Shamanism for the Age of Science: Awakening the Energy Body - Kenneth Smith 2018

Components of Learning

The Heartbeat of Learning

Regardless of your stage of development, having the basics of learning under your belt is essential in order to consciously awaken. As characterized by working through altered states to discrete altered states to a new baseline, each shift in cohesion represents learning. The more awareness you have integrated, the more you have learned. The greater you plug into the environment, the more awareness you have. And in an infinite world, there is always more.

The heartbeat of learning consists of continually expanding into imagination and then contracting that awareness into practical application. All of the imagination and learning perspectives in this book serve to help you regulate your energy body to permit this form of accelerated learning. As with anything else, you can keep developing these and other techniques to elevate your level of ability.

Components of Learning

The following section provides an overview of a few key aspects of effective learning. They are meant to enhance understanding of cohesional dynamics as they build on the known world while taking into consideration venturing into the unknown. Skills and processes referenced in the previous chapters promote the development of each these behaviors.

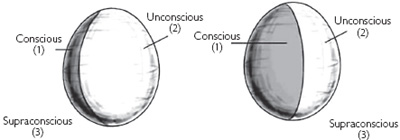

Figure 11.1. Energy Body Learning

From a shamanic perspective, learning and imagination provide a rhythmic process of increasing the known and reducing the unknown portions of the energy body. Understanding that there is an aspect of existence that can never be known—the unknowable—serves to keep the arteries between learning and imagination open and vital.

Memory

In daily use, we relate to memory as consciously recollecting the past. Examining how this occurs, scientific investigation has defined memory as “. . . the way the brain is affected by experience and then subsequently alters its future responses.” Memory therefore creates a hinge to look at how past events affect future behaviors. In like manner, don Juan holds that our experience of the world is based on memory.1 Reality, then, both personal and consensus, is constructed in part from a stream of associated memories that create a pattern, a view of the world. There needs to be continuity of learned relationships in order to make a leap from past events to figuring future responses, and the options for this behavior stem from what has meaning, value, and relevance as these are the forces that collect memories.

In a brain model, continuity of perception results from the formation of neural networks. Repetition of experience and the internal narrative that cements the meaning of experience stabilize these pathways, producing long-term memory. A wide range of associations occur during correlating certain letters to form a word, for example, to how biochemical activity gives rise to cellular interactions and pathways. Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel says this process requires an anatomical change, rendering a more lasting and complex network.2

This hardwired network changes as the web of memory changes and vice versa. It may expand due to new experiences or dissipate from lack of use. Having more contexts from which to derive meaning from new experiences adds to how the brain adapts. Part of this neuroplasticity, says psychiatrist Norman Doige, comes about as the abilities and functions of memory change as a person grows older. Children’s memory carries different qualities than those of adults, for example.3 One might speculate that these types of variances are also found among the stages of awakening, with each new stage reflective of a more enhanced neural network or energetic coherence.

Another portion of these mechanics is that a person can use the same plastic quality of the brain to unlearn their continuity by removing associations that lock memories in place. Remove a piece of the interlocking aspects of an event that gave rise to a memory and the neural network dissipates, thereby changing or eliminating the memory. Likewise, if you can summon a sufficient number of associations, you can restore the entire memory.

In this manner, you can also reshape mind. Just as memory reflects your repetitive behaviors and internal narrative, which give meaning to experience, it conditions perception as to what forms your inventory. Mind is therefore structured in the same manner as neural networks. It then follows that the nature of the network indicates the way mind has been conditioned. Perhaps inventories and neural networks are mirror images.

Possibly even more indicative of the flexibility of memory, imagination can be used to intentionally make changes in the pathways and determine new memories, a purposeful remodeling of networks. This doesn’t mean you changed the event that placed the experience-memory in your neural network; it means you have a new perceived relationship with the continuity of experience, which then alters your narrative, your stream of thoughts about your life. In practice, for instance, you may rearrange facts to establish a new past-to-future continuity and in so doing give yourself a chance to respond more intelligently. Applying this to reality, a consensus view of the world results from people sharing a similar network, and this has the effect of reinforcing specific pathways of perception. Change the network sufficiently and you change reality. It’s a matter of how potential and actual interact. This is a bit of the metaphysics behind the formation of what is deemed to be “real.”

In addition, a person’s affective style influences memory. Candace Pert maintains that emotion is a means of activating a neural circuit throughout the entire body.4 Therefore your emotional stance helps form memory by developing your narrative, the resulting associations, and then the continuity of your reality. Meditation and relaxation promote emotional fluency and therefore the ability to access other states of consciousness.

This brings us back to the location of memory. Most researchers relegate memory to the brain. Reflecting their whole-body approach, Toltec shamans ascribe to a different model and so place it in various places throughout the body. Through centuries of examining memory through seeing, they reached consensus that the brain registers, not determines, what takes place in the physical and energy bodies. Memories associated with specific parts of the body then stimulate certain areas of the brain. Scientific considerations supporting this shamanic perspective are beginning to take root. For example, in addition to Pert’s findings, by relating memory to the extracellular matrix the entirety of the body is involved with memory.5

As Kandel mentions, it is scientifically accepted that different types of memory are relegated to different regions of the brain. For example, peak experiences suspend and stimulate specific brain functions. Also of interest is the Blakeslee’s presentation of a brain-map model where memories initiating behavior of learned muscle responses emanate from brain maps. While the map represents functions, the brain remains the controlling focus. Yet another consideration Lipton puts forth is the emerging evidence indicating that cells use their own style of memory for intelligent decisions to help ensure their survival.6 It is as though each model, scientific and shamanic, mirrors the other yet with first cause originating either in the brain or the body. After all, since each approach forms and is formed by memory, each has entrained to a different narrative and continuity. Taking in all of this, shamans could simply be wrong, or perhaps science has not yet developed a model that permits different insight. And perhaps factual only relates to a model, not necessarily to an actual condition.

These models are also similar in terms of the formation of neural networks and cohesion. Experience combined with repetition of narrative creates energetic structures in the brain or in the energy body and the ability to remodel networks or cohesion seems evident. From a biophysics perspective, it is possible that shamans first measure the behavior of energy and how that translates to anatomy and physiology whereas scientists usually seek first cause by studying physiology.

In that neural networks and cohesion form in similar manner and have similar effects, they provide useful models to study each other. A network becomes permanent, for instance, the more you develop a certain skill or viewpoint. This also reflects a cohesional shift: the more extensive and interrelated coherence, the more extensive the baseline. The more memory networks you have, the more you step toward a new stage of awakening. In each model, the breadth and depth of the respective network marks the difference among individual abilities as well as overall ontological condition, or total-life focus.

In addition, Tart addresses the phenomenon of state-specific memory.7 Experiences in ASCs or d-ASCs, for example, illustrate this as you must return to the constellation of perception associated with an altered state in order to remember it. To bring the event to a conscious working memory, you need sufficient repetition of the memory, which enables it to be easily referenced as you’ve formed the required neural networks.

Looking at this from the energy body, remembering means you have returned your assemblage point to the place associated with the experience; you have shifted cohesion to the coherence storing the memory. This applies to ordinary and state-specific memory. For instance, you may not remember having had an altered state until your cohesion expands to where it fully incorporates the experience associated with the memory, until you have the wherewithal to manage your ASC and place it in a new baseline. For all types of memory, the recapitulation provides the intent to consciously remember in order to review and release the energetic fixations.8

Shamanism also puts forth quite another reference, another set of associations, for the relationship between memory and experience. In terms of multidimensional reality, a new memory could mean you’ve actually jumped realities into another stream of experience. Your memory changed because in this new continuity the event didn’t occur in the same manner as it did in your prior memory. The event is materially different and is part of a continuity matching your new memory. Another way of saying this is that you latched onto a different emanation. When you have either memory, it is because you have aligned with the energy emanation that carries the respective experience.9Seeing provides a means to assess the nature of emanations as it allows direct perception of the flow of energy. From this point, managing memory takes on new features. Tapping different emanations may produce memories of other dimensions, of heretofore unconscious healing practices that are naturally embedded in the energy body, or of a long-forgotten event brought forward in time by the recapitulation.

Just as there are various forms of intelligence, there are aptitudes relating to memory. These often influence one’s choice of professional path as it connects to natural ability, meaning, value, and relevance. One person might have excellent recall of textbook instruction, while another is fluent with science fiction concepts, and yet another adept with remembering nuances of people. One person’s bent of memory might lead to a synthesis of aspects of time that accounts for teleportation to how psi functions to speed of cellular communication, while another person invents a fuel-saving automobile engine, while yet another person produces Broadway plays.

From this brief overview, it is evident that memory plays various roles in our lives and affects learning in ways far beyond the single act of recalling the past. What, then, can be done to work with memory as applied to your energy body? The following techniques offer a guideline. If needed, please refer to previous sections of this book where they are presented in more detail.

1. In general, deautomatization suspends associations and perhaps complete neural or cohesional networks. Depending on the specific technique, certain areas of the brain and energy body may be activated or held in abeyance. This allows you to deliberately intend changes to bring about a range of behaviors such as changing a specific memory to how you use memory to entering new meanings about memory.

2. Stopping your internal dialogue is ideal for interrupting your narrative. Upon examination, you’ll discover you have a storyline for all your activities. If you continually carry around everything you find meaningful, you limit learning. Step into fresh, open, unbiased perception from time to time. This is the center of being.

3. To lessen the hold memories have on your cohesion and on your neural networks, recapitulate the events forming your life. During the recapitulation you deliberately recall events, and often events long forgotten unexpectedly return to conscious memory. The exercise then allows you to discharge the energy holding together the cohesion without losing the memory or learning.

4. To encourage a new set of relationships, meaning, and continuity forge your path with heart.

5. Rigidly holding onto memories inhibits new awareness. This narrative prevents formation of new pathways, new cohesions. Dishabituation provides for new experience and new energetic structures to form. When you base future behavior solely on past events, you block imagination and the ability to respond to the world in new ways. In this manner, memory can be managed rather than allowing it to remove the remembrance that we are part of infinity and live in a multidimensional world.

Intelligence

In his book, The Genius Within, neurosurgeon Frank Vertosick places intelligence beyond commonplace memory, saying it is “. . . the general ability to store past experience and to use that acquired knowledge to solve future problems.”10 In How the Mind Works, cognitive science professor Steven Pinker presents it as “. . . the ability to attain goals in the face of obstacles by means of decisions based on rational (truthobeying) rules.”11 Both orientations pose a range of questions: How do we define a goal? Is intelligence a biological imperative or an aesthetic decision? What is rational? Is it intellectual alone or can we also apply it to obeying rules through the use of intuition or seeing? And what is the method for determining “truth”?

Vertosick points out that some bacteria possess intelligence since they defeat antibiotics as they surge forward and evolve into highly resistant strains. They don’t use mental intelligence; chemistry has been their language for millions of years producing a highly successful way of solving their life-threatening problem of antibiotics. There has to be some form of “truth-obeying” rules on which the bacteria base their form of decisions.12

From a similar principle, animals overcome obstacles to successfully migrate or to alertly watch over their own kind as they take shifts in eating and acting as sentry. According to the definition of mind presented earlier, animals don’t possess mind as they don’t self-reflect in such a manner as to create inventories. They abide by a natural intelligence that is not rational in the ordinary use of the term, yet is rational as they behave in line with some type of truth-obeying rules that can be highly intelligent. Both bacteria and animals act rationally in that their behavior works, not that it reflects intellectual logic. To therefore relegate intelligence to intellectual properties removes humans from the environment, diminishes awareness, and estranges us from the greater order of life.

As often considered, intelligence also pertains to fluency of insight regarding the prevailing model, be it of a laboratory experiment or a worldview. There are different facets to this. For instance, the ability to form detailed constructs from an already established model is beneficial. Doing so reflects a standard view of the role and value of memory. A person might then provide a more elaborate, scientific picture of cellular behavior. There also exists the ability to take existing pieces of a model, or different models, and develop new context and applications, which indicates creativity and learning. At the same time, relegating rote recall of facts, no matter how sophisticated, as being a pinnacle of intelligence undercuts efforts to extend consciousness into new areas as it enhances the status quo rather than extending awareness into imagination to foster leaps of learning.

In addition, speed of processing information is often hooked to defining intelligence, as with IQ measurement where this is reflected in the score. In resolving a crisis, speed helps. This may translate to life or death. Rapid learning is a sight to behold. But speed is also relative to the method being applied to achieving a goal, and quickness doesn’t always equate with the ability to produce optimum response. For instance, a person may process information so quickly, he or she misses data that should be included but is not part of their inventory. The degree of objectivity summoned also plays a role in the quality of their perceptions.

Or, for another example, one person could come up with an excellent solution in two minutes only to be trumped by another person who has meditated for ten hours and then delivers an answer that formed suddenly, without mental deliberation, in the instant prior to ending meditation. Yet another person could philosophically ponder and, by relating the situation to a wide range of possibilities derived from experience and memory, come up with the most intelligent answer. Furthermore, acting too quickly may produce detrimental consequences such as from inadequately measuring ethics or not fully determining the long-ranging effects on the environment of a technological invention. Speed might solidify an ignorant response and reflect lack of intelligence.

At the same time, as speed of processing can apply to any form of intelligence, it does stand as a legitimate measure. But what is being measured and to what end? What expresses more intelligence: speed of mental processing or speed in utilizing imagination? Processing therefore needs to be based on natural ability of the whole person. Forced speed, an arbitrary requirement to perform quickly ingrained in many cultures, prevents being, which represents a natural relationship with the world and carries its own timing. Owning up to and abiding by an innate trait is intelligent behavior and shouldn’t be tagged solely to speed. We need, then, to question the viability and value of measuring intelligence rather than allowing it to unfold. How this relates to an individual’s style of what information is processed and in what order are part of the consideration. This brings to bear ontological intelligence, which finds expression though a path with heart. If limiting definitions cause us to overlook something vital to our well-being, individually or collectively, then it isn’t intelligent behavior.

Having said this, speed of learning is essential to navigate the stages of awakening, to actually find yourself in the artisan’s domain before you run out of time in life. Perhaps time and the ability to manage time, including personal timing, should be examined as a distinct form of human intelligence. To refine ontological timing, you might decide to alter your normal rate of walking. For some, it may also seem like you’re not processing events quickly enough to keep up with others and you may be viewed as embracing a diminution of intelligence. Fear of being ostracized may then add pressure to conform, resulting in estrangement from self.

In addition, timing is principally measured by feeling, which again brings to bear emotional intelligence. Using Valerie Hunt’s consideration that emotions organize the mind, then a person who is not as fast with mental processing as another but quite adept with emotional processing of information—something that is not generally measured in contemporary life—should, in these terms, be the more intelligent. From this angle, the intellect only processes a portion of what emotional intelligence is capable of processing. This notion alone reshapes how we would view intelligence.

Another type of intelligence to consider placing in textbooks is multidimensional, or the ability to relate many dimensions to each other and simultaneously to the problem at hand. You may also think of this as spherical, or full-bodied, intelligence, characterized by the ability to synthesize seemingly disparate pieces of information. The Free Perception exercise in the previous chapter serves as an example of weighing opposite concepts to arrive at new insight. Developing this ability might require venturing into other dimensions as doing so provides experience for enhancing memory and a wider perspective to assess problems and goals. You might then process and synthesize information better, if not faster, to arrive at an imaginative solution.

Doige says novel environments trigger neurogenesis, or rejuvenation of the brain.13 By exploring areas of perception and consciousness other than those of consensus reality, you stimulate not only your energy body but also neural pathways, which augments ability. This is another indication that cohesion and neural networks correspond and may influence each other. Through stimulation both can rebuild and even expand, and the manner in which this occurs illustrates how one model helps make sense of the other.

As with any form of intelligence, it’s all for the better if someone has intellectual prowess. But is it being used to awaken the entire energy body or just a narrow range of functions? As with Tart’s view of memory, intelligence needs to be assessed as a state-specific phenomenon, something that cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Intelligence, like other behaviors, functions from cohesion. The ability to manage cohesion changes the landscape of intelligence, of potential, of possibility. Doing so indicates the ability to learn, perhaps the defining aspect of intelligence.

From an energy body perspective, the basis of intelligence is cohesion, the general determinant of awareness and problem-solving ability. Cohesion forms through learning and imagination, and thus the degree of awareness relates to the breadth and depth of cohesion. The nature of cohesion also corresponds with problem-solving ability. Through understanding and managing the intelligence of the energy body, you awaken multiple intelligences such as those outlined here and in chapter eight, with all of these influences combining to enhance ontological intelligence.

Cohesional intelligence spins these considerations anew; new doors to discovery abound. All said and done, awakening your energy body leads to your natural intelligences, including the best way to implement them—keeping in mind that the way you use what you have also relates to intelligence. The cumulative effect of employing these intelligences is that of bringing yourself further to life, allowing your potential to be realized, and enabling you to experience a deeper, more meaningful life.

A few perspectives for grooming intelligence include:

1. Use memory for reference, not for strict maintenance of your reality. Memory provides a foundation for continuity and continuity hardwires memory. A fixed continuity means you’ve a conditional energy field and the aim is to work through such fields to a natural field of being. At this point, continuity takes on completely different meaning.

2. Experience, experience, experience . . . as many aspects of life as you can. As outlined above, experience feeds your brain, energy body, and all of their systems.

3. Relate your experiences to each other and to others’ experiences. Draw diagrams of these relationships if doing so makes this more effective.

4. Study energy body mechanics. Learn the ins and outs of cohesion as all forms of intelligence are governed by their respective cohesions.

5. Try to sense connecting with the environment and the related rate of processing information based on being focused in your thoughts and head or in your feelings and entire body.

6. Don’t be concerned with looking completely ignorant on a regular basis. Allow yourself time to absorb and process information without feeling you have to appear “in the know.” Over time, this contributes to expanding your cohesion and knowledge.

Objectivity

Objectivity provides both ballast and rudder for inquiry. It centers you, enabling a means to better navigate your life. It is also an effect of learning. As professionals learn more about their specialty, for example, their objectivity is enhanced as they obtain a wider angle with which to measure. This could lead to fundamentalism, though, as you might settle into the wider picture and unwittingly get lost by constantly cross-referencing the same thoughts and feelings, thereby preventing further exploration and learning. Objectivity requires mental and emotional intelligence devoid of reactivity caused by excessive allegiance to a specific cohesion.

The same applies to consciousness development: the more you develop ontologically, the more objective you are about life in general. You deal with situations as they are, rather than what you imagine or want them to be; you bring potential to what is actual rather than ignore the actual. Then again, you stand to lose yourself in your imaginative adventures, as real as they might appear, and never enjoy the grander scheme brought about by awakening your core to infinity. This is the difference between a life lived in terms of social dictates, or lived in line with the way you were created.

In dealing with these ins and outs, objectivity provides a significant influence in forming cohesion as it reflects the need for accuracy in building an inventory. With diligence, and the secure relationships among data provided by logic, cohesion’s baseline incorporates core awareness. Projection and reflection are thereby minimized, and ethical balance and overall harmony automatically begin to enter consciousness and behavior.

As Tart points out, a great discovery of our time is that what seems to be objective observation actually reflects the biases of the experimenter. Science, often considered a bastion of objectivity, is a social enterprise. It yields to logic from group consensus. This presents both blessing and curse. The nature of it requires that scientific data be available to the group, especially to qualified investigators who assess and respond. When an experiment can be replicated time and again, the group accepts the results and we have another benchmark to measure novel studies.14 And so knowledge moves forward.

The downside is that new data is often expertly refuted as it doesn’t fit with established models. While the cooperative nature of research supports objectivity, it is easy to get lost in current knowledge as it becomes interpretation based on what is thought to be possible and is therefore not at all objective. In a study of creativity, for example, psychiatrist Nancy Andreasen points out that while observations may be objective, the results may be subjective.15 A conclusion from arranging facts in a certain order might not be objective; it might result from biased memory or personal desire.

Illustrating this energetic, there is a contingent of people who propose the earth is hollow, possibly providing an inhabitable environment. Contradicted by all measures of modern investigation, this thinking has been relegated to pseudoscience.16 Looking at this from another angle, the proponents of this theory might be sensing that the backdrop of the physical world is not comprised of physical matter but of energy. Without having context for this form of sensing, their perceptions of an extradimensional environment gave rise to an interpretation that the physical earth is hollow. That is, while they extended their awareness and sensed something different (the absence of solid earth), their interpretation could have been influenced by a lack of context, a diminished awareness of cornerstones and quantum physics, for instance. The initial perceptions may be objective; the interpretation is not. Their perceptions legitimately stand to extend the current worldview, but then fall into disrepute due to the interpretations. The seed of knowledge never bore fruit.

William Byers, author of How Mathematicians Think, makes an interesting case that further illuminates this dynamic. He says that while logic provides stability and common reference, math transcends logic. It exists beyond a collection of answers and requires [italics mine] a subjective component. This leads to understanding [italics his]. Understanding requires intuition. This sets the stage for the logic that stabilizes a point of view to fall to the wayside if intuition contradicts factual conclusions. This ambiguity, states Byers, opens the door to imagination, revealing “. . . the nature of reality itself, or at least the manner in which the human mind interacts with the natural world.” Therefore, objectivity is at once a necessary determinant for accumulating knowledge and also a mirage.17

In measuring reality, all interpretations are skewed to the reflections of human perception and limited by anatomy. Uniformity and cohesion determine the range of potential, for instance, yet add measure to the existing picture of our anatomy. Professor Wallace tells us that when exploring consciousness we need to “. . . identify the metaphysical doctrine that underlies and structures virtually all contemporary scientific research.” The foundation of this doctrine, he says, is that of scientific materialism, which, in part, consists of objectivism, reductionism, and closure. Therefore, while scientific knowledge and objective knowledge are often synonymous, the results of such inquiry reveal “rules of the game,” not necessarily absolute truth.18

The complexity of this book results from bringing to bear several disciplines to a common focus. It serves as an example of the detail and intricacy of energy body processes. There are many influences that go into building cohesion and we are not conscious of the vast majority. We then unwittingly behave from significant bias as we bend our perceptions of the world to suit ourselves.

Understanding the labyrinth of objectivity engenders the ability to employ it. Applying objectivity to this work, for instance, we need to view the energy body as simultaneously independent of the environment but also enmeshed within, and governed by, it. The energy body can move about and assess situations through subject-object relationships, yet it exists firmly as integral with the environment. Managing this internal-external referencing offers challenges. Projection and reflection rear up at any time, desires cast one against the rocky shore, and accurate orientation often seems out of reach.

Metaphysical philosophies constructively use such forces of perception. By understanding that the energy body intimately connects with the world, for example, the perception of separateness that non-attachment instills contributes to balanced objectivity. This presents the high side of forming subject-object relationships. With these systems, you may consciously enter environments conducive to learning. The stages of awakening provide an outline of what to look for, a path with heart offers stability, and timing generates the grace to navigate your circumstances. You then obtain the widest, most accurate viewpoint, experience a greater world, and hopefully live a better life. How is this not intelligent?

Listening

Listening provides a key ingredient for any aspect of learning. If you’re constantly telling yourself what the world is like, you can’t listen to another line of thought. Effective listening instills openness without prejudice. You allow interpretations to come to your awareness naturally rather than engage ongoing formulation. A fundamentalist acts and talks as an expert, yet doesn’t acquire new information. Cohesion then remains not only conditional but also static.

Daniel Goleman provides categories of listening such as defensive and active. Often listening takes on a defensive quality, such as exhibited during an argument, and so nothing is gained and often much is lost as one conditional field collides with another and the people involved hear only what they want to hear. Goleman considers empathy—hearing the feelings behind the words—to be the “most powerful form of defensive listening.” He cites active listening as being when one person provides feedback to the other and then listens anew in an effort not to make assumptions or jump to conclusions, and thereby garner at least a measure of objectivity.19

In broad application, to listen means to “pay attention.”20 In this light, listening is a deautomatization procedure that utilizes as many modes of perception as possible. For example, to see—listening to energy—awareness must be open in order to connect with the world free of bias; otherwise, seeing remains latent. Meditation is also listening, as is the general use of intuition, and as is feeling the intent that carries words spoken or written.

Self-guidance

If learning necessitates stepping outside consensus, then relying on your own resources is imperative. Without doing so, you remain within group cohesion, which dampens imagination. To navigate life and learning, self-guidance stems from impressions, feelings, visions, and physical sensations that let you know what is going on. Just like learning a written language, you can develop a rich means of communication. To help you begin:

1. Initially, find a time and place where you’ll be uninterrupted. As you develop self-guidance, apply it to situations where you will be interrupted and where you use it in group environments.

2. Feel for any sensations in your body: tingling, pressure, pain. Place your attention in that area. Allow the sensation to expand within your full attention. Within your awareness, perceive what represents, why it is there.

3. Use as many forms of communication as possible to “hear” the answer. You might perceive images, sounds, or kinesthetic sensations.

4. Throughout the day, assess your feelings. While you’re out for a walk, you might feel like heading in a certain direction. While talking with your partner, you might feel like doing something in particular. This may also help facilitate brainstorming sessions at work.

5. Play with these thoughts, feelings, and images. Notice if symbols intuitively mean something to you. Try them out as guidance by using them as environmental indications.

6. Study and test your guidance. In time, you’ll learn what to trust. In essence, sure-footed internal guidance comes from silent knowledge.

Silent Knowledge

Silent knowledge results from connecting with and seeing energy fields, not through reason and talking. It originates from forging a link with intent.21 Emanations embody intent, which means intent ranges from the personal to the cosmological. There are those that bring individual energy bodies to life and those that create universes.

We all have silent knowledge, says don Juan, a complete knowledge of our condition. He adds that once a person learns of this possibility, it is a matter of awakening to it, of removing the natural barriers to this birthright.22 Practices and procedures such as outlined in this book, and those presented in other traditions, are sleight-of-hand techniques to help usher you to silent knowledge. They serve as necessary artifices to achieve a completely different relationship with yourself and the environment. This new awareness can’t be outlined as it is a matter of silent knowledge, and represents your individual pattern of energy and how that connects with and expresses itself among all the other energies.

Managing flow requires this form of awareness. Flow feels like a stream of energy running through you. Try to cling to it and it disappears. Allow it freedom and it guides you toward fulfilling your nature. The sensing of this rarified energy intensifies the more you connect with core. From this orientation, you learn quietly and abundantly.

You groom silent knowledge through exploring the cornerstones, intent, and new relationships with the world. You learn to approach life from a different reference, that of innate ability rather than deferring to a description of the world. Potential abounds. Taking this to a professional level requires employing the same energy management skills that placed you on the threshold of silent knowledge. Applying yourself is a matter of personal responsibility. The basics of energy management provide the foundation for such a quest.

A Learning Posture

Here is a summary of behaviors that promote learning. Combined they offer a posture to help you walk attentively and purposefully throughout the course of a day, no matter the environment.

Maintain cool effort. Don’t bash your head into walls. Don’t try to force the world into compliance with your wishes. Learn what the world is. Don’t arbitrarily work according to another person’s timetable. Have a little fun finding out the natural rhythms of your life. Then relax, be patient, and let your energy body breathe. Learn to love to learn. Have a “romance with knowledge,” as don Juan puts it.23

Exercise a high level of inquiry. Stay open and flexible. Keep asking questions. Don’t settle for an answer when your body yearns for more. Look at the evidence, at what occurred, at what is . . . not what others say is so. Use all of your experience and let your knowledge be rendered obsolete when appropriate. Use all the deautomatization skills you can at any time you can. As philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer says, “The contemplation and observation of everything actual, as soon as it presents something new to the observer, is more instructive than all reading and hearing about it.”24

Sustain the pursuit of objectivity. By applying the lessons of cohesion, we know that anything we perceive is simultaneously real and illusory: real from its own vantage point, illusory (potential) from another assemblage point position. We have objectively-defined anatomical hardware, yet the experience it provides is subjective. Quantum theory tells us that results are influenced by the observer, which makes everything subjective. At the same time, this awareness indicates objectivity. You might say objectivity is what keeps you from lying to yourself. It is what allows you to accurately observe and assess yourself, others, and the world. Interpret events based on a commitment for accuracy rather than on personal desire.

Acknowledge complete responsibility. Do so for all your behavior, for all that you perceive, and for everything that results from your inquiries and adventures. Claim what you know in a way that accents continued learning. Rather than constantly emphasize, “I know,” exercise the open switch to listen and observe without losing sense with what you do know, where you’re going, and how it all fits.

Cultivate ever-expanding context. Effective learning requires having context with which to apply experience. You can partake of an exquisitely rich learning environment yet not be able to take advantage of it, as you don’t know what it represents or what to do with it. Seeing without knowing of this mode of perception provides an example. Odds are that most people will dismiss spontaneous seeing as an anomaly since they don’t have context regarding it, and so the experience may be relegated to a state-specific memory. In this instance, context includes such things as knowing of the cornerstones, how they work, their range of perception, how they relate to exploring the world at large, and then all of these specifically focused on seeing. The same applies to ordinary situations. Could a cowboy of the 1800s know what to do with an automobile, or could a person never exposed to information technology know what a computer represents, let alone what to do with it? Context also represents a conditional field and therefore learning carries the added ingredient of the continual expansion of cohesion and context.

Learn for mastery. Prepare yourself to take your learning into new areas, some of which may cause unwelcome comments from those who consider themselves authorities. Balance and relax within and without. Minimize reflection and projection. Release any hold the new cohesion has on you to avoid fundamentalism and continue learning. The more cornerstones you use, the more information you have to ply into expanding cohesions. The more you listen and remain open to learning, the more skill you employ. Learning in such a manner harnesses an intentional process involving ever-expanding abilities.

This posture relates directly to an energy body posture. When you try to determine your life by reason alone, you warp cohesional energies. Thought is but a fraction of the resources available to assess learning and life. At the same time, a similar dynamic may occur when you’ve activated will, meaning you have learned to engage life with your complete energy body. If you try to command your life with will, you again distort internal energies as well as your relationship with the world. A viable posture is to center yourself in openness and then direct your specific actions with intent, a posture leading to being. This grants you the ability to pay attention to the moment, remain open to new information, and yet remain sufficiently closed to sustain focus and accomplish your goals.