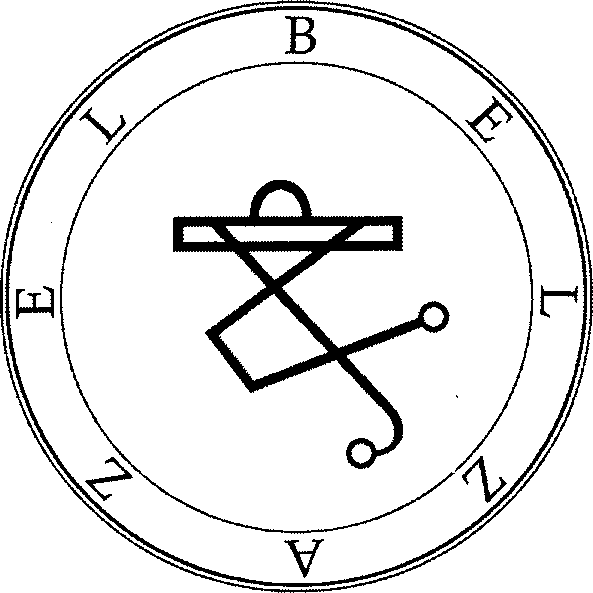

The Geomantic signs also find their way into the sigils of the six daemons, along with the other elements that make up the Seal of Venus, such as the astrological symbols for Venus and her related constellations Taurus and Libra. The key elements in the daemonic sigils are here briefly tabulated:

Daemonic A Sigil Mogarip Amabosar |

Core Elements Venus Venus & ambiguous Geomantic character |

Alkyzub Belzazel |

Amissw Libra |

Falkaroth |

Venus |

Mephgazub |

Taurus and Venus |

Fig 4. Core elements of the daemonic sigils.

Chthonic Powers and Steganographic Daemonology

While we are touching on the subject of the daemons it may be useful to look more closely ■ at their natures as indicated by the text. There can be no doubt that these are not planetary daemons, but rather are the inhabitants of the underworld regions which the goddess figure had such a deep connection in her nocturnal and fertility aspects. Once more, the connection is made clear from the initial verses, which mention an 'infternal dweller’ being subjugated by the sound of the horn. The author also refers to the magical doctrine that:

"... the good angels have been placed over the evil spirits by God Thrice-Greatest and Best so that they should rule over them; on account of which when something is commanded by a good Spirit to a bad one,

the former orders and calls the latter by means of his own capable invocation, and this perhaps may be in a language not particular to us mortals, or even comprehensible to us."

This interesting dualistic relationship between daemon and angel goes back to the very roots of the grimoire tradition, being found amongst the sources that make up the ancient Testament of Solomon (frst to third century AD). In the Testament, the demons that spread disease can often be exorcised by the invocation of their corresponding angel. The Tuba Veneris confirms that these daemons are 'evil', and although it assures the reader that the techniques for calling them are safe unless abused, this does not seem like the kind of magic that Dee, with his pious thirst for divine knowledge, would have pursued.

One of the most enigmatic aspects of the text are the conjurations that accompany the daemonic sigils. These are strings of what have become known as 'barbarous' words-inscrutable formulae that may simply be nonsense or may once have been words in foreign languages. There are none of the familiar formulae of Judea-Christian magic in these conjurations. Perhaps this is the 'language not particular to us mortals, or even comprehensible to us,' which the author mentions in his preface-the tongue of the spirits. Dee was, of course, notorious for his work with angels and the codification of the 'Enochian' language; perhaps this is being alluded to by our author. The conjurations may otherwise be in a magical language derived by similar visionary means ... or they may simply be 'gibberish'.

That is not to say that 'gibberish' words cannot be as magical as well worn foreign words or religious formulae. Aquinas

discusses his belief that all the apparatus of magic, such as signs, pentacles and words can only work through being beheld by some intelligent entity. Which is to say that signs and words have no inherent power, rather their meanings are agreed by the parties involved, who act on them accordingly.44 If such a position was considered then even the most obscure words and signs may be considered compacts between the magician and other entities.

There is, however, also the possibility that the conjurations are a cipher-an example of Steganographia, or 'Hidden Writing', an area in which Dee was also particularly interested, and the study of which went in and out of vogue during the course of the Renaissance.

There are some parallels that may be drawn between the 'Tuba Veneris and Trithemius' Steganographia-a work which Dee went to great lengths to procure, succeeding in 1562. Both works use invocations consisting of seemingly made-up words. Also, the works, give little indication of the particular talents allocated to each spirit, instead speaking about them in general terms. The 'Tuba Veneris tells us that the spirits are useful in the following ways:

" ... for the finding of hidden treasures, for journeys, for Business, for Navigation at sea, for war, and for similar things which the Spirits are able to do for you and be of service to you."

Trithemius applies his Steganographic 'spirits' (or modes of ciphering secret messages) to similar situations. For example: a prince planning the overthrow a city uses Steganographic methods in order to securely share his plans; a discoverer of treasure wishes to notify trustworthy friends to help him remove it so he sends a ciphered message, and so on“

However, attempts to apply the cryptographic techniques of both Trithemius' Steganographia and his Polygraphia to the mysterious conjurations in the 'Tuba Veneris have so far been unsuccessful! If the conjurations are not examples of cryptography, then it is possible that they may have been derived by some kind of mechanical method for purely magical purposes. An example of such a technique would be a table of words or letters that creates permutations of a single magical word or name (as detailed in the various Cabalistic tables for discovering the names of astrological spirits in Agrippa's Occult Philosophy), or perhaps even something akin the complex letter squares used by Dee and Kelly to dictate the Enochian language!

It seems there is some kind of structure to the language of the 'Tuba Veneris. The words used all have between two and four syllables, with certain syllables occurring frequently. For example, . a signifcant number of words begin with;1l' or ’Ham', have 'ga' for their central syllable or terminate with 'roth' or 'zoth'. It's tantalising to speculate that there must be some system behind these words, although exactly how it works still remains obscure.

There is also a curious relationship between the number of syllables in each conjuration, tabulated here, which may provide some further clue to the inner workings of the grimoire:

Spirit Syllable Count

Amabosar41

Belzazel42

Alkyzub44

Falkaroth45

Mephgazub46

Mogarip47

Fig, 5. Syllabic count for each conjuration.

Possibly the above does indicate a numerological or cryptographic mystery here to be solved-or perhaps these words are indeed "notparticular to us mortals".

Subsequent Influence: The German 'Tradition

It seems likely that the Tuba Veneris was composed in Germany, or at least enjoyed an enthusiastic reception there. Not only do several of the extant manuscripts belong to German institutions and have their provenance from German collections, but there is also a group of grimoires that seem to ultimately derive from the work.

These texts fall into what has become known as the 'Faustian' school of grimoire literature. Works of this genre are generally characterised by an unforgiving bloody fixation upon all things demonic. Although similarly bloodthirsty rituals are found in earlier texts of Medieval magic, the Faust-books rose to the level of popular and titillating literature in Germany being especially prevalent throughout the 18th century^ It is no surprise that when a German version of Tuba Veneris came into print for the first time it was in late 18th century Germany/9

Several German works relating to the Tuba Veneris can be found in the great 19th century compilations of printed works assembled by Horst and Scheible, along with other examples in manuscript form. Both Scheible and Horst preserve several works of interest attributed to Josef Anton Herpentil, variously described as a philosopher or a Jesuit.

The texts discussed here are difficult to date, especially in relation to the Tuba Veneris, although one is naturally suspicious the dates assigned to them by their printers and copyists. Generally these dates fall within the first half of the sixteenth century but appear to be spurious. For example: several Herpentil texts claim him as a Jesuit, although their alleged dates of composition invariably fall before the 1534 formation of the Society of Jesus!5'1 The Handwarterbuch des deutschen aberglaubens, an epic catalogue of Germanic lore, contains an article by Jacoby that dates the works ofHerpentil to end of the 17th century, or early 18th century/i

Amongst the literature attributed to Herpentil, it is the Inbegrifder Ubernatirlichen Magie that is of most interest. The Inbegrif.fseems to preserve more of the Tuba Veneris material than any of the other grimoires that will be discussed here, incorporating as it does all of the conjurations of the spirits into its text.

The Inbegrif.fdetails a ritual to conjure the three 'great princes', namely: Almischak, Aschirika and Amabosar/2 Amabosar is, of course, one of pseudo-Dee's spirits, although the derivation of the other two names is as yet obscure.

Herpentil's 'divine magic' owes a lot to the Tuba Veneris in its method. The circle is similarly made from paper, although in this instance the words are inscribed with the blood of a white pigeon. The author also stresses the need to retire to an undisturbed place where the conjuror will withdraw with his circle and a wand inscribed with the . seal of the spirit in weasel blood. The planetary seal also occurs, but has been transformed into the golden Seal of Jupiter, the names of whose angels are

Libellus Veneri Nigro Sacer vel Tuba Veneris.

written upon it in the blood of a white dove. In keeping with the ritual of pseudo-Dee, this seal must be laid upon any money that the spirits bring to the operator and there is also mention of applying heat to coerce obstinate spirits.

As previously mentioned, the conjurations of the Inbegzff incorporate all of those from the 'Tuba Veneris. They occur in order, although they have been merged together to give one conjuration for each prince:

Inbegrifder Ubernatiirlichen Magie Tuba Veneris

Almischak Aschirika Amabosar

Mogarip, Amabosar, Alkyzub Falkaroth, Belzazel Mephgazub

Fig. 6. The spirits of Herpentil and their corresponding conjurations in the Tuba Veneris.

While the dismissal of the spirit is also the same as in the 'Tuba Veneris, none of the subtleties that mark the author of the 'Tuba Veneris out as a man of sensitivity and learning are present in this or the other texts here mentioned. They are generally, save for the introduction, workmanlike and lacking in those elements that make the work ofpseudo-Dee so unique. Even their introductions, usually providing us with a fanciful lineage for the art, with obligatory mentions of Egypt and the Middle East, are poorly executed mystical cliches compared to the Tuba Veneris and its pleasing attempts to pass itself off as the work of Dee in addition to its powerful verse and imagery.

There is a related work that seems to draw on both the Herpentil text discussed above and also the same author's Liber Spiriiuum Potentis. The work in question is Compendium

[xlii]

Magiae Innaturalis Nigrae, attributed to the famous alchemist Michael Scot and dated 1255.53

Two ofHerpentil's spirits remain in the hierarchy discussed by Scot: Amabosar and Almischack, although their names have been corrupted to Almuchabosar and Almisch. Once again, the sigils provided for the spirits are different and in this case so are the conjurations. However, many aspects of the ritual are similar: the magus carries the wand, inscribed with blood (although of a white dove in this case), while an ornately decorated mitre and belt have been borrowed from the Liber Spirituum, Potentis.

Finally, there is a very short work entitled Magia Ordinis, attributed to one Johannes Kornreutheri (Johann Kornritter), an Augustinian Prior. This work, like the Compendium., is also linked to Herpentil's Liber Spirituum Potentis in its use of the circle, staff and mitre-again liberally scrawled upon with animal blood. The date of authorship is allegedly 1515, although the entry for the manuscript version held by the Wellcome Institute dates it to the early 18th century. 54 Of the fve spirits dealt with in Magia Ordinis, two have curiously familiar names: Azabhsar (Amabosar) and Mebhazzubb (Mephgazub).

Once again the ritual has aspects that ultimately relate to the 'Tuba Veneris, via Herpentil. The circle of paper and retirement to an undisturbed place are key elements, along with the taboo on talking during the ritual and use of heat to compel the spirits/5

Further connections between the texts under discussion can be drawn. Each text has a preface to the reader allegedly from

[xliii]

the pen of the pseudonymous author. Intriguingly as with the Tuba Veneris, the work of pseudo-Scot addresses the readers as Amatowbus Artis Magicae. All the texts make a connection between the practice of magical conjuration and the occult arts of the Middle East and furthermore, the Herpentil text perhaps alludes to its primary source as the Tuba Veneris by describing the magic under discussion as 'an English science'.

Since Amabosar is common to all of the works discussed above, a comparison between the seals and conjurations of the spirit is here provided:

Inbegrijf der

Tuba Veneris Ubernatirlichen Magie

Samanthos Garanlim Algaphonteos zapgaton chacfat Mergaym Hagai Zerastam Aleas Satti lastarmiz fiasgar loschemur karsila storichet krosutokim Abidalla guscharak melosopf/6

Amabosar! Amabosar!

Amabosar! Pharynthos Egayroth Melustaton Castotis Mugos Nachrim Amabosar!

Amabosar! Amabosar!

Compendium Magiae Innaturalis Nigrae

Asip Hecon Antiakarapasta Kylimm Almuchabzar Alget Zorionoso Amilek Amias Segor Almutubele Halli Merantantup Apalkapkor Imat Avericha alenzoth Elgab zai hazam Erasin Aresatos Astarkarapata Rilimm O Almuchabzar Kilim.

Magia Ordinis"

Kederesgh wehrelet dachimetigh Kebhdo Lafis deh Sewis nelim kigim tischengina denur Bauwordas menigh nibhind munedh maminegh Terowogh Konwad derli gentegh Kaswondh.

Fig.7. Comparison of the seals and invocations of Amabosar.

As noted above, the presence of these spirits in these documents indicates a possible German provenance for the Tuba Veneris. Along with the 18th century German edition of the text, two of the three manuscripts of the Tuba Veneris belong to libraries in Germany-the Universitatsbibliothek Erlangen-Nurnberg and the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

Conclusion

Through this examination of the sources of the Tuba Veneris we may conclude that the author was a keen student of the type of magic advocated by Agrippa, and that he had diligently studied the Three Books if Occult Philosophy, constructing a practical grimoire from the theoretical discussions of magic contained therein. The work, with its Classical allusions

and Neoplatonic and Pythagorean bias represents the apex of the grimoire genre, certainly in terms of the artistry and historical awareness of the author. The attempts at Sapphic verse, regardless of prosodic errors, also indicate an affinity with the Classical world and the workings of a sensitive and poetic mind, especially when compared to the unsophisticated conjurations found in most grimoires of the period.

However, it appears that this style of grimoire was an evolutionary dead-end. The works that were derivative of it lacked any of the charm and awareness that make it such an intriguing and enigmatic text. Instead the German grimoire-makers dragged the ritual through new and bloodier underworlds, hauling the spirits from their pagan Hades into a very Christian Hell. By the time Scheible published his epic Doctor Johann Faust’sMagia Naturalis et Innaturalis even Anael, 'great prince of Heaven', had been assimilated into the infernal hordes of Faustian magick The Faustian author describes him as the "fif-h lord of Hell and under the power if the angel Haniel" while the accompanying plate depicts the fallen one as a hunch-backed, red-eyed, ape like demon in fine clothes. From the trousers of these protrudes a conspicuously erect tail as he tugs on the cloak of a woman walking in front of him. Of course, like other classically inclined authors of the time, the author was well aware that he is living in the Christian era, and the pagan goddess is redefned as a planetary image of Venus, in line with the prevalent cosmological and astrological doctrines of the period. I conclude that the author was a Christian who saw nothing wrong with using knowledge that, since it originated from respected 'virtuous pagan' authors,

could be seen as being compatible with Christian doctrines.

The piety of the author, however, may be called into question by his designation of the text as a work of the 'Black Art' or 'Negromancy'. He mentions three divisions of magical art, namely: 'Magic, Kabbala, and Negromancy'. I would suggest that this indicates the main streams into which the art of magic is divided. First there is the natural magic, which also encompasses astrological and talismanic works. Second is the magical theology of Kabbala. Therefore by 'negromancy' he intends to indicate all magic that involves the conjuration of spirits. To this end he makes it clear that in spite of the text dealing with stygian daemons, he is presenting a true work of magic that can be practiced without risking ruin in this world or perdition in the next. This is as opposed to the base works of magic that lead men into diabolic pacts and are rightly proscribed by the church. We also find this curious categorisation in the later German works. Herpentil, for example, refers to his art as 'Black Magic,' but insists that it is a divine and holy science/'9 Perhaps the implication is that such magic is 'black' in so far as it relates to the nocturnal conjurations of subterranean daemons, and yet 'holy' in that it operates through the aid of divine and celestial agencies, such as the angel Anael.

From the influence on the Herpentil, Kornritter and pseudoScot, all German publications, along with the geographical distribution of extant Tuba Veneris manuscripts, it may be speculated that the author was based in Germany and may have had an awareness of the Hermetic works being published by the Palatinate house of Theodorus de Bry, or at least had

access to one of the sources used for the Magical Calendar. This would place the composition of the 'Iuba Veneris to circa 1620, that is, after De Brys publication of Grosschedel's Magical Calendar-. It is this work that contains the seven planetary seals the provenance of which are otherwise-at the time of writing-obscure.

Regardless of the exact location of the author in time and space the 'Iuba Veneris provides us with a perfect example of how the theoretical elements of Renaissance magic, such as those discussed in Agrippa's treatise, may have been put into practice by an enterprising magician. Despite being a work of considerable brevity, I know of no other ritual magic text that employs the systems of occult philosophy and planetary correspondence that flowered in the wake of Agrippa so methodically and thoughtfully. On a practical level it is as if the author has provided us with a template or textbook example after which we may also compose our own planetary rituals: the Scythe of Saturn and Sceptre of the Phoebus almost demand such an interpretation.

In conclusion, the 'Iuba Veneris is truly a gift to all the lovers of the magical art.

Philip Legard March 31, 2010 Leeds, United Kingdom

[XLIX]

Bibliography

Abognazar. The Veritable Clavicles if Solomon. Edited by Joseph Peterson. Esoteric Archives, 2001. http:/ /www.esotericarchives.com/solomon/ l1203.htm

Agrippa von Nettesheim, H. C. Three Books if Occult Philosophy. Translated by IE Edited by Donald Tyson. St. Paul, Minn: Llewellyn Publications, 1998.

---. Fourth Book if Occult Philosophy. Translated by Robert Turner. London: John Harrison, 1655.

Apuleius, Lucius. The Golden Ass. Translated by William Adlington. Edited by Martin Guy. Ames, Iowa: Eserver.org, 1996. http://books.eserver.org/ fiction/ apuleius/

Aquinas, Thomas. Contra Gentiles, Book III. Translated by Vernon J. Bourke. New York: Hanover House, 1957. http:! /www.josephkenny.joyeurs.com/ CDtexts/ContraGentiles.htm

Aristotle. Metaphysics. Translated by WD. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924. http:/ I classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/metaphysics. l.i.html

Betz, Hans Dieter, ed. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation: Including the Demiotic Spells. London: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Bruno, Giordano. "De Imaginum Compositione, Liber I," in Jordani Bruni Nolani Opera Latine Conscripta, Vol. II, Part III. Edited by F. Tocco and H. Vitelli. Florence: Le Monnier, 1889. http:/ /www.archive.org/stream/ jordanibruninol05brungoog

Burns, Terri. "The Little Book of Black Venus and the Three-Fold Transformation of Hermetic Astrology." Journal if the Western Mystery Tradition 12, 2007. http:/ /www.jwmt.org/v2nl2/dee_hermetic.html

Calder, I.R.F. "John Dee Studied as an English Neo-Platonist." PhD dissertation, London: The Warburg Institute, London University, 1952. http:/ /www.johndee.org/calder/html/TOC.html

Cattan, Christopher. The Geomancie ifMaister Christopher Cattan. Translated out if French into our English tongue. London: John Wolfe, 1591.

Dee, John. Mathematical Praeface to the Elements if Geometrie if Euclid if Megara. Translated by H. Billingsley. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing, n.d.

---a A Letter Containing a most briefe Discourse Apologeticall. Edited by Joseph Peterson. Esoteric Archives, 1999a. http:/ /www.esotericarchives. com/ dee/ aletter.htm

---. Tuba Veneris. Edited by Joseph Peterson. Esoteric Archives, 1999b. http:/ /www.esotericarchives.com/ dee/tubaven.htm

Foxe, John. Actes and Monuments if these latter and perilous dayes touching matters if the Church. London: John Day, 1563.

French, Peter. John Dee: The World of an Elizabethan Magus. London: Routledge, 1984.

[l]

Guthrie, Kenneth. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library. Grand Rapids, Missouri: Phanes Press, 1987.

Horst, George Conrad. Zauber-Bibliothek, Vols. I & II. Mainz: Florian Kupserbert, 1821.

Kieckhefer, Richard. Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer's Manual ifthe Fifteenth Century. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1997.

Klutstein, Iliana. Marsilio Ficino et la Theologie Ancienne: Oracles Chaldaiques, Hymnes Orphiques, Hymnes de Proclus. Florence: Olschki, 1987.

Kornritter, Johannes. Magia Ordinis. Translated by Phil Legard. 2007. http://www.larkfall.co.uk/blog/magia-ordinis.pdf

Mathers, Samuel Liddell MacGregor. The Key if Solomon the King. Revised by Joseph Peterson. Esoteric Archives, 2005. http:! I esotericarchives.com/ solomon/ksol.htm

McLean, Adam. The Magical Calendar. Grand Rapids, Missouri: Phanes Press, 1994.

---. "Database of Alchemical Manuscripts - Wellcome Institute." The Alchemy Website, 1995. http:! /www.levity.com/alchemy/almss8.html

Meyer, Marvin and Smith, Richard. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts if Ritual Power Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Naumann, Robert. "Ein Hollenzwang von 1555." Serapeum V5. Leipzig, TO. Weigel, 1844.

Pausanias. Description if Greece. Translated by WH.S. Jones and H.A.

Ormerod. London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1918.

Peterson, Joseph, ed. The Magical Calendar (excerpts). Esoteric Archives, n.d. http:/ /www.esotericarchives.com/mc/index.html

[u]

---. E-mail message to the author, November 2007.

Scheible, Johann. Das Kloster III. Stuttgart: Verlag des Herausgebers, I846.

---. Doctor Johann Faust's Magia Natura/is et Innaturalis, II. Stuttgart: Verlag von I Scheible, I849.

Taylor, Thomas. The Hymns if Orpheus. London: T. Taylor, I792.

Thomas, Keith. Religion and the Decline ifMagic. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, I97I.

Trithemius, Johannes. Steganographia. Translated by Christopher Upton, edited by Adam McLean. Edinburgh: Magnum Opus Hermetic Sourceworks, I982.

---. PolygraphiaLibri Sex. Cologne: Ioannem Birckmannum & Wernerum Richwinum, I564.

Walker, D.P. Spiritual and DemonicMagicfrom Ficino to Campanella. Surrey, Great Britain: Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2000.

Yates, Frances. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. London: Routledge Classics, 2001.

[ LIII ]

End Notes

-

1 The chief manuscripts in question being: London, the Warburg Institute. Warburg Ms. FBH 510; Erlangen, Universitatsbibliothek Erlangen-Ntirnberg. Ms. 854; Munchen, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. let. 27005. (Peterson 1999, Burns 2007)

-

2 In this regard see also Michael A. Putman's introductory notes for a summation of 1 org M. Maier's conclusions about the work.

S Foxe (1563), p.1445.

-

4 Dee 1570.

-

5 Dee 1599.

-

6 Calder (1952), chapter X.

-

7 An alternative hypothesis is that it could be written by a detractor seeking to connect Dee with diabolic arts in the mind of his readers. Although it would seem unlikely that someone seeking to defame Dee in such a way would create such a complex work.

-

8 See Betz (1996), Meyer and Smith (1999).

-

9 For example: The Heptameron, attributed to Peter d'Abano and the Fourth Book of Agrippa.

-

10 For Dee and treasure hunting, see Chalder (1952), chapter IX. For a general account of the treasure hunting mania in England, see Thomas (1971), pp.2S4-7.

-

11 For Agrippa's set of planetary images, see Agrippa (1651) II.xxxvii-xliv.

-

12 Agrippa (1651), Il.xlii.

-

13 For an example of this in translation see Taylor (1792), Hymn 55. The sixteenth century Latin translation in Klutstein (1987) renders the epithet in question as amatrix nocturnarum vigiliarum-lover of the nocturnal watches.

-

14 Pausanias, 8.6.5

-

15 Apuleius,XI.47

-

16 Ibid.

-

17 Regarding the particulars of his initiation,Lucius writes: "I approached neere unto Hell, even to the gates of Proserpina, and after that, I was ravished throughout all the Element, I returned to my proper place: About midnight I saw the Sun shine, I saw likewise the gods celestiall and gods infernall, before whom I presented my selfe, and worshipped them:" Apuleius, XI.48.

-

18 Apuleius,XI.47

-

19 For an overview of Ficino and Orphic singing, see Walker (1958), chapter I, and also the more recent work of Angela Voss.

-

20 For an account of this, see Hesiod, Theogony, lines 185-195. Note also the previous quotation from Apuleius- "The Cyprians [call me] Venus." (Apuleius, XI.47)

-

21 Compare with the conjurations and orations'in Mathers ( 1889), for instance.

-

22 Agrippa(1651), II.xxi.

-

23 Aristotle, Metaphysics, part v.

-

24 For Theon of Smyrna's How Many Tetraktys are There? see Guthrie (1987).

-

25 This Magical Calendar was engraved by the studio of Theodorus de Bry, probably by the hand of Mathieu Merian. It has been suggested that De Bry may have had links with a Christian mystical sect called the Family of Love, and may also have had an association with Dee.

26 See Yates (1972), chapter VI.

27 For a description of the talismans see Turner (1654) p.49, and for their use in conjunction with the Liber Spirituum, ibid. pp.57-8.

28 Concerning the Liber Spirituum, Mathers ( 1889) writes: "Thou shouldest further make a book of virgin paper, and therein write the foregoing conjurations, and constrain the demons to swear upon the same book that they will come whenever they be called, and present themselves

before thee, whenever thou shalt wish to consult them. Afterwards thou canst cover this book with sacred sigils on a plate of silver, and therein write or engrave the holy pentacles. Thou mayest open this book either on Sundays or on Thursdays, rather at night than by day, and the spirits will come."

29 Kieckhefer (1997), pp. 8-10.

30 Agrippa (1651), I.xlviii.

31 Hesiod, Theogony, lines 185-195.

32 Taylor (1792)

33 Mathers (1889), II.vii.

34 Bruno ( 1591), XIII.

35 McLean (1994), pp.34-5.

36 Agrippa (1651), II.x. Presumably the association of the dove with the planet relates to the Classical notion that Venus' chariot was drawn by white doves.

37 I speculate that it was such an ink that the author of the Warburg manuscript used to colour the title page and also to shade the illustrations of the seal and horn of Venus. Given the caustic nature of the solution, working with parchment instead of paper would be a necessity.

38 McLean (1994), pp. 62-74.

39 Based on the dismissal of the Fourth Book as a forgery by Agrippa' s pupil Weyer in 1563 it had presumably been already circulating in manuscript for more than thirty years by 1600.

40 For the Manual of Astral Magic, see Kieckhefer, 1997

41 Turner (1654), p.99.

42 For example, Cattan (1591 ), a comprehensive and influential tract on geomancy composed in 1558 that describes the art as variously 'sister' and 'daughter' to astrology.

43 See the section entitled 'Caracteres de Venus' in Peterson (n.d.). Helpfully this also shows a comparison with the de Bry sigils.

44 Aquinas (1264), 3.105

45 Examples from Trithemius (n.d.), chapters V and XI.

46 Trithemius ( 1564), books III and IV provide substantial codebooks in for ciphering messages in 'barbarous language'. Perhaps such a codebook was used in the construction of the Tuba Veneris' language.

47 Agrippa (1651), III. Xxvii.

48 See Kieckhefer (1997) for an example of a Medieval work that has

similar demonic and bloodthirsty fascinations. However, even the more benign and professedly 'holy' rites were not above using animal brains and so forth in their preparations, for example the copious use of bird brains in the incense recipes of Liber Juratus.

49 Veneris nigro sacer Autoris John Dee 1794. Aus dem Lateinischen in deutscher Obersetzung. Formeln und Sigille zur Anrufung von Venusintelligenzen fur Liebeszauber und Erfolgsmagie.

50 See for example Herpentil's SchwarzeMagie, dated 1505, in Horst ( 1821), volume I.

51 Peterson (2007)

52 Schieble (1846), pp.626-633.

53 The Scot Compendium was published in Neumann ( 1855). The original pamphlet that Neumann used for his edition claims a publication date of 1555. Liber Spirituum Potentis is reprinted in Horst ( 1821), volume II under the title Herpentilis' SchwarzeMagie, although a more complete version is preserved in manuscript held by the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. For the Compendium itself, see Naumann (1855).

54 McLean, 1995.

-

55 For a translation and notes on this text, see Legard (2007).

-

56 Note the incorporation of the astrological sign of Venus into the seal in a similar manner to those to the Tuba Veneris. Also compare the first half of the conjuration with that of Mephgazub in the Tuba Veneris-. Samanthros Jaramtin Algaphonteos Zapgaton Osachfat Mergaim Hugal Zerastan Alcasatti.

-

57 Taken from an electronic copy of Magia Ordinis-unkown provenance (probably from F.W Lehmberg (ed.) ceremonial-magie I: 22 Hauptwerke mittelalterlicher Magie).

-

58 Scheible (1849), pp. 87-90

-

59 Scheible ( 1846), p.627

[LVI J

[lvii]

The Life of Doctor John Dee

ohn Dee and Edward Kelly claim to be mentioned together, having been so long associated in the same pursuits, and undergone so many strange vicissitudes in each other's society. Dee was altogether a wonderful man, and had he lived

in an age when folly and superstition were less rife, he would, with the same powers which he enjoyed, have left behind him a bright and enduring reputation. He was born in London, in the year 1527, and very early manifested a love for study. At the age of fifteen he was sent to Cambridge, and delighted so much in his books, that he passed regularly eighteen hours every day among them. Of the other six, he devoted four to sleep and two for refreshment. Such intense application did not injure his health, and could not fail to make him one of the first scholars of his time. Unfortunately, however, he quitted the mathematics and the pursuits of true philosophy to

indulge in the unprofitable reveries of the occult sciences. He studied alchymy, astrology, and magic, and thereby rendered himself obnoxious to the authorities at Cambridge. To avoid persecution, he was at last obliged to retire to the university of Lou vain; the rumours of sorcery that were current respecting him rendering his longer stay in England not altogether without danger. He found at Louvain many kindred spirits who had known Cornelius Agrippa while he resided among them, and by whom he was constantly entertained with the wondrous deeds of that great master of the hermetic mysteries. From their conversation he received much encouragement to continue the search for the philosopher's stone, which soon began to occupy nearly all his thoughts.

He did not long remain on the Continent, but returned to England in 1551, being at that time in the twenty-fourth year of his age. By the influence of his friend, Sir John Cheek, he was kindly received at the court of King Edward VI, and rewarded (it is difficult to say for what) with a pension of one hundred crowns. He continued for several years to practise in London as an astrologer; casting nativities, telling fortunes, and pointing out lucky and unlucky days. During the reign of Queen Mary he got into trouble, being suspected of heresy, and charged with attempting Mary's life by means of enchantments. He was tried for the latter offence, and acquitted; but was retained in prison on the former charge, and left to the tender mercies of Bishop Bonner. He had a very narrow escape from being burned in Smithfield, but he, somehow or other, contrived to persuade that fierce bigot that his orthodoxy was unimpeachable, and was set at liberty in 1555.

[lviii]

On the accession of Elizabeth, a brighter day dawned upon him. During her retirement at Woodstock, her servants appear to have consulted him as to the time of Mary's death, which Circumstance, no doubt, first gave rise to the serious charge for which he was brought to trial. They now came to consult him more openly as to the fortunes of their mistress; and Robert Dudley, the celebrated Earl of Leicester, was sent by command of the Queen herself to know the most auspicious day for her coronation. So great was the favour he enjoyed that, some years afterwards, Elizabeth condescended to pay him a visit at his house in Mortlake, to view his museum of curiosities, and, when he was ill, sent her own physician to attend upon him.

Astrology was the means whereby he lived, and he continued to practise it with great assiduity; but his heart was in alchymy. The philosopher's stone and the elixir of life haunted his daily thoughts and his nightly dreams. The Talmudic mysteries, which he had also deeply studied, impressed him with the belief, that he might hold converse with spirits and angels, and learn from them all the mysteries of the universe. Holding the same idea as the then obscure sect of the Rosicrucians, some of whom he had perhaps encountered in his travels in Germany, he imagined that, by means of the philosopher's stone, he could summon these kindly spirits at his will. By dint of continually brooding upon the subject, his imagination became so diseased, that he at last persuaded himself that an angel appeared to him, and promised to be his friend and companion as long as he lived. He relates that, one day, in November 1582, while he was engaged in fervent prayer, the window of his museum

[ LIX J

looking towards the west suddenly glowed with a dazzling light, in the midst of which, in all his glory, stood the great angel Uriel. Awe and wonder rendered him speechless; but the angel smiling graciously upon him, gave him a crystal, of a convex form, and told him that, whenever he wished to hold converse with the beings of another sphere, he had only to gaze intently upon it, and they would appear in the crystal and unveil to him all the secrets of futurity.* This saying, the angel disappeared. Dee found from experience of the crystal that it was necessary that all the faculties of the soul should be concentrated upon it, otherwise the spirits did not appear. He also found that he could never recollect the conversations he had with the angels. He therefore determined to communicate the secret to another person, who might converse with the spirits while he (Dee) sat in another part of the room, and took down in writing the revelations which they made.

He had at this time in his service, as his assistant, one Edward Kelly, who, like himself, was crazy upon the subject of the philosopher's stone. There was this difference, however, between them, that, while Dee was more of an enthusiast than an impostor, Kelly was more of an impostor than an enthusiast.

* The "crystal" alluded to appears to have been a black stone, or piece of polished coal. The following account of it is given in the Supplement to Granger's BiographicalHistory. "The black stone into which Dee used to call his spirits was in the collection of the Earls of Peterborough, from whence it came to Lady Elizabeth Germaine. It was next the property of the late Duke of Argyle, and is now Mr. Walpole's. It appears upon examination to be nothing more than a polished piece of cannel coal; but this is what Butler means when he says,

'Kelly did all his feats upon

The devil's looking-glass—a stone."'

In early life he was a notary, and had the misfortune to lose both his ears for forgery. This mutilation, degrading enough in any man, was destructive to a philosopher; Kelly, therefore, lest his wisdom should suffer in the world's opinion, wore a black skull-cap, which, fitting close to his head, and descending over both his cheeks, not only concealed his loss, but gave him a very solemn and oracular appearance. So well did he keep his secret, that even Dee, with whom he lived so many years, appears never to have discovered it. Kelly, with this character, was just the man to carry on any piece of roguery for his own advantage, or to nurture the delusions of his master for the same purpose. No sooner did Dee inform him of the visit he had received from the glorious Uriel, than Kelly expressed such a fervour of belief that Dee's heart glowed with delight. He set about consulting his crystal forthwith, and on the 2nd of December 1581, the spirits appeared, and held a very extraordinary discourse with Kelly, which Dee took down in writing. The curious reader may see this farrago of nonsense among the Harleian MSS. in the British Museum. The later consultations were published in a folio volume, in 1659, by Dr. Meric Casaubon, under the title of A True and Faithful Relation if what passed between Dr-. John Dee and some Spirits; tending, had it succeeded, to a general Alteration if most States and Kingdoms in the World."

* Lilly, the astrologer, in his Life written by himself, frequently tells of prophecies delivered by the angels in a manner similar to the angels of Dr. Dee. He says, "The prophecies were not given vocally by the angels, but by inspection of the crystal in types and figures, or by apparition the circular way; where, at some distance, the angels appear, representing by forms, shapes, and creatures what is demanded. It is very rare, yea, even

The fame of these wondrous colloquies soon spread over the country, and even reached the Continent. Dee, at the same time, pretended to be in possession of the elixir vitae, which he stated he had found among the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, in Somersetshire. People flocked from far and near to his house at Mortlake to have their nativities cast, in preference to visiting astrologers of less renown. They also longed to see a man who, according to his own account, would never die. Altogether, he carried on a very profitable trade, but spent so much in drugs and metals to work out some peculiar process of transmutation, that he never became rich.

About this time there came into England a wealthy polish nobleman, named Albert Laski, Count Palatine of Siradz. His object was principally, he said, to visit the court of Queen Elizabeth, the fame of whose glory and magnificence had reached him in distant Poland. Elizabeth received this flattering stranger with the most splendid hospitality, and appointed her favourite Leicester to show him all that was worth seeing in England. He visited all the curiosities of London and Westminster, and from thence proceeded to Oxford and Cambridge, that he might converse with some of the great scholars whose writings shed lustre upon the land of their birth. He was very much disappointed at not fnding Dr. Dee among them, and told the Earl of Leicester that he would not have gone to Oxford if he had known that Dee was not there. The Earl promised to introduce him to

in our days," quoth that wiseacre, "for any operator or master to hear the angels speak articulately: when they do speak, it is like the Irish, much in the throat!"

[LXII]