Geosophia: The Argo of Magic I - Jake Stratton-Kent 2010

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My profound gratitude to the following, in no particular order:

To generations of scholars, from Charles Wycliffe Goodwin to Hans Dieter Betz, who brought us the Greek Magical Papyri. To those modern academics, many named in the bibliography, who are examining Graeco-Roman magic in a new light. To Juliette Williams for asking a most leading question and supplying fabulous research materials. To Johnny Jakobsson and Erik de Pauw for sharing their passion for the grimoires; to Stephen Skinner and David Rankine for their prodigious researches into Solomonic magic and above all for raising awareness of its Hellenistic origins. To Brendan Hughes for providing essential hardware; to Dis and Erzebet Carr; to Joseph Peterson; to Michelle Newitt and Theresa Chisholm for their contributions to the Picatrix section and for many other things; to Peter and Alkistis for sharing the vision.

INTRODUCTION

What is Goetia?

Firstly, a word about what goetia is not. Many people with some acquaintance with occult literature will associate goetia with the first book of the Lemegeton, the Goetia of Solomon the King; which deservedly or not is nowadays perhaps the most famous of the grimoires. Indeed, in Aleister Crowley’s Book IV, all the references to goetia involve this grimoire and nothing else. However, this first book of the Lemegeton originates in mid-seventeenth century England, whereas the term goetia is ancient Greek, so clearly there is some distance between the date of the grimoire and the origins of goetia.

This significant distance is unconsidered in popular usage, and even among many modern authors. It is not uncommon to hear such expressions as goetic demons or even goetias when referring to the spirits of this grimoire; which could be acceptable were it applied equally to demons of other grimoires, which it is not. This restricted usage is inaccurate in other ways and one in particular is of interest here. In English, the word magician derives from magic, the person taking their name from their art. Two other words used for magician in Greek follow similar lines, phar-makos refers to the use of drugs, and epodos to the use of chants; only macros does not follow this rule, and that is a loan word from Persian, its relationship to magic being possibly perceived rather than actual. By contrast, the term goetia derives from a word indicating a person, a rare case of the art taking its name from the artist. Such a person was termed a goes. Goetia is related primarily to the identity of the operator, and only secondarily to their art or perceptions of it. Additionally the evocation of evil spirits’, while relevant to the original context of goetia, and central to

its later significance, does not define the operator’s principal role or the original purpose of their activities.

The word goes relates to terms describing the act of lamenting at funeral rites; the mournful howling considered as a magical voice. These magical tones can guide the deceased to the underworld, and raise the dead. This is the root of the long connection of goetia with necromancy, which has come to be termed black magic.

Authors from Cornelius Agrippa to Mathers and Waite use the term goetic of most of the grimoires, particularly the darker ones. The recent fame of the Goetia of Solomon has obscured the long association of the term with supposed black magic generally.

From Agrippa the negative associations of the word goetia go back beyond the medieval period into Classical antiquity. Therefore, it might appear feasible that goetia is a very old word for black magic. However, in Greek use magic was a term derived from a Persian root, whereas goetia originates within the Greek language. In the history of Western magic, not only did goetia come first, it possessed a character that distinguished it from many later forms. In its original form, goetia did not involve the same worldview or assumptions as later magic of the approved Juda?o-Christian type. The circumstances in which it competed unsuccessfully for a time are no longer applicable, and the old assumptions increasingly questioned. Unfortunately, since magic is a specialized, largely amateur pursuit in the West, the old cultural assumptions linger in many forms, with an occasional nod in the direction of the new.

Before postmodernism, the differences between goetia and mainstream Western magic involved certain cultural assumptions about what constitutes Western civilization and what constitutes primitive’ religion; including those ideas inherited by nineteenth century occultists. These notions have impeded clarity in the Western tradition of magic. In order to express this more clearly some of the old assumptions regarding Westernism require deconstruction, or at least to be identified. There were two main strands to the late modern view of Western civilization: the Judazo-Christian on the one hand and the Classical or Neo-Classical on the other; each with their subdivisions, alliances and differences. This

bipolar superstructure while overly simplistic is nevertheless useful in understanding Western magic. Of course, in reality Northern European cultures played a large role in the evolution of Western civilization, magic included, but so long as we recognize it as a generalization, this idea has some use even now. It is in this sense then that my direction in writing is more towards a deconstructed Classicism than a deconstruction of Judaso-Christian tradition.

The over emphasis on the Judaio-Christian elements in the grimoires has long obscured the immense contribution of the Graico-Roman or Hellenistic world to Western magic. Ancient Jewish and Christian traditions were but parts of this world. In this deconstruction of the old view of the Classical world, its importance to Western magic as a whole is reevaluated, not only in the past but also in the immediate present and into the future. To avoid misunderstanding, this is not a strictly academic approach, though availing itself of modern studies. The study of interpretations of history is termed historiography, and I avail myself of this term to indicate that interpretation to a definite end rather than strictly scientific use of literary and other evidence is the purpose here. Besides literary and archeological evidence, I also employ real geographical, ethnological and migratory foci. This is in order to deconstruct the old assumptions regarding the superiority of Greek over Pelasgian and other cultures which are equally a part of the Greek legacy. By means of this apparatus, I hope to elucidate and reinterpret Western magic and its relation to the wider world, both ancient and postmodern.

This approach serves a dual purpose, underlining the aspects of this lore most relevant to goetic magic, not only historically but also in contemporary practice. This, rather than a straightforward study of Greek religion, is the intent throughout. To accomplish this requires an interpretative method which necessarily differs in purpose and practice from impartial academic and archaeological evaluation of evidence. Traditional methods of philosophical speculation employed Greek myth as emblems of moral or cosmological truths; the approach here both follows and departs from this precedent. As will be further elucidated in our discussion of myth, the aspects of myth and history emphasized differ, as does the

practical purpose served. This purpose is neither impartial historical understanding nor a re-enactment style historical reconstruction nor even Hellenic neo-paganism. It serves an emergent synthesis of global magic produced by cultural forces active in our own time, in which Western magic is fused with influences from the New World and elsewhere. These Afro-Hispanic influences, essentially spiritist in nature, have strong affinities with earlier phases of Western magic. In order to facilitate the fusion to maximum effect, these earlier phases and their contributions to modern magic require elucidation.

The last great synthesis of magic occurred in the Hellenistic world; formulated in the great schools of Neoplatonism and Hermeticism, and incorporating astrology and the Grieco-Egyptian roots of alchemy. Major factors in these fusions were the older traditions of Chaldean star-lore and Greek goetia. Although modern occultists often imagine the roots of their tradition lie in the Kabbalah, this is in fact a medieval system that did not enter Western magic until the Renaissance: with Mirandola and Agrippa in the 1490s. Even then, Kabbalah, and in particular those parts of Kabbalah incorporated in modern magic, involve a good deal of earlier Hellenistic origin.

The Spheres of the Primum Mobile, fixed stars, the seven planets and the Earth were integral parts of the Neoplatonist astronomical model. Thus, the order of the planets corresponding to the sefirot of the Tree of Life essentially originates in Neoplatonism and Ptolemaic astrology. The connection of these categories with letters, names and numbers by modern ritual magicians, whether they follow Agrippa or the Golden Dawn, also derives directly from Neoplatonist pagan magicians. Nor is this a superficial resemblance; Neoplatonism is — after all - the origin of the Logos doctrine fundamental to Christian theology, and the deity without attributes central to that of the Kabbalists.

For the first time since the Hellenistic era, a new global magical synthesis has the potential to emerge. Given cultural conditions in the West and elsewhere, this potential will be realised. What needs to be asked is, what part will Western traditions play in it, and what aspects of Western magic are most compatible with New World and other magical traditions? In

order to answer these questions it is important to bear in mind that the Greeks were in prolonged contact with both African and Indian traditions, making Western a very ambivalent expression. Given the globalisation of modern culture and the importance of Afro-Hispanic traditions from the New World in modern magic, looking beyond the recent emphasis on Kabbalah in Western ceremonial magic is necessary to achieve a workable synthesis.

It is my contention that goetic magic, properly understood, is the most important fundamental element Western magic has to contribute to the melting pot, being most compatible with magical practices from the other cultures concerned. In order for this to take place, a major reappraisal of goetic magic is necessary. In the academic world, this has already occurred in large part, but it remains necessary among Western magicians and their contacts in the other traditions. Naturally, despite the usefulness of academic studies, the requirements for this are rather different. It is to these different requirements that my study is geared, and while this requires saying, it does not require an apology.

Chthonia Lost

Many authors have expended considerable energy distinguishing magic from religion, without much effect. In reality, magical rites often include remnants of religious traditions older than those currently in favour. As recollection of the original context recedes such survivals are either devalued and demonised or heavily disguised and redefined. Negative perceptions then replace the former prestige and power of the older tradition. Even after deconstructing unsympathetic interpretations, our perceptions can never be those of the original participants in these traditions in their various historical phases over many years. Therefore, while deconstructing an outworn historical view of myth is the method, the intent is a mythic view of history.

Franz Cumonf s book Chaldean Magic speaks of Persian magic entering Greek use around the time of the Persian Wars. He says that a Book of

Ostanes: was the origin of the magic substituted from that time forth for the coarse and ancient rites of Goetia, As can be seen from accounts of them in Herodotus, the rites of the Magi known to the Greeks seem in the main to have been pre-Zoroastrian, and no less coarse and ancient in many respects. More recent studies suggest that far from being replaced what we know as goetia took its historical form around this time, principally through the new movement known as Orphism. This was, as will be shown, a reform of more ancient chthonic elements in Greek religion, incorporating eastern ideas. Despite occasional use of the term magos these eastern influences were not Zoroastrian; they originated chiefly in Crete, Asia Minor and Chaldea, while at the same time Orphism retained much that was innately Greek.

In other words, this was actually more of a transfusion than a replacement; and in many ways revitalized and transformed ancient chthonic traditions; as Orphism actively concerned itself with Thracian and Pelasgian traditions, while introducing Eastern elements at the same time. The Book of Ostanes does not represent an entirely new current. In history, but not its preceding myth, goetia began rather than died out with the advent and evolution of these Magian rites. Many features of old Greek rituals underwent a major transformation around this time, as religion transformed from family and tribal cults to city cults; and it is precisely then that goetia appears.

In the past, understanding this transformation was complicated by a curious phenomenon in the history of magic, its foreign-ness whether actual or supposed. Goetia was foreign to the Greeks in several ways, in mythic terms it was associated with Dionysus in whom foreign-ness or outsider status was an intrinsic principle. This quality of the god was further reinforced by association with survivals of Pelasgian traditions and the cults of foreign deities such as Cybele. These were all essentially chthonic in nature. Outsider status is extremely frequently associated with demonic figures in religion, and it is remarkable that despite these associations Dionysus retained and even enhanced his divine status.

The chthonic realm was essentially coexistent with the celestial world in Greek religion; it only became demonised after the rise of more exclu

sive ouranian or celestial emphases in later religions. However, the difference in perspective and emphasis, and the association with foreign and lower class practices, contributed to making the goetic rites and traditions increasingly repugnant to the urban literati. This prejudice significantly assisted further subsequent demonisation, but at that time goetia was neither legislated against nor persecuted. It was an accepted part of the culture, that happened to be unpopular with intellectuals. The old idea that the chthonic and celestial emphases in Greek religion were the products of different cultures is flawed. In fact many of the chthonic deities and rites of Greek religion are every bit as Indo-European as the sky-god Zeus; additionally such a dualism already existed in Mesopotamian and Hittite cultures. The two worlds co-existed in perfect balance within Greek religion for thousands of years. The demonisation of the chthonic has comparatively little to do with matters of ethnicity; on the contrary foreign-ness is simply a common attribute of the demonic. Nevertheless, fertile ground for this demonisation was present in the Classical and Hellenistic eras, and indeed long before.

The dangerous nature of many chthonic figures is essential to recognise, although at the same time other roles are also proper to them. Hades, Persephone, Demeter and Hecate, along with Hermes Chthonios are significant figures in such traditions. Hecate is often associated with the negative stereotype of witchcraft, but also had very benign roles that preceded these associations. Demeter, along with Persephone and Hades (and his alter ego Plutos) were the pre-eminent deities of the Eleusian Mysteries; her cult began in prehistoric times. While associated with earthly fertility and with the Underworld, the constellation Virgo has long been associated with her; her nature is both celestial and chthonic. While Hades as King of the Underworld was at best an ambivalent character, his alter ego Plutos was the god of wealth through the fruits of the earth. Attempts to distinguish the two are erroneous. Earthly fertility was also the special province of Demeter and Persephone, with which they were as much concerned as with death. Alongside the enactment of Demeter’s search for Persephone after her abduction by Hades there appears to have existed another yet more mysterious rite, the fruitful marriage of Plutos

and Persephone. On the other hand, the dead were termed children of Demeter, or Demetrians. More sinister deities and entities, dangerous, requiring placating, were also strongly associated with the chthonic realm. These too had some positive roles, even if dependent on their dangerous nature; the Erinyes for example presided over oaths, with the clear implication of punishment for perjury. They avenged wrongdoing and, while terrible, their actions upheld what Greek culture considered right conduct. There are in fact few figures in Greek myth, if any, that are wholly evil in nature.

There were nevertheless major differences in the cults of deities of the Olympian or celestial realm and those of the chthonic region. Celestial deities are invoked in daylight, in a state of purity and cleanliness, often wearing white; the occasion is joyful, the altar is raised up, and the sacrificial victim looks towards the heavens at the moment of sacrifice. The dead on the other hand were honoured with lamentations, from the Greek word for which the term goetia has its origin. These ceremonies were generally nocturnal, as were the Hittite equivalents. The garments of the mourners were torn and defiled with dirt, their hair hung loose and in disarray. No altar was erected for the dead, rather a pit was dug, into which the sacrificial beast looked down. Many features of the cult of the dead were shared with chthonic deities and heroes. Some distinctions drawn between the rites of the two worlds in the past are not as binding as had been supposed; some sanctuaries and rites included elements and features associated with both chthonic and celestial entities.

The history of Greek religion is long and complex; its beginnings predate Homer by a far greater period than that from Homer to our own times. It is not the purpose of this work to give an account of this history, but its antiquity is important to bear in mind, as most of us are only familiar with the Classical period in some basic form. The origins of the Greek cults are to be found in the Neolithic period, from which originate substantial connections with the pre-literate cult iconography of Catal Huyuk. The Minoan and Mycenaean periods followed in the Bronze Age. After the destruction of these aristocratic cultures and their palace cults was a four hundred year Dark Age. This permitted a revival of

older Neolithic forms that had survived among the lower classes. Towards the end of this Dark Age, as well as during it, these were cross-fertilised with Middle Eastern influences from 1200 bce to 600. This influence originated in what is now modern Turkey and Northern Syria and was particularly strong in Cyprus, from which it was diffused to the larger Greek world. From the 26th dynasty around 660 bce Greek mercenaries served the Pharaoh, and influence from Egypt increased accordingly. The origins of much of Greek ritual and myth in the religions of the Hittites are important, but beyond the scope of a study tracing Greek influence on Western magic. The emphases for this study are the influences from Phrygia and the European near equivalent in Thrace; also considered are Chaldean ideas - often confused with Zoroastrian ideas in antiquity — such as Zurvanism and its forebears.

Chthonia Regained

Notwithstanding the complexity of the relations between celestial and chthonic religion, the goetic strand within western magic essentially represents survivals of more primal elements within host traditions of another character. For example, magical approaches adapted and systemised by the Neoplatonists. Invariably such brief attempts as have been made to define goetia are from the viewpoint of such host traditions or from viewpoints hostile to magic in general, rather than the viewpoint of goetia itself. It is difficult to speak of goetia in its own terms when competing with the accumulated assumptions of so many intervening centuries. For the last two thousand years, our civilisation has lived with the assumptions inherent in Revealed Religion. The civilisations of Classical Greece, and all other civilisations of the ancient world, were either built or superimposed upon a tradition of thousands of years of what is known as Natural Religion. Whereas Revealed Religion is delivered from on high by a revelation - frequently represented by a Book - Natural Religion is built up from below; the result of observation of and interaction with the visible world, including perceived supernatural or numinous forces. At the heart of these two approaches to religion are two entirely different worlds.

These two worlds, the centres of two opposed worldviews, can be termed the celestial and chthonic worlds. These are not the limits of the worldviews concerned, but their centres. That is to say, while Revealed Religion has as its base the celestial or even super-celestial realm, it does not exclude considerations of other regions, such as Earth, Hell and the physical universe in general. Similarly, while natural religion has the Earth and the Underworld at its heart, this does not prevent it dealing with gods of thunder or the Sun and Moon.

In the same way, the source of the revelation of revealed religion is celestial, and this is the centre of its worldview. By contrast, the chthonic realm was the source of oracular power at all stages of Greek religion. The celestial or transcendental realms became all important in later magic, not least as the source of the magician's authority. Previously the earth as source of life and the underworld as the abode of the dead were central to religion and magic. More to the point, much of the magic of later times - particularly that characterised as goetic - was an adaptation - one might even say a distortion — of the older type. Nevertheless, the initial transition from chthonic to celestial bases for magical authority did not involve a major change of character or content.

The roots of the word goetia exemplify its chthonic connections. Whereas goetia is commonly translated howling, following the precedent of nineteenth century authorities which are too often unquestioned, a closer translation would be wailing or lamenting. There is a large group of related words in Greek, the majority of which refer specifically to ancient funeral rites. The tone of voice used in these rituals distinguished the practitioner of goetia, and the concern with the Underworld was equally explicit.

The precursors and the earliest manifestation of goetia are principally concerned with the dead. At the same time, despite some parallels and later syncretism, it has little intrinsic connection with the aristocratic Olympian religion of Homer. Its primary role was benign in that it served a role in the community; that of ensuring the deceased received the proper rites to ensure they left the living alone. Alongside this were additional roles. These included laying ghosts, including those where proper burial

had not been possible. Such restless spirits were troublesome, even hostile and dangerous. Their existence was a major reason for the practice of funeral rites in the first place.

Another aspect of goetias involvement with the dead was necromancy. This, the art of divination by the dead, correlates naturally with the ability to guide the dead to the Underworld. Those who could guide souls to the Underworld could bring them back, at least temporarily. In its original religious context, necromancy was not perceived as anti-social, and some major necromantic oracular centres existed throughout the Greek world.

The most sinister aspect of this involvement with the dead was the ability to summon such spirits for purposes other than divination. Like necromantic divination, this is a natural consequence of the role of guide of souls. However, it also relates very closely to the ability to deal with hostile ghosts of various kinds. The arts of exorcism and evocation are intimately related. It is from this aspect of its past that goetia is associated with demonic evocation. Distinctions between underworld demons and the angry dead have always been vague. Additionally, expertise in rites concerning the dead necessarily involves the gods and guardians of the Underworld. Consequently, in various guises, raising spirits has been associated with goetia for much of its history,

The impression caused by the confusion between the Goetia of Solomon and goetia itself is that goetia concerns evocation alone. There is a stereotyped image of the conjurer calling up spirits into a triangle from within a circle, and bidding them to perform this, that and the other thing. This seemingly reduces all goetic operations to the same format, which is not the case at all. Even disregarding the religious and funerary aspects, goetia involves magical methods of every variety. It is true that goetic magic involves the participation of spirits in virtually all its operations, but these operations are varied.

The Grimorium Verum makes clear that all operations are performed with the assistance of spirits, but its methods include what we would call spells, and also methods of divination. Most often in these operations the sigils of appropriate spirits are involved in the procedure. There is for instance a traditional method of causing harm to an enemy through their

footprint. In its Verum form this involves tracing the sigils of spirits and stabbing a coffin nail into the print. Some of this methodology is reminiscent of modern applications of Austin Spare’s sigils, although rather more results oriented than the uses the artist himself employed. Incidentally, my speculation in The True Grimoire that Spare was acquainted with, and inspired by its contents has been verified by Gavin Semple, (see his introduction to Spare’s Two Tracts on Cartomancy}.

In general, Verum employs full-scale evocation for one main purpose, which is to form a pact with the spirit or spirits concerned, precisely so they will be willing to assist the magician in other types of operation. I say spirits in the plural for a reason. In contrast to the methodology of the Goetia of Solomon as popularly understood, Verum s process envisages the possibility of summoning more than one spirit at a time for the purpose of forming pacts. While any evocatory process is demanding, in terms of time and effort expended, this multiple evocation process is considerably more economical, and far more productive. Modern understanding envisages the conjuring of a single spirit in order to achieve one specific result, and the spirit concerned may never be met with again. Verum on the other hand envisages calling upon one or more spirits in order to commence a working relationship, so that on future occasions the same spirits may assist the magician. In these subsequent relations the full procedure of evocation is rarely necessary; and will usually only be employed to initiate relationships with additional spirits.

Such exhausting operations therefore are not the be all and end all of goetic sorcery. The magician and the spirits with whom they are involved will be active in a variety of other procedures. These will involve a range of different skills and activities, alongside a more minimalist conjuration.

The purposes of this book therefore should be becoming clear, although the work is not without considerable difficulties. One purpose is to reach behind the Classical Greek inheritance to reveal the older strata of chthonic religion. Another is to show, with demonstrations of continuity, the influence of both archaic practice and the archaic practitioner on what followed. This influence is traced in both the Classical and Hellenistic periods and the medieval and Renaissance magic of the grimoires, as well

as the interim period. In the course of this some familiar mythical and historical figures will be re-examined, and some much less familiar ones brought into the light.

Mythic Language

The purpose of a re-examination of Greek mythology may be questioned; what has it to do with goetia, aside from goetia being a Greek word? For one thing, its inclusion in this study is intended to bring the term howling, by which goetia is often translated, into its proper context. The spirit summoning aspect of the familiar grimoires is more or less compatible with Jewish and Christian culture, if not the religious authorities. Nothing in it remotely resembles howling, the attitude is one of sober and fearful piety. There is, like it or not, quite obviously another aspect of the grimoires and its folkloric background where quite other traditions are at work, which directly concern the term goetic and are more closely connected to its origins. This is the background for the mythological material included here.

It may still be asked, aside from the cultural distinctions, which are obviously significant, why the mythology? Part of a comprehensive reply concerns the nature of spirits, and of magical working that revolves around them. It is relatively unimportant whether such and such a spirit is the equivalent of such and such a mythic figure, or even an aspect of them. What is important is the fact that such figures had a myth, and were seen in mythical terms, and that this was a critical aspect of the magic in which they played a part. Even late demonologists, who spent time pedantically tabulating names of whose spelling they were never quite sure, were aware of the need for a story. Myth endows a spirit with a history, a family, a residence in the universe, and precedents for tasks undertaken on behalf of magicians and their clients.

Their likes and dislikes, and aspects of their story, also generally produce the basis for tables of correspondences. While these remain data in a table there is comparatively little magic in them. Endowed with a personality, the spirit becomes an active participant in the ritual, and in the creation of rituals. Reference tables are no replacement for the mythical

context of a spell, although with a little creativity they can partially substi-tute for the lack of one. That they can do this in fact demonstrates their reliance on such a context in the past, even if merely as a prototype. The loss of such a context is displayed in reliance on traditional rituals that are no longer understood, but cannot be adequately replaced. The ghost in the machine lingers even where the magician has no reference points for the background of the ritual employed. A mythology supplies such reference points, giving vitality to the composition and performance of ritual.

In recent decades a quiet revolution in mythological studies has taken place in the academic world with crucial relevance to goetic magic. Unsuspected by many modern occultists this revolution has gone beyond the antiquated and trivialised forms of myth; the glossy productions of the literary elite of the Classical period still perpetuated in modern coffee table books. Dieter Betz underlines this in his Introduction to the Greek Magical Papyri. These papyri are full of references to an older stratum of Greek mythology, in which the gods are not portrayed in genteel Hellenistic forms but as: capricious, demonic, and even dangerous. These are the gods of the local cults and of the popular forms of myth, more primitive and primal, above all more genuine. Although finding this material in the papyri appears to surprise the editor of the collection there is really no reason why it should. Although - as he remarks - the papyri are thus a primary source for the study of Greek folklore, the reverse is equally true: the more primal forms of myth are the bedrock of goetic magic.

Whereas literary sources for mythology begin a few hundred years bce their origins precede these by thousands of years. Of the two earliest sources, Homer - the great ancestor of Western literature - is more problematic than Hesiod. Lack of Homeric precedent cannot be automatically taken as proof that such-and-such a theme is of a later date. As observed by Dorothea Wender, Homer erases from the history of the gods all traces of incestuous relationships, he also suppresses the castration of Ouranos and the child-eating of Kronos. In short, he removes all evidence of their more primitive beginnings; just as he has excised much evidence of magical practices, human-sacrifice and homosexuality among his human cast. There can be no doubt whatever that what he has taken such pains to

erase was nonetheless present from the earliest times. That later sources often include these themes is not indicative of innovation or fabrication simply because absent from Homer, even allowing for subsequent changes in form and expression.

For, much as the idealised human forms of the Olympian gods suit the prejudices of later rationalism, it is not true that in the beginning people made the gods in their own image. In the beginning, people made the gods in the images in which they saw the gods; like lightning, like volcanoes, like water, like powerful beasts, like life giving or mind altering plants. Until the landlord asked people if they didn’t think the gods were more like him, and his friend the judge, and the judge’s friend the king, and like the priest, and their friends, and their husbands, wives and mistresses. Gods such as these are neither themselves nor the people they idealise.

Hesiod by contrast, while roughly contemporary with the Homeric texts, retains much that is primitive, with the major exception of his portrayal of Zeus. It is readily apparent that in the original form of the myth Zeus was taken in by the trickster Prometheus, while Hesiod portrays him as infallible, allowing Prometheus to think him fooled for his own reasons. Similarly, Hesiod down-plays Zeus’ dethronement of Kronos; as an exemplar of rebellion against parental authority such an act was unworthy of the paradigm of fatherhood himself. These examples are enough to warn us against taking the forms of myths as presented by the literary elite for true representations of more primitive phases of religion. They are retellings, often distorted by tendencies to rationalise or to promote later views. In using literary sources then, rather than take the retelling at face value, the purpose is to unearth traces of older belief in what remains.

The contrast between Homer and Hesiod is particularly illustrative. Homer wrote for an aristocratic audience and lived in Asia Minor, the birthplace of Greek philosophy and much of its higher culture. Hesiod on the other hand lived in rustic Boeotia on the Greek mainland, the literary tradition of which he was part produced among other things divina-tory manuals, almanacs and - interestingly enough - handbooks of metal working. It is precisely in this unlearned’ context that the real roots of Greek religion are to be traced and its true character discerned. In his

Introduction to the Magical Papyri, Betz directs us - in note 46 - to another note in a scholarly article by A. A. Barb. The quotation is given below with due emphasis. While appearing in a footnote (both in Betz and in Barb) it is enormously important. In an interesting study of the Gnostic gems, comparing their Greek and oriental elements, Barb speaks of the comparatively recent recognition of ancient Oriental influences on Greek religion, and by extension magic. While the Papyri are full of oriental elements - cheek by jowl as it were with classical materials - until recently this juxtaposition was viewed as late syncretism, having no relevance for ancient Greek religion. In a delightfully incisive summation, Barb completely reverses this: so far from being late syncretism, in many important respects it is: the ancient and original form of popular religion coming to the surface when the whitewash of ’classical’ writers and artists begins to peel off. That this material should form in very large part the background of the magical papyri underlines the necessity for a reappraisal of myth by modern magicians.

So what is myth? Many answers are possible; one of the most interesting and influential definitions in the early 20th century was that myths were stories explaining pre-existent ritual usage. The academic reappraisals of this idea are relevant in their own sphere. However, the speculative use of mythic emblems for philosophical purposes is a not dissimilar concept of great relevance to our purpose. In other words, this might not explain the origins of all myths, but it does relate to how myth might be understood by Greek magicians, among others.

So there is another aspect to the question, which is, if mythology is a language, how does it work? Before really addressing this, some examples are useful to illustrate the innate flexibility of mythological language. Some are implicit among the themes explored herein: in the myths of the birth of Athene from the head of Zeus some uncertainty about roles is seen; was it Prometheus or Hephaestus, both Lords of Fire, who struck the blow? How could Hephaestus - the limping god - have done it if Hera created him in revenge for the birth of Athene? The mythic birth of Dionysus from the thigh of Zeus involves further apparent confusion of roles. If Zeus is lame when Dionysus is in his thigh, is Zeus

then Hephaestus? When Dionysus fetches Hephaestus back to Olympus, drunk and seated on an ass, is Hephaistus then Silenus? When Dionysus conquers the world including India he is portrayed as bearded, no longer the eternal youth; which of the elder gods is he then, is he Hades, is he Silenus? Or is he Zeus himself, of whom he was the infant form, then the son, to be finally the Father? In these scenes gods are seen at once as older and younger, dying and being born, tragic and comic. It is not that myth provides no clear cosmological system, but that it provides a language by which cosmological ideas are expressed, and by means of which they evolve. What is important is not that static forms neither define nor confine myth, but that myth gives life to otherwise static forms.

The mythological material presented here is active in precisely this way, it is demonstrative and suggestive in ways that tabulated data or analytical approaches are not and cannot be. As will be shown the roots of goetia involve gods of fire, and legendary magicians who discovered haematite iron. It will be shown too that goetia was strongly associated with the more emotionally charged, orgiastic aspects of religion. Orphic and Pythagorean associations represent a sublimating and rationalising reform of just such traditions. The Orphic and Pythagorean reforms of the older traditions of Dionysus or Demeter are personified by Apollo; now a solar god of reason, pursued in more restrained and directed religious ecstasies - the witch-doctor has become the philosopher.

In the Classical and Hellenistic periods it is to this more ethereal status that systems termed magic or theurgy aspired. Both theurgy and goetia borrowed from each other, and were never completely distinguished. The names of Orpheus and Zoroaster were intended to lend respectability to the rites and books composed in their names. In reality, Orphic rites reverted to chthonic forms even though seeking the Apollonian dignity of celestial religion, and the rites of the Magi - generally pre-Zoroastrian in origin - were as barbarous as the goetia Cumont supposed their rites were intended to replace. Myths were employed to describe this magic, to explain it, provide authors for its texts and founders for its schools. To reach back through the Orphic reforms to the more primitive levels necessarily involves examination of this mythic background.

My intention is not a complete historical reconstruction of magic and religion of a particular circumscribed historic period; this study involves several phases of the past for the purposes of the present. In any case such a result could not be achieved in this fashion; neither indeed is it likely to emerge from academic or archaeological disciplines. Orphism is still deeply controversial, and the interwoven themes of oriental and Greek magic and religion involve deeply complex questions pursued and understood by highly recondite specialists who nevertheless disagree on many fundamental issues.

Nevertheless, looking at and behind them for contemporary magical purposes is not so difficult, in the manner and for the purpose involved here. The purpose of academic historical disciplines is to understand peoples of older cultures, how they thought, how they behaved. Even so, empathically seeking to apply this understanding in contemporary life is never the stated intention. Reaching behind Orphism in the way undertaken here reveals not a historical but a mythic past. I am not drawing a family tree of dates, times and places in which oriental and Greek ideas influenced one another. The relationship of the Orphic reforms and of goetia with the Dionysian currents provides a creation myth for transforming modern magic. This creation is conceptually prior to the emergence of Goetia and its involvement with older religious traditions; it is not intended to be strictly historical. Considered in strict socio-historical terms of linear time and geographical space, traditions concerning ancient gods and magical books often appear compartmentalised and distinct, but this was never the way that they were understood. Consequently this mythic past is essential to a revitalised and practical pagan goetia in the here and now.

It requires emphasizing here that my use of mythic language to elucidate goetia, while separate from archeology and formal academia of that sort, is also distinct from theological and philosophical approaches. These might have allowed me to pursue a high-brow extension of mainstream Hermetic and Qabalistic magic. However, while simpler, such an approach would be anaemic and fall far short of my underlying intent. Nevertheless, while distinct from all these approaches, do not imagine

that Geosophia has neither precedent nor direction. There is a clear direction underpinning the entire work, which shares its precedent with the ancient specialists in necromancy and initiation into the Mystery cults.

The essential concerns of Orphic initiates and of goetic magicians or necromancers were and are primarily in one field. Ancient and modern syntheses alike are necessarily rooted in eschatology. Or to express it in still simpler terms: death, judgement, heaven and hell. These concerns fundamentally shaped the worldview and procedure of the papyri and the grimoires; by their very nature, they are as central to the postmodern synthesis of magic. Eschatology dictated the purposes of ritual, its structure, mechanisms and individual components. More fundamentally still, these concerns shaped perceptions of and responses to the world of spirits.

Many of the mythic figures and stories recounted in the course of this work may be unfamiliar, but they are vitally important to the study. The fact is that not only was Greek myth reshaped by the ancient literary elite, but also that until recently classical learning was the exclusive preserve of their latter day counterparts. The preferences of both were served by particular emphases, leading to the comparative neglect of others for many hundreds of years. Magicians have frequently concerned themselves with neglected or marginalised traditions; in very large degree this now includes Classical learning, stripped of the emphases involved in its former establishment form. The chthonic traditions, which were intimately concerned with the origins of later magic, were already marginalised by the end of the Grieco-Roman era, and classicists until very recent times shared similar prejudices. In my opinion this is ample justification for the emphasis in this study upon mythological material; concerned not with the Olympian state religion, but the chthonic cults and other traditions which underpinned goetia.

Before proceeding with the examination in the manner outlined here, a few simple points require re-emphasis. The identity of the operator makes goetia what it is, not the good or bad nature of the spirits involved. Sun and Moon are both as important to goetia as to astrology, but then astrology itself has a fundamentally geocentric foundation. In the same way, goetia focuses on earth and the underworld. It relies not on authority

from the celestial regions - the so-called adversarial angels of aristocratic magic in the Jewish and Christian tradition — but the innate power of the magician. It has its own worldview - of which theology and philosophy are later sublimated forms - and far from being a specialised sub-discipline, it is the primal origin of the entire Western tradition of magic.

GOETIC TIMELINE

8350 bce: Neolithic foundation of Jericho, first walled town.

6250 bce: Neolithic foundation of Catal Hayuk in Anatolia. Produces images of a goddess between two lions, resembling later Cybele.

6000 bce: Island of Crete occupied from mainland.

4000 bce: Bronze Age begins in the Middle East.

4000 bce: Pottery finds suggest Libyan immigration to Crete, possibly due to expanding Egyptian hegemony.

3500 bce: Thracian Copper Age; produces gold horse harness decorations, the oldest gold artefacts in Europe.

3200 bce: Writing developed in Sumer and Egypt, beginnings of written history in dynastic lists maintained by priesthoods.

2900/2600 bce: Cretan Bronze Age begins, Early Minoan or pre-palace period.

2400 bce: Troy exerts economic dominance, controlling Black Sea trade.

2000 bce: Middle Minoan, first palace period.

1600 bce: Beginnings of Mycenaean civilisation in Greece; Zancle (later called Messene) founded in Sicily.

1580 bce: Late Minoan.

1450 bce: Destruction of Minoan Crete, followed by partial revival.

1453 bce, 1222 bce, 884 bce: Legendary founding of the Olympic games.

/@/

1250 bce: The likely historical period of the Black Sea expedition of the Argonauts and of the Trojan War. Homer portrays difficulties at home attending their return. Hittite references describe the Ahhiyawa (Achaean) king as equal to the Hittite king.

1219 bce: An attempted migration of'Sea Peoples’, likely including landless Mycenaean warriors (Achaeans), allied to Libyans is repulsed by Egypt.

1200 bce: A period marked by widespread economic turmoil and the depredations of the Sea Peoples. The beginning of the collapse of Mycenaean culture, the likely causes are nowadays considered to be inter-state strife and revolts against the palaces by the general population, rather than Dorian invasion. Palace sites destroyed or abandoned. The Hittite Kingdom falls, and Egypt loses its Asiatic possessions. In the course of this century the Dorian Greeks penetrate into Peloponnesian Greece and the Phrygians into Asia Minor.

1174 bce: Rameses III repulses another attempted migration by the Sea Peoples.

1100 bce: The Dorians spread to Crete, bringing the final end of Minoan culture. The former Mycenaeans retire from the Peloponnese into Arcadia and into Attica and particularly Athens.

1050 bce: Phrygians established as successors to the Hittites in Anatolia. 1000-800 bce: Dark Ages (Greek); the period sees mass migration to Asia Minor, the birthplace of Greek philosophy.

959 bce: Solomon builds the Temple.

945 bce: Visit of the Queen of Sheba, Solomon’s fall into idolatory. A Libyan dynasty rules in Egypt. Oracles are important to Egypt’s Theban priesthood.

931 bce: Death of Solomon.

900-800 bce: The approximate period of Homer.

archaic period - early classical

800-400 bce: Major phase of Greek colonisation throughout the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions.

776 bce: The traditional date of the Foundation of the Pan-Hellenic Olympics, rise of the city state: Classical Period begins.

732 bce: Syracuse founded in Sicily by a Corinthian Greek named Archias.

670 bce: Gyges king in Lydia, Assyria at war with Egypt.

GOETIC TIMELINE

630 bce: The city of Cyrene in Libya is built by colonists from the island of Thera.

590 bce: This is the likely period of Zoroaster’s reforms of Persian religion, from polytheism comparable to Vedic Indian to worship of a single god, Ahura Mazda.

597-585 bce: The beginnings of Babylonian exile of the Jewish people. Fundamental developments, including the Books of Moses, were shaped during this time.

580 bce: Agrigentum founded in Sicily by the Greeks (Greek colonists were active in Sicily from 750 bce to 5th century bce).

583 bce: Fall of Babylonian Empire to Cyrus of Persia, the end of the Jewish exile; rebuilding of the Temple.

500 bce: Beginnings of Roman control in Italy.

400 bce: Thousands of Greeks serve as mercenaries overseas ('the best heavy infantry in the world’).

428 to 348 bce: Plato, the hugely influential philosopher, mentioned goes in company with pharmaceus - an enchanter with drugs - and sophists, used in the derogatory sense of cheats.

342 bce: Aeschines, an Athenian orator, in a speech impeaching Ctesiphon linked the terms goes and magos in a derogatory sense.

HELLENISTIC OR LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD

334 bce: Alexander the Great crosses the Hellespont and defeats the Persian Empire. Hellenistic Period, cosmopolitan model replaces civilisation of the polis.

264 bce: Romans control Italian peninsula.

185 bce: Romans dominate Eastern Mediterranean.

44 bce: Rome controls the entire Mediterranean.

The World of the Argonauts

THRACE

Q

Greece and Asia Minor

Magna Graxia

M Y S I A

Phrygia, Syria and Egypt

Blessed is he who knows the gods of the fields, And Pan, and aged Syfvanus, and the sifter Nymphs.

Virgil’s Georgies II. 490

Quoted in The Humid Path by Sir Edward Kelley

GOETIA & THE GRIMOIRES

I composed a certain work wherein I rehearsed the secret of secrets, in which I have preserved them hidden, and I have also therein concealed all secrets whatsoever of magical arts of all the masters; all secrets or experiments, namely, of these sciences which are in any way worth being accomplished. Also I have written them in this Key, so that like as a key openeth a treasure-house, so this alone may open the knowledge and understanding of magical arts and sciences.

The True Grimoire

Old magical manuals are reasonably numerous, although perhaps the majority of well known ones are in part compilations or reconstructions drawing on the writings of learned commentators upon older and rarer works. Despite this availability it is sometimes quite difficult to obtain a clear picture of what magical ceremonies were actually like in the period 1200 to 1750 ad. Curiously enough there is a neglected but extremely useful text by which this obscurity may be lifted, and some modern misconceptions dispelled. A most complete eye witness account of magical ceremonies of the medieval and Renaissance period is contained in the lively and highly readable autobiography, The Life of Benvenuto Cellini. The quotations that follow provide all the information Cellini supplied. Although this appears in part in Skinner and Rankine’s The Veritable Key of Solomon I have quoted at greater length to supply the reader with all the relevant information, and interspersed an extended commentary on several of the significant details that arise. I have made use of two English translations of this work, that of Robert H. Hobart Cust and the older translation by John Addington Symonds. While each is well regarded there are distinct advantages to consulting both. Symonds text is more elegant and readable in some respects, but Cust is less constrained by Victorian reserve. Judging from his footnotes Cust was perhaps also better acquainted with magical literature than Symonds, and decidedly more so than Symonds’ commentators.

The reality of Cellini’s participation in the rituals described need not be doubted. His was a tempestuous and uninhibited spirit to which action was second nature, and dissimulation a stranger.

It happened to me through certain curious chances that I became intimate with a certain Sicilian priest, who was of a very lofty genius and very learned in Greek and Latin literature. It occurred on one occasion in the course of a conversation that he chanced to £]oeak of the Art of Necromancy; regarding which I said: Throughout my whole life I have had the modi intense desire to see or learn something of this Art. To which remarks the priest rejoined: That man who enters upon such an undertaking has need of a dlout heart and firm courage. I answered that of stoutness of heart and firmness of courage I had enough and to ^are, provided the opportunity. Thereupon the priest answered: If you have the heart to dare it, I will amply satisfy your desire. Accordingly we agreed upon attempting the adventure.

This meeting took place in 1535, significant in the history of magic as the year of Cornelius Agrippa’s death. This was two years after the first complete publication of his Occult Philosophy and five years after the publication of The Uncertainty and Vanity of the Sciences. It was also thirty years before the publication of the more practical Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy. Regarding this latter book, controversy still reigns as to whether or not Agrippa wrote it; in truth only parts of it claim to be written by him, which it is at least possible that they were. At the time of Cellini’s experience some of these writings had been circulating in manuscript for some time, and they certainly could have been consulted by the heroes of this narrative. In any case, as will appear, the varieties of ceremonial magic these writings describe were indeed in contemporary use. It is of the very first importance to note that this Sicilian necromancer was, like Agrippa, no stranger to Classical literature. Such familiarity is usually understated in the grimoires, and even more so by moderns over-influenced by Kabbalistic interpretations. In reality to practice magic influenced by the pagan past was highly suspect (to read Greek is to turn heretic’), so

such influence was usually disguised or disavowed. Its presence and influence was nevertheless very strong. Considering this Classical background the location of the necromantic experiment is rather appropriate:

The priest one evening got everything in order, and bade me find a companion or two. I invited Vincenzio Romoli my very great friend, and the priest brought with him a man from Pisfloja, who also studied Necromancy. Proceeding to the Coliseum, the priest having robed himself there after the manner of necromancers, set himself to drawing circles on the ground with the moff elaborate ceremonial that it is possible to imagine in the world; and he had made us bring precious essences and materials for lighting a fire, besides some evil smelling drugs (asafoetida). When all was in readiness, he made the entrance into the circle; and taking us by the hand one by one he set us within the circle; then he allotted our duties; he gave the pentacle into the hand of that other necromancer his companion; to us others the care of the fire for the perfumes; then he betook himself to his incantations.

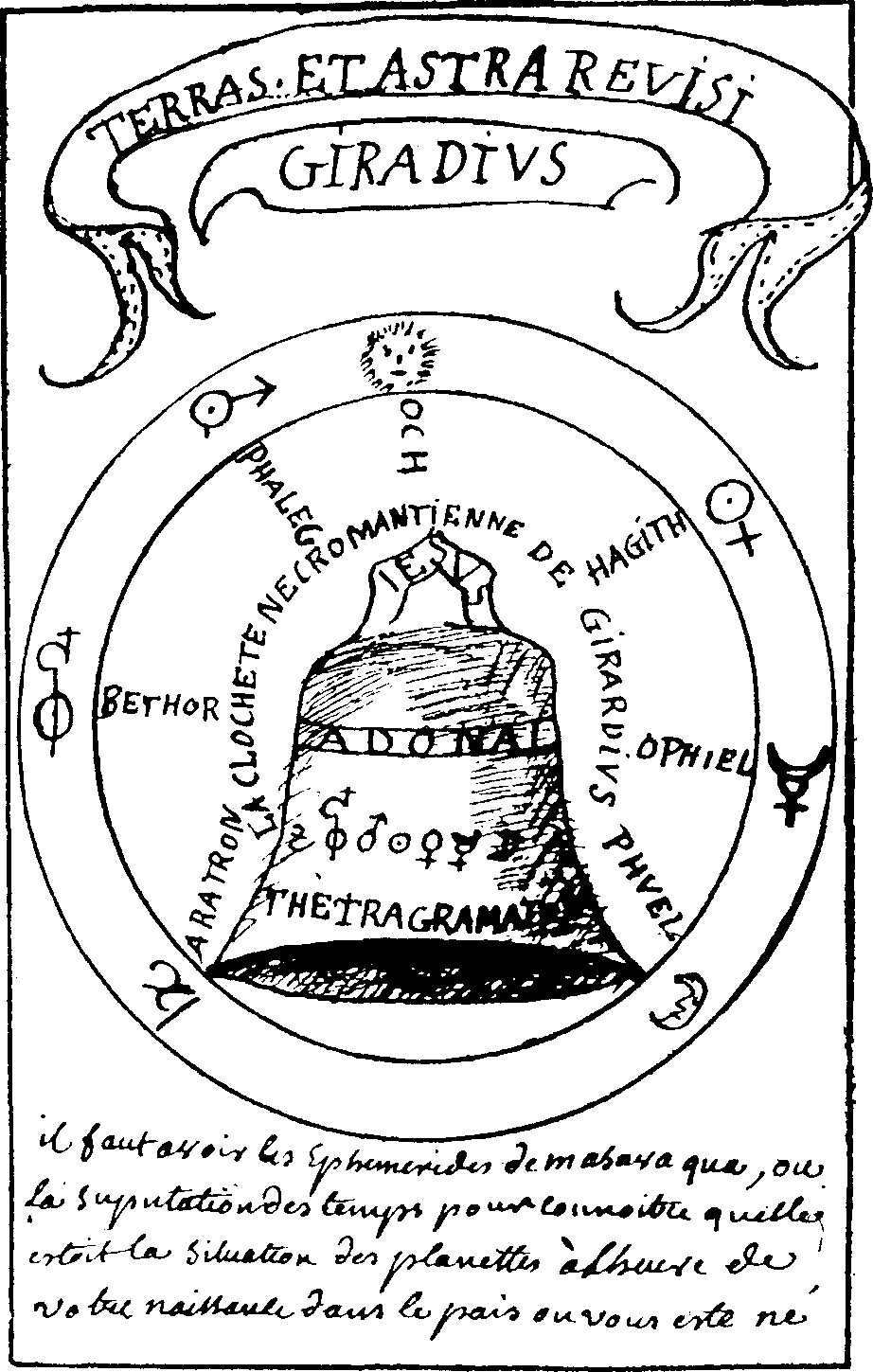

The elaborate nature of the circle is not a sufficient clue for us to ascertain which text the necromancer was using. At this date it may well have been a circle from the Heptameron which was available in Italy from 1496, and likely earlier in manuscript form. The Heptameron sets forth rules for drawing circles that are detailed and elaborate, but there is no solid indication in the text that this was the form used.

The insistence on a companion is typical of the Key of Solomon, however the use to which asafoetida is put later in this rite is quite different from that of the Key. Of particular interest to me is the apparent use of a single fire which appears to have been of reasonable, even substantial, size. This is in accord with such texts as the Grimorium Verum and the Grand Grimoire. These are often supposed to be semi-spurious and of later date, but in fact preserve authentic traditions not found in the Key and other less overtly demonic grimoires. On the other hand a single censer — also described as a fire - is recommended by the Heptameron. However, the use of multiple perfumes also resembles the Grimorium Verum while utterly

distinct from the Heptameron which attributes a single perfume to each day of the week. Judging from descriptions and the occasional illustration in various grimoires, this fire or single censer took the form of what we nowadays would call a brazier. It is noteworthy that the Grimorium Verum and other late French grimoires uniformly retain this feature.

This business lasted more than an hour and a half; there appeared several legions of £jairits, to such an extent that the Coliseum was quite full of them. I was looking after the perfumes, when the priest became aware that there were so large a number present, and turning to me said: Benvenuto, ask them something. I called on them to reunite me with my Sicilian Angelica. On that night we received no answer; but I took the very greatest satisfaction from it, my interest being much encouraged.

'This business’ evidently alludes to the construction of the circle and the recital of conjurations. Modern ceremonial is often more abbreviated, and, let it be said, less effective. A preliminary banishing ritual and invocations as prescribed by nineteenth century magicians might take half this time.

Note too that there is absolutely no mention of any triangle of manifestation outside the circle. This adjunct to evocations probably is not a consistent feature of the grimoires. In its modern form it derives from mention by Weyer, elaborated in the Goetia of Solomon, and taken for granted by most modern magicians. That it would serve no purpose whatever when legions of spirits appear, being large enough for one human sized entity at the most, does rather militate against its utility in some conceptions of magical procedures.

The necromancer said that it would be necessary for us to go another time, and that I should be satisfied in re^aedt of all that I asked, but that he wished me to take with me a little lad of pure virginity. I took one of my shop-boys, who was about twelve years old, and I invited Vincenzio Romoli again; and a certain Agnolino Gaddi, who was our intimate friend.

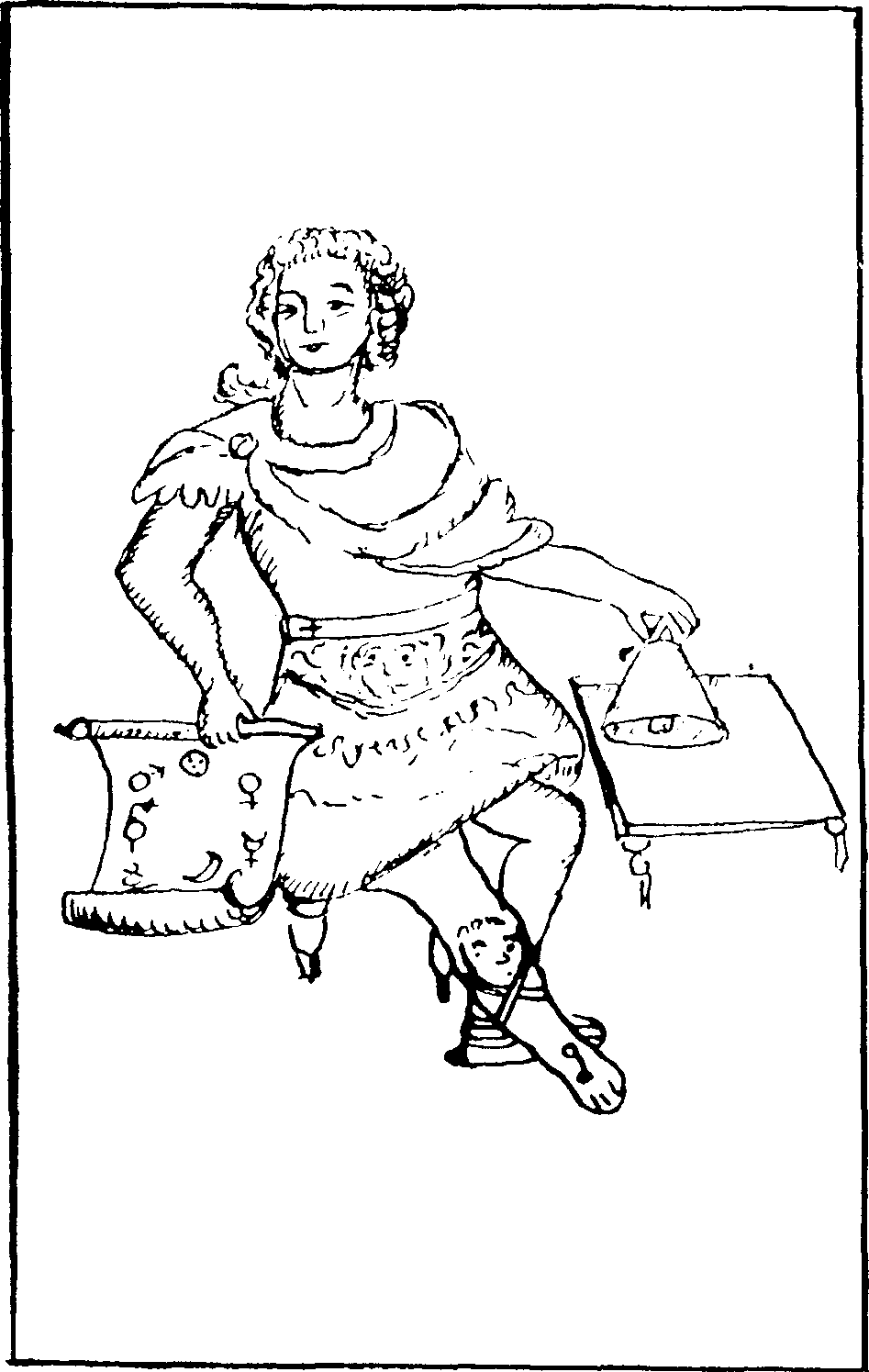

This employment of a child clairvoyant is typical of many operations in the papyri. These evolved into the Art Armadel, a highly influential procedure which is incorporated in many important grimoires. A detailed commentary on this type of operation can be found in my edition of The True Grimoire. Here it is only necessary to say that the rite is undoubtedly ancient, providing clear evidence of the pre-Christian precursors of the grimoires.

When we arrived again at the appointed ^oot, the necromancer having made the same preparations with that same and even more wonderful precision, set us within the circle, which he had again made with more wondrous art and more wondrous ceremonies; then to my friend Vincenzio he gave the charge of the perfumes and of the fire; and with him the said Agnolino Gaddi; then he put the pentacle into my hand, which he told me that I muS turn in the direction towards the points he indicated to me, and beneath the pentacle I stationed that little lad, my shop-boy.

This use of the pentacle is important, details of its construction or appearance being present in many grimoires without clear instructions on its use. In The True Grimoire it is recommended that such a pentacle be placed at the four points of the compass. In the Key of Solomon other pentacles are to be worn by the magician beneath a veil and shown to the spirits at need. The procedure here appears to combine both approaches, and reflects the older traditions regarding a Seal or Pentacle of Solomon. The form in the Key is probably considerably later, numerous complex and specialised pentacles replacing the single ubiquitous form of the singular Pentacle of Solomon.

The necromancer commenced to utter those very terrible invocations, calling by name a multitude of demons, the chiefs of legions of ^irits, and summoned them by the Virtue and Power of God, the Uncreated, Living and Eternal, in the Hebrew language, and very frequently besides in Greek and Latin; to such purpose that in a short ^ace of time they

filled the whole Coliseum a hundredfold as many as had appeared that firft time. Vincenzio Romoli, together with Agnolino attended to keeping up the fire, and heaped on quantities of precious perfumes. I, by the advice of the necromancer, again asked that I might be reunited with Angelica. The necromancer turning to me said: Do you hear what they have told you? That within the flace of one month you will he where she is? Then again he prayed me to £tand firm by him, for the legions were a thousandfold more than he had summoned, and that they were the moft dangerous of infernal TJoirits; and since they had settled what I had asked, it was necessary to be civil to them; and patiently dismiss them.

The phrase’Virtue and Power of God’ bears some resemblance to the text called the Ars Notoria, while a similar expression occurs in the Key; however the term may be a general one. It is plain enough that the spirits answered the question of the necromancer, and while terrified he was ready enough to deal with them without threats or curses.

On the other hand the lad who was beneath the pentacle, in greatest terror said, there were a million of the fiercest men swarming round and threatening us. He said besides that four enormous giants had appeared, who were striving to force their way into the circle. All the while the necromancer, trembling with fright, endeavoured with mild and gentle persuasions to dismiss them. Vincenzio Romoli, who was trembling like a reed in the wind, looked after the perfumes. I, who was as much in fear as the red:, endeavoured to show less, and to incite them all with the mod marvellous courage; but the truth is I thought myself a dead man on seeing the terror of the necromancer himself. The lad had placed his head between his knees, saying: This is how I will meet death, for we are all dead men. Again I said to the lad: These creatures are all inferior to us, and what you see is hut smoke and shadow; therefore raise your eyes. When he had raised them, he cried out again: The whole Coliseum is inflames, and theflre is coming down upon us: and covering his face with his hands, he said again that he was dead, and that he could not endure the sight any longer.

The position of the child seer beneath the pentacle is interesting, it underlines the protective nature of the symbol and additionally suggests that Cellini turned the pentacle this way and that rather than carry it to the various quarters. The impression created by these references implies that the pentacle was of a fairly large size, probably requiring both hands. The pentacle would be made from the virgin parchment upon which such emphasis is placed in many grimoires. The reader should bear in mind its central place in such magic, and that the parchment was obtained from a sacrificed goat or lamb. This vital talismanic object has unsuspected ancient roots in remote antiquity, which will be examined in Book Two.

As Skinner and Rankine note, the four enormous giants, who cannot have been gathered at a single point, may well represent the Four Kings of the Cardinal Points who are frequently mentioned in goetic texts. In the midst of the ceremony Cellini declared that the spirits are inferior to humans, who according to holy writ have a special place in God’s dispensation. In context this has the ring of vainglory, an attempt to inspire courage rather than a statement of confident belief.

The necromancer appealed to me to keep steady, and to diredt them to throw asafoetida upon the coals: so turning to Vincenzio Romoli I told him to make the fumigation at once. While I sjxike, I was looking at Agnolino Gaddi, whose eyes were starting from their sockets in his terror, and who was more than half dead, and said to him: Agnolo, at times such as this one muil not yield to fear, but give oneself to action; therefore flir yourself and fling a handfol oj asafoetida on the fire. Agnolo, in that moment as he moved, made a flatulent trumpeting with so great an abundance of excrement as was much more powerful than the asafoetida. The lad at that horrible stench and that noise raised his face a little, on hearing me laugh, and plucking up courage, he said that the ^>irits were departing in great ha£te.

The use of asafoetida as a banishing agent is by no means unknown, but it is necessary to distinguish its use in this way from the procedures of both the Key oj Solomon and the Goetia of Solomon. In both these texts

asafoetida is used in the last resort as part of a contraining method to force reluctant spirits to appear. Here the use of stinking odours is all too plainly employed to banish spirits.

Thus we continued until the bells began to ring for matins. Again the lad told us that but few remained, and those at a distance. When the necromancer had completed all the remainder of his ceremonies, having unrobed and repacked a great bundle of books that he had brought, we all together issued with him from the circle, huddling ourselves close to one another; e^ecially the lad, who was placed in the middle, and had taken hold of the necromancer by his gown and of me by my cloak; and continually whilst we were going towards our homes near the Banks, he kept on telling us that two of those ^>irits he had seen in the Coliseum were going gambolling along in front of us, sometimes skipping along the roofs, and sometimes upon the ground.

Matins may represent midnight or daybreak. It is very interesting that the necromancer has a bundle of books with him, rather than a single grimoi-re. This accounts for many features of this rite, such as the conjurations in different languages. Some modern magicians have a tendency to purism, treating specific grimoires as ’things in themselves’. This eschewing as eclectic any practical or theoretical combination of sources contrasts strongly with the method of this authentic Renaissance magician.

Our necromancer has evidently performed the necessary rites of dismissal (the license to depart), but despite this there are still spirits to be seen on leaving the circle. This contrasts strongly with the usual advice of the grimoires to be absolutely certain the spirits have departed before quitting the circle. Presumably the gambolling spirits accompanying their homeward journey were deemed of a less ferocious order. From another perspective, post ritual visions of this kind are only to be expected, the contrary advice of the grimoires is perhaps a little mechanistic.

The necromancer said that often as he had entered magic circles, he had never encountered so great an adventure as this. He also tried to

persuade me to consent to join with him in consecrating a book, by means of which we should derive immeasurable wealth, since we could call up the demons to show us some of the treasures of which the earth is full, and that by that means we should become very rich; and that love-affairs like mine were vanities and follies of no consequence. I replied that if I knew the Latin language I would be very willing to do such a thing. Nevertheless he continued to persuade me, saying that the Latin language would serve me to no purpose, and that if he desired he could have found many persons well-insdrucled in Latin; but that he had never found anyone of as sound a courage as I had, and that I ought to attend to his counsel. With these discussions we arrived at our homes, and each one of us dreamed of devils the whole of that night. As we were in the habit of meeting daily, the necromancer kept urging me towards that undertaking. Accordingly I asked him what time it would take, and where we should have to go. To this he replied that in less than one month we could conclude the matter, and that the place mod adapted for it was in the mountains of Norcia; a master of his had consecrated such a book nearer to Rome at a place called the Badia di Farfa; but he had met with some difficulties there, which would not occur in the mountains of Norcia; the Norcian peasants are trustworthy persons, and have some practice in such matters, so that they can when necessary render valuable assistance.

As will subsequently be seen, the location the necromancer speaks of is an important focus of pagan survivals and folklore traditions. These are of great interest in themselves. That they were not entirely separate from the ’Juda-’o-Christian’ magic of the grimoires, which were the province of a literate clergy, is particularly significant. It is too often supposed that the magic of the grimoires reflects only the Christianised magic of a clerical underground, an adaptation of exorcism techniques and so forth. An arbitrary distinction is often drawn between folk magic and this ecclesiastical species. Such a distinction leads to circular arguments, where magical texts deviating from the definition are termed pseudo-grimoires. In reality such folkloric elements are present to a greater or lesser degree in the ma

jority of grimoires; those that emphasise it more than others may well be more representative rather than less.

This prieTtly necromancer moved me so much by his persuasions that I was well di^osed to the deed, but I said that I wanted fir£t to finish those medals that I was making for the Pope. I confided what I was doing concerning them to this man alone, begging him to keep them secret. At the same time I never gave up asking him if he believed I should be reunited with my Sicilian Angelica at the time indicated; for the time was drawing near, and it seemed me a singular thing that I heard nothing of her. The necromancer assured me that I should mofl certainly find myself where she was, because the spirits never fail, when they make promises as they had then done; but that I mud keep my eyes open, and be on my guard against misfortune that might happen to me in that connection, and to put restraint on myself to endure somewhat against my inclination, for he foresaw an imminent danger therein; well would it be for me if I went with him to consecrate the book, since this would avert the peril that menaced me, and would make us both mod fortunate...

Here Cellini’s adventures with the necromancer come to an end. A great danger did come upon him, as predicted by the necromancer, and fleeing the city in consequence he was unexpectedly re-united with the Sicilian Angelica within the allotted time. Since the necromancer never appears again it can only be assumed that he had left for Norcia in Cellini’s absence. It is unfortunate that the artist did not accompany the necromancer to Norcia to consecrate the Book of Spirits, and share that adventure with us. Before taking our magical book to the mountain of the Sibyl in Book Two, another important journey awaits us.

THE argonautica: BOOK I

PREPARATION & DEPARTURE

Phrixus died, and was buried, but his ^>irit had no re&; for he was buried far from his native land, and the pleasant hills of Hellas. So he came in dreams to the heroes of the Minyai, and called sadly by their beds, ’Come and set my spirit free, that I may go home to my fathers and to my kinsfolk, and the pleasant Minyan land.’ And they asked, ’How shall we set your spirit free?’ ’You mu ft sail over the sea to Colchis, and bring home the Golden Fleece; and then my spirit will come back with it, and I shall sleep with my fathers and have reft.’

Charles Kingsley, The dferoes

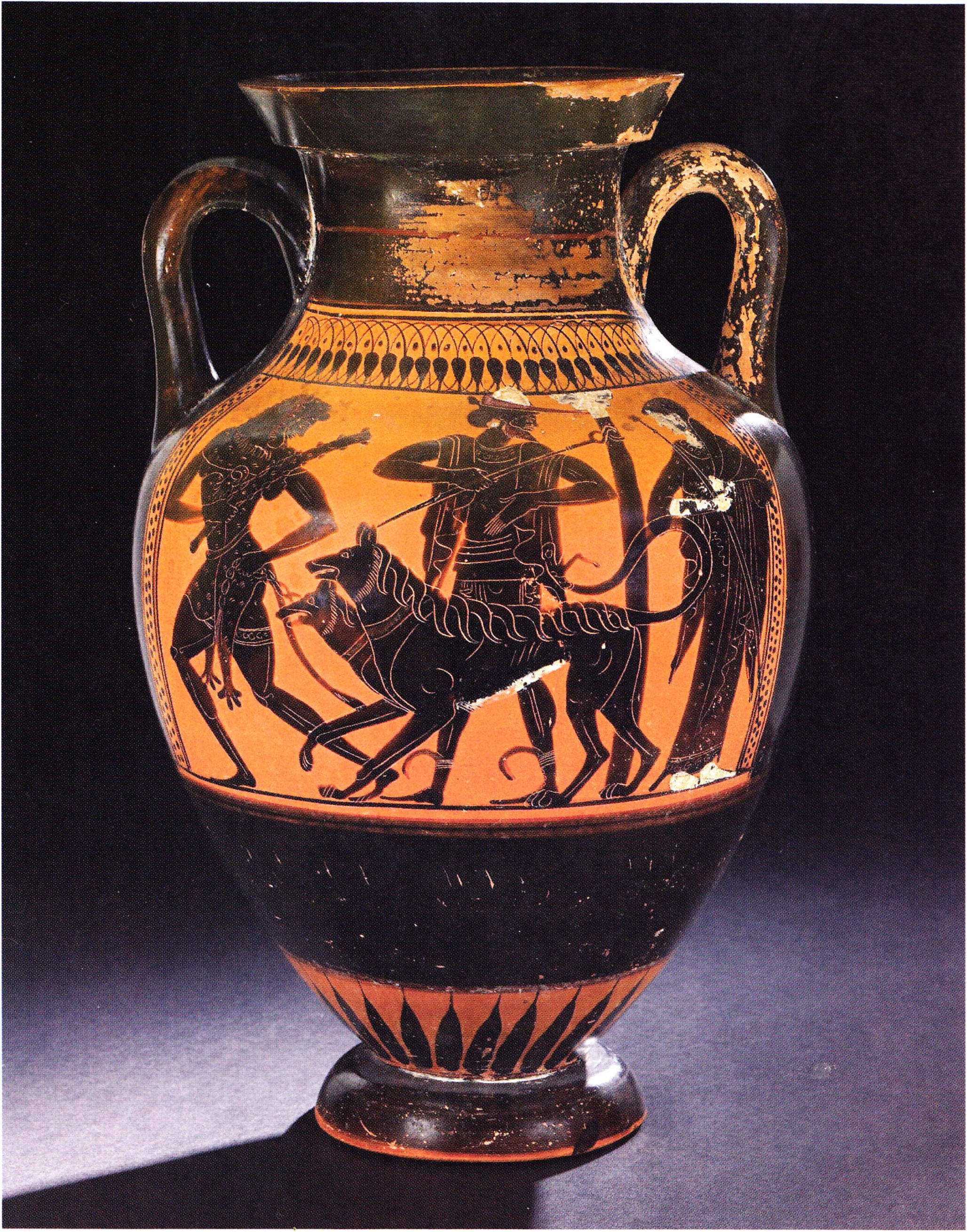

W/Z hen this book began it was as part of a commentary on the \ > Grimorium Verum, which expanded into a history of goetic magic ▼ ▼ and an exploration of its earliest roots and mythos. Quite unexpectedly, in the process of elucidating the history of magic in the world of the Greeks, the voyage of the Argonauts emerged as a major theme. In time, as work progressed, there arose the need for a structure intercon

necting the themes involved. These concerned geographical and ethnological issues, as well as the evolution of rituals and other aspects of goetic magic. The travels of the Argonauts presented such a structure: their voyage at once representing shamanic travel, the rise, fall and renaissance of chthonic religion, and an interconnecting route through the Mystery cults and foreign influences on Greek traditions.

In the preliminary stages of expanding the work to cover the wider historical concerns, the need for a gallery of important characters, historical and mythical became apparent. Many of these characters were involved in some way with the Voyage of the Argo, or Argonautica. Additionally, the resemblance of this gallery to the roll call of crew members at the beginning of the Argonautica was striking and strangely appealing. It also became

apparent that many other topics important to the study were involved in the voyage of the Argo. The geography of the Argonautica suited my purposes very well; a shamanic journey from Thessaly, land of classical witchcraft to Colchis home of the major witch figures of classical myth. One the way important sites and persons are encountered, and the return travels across Europe (represented by the grimoires) to the west coast of Italy and an African climax.

Accordingly, without more ado, the Argonautica became part and parcel of the structure of the work. At first glance an epic poem may seem a distant concern from elucidating the background to the magic of the grimoires. If present, this impression will hopefully disappear as the reader undertakes the journey involved. The decision to make a commentary on the Argonautica a key element of the book has an additional virtue. Many references to the Greek elements in occultism focus on Hermeticism or other philosophical traditions. Goetia is older than any of these, being more closely related to the roots of mythology in archaic ritual. The Argonautica is an excellent vehicle for introducing themes of this nature.

The only complete text of this ancient legend is the Argonautica composed by Apollonius of Rhodes. This is a much later composition than the Homeric epics, which the author consciously imitated in many respects. Apollonius was a resident of Alexandria, then the intellectual centre of the world. He was to become the director of the famous Library in the time of Ptolemy the Third. His first attempt at writing this poem was so badly received that he retired to Rhodes. Here he revised his text, and returned to a triumphant reception in Alexandria. Unlike other poets of his time Apollonius did not break with older poetic tradition but built on it. This and his unparalleled access to ancient literature and earlier versions of the legend is a major compensation for the comparative lateness of the text, which dates from the middle of the third century bce.

An important difference from Homer is Apollonius' strong sympathy with the old Mystery cults, and dissatisfaction with the Olympian state religion. In this he is typical of many intellectuals, in Alexandria and throughout the Hellenistic world. This represents the revival of chthonic religious traditions, of which Orphism was a potent cause. Some have

gone so far as to call the Argonautica an Orphic book in its own right. There is a strong shamanic motif central to the epic, which has as one of its objectives the recovery of a soul from a distant place: For Phrixus bid-deth us go to the halls of Aeetes, and bring his spirit home (Pindars Pythian Ode IV). In part this explains the attraction of the theme for an author of Apollonius’ sympathies, as also its relevance to our study.

Those familiar with the story will doubtless be aware that many aspects of the voyage are geographically impossible. One reason is the relative ignorance of geography when the epic first took shape, setting precedents which better informed later writers followed out of reverence for tradition. It is also partially the result of combining originally distinct legendary journeys, with differing destinations and stages. Another reason however is that earthly geography has little to do with several aspects of the myth, which are concerned with a voyage into a magical realm. Elastic geography is a regular feature of Greek myth in general. There are at least four and perhaps as many as six locations for Mount Olympus. The route and indeed the destination of the Argonauts are similarly cloaked in mystery.

The legend contains, beside its central objectives, many magical themes of great antiquity and clues to archaic elements of Greek religion. Some of the more salient, as they appear in the epic of Apollonius, are noted here.

The epic begins with the arrival of Jason at the court of the usurper, Pelias, in the city of lolcus in Thessaly. This northernmost region of Greece bordered Macedonia to the north; to the west Illyria and Epiros, with the sea to the East. Of the various mythic locations of Mount Olympus, the Classical site was in Thessaly. The inhabitants of the region were notoriously given to magical practices and barbarous incantations. It is thus a suitable starting place for a study of archaic magic in Grecian culture. It is doubly so since, having the sea to the East, the departure of the Argo is from Thessaly towards the Black Sea. This geographically and symbolically puts Classical Greece behind us, and enters the terrain of myth and ancient ritual wherein Goetia is rooted.

King Pelias had dispossessed Jason’s father, and Jason’s return was at the advice of an oracle to seek and claim his inheritance. On the way there he had crossed a flooded river and carried an old woman across, who was