The Big Book of Runes and Rune Magic: How to Interpret Runes, Rune Lore, and the Art of Runecasting - Edred Thorsson 2018

Elder Runes

Historical Lore

(TO 800 C.E.)

This chapter is intended to provide the runer with a basic outline of runic history and development from the oldest times to around 800 C.E. (or the beginning of the Viking Age) and includes a section on the Old English and Frisian traditions that continue beyond that time frame. It is necessary for anyone entering upon the esoteric study of the runes to have a fundamental notion of the historical context of the tradition. The discussion here will provide the foundation for this task; independent readings and studies must build the larger edifice. The majority of the information contained in this first part of the book has been gleaned from scholarly works on runology (see Bibliography). The exoteric facts and interpretations contained in these pages will serve the runer well as an introduction to the wondrous world of rune wisdom developed in later parts of the book.

The Word Rune

The most common definition for the word rune is “one of the letters of an alphabet used by ancient Germanic peoples.” This definition is the result of a long historical development, the entirety of which we must come to know before we can see how incomplete such a definition is. Actually, these “letters” are much more than signs used to represent the sounds of a language. They are in fact actual mysteries, the actual “secrets of the universe,” as one who studies them long and hard enough will learn.

Rune as a word is only found in the Germanic and Celtic languages. Its etymology is somewhat uncertain. There are, however, two possible etymologies: (1) from Proto-Indo-European *reu- (to roar and to whisper), which would connect it with the vocal performance of magical incantations, and (2) from Proto-Indo-European *gwor-w-on-, which would connect it to the Greek and Old Indic gods Ouranos and Varuna, respectively, giving the meaning of “magical binding.” This is also an attribute of Odin. The word may have had the essential meaning of “mystery” from the beginning.

In any case, a Germanic and Celtic root *runo- can be established, from which it developed in the various Germanic dialects. That the word is very archaic in its technical sense is clear from its universal attribution with a rich meaning. The root is found in every major Germanic dialect (see table 1.1). What is made clear from the evidence of this table is that “rune” is an ancient, indigenous term and that the oldest meaning was in the realm of the abstract concept (mystery), not as a concrete sign (letter). The definition “letter” is strictly secondary, and the primary meaning must be “mystery.”

This root is also found in the Celtic languages, where we find Old Irish rūn (mystery or secret) and Middle Welsh rhin (mystery). Some people have argued that the root was borrowed from Celtic into Germanic; however, more have argued the reverse because the Germanic usages are more vigorous, widespread, and richer in meaning. Another possibility is that it is a root shared by the two Indo-European dialects and that there is no real question of borrowing in the strict sense. Perhaps the term also was borrowed into Finnish from Germanic in the form runo (a song, a canto of the Kalevala), but the Finnish word may actually come from another Germanic word meaning “row” or “series.”

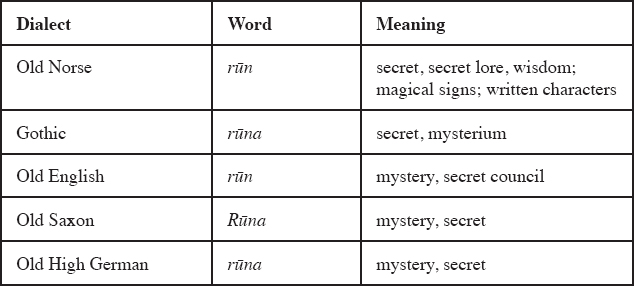

Table 1.1. Germanic rune definition.

Although the word is clearly of common Germanic stock, the actual word in modern English is not a direct descendant from the Old English rūn but was borrowed from late scholarly (seventeenth-century) Latin—runa (adjective, runicus)—which in turn was borrowed from the Scandinavian languages.

The Odian definition of rune is complex and is based on the oldest underlying meaning of the word—a mystery, archetypal secret lore. These are the impersonal patterns that underlie the substance/nonsubstance of the multiverse and that constitute its being/nonbeing. Each of these runes also may be analyzed on at least three levels:

· Form (ideograph and phonetic value)

· Idea (symbolic content)

· Number (dynamic nature, revealing relationships to the other runes)

With the runes, as with their Teacher, Odin, all things may be identified—and may be negated. Therefore, any definition that makes use of “profane” language must remain inadequate and incomplete.

Throughout this book, when the word rune is used, it should be considered in this complex light; whereas the terms runestave, or simple stave, will be used in discussions of them as physical letters or signs.

Early Runic History

The systematic use of runestaves dates from at least 50 C.E. (the approximate date of the Meldorf brooch) to the present. However, the underlying traditional and hidden framework on which the system was constructed cannot be discussed in purely historical terms—it is ahistorical.

Essentially, the history of the runic system spans four epochs: (1) the elder period, from the first century C.E. to about 800 C.E.; (2) the younger period, which takes us to about 1100 (these two periods are expressions of unified runic traditions bound in a coherent symbology); (3) the middle period, which is long and disparate and which witnessed the decay of the external tradition and its submersion into the unconscious; and finally, (4) the periods of rebirth. Although the use of runes continued in an unbroken (but badly damaged) tradition in remote areas of Scandinavia, most of the deep-level runework took place in revivalist schools after about 1600.

It may be argued that a historical study is actually unnecessary or even detrimental for those who wish to plumb the depths of that timeless, ahistorical, archetypal reality of the runes themselves. But such an argument would have its drawbacks. Accurate historical knowledge is necessary because conscious tools are needed for the rebirth of the runes from the unconscious realms; the modern runic investigator must know the origins of the various structures that come into contact with the conscious mind. Only in this context can the rebirth occur in a fertile field of growth. For this to take place, the runer must have a firm grasp on the history of the runic tradition. For without the roots the branches will wither and die. In addition, the analytical observation and rational interpretation of objective data (in this case the historical runic tradition) is fundamental to the development of the whole runemaster and vitki. If a system is not rooted in an objective tradition, many erroneous elements can more easily find their way into the thinking process of the practitioner. Clarity and precision are valuable tools for inner development.

Runic Origins

As the runes (mysteries) are ahistorical, they must also be without ultimate origin—they are timeless. When we speak of runic origins, we are more narrowly concerned with the origins of the traditions of the futhark stave system. The questions of archetypal runic origins will be taken up later on. The runes may indeed be said to have passed through many doors on the way to our perceptions of them and to have undergone many “points of origin” in the worlds.

There are several theories on the historical origins of the futhark system and its use as a mode of writing for the Germanic dialects. These are essentially four in number: the Latin theory, the Greek theory, the North-Italic (or Etruscan) theory, and the indigenous theory. Various scholars over the years have subscribed to one or the other of these theories; more recently a reasonable synthesis has been approached, but it is still an area of academic controversy.

The Latin or Roman theory was first stated scientifically by L. F. A. Wimmer in 1874. Those who adhere to this hypothesis generally believe that as the Germanic peoples came into closer contact with Roman culture (beginning as early as the second century B.C.E. with the invasion of the Cimbri and Teutones from Jutland), along the Danube (at Carnuntum) and the Rhine (at Cologne, Trier, etc.), the Roman alphabet was adapted and put to use by the Germans. Trade routes would have been the means by which the system quickly spread from the southern region to Scandinavia and from there to the east. This latter step is necessary because the oldest evidence for the futhark is not found near the Roman limes and spheres of influence but rather in the distant northern and eastern reaches of Germania. The idea of trade routes poses no real problem to this theory because such routes were well established from even more remote times. The Mycenaean tombs in present-day Greece (ca. 1400—1150 B.C.E.) contain amber from the Baltic and from Jutland, for example. More recently, Erik Moltke has theorized that the futhark originated in the Danish region and was based on the Roman alphabet.

This theory still holds a number of adherents, and some aspects of it, which we will discuss later, show signs of future importance. In any case, the influence of the cultural elements brought to the borderlands of the Germanic peoples by the Romans cannot be discounted in any question of influence during the period between approximately 200 B.C.E. and 400 C.E.

It must be kept in mind when discussing these theories that we are restricted to questions of the origin of the idea of writing with a phonetic system (alphabet) among the Germanic peoples in connection with the runic tradition, and not with the genesis of the underlying system or tradition itself.

The Greek theory, first put forward by Sophus Bugge in 1899, looks more to the east for the origins of this writing system. In this hypothesis it is thought that the Goths adapted a version of the Greek cursive script during a period of contact with Hellenic culture along the Black Sea, from where it was transmitted back to the Scandinavian homeland of the Goths. There is, however, a major problem with this theory because the period of Gothic Greek contact in question could not have started before about 200 C.E., and the oldest runic inscriptions date from well before that time. For this reason most scholars have long since abandoned this hypothesis. The only way to save it is to prove a much earlier, as yet undocumented connection between the two cultures in question. More research needs to be done in this area. Also, it is probable that Hellenistic ideas, even if they played no role in runic origins, may have had a significant part in the formation of some elements of the traditional system.

The North-Italic or Etruscan theory was first proposed by C. J. S. Marstrander in 1928 and was subsequently modified and furthered by Wolfgang Krause, among others, in 1937. Historically, this hypothesis supposes that Germanic peoples living in the Alps adopted the North-Italic script at a relatively early date—perhaps as early as 300 B.C.E.—when the Cimbri came into contact with it and passed it on to the powerful Suevi (or Suebi), from whom it quickly spread up the Rhine and along the coast of the North Sea to Jutland and beyond. There can be no historical objections to the plausibility of this scenario, except for the fact that the initial contact came some three to four hundred years before we have any record of actual runic inscriptions.

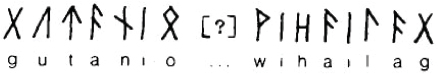

As a matter of fact, there is an example of Germanic language written in the North-Italic alphabet—the famous helmet of Negau (from ca. 300 B.C.E.). The inscription may be read from right to left in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Inscription on the helm of Negau.

The inscription may be read in words Harigasti teiwai . . . and translated “to the god Harigast (Odin),” or “Harigastiz [and] Teiwaz!” In any case the root meanings of the first two words of the inscription are clear. Hari-gastiz (the guest of the army) and Teiwaz (the god Tyr). In later times, it would be normal to expect Odin to be identified by a nickname of this type, and we may well have an early example of it here. Also, this would be an early proof of the ancient pairing of the two Germanic sovereign deities (see chapter 13).

As can be seen from the Negau inscription, the scripts in question bear many close formal correspondences to the runestaves; however, some phonetic values would have to have been transferred. No one Etruscan alphabet forms a clear model for the entire futhark. An unfortunate footnote to runic history has recently been added by a certain occult writer who in two books has represented a version of the Etruscan script as “the runic alphabet.” This has perhaps led to some confusion among those attempting to unravel runic mysteries.

The idea that the runes are a purely indigenous Germanic script originated in the late nineteenth century and gained great popularity in National Socialist Germany. This theory states that the runes are a primordial Germanic invention and that they are even the basis for the Phoenician and Greek alphabets. This hypothesis cannot be substantiated because the oldest runic inscriptions date from the first century C.E. And the oldest Phoenician ones date from the thirteenth and twelfth centuries B.C.E. When this theory was first expounded by R. M. Meyer in 1896, the runes were seen as an originally ideographic (the misnomer used was “hieroglyphic”) system of writing that then developed into an alphabetic system acrophonetically (i.e., based on the first sound of the names attached to the ideograph). One aspect of this is probably correct: the Germanic peoples seem to have had an ideographic system, but it does not appear to have been used as a writing system, and it is here that the indigenous theory goes astray. It is possible that the ideographic system influenced the choice of runestave shapes and sound values.

From the available physical evidence it is most reasonable to conclude that the runestave system is the result of a complex development in which both indigenous ideographs and symbol systems and the alphabetic writing systems of the Mediterranean played significant roles. The ideographs were probably the forerunners of the runestaves (hence the unique rune names), and the prototype of the runic system (order, number, etc.) is probably also to be found in some native magical symbology.

One piece of possible evidence we have for the existence of a pre-runic symbol system is the report of Tacitus in chapter 10 of his Germania (ca. 98 C.E.), where he mentions certain notae (signs) carved on strips of wood in the divinatory rites of the Germans. Although the recent discovery of the Meldorf brooch has pushed back the date of the oldest runic inscription to a time before Tacitus wrote the Germania, these still could have been some symbol system other than the futhark proper. In any case, it is fairly certain that the idea of using such things as a writing system, as well as the influence governing the choice of certain signs to represent specific sounds, was an influence from the southern cultures.

In the end it is most likely that the runes originated in the Latin script. The amount of economic and cultural exchange between Rome and Germania was far more vigorous than is often assumed. What is most interesting about the whole process is that the Germanic people did not just accept the Latin script as a practical way of writing (as other peoples did), but rather they entirely reformed it in a variety of ways to make it part of their own unique and particular worldview. It is this incontestable fact that most obviously leads reasonable people to conclude that there is something mysterious about the runes. They encode esoteric cultural secrets.

This summarizes the story with regard to the exoteric sciences. But what more can be said about the esoteric aspects of runic origins? The runes themselves, as has been said, are without beginning or end; they are eternal patterns in the substance of the multiverse and are omnipresent in all of the worlds. But we can speak of the origin of the runes in human consciousness (and as a matter of fact this is the only point at which we can begin to speak about the “origins” of anything).

For this we turn to the Elder or Poetic Edda and to the holy rune song of the “Hávamál,” stanzas 138 to 165, the so-called “Rúnatals tháttr Ódhins” (see also chapter 8). There, Odin recounts that he hung for nine nights on the World Tree, Yggdrasill, in a form of self-sacrifice. This constitutes the runic initiation of the god Odin: he approaches and sinks into the realm of death in which he receives the secrets, the mysteries of the multiverse—the runes themselves—in a flash of inspiration. He is then able to return from that realm, and now it is his function to teach the runes to certain of his followers in order to bring wider consciousness, wisdom, magic, poetry, and inspiration to the world of Midhgardhr—and to all of the worlds. This is the central work of Odin, the Master of Inspiration.

The etymology of the name Odin gives us the key to this “spiritual” meaning. Odin is derived from Proto-Germanic Wōdh-an-az. Wōdh- is inspired numinous activity or enthusiasm: the -an- infix indicates the one who is master or ruler of something. The -az is simply a grammatical ending. The name is also something interpreted as a pure deification of the spiritual principle of wōdh. See chapter 13 for more details of Odinic theology.

The figure of Odin, like those of the runestaves, stands at the inner door of our conscious/unconscious borderland. Odin is the communicator to the conscious of the contents of the unconscious and supra-conscious, and he/it fills the “space” of all of these faculties. We, as humans, are conscious beings but have a deep need for communication and illumination from the hidden sides of the worlds and ourselves. Odin is the archetype of this deepest aspect of humanity, that which bridges the worlds together in a webwork of mysteries—the runes.

Therefore, in an esoteric sense the runes originate in human consciousness through the archetype of the all-encompassing (whole) god hidden deeply in all his folk. For us the runes are born simultaneously with consciousness. But it must be remembered that the runes themselves are beyond his (and therefore our) total command. Odin can be destroyed, but because of his conscious assumption of the basic pattern of the runic mysteries (in the Yggdrasill initiation) the “destruction” becomes the road to transformation and rebirth.

Age of the Elder Futhark

As mentioned before, the oldest runic inscription yet found is that of the Meldorf brooch (from the west coast of Jutland), which dates from the middle of the first century C.E. From this point on, the runes form a continuous tradition that is to last more than a thousand years, with one major formal transformation coming at approximately midpoint in the history of the great tradition. This is the development of the Younger Futhark from the Elder, beginning as early as the seventh century. But the elder system held on in some conservative enclaves, and its echoes continued to be heard until around 800 C.E., and in hidden traditions beyond that time.

The elder system consists of twenty-four staves arranged in a very specific order (see Table 1 in Appendix I). The only major variations in this order apparently were also a part of the system itself. The thirteenth and fourteenth staves :![]() : and :

: and :![]() : sometimes alternated position; as did the twenty-third and twenty-fourth staves :

: sometimes alternated position; as did the twenty-third and twenty-fourth staves : ![]() : and :

: and : ![]() :. It should be noted that both of these alternations come at the exact middle and end of the row.

:. It should be noted that both of these alternations come at the exact middle and end of the row.

By the year 250 C.E., inscriptions are already found over all of the European territories occupied by the Germanic peoples. This indicates that the spread was systematic throughout hundreds of sociopolitical groups (clans, kindreds, tribes, etc.) and that it probably took place along preexisting networks of cultic traditions. Only about three hundred inscriptions in the Elder Futhark survive. (To this about 250 bracteates with runic stamps can also be added.) This surely represents only a tiny fraction of the total number of inscriptions executed during this ancient period. The vast majority done in perishable materials, such as wood and bone—the most popular materials for the runemaster's craft—have long since decayed. Most of the oldest inscriptions are in metal, and some are quite elaborate and developed. Those on gold objects were mostly melted down in the following centuries.

In the earliest times runestaves were generally carved on mobile objects. For this reason the distribution of the locations where inscriptions have been found tells us little about where they actually were carved. A good illustration of this problem is provided by the bog finds (mostly from around 200 C.E.) on the eastern shore of Jutland and from the Danish archipelago. The objects on which the runes were scratched were sacrificed by the local populace after they had defeated invaders from farther east. It was the invaders who had carved these runes somewhere in present-day Sweden, not the inhabitants of the land where the objects were found. As the situation stands, it seems that before about 200 C.E. the runes were known only in the regions of the modern areas of Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein, southern Sweden (perhaps also on the islands of Öland and Gotland), and southeastern Norway. As the North Germanic and East Germanic peoples spread eastward and southward, they took the runes with them, so that scattered inscriptions have been found in present-day Poland, Russia, Romania, Hungary, and Yugoslavia. The runic tradition remained continuous in Scandinavia until the end of the Middle Ages. One of the most remarkable Scandinavian traditions was that of the bracteates, thin disks of gold stamped with symbolic pictographs and used as amulets, carved between 450 and 550 C.E. in Denmark and southern Sweden (see figure 1.6 on page 15). Two other distinct yet organically related traditions are represented by the Anglo-Frisian runes (used in England and Frisia from ca. 450 to 1100 C.E.) and the South Germanic runes (virtually identical to the North Germanic futhark) used in central and southern Germany (some finds in modern Switzerland and Austria) from approximately 550 to 750 C.E.

Futhark Inscriptions

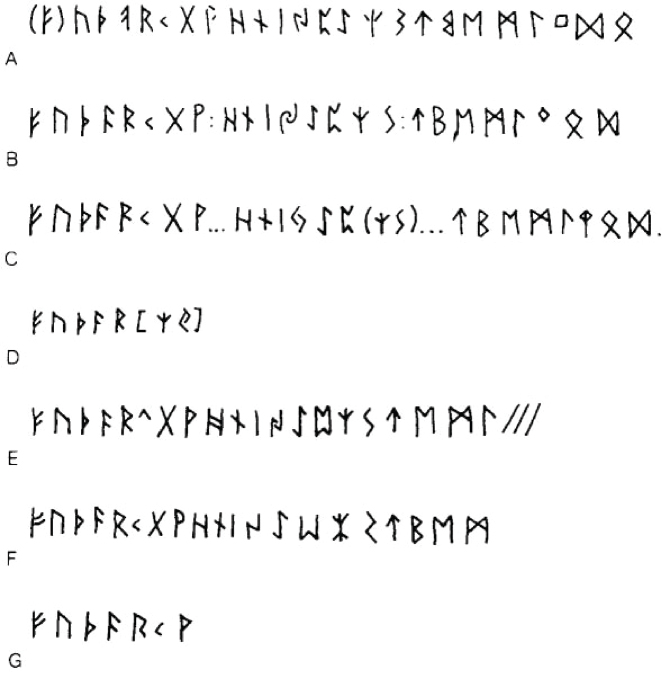

We have seven examples of inscriptions that represent the futhark row, completely or in fragments, from the elder period. They appear in chronological order in figure 1.2. on page 12.

The Kylver stone (which was part of the inside of a grave chamber), combined with later evidence from manuscript runes, shows that the original order of the final two staves was D-O and that the Grumpan and Vadstena bracteates were very commonly fashioned with runes as part of their designs. The Kylver stone has, however, reversed the thirteenth and fourteenth staves to read P-EI instead of the usual EI-P order. The Beuchte brooch contains only the first five runes scratched into its reverse side in the futhark order, followed by two ideographic runes—:![]() : elhaz and :

: elhaz and :![]() : jera—for protection and good fortune. On the column of Breza (part of a ruined Byzantine church and probably carved by a Goth) we find a futhark fragment broken off after the L-stave and with the B-stave left out. The Charnay brooch also presents a fragment, but it seems intentional for magical purposes. The brooch of Aquincum bears the first aett, or section of runes, for the futhark complete. (For discussions of the various aspects of the aett system, see chapters 7 and 9.)

: jera—for protection and good fortune. On the column of Breza (part of a ruined Byzantine church and probably carved by a Goth) we find a futhark fragment broken off after the L-stave and with the B-stave left out. The Charnay brooch also presents a fragment, but it seems intentional for magical purposes. The brooch of Aquincum bears the first aett, or section of runes, for the futhark complete. (For discussions of the various aspects of the aett system, see chapters 7 and 9.)

Survey of the Elder Continental and Scandinavian Inscriptions

The most convenient way to approach exoteric runic history is based on the study of the various types of materials or objects on which staves are carved seen through a chronological perspective. Generally, there are two types of objects: (1) loose, portable ones (jewelry, weapons, etc.), which may have been carved in one place and found hundreds or thousands of miles away; and (2) fixed, immobile objects (stones), which cannot be moved at all, or at least not very far.

Figure 1.2. The Elder Futhark inscriptions: a) The Kylver stone, ca. 400; b) The Vadstena/Motala bracteates, ca. 450—550; c) The Grumpan bracteate, ca. 450—550; d) The Beuchte fibula, ca. 450—550; e) The marble column of Breza, ca. 550; f) The Charnay fibula, ca. 550—600; 8) The Aquincum fibula, ca. 550.

Mobile Objects

Runes are found carved on a wide variety of objects: weapons (swords, spearheads and shafts, shield bosses), brooches (also called fibulae), amulets (made of wood, stone, and bone), tools, combs, rings, drinking horn statuettes, boxes, bracteates, buckles, and various metal fittings originally on leather or wood. Most of these had magical functions.

The runic spearheads belong to one of the oldest magico-religious traditions among the Indo-Europeans, and they are among the oldest known inscriptions. The blade of —vre-Stabu (Norway) was, until the recent Meldorf find, the oldest dated runic artifact (ca. 150 C.E.). On Gotland, the spearhead of Moos dates from 200 to 250. Farther south and to the east, we find the blades of Kovel, Rozvadov, and Dahmsdorf (all from ca. 250). There is also the blade of Wurmlingen, which is much later (ca. 600).

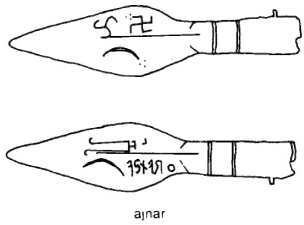

Figure 1.3. Spearhead of Dahmsdorf.

All but Kovel (plowed up by a farmer) and Wurmlingen were found in cremation graves. The Wurmlingen blade is from an inhumation grave. However, their primary function was not funerary; they probably were clanic treasures of magical import that were burned and/or buried with the chieftain. The magical use of the spear in the warrior cult is well known in the Germanic tradition. Hurling a spear into or over the enemy before a battle was a way of “giving” them to Odin, that is, of sacrificing them to the god. Odin himself is said to do this in the primal battle described in the “Völuspá” (st. 24):

Odin had shot his spear over the host

This practice is also known from saga sources.

As an example of these powerful talismanic objects we will examine the blade of Dahmsdorf (found while digging the foundation of a train station in 1865). It is now lost. The blade is made of iron with silver inlay and is probably of Burgundian origin. It is especially interesting because it bears many other symbols besides the runes, as figure 1.3 shows. On the runic side we see a lunar crescent, a tamga (a magical sign probably of Sarmatian origin); the nonrunic side shows a triskelion (trifos), a sun-wheel (swastika), and another crescent. The runic inscription reads from right to left: Ranja. This is the magical name (in the form of a noun agent) of the spear itself. It is derived from the verb rinnan (to run); hence, “the runner.” Its function was, in a magical sense, “to run the enemy through” and destroy them.

The brooches, which were used to hold together the cloaks or outer garments of both men and women, were in use from very ancient times (see Germania, chapter 17). As such, they were very personal items and ideal for transformation into talismans through the runemaster's craft. And indeed it seems that the majority of the twelve major inscriptions in this class (dating from the end of the second century to the sixth) have an expressly magical function. In six cases this includes a “runemaster formula” in which a special magical name for the runemaster is used. The magical function is either as a bringer of good fortune (active) or as a passive amulet for protection.

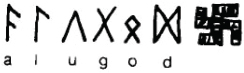

For an example of this type of inscription we might look at the brooch of Værl![]() se, which was found in a woman's inhumation grave in 1944. This gilded silver rosette fibula dates from about 200 C.E. The symbology of the object also includes a sun-wheel, which was part of the original design, whereas the runes were probably carved later; at least we can tell that they were carved with a different technique. The inscription can be read in figure 1.4.

se, which was found in a woman's inhumation grave in 1944. This gilded silver rosette fibula dates from about 200 C.E. The symbology of the object also includes a sun-wheel, which was part of the original design, whereas the runes were probably carved later; at least we can tell that they were carved with a different technique. The inscription can be read in figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4. Værl![]() se inscription.

se inscription.

Figure 1.5. Numerical analysis of the Værl![]() se formula.

se formula.

The Værl![]() se runes are difficult to interpret linguistically. Perhaps it is an otherwise unknown magical formula made up of the well-known alu (magical power, inspiration; which can be understood in a protective sense), plus god (good). The meaning could therefore be “well-being through magical power.” It also could be a two-word formula; for example, “alu [is wished by] God (agaz),” with the last word being a personal name making use of an ideograph to complete the name. However, the magical formulaic dynamism contained in its numerical value is clear, as we see in figure 1.5.

se runes are difficult to interpret linguistically. Perhaps it is an otherwise unknown magical formula made up of the well-known alu (magical power, inspiration; which can be understood in a protective sense), plus god (good). The meaning could therefore be “well-being through magical power.” It also could be a two-word formula; for example, “alu [is wished by] God (agaz),” with the last word being a personal name making use of an ideograph to complete the name. However, the magical formulaic dynamism contained in its numerical value is clear, as we see in figure 1.5.

The numerology of the Værl![]() se formula is a prime example of how numbers of power might have been worked into runic inscriptions. Here we see a ninefold increase of the multiversal power of the number nine working in the realm of six. See chapter 11 for more details on runic numerology.

se formula is a prime example of how numbers of power might have been worked into runic inscriptions. Here we see a ninefold increase of the multiversal power of the number nine working in the realm of six. See chapter 11 for more details on runic numerology.

The bracteates were certainly talismanic in function. Well over 800 of them are known, of which approximately 250 have runic inscriptions. These were not carved but rather stamped into the thin gold disks with the rest of the design, most commonly an adaptation of a Roman coin. The iconography of these Roman coins, which often show the emperor on a horse, was completely reinterpreted in the Germanic territory, where it came to symbolize either Odin or Baldr, his son. It is quite possible that the bracteates represent religious icons of the Odinic cult. They were produced and distributed in and around known Odinic cult sites in what is today Denmark.

Figure 1.6. Runic bracteate of Sievern.

Figure 1.7. Sievern bracteate inscription.

The bracteate depicted in figure 1.6 comes from a German find near Sievern (a total of eleven bracteates). The iconography of the Sievern bracteate is also interesting. According to medieval historian Karl Hauck, the curious formation issuing from the mouth of the head is a representation of the “magical breath” and the power of the word possessed by the god Odin. This can also be seen in representations of the god Mithras. The inscription was badly damaged but probably reads as interpreted in figure l.7. This reading can be understood as r(unoz) writu, I carve the runes, a typical magical formula for a runemaster to compose.

As an example of a wooden object preserved by this process we might take the yew box of Garbølle (on Zealand, Denmark) found empty in 1947. It is designed like a modern pencil box with a sliding top and dates from arouna 400 C.E. The inscription can be read in figure 1.8. The runes are generally interpreted Hagiradaz i tawide: “Hagirad [“one skillful in council”] worked [the staves] in [the box].” The five vertical points after the staves indicate that the reader should count five staves back from there to discover the power behind the runes (:![]() :).

:).

There is also a whole range of fairly unique objects that are difficult to classify. Many of them are tools and other everyday objects that have been turned into talismans, whereas some, such as the famous horns of Gallehus and the ring of Pietroassa, are interesting works of art.

Figure 1.8. Garbølle formula.

Figure 1.9. Formula of Pietroassa.

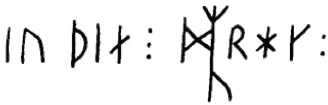

The ring of Pietroassa (ca. 350—400) makes a suitable example for these unique objects. It is (or was) a gold neck ring with a diameter of about 6 inches that would be opened and closed with a clasp-like mechanism. The ring, along with twenty-two other golden objects (some with jewels), was found in 1837 under a great limestone block by two Romanian farmers. Unfortunately, almost all of the artifacts have since disappeared or have been heavily damaged. Of the ring, only the portion with the inscription itself survives, and that in two pieces. These objects seem to have been the sacred ritual instruments belonging to a pagan Gothic priest-chieftain (perhaps even Athanaric himself?). A neck ring was the insignia of sovereign powers in the pre-Christian Germanic world. Figure 1.9 gives the runic forms as we can now read them. They are to be interpreted as Gutani :![]() : wih-hailag. An unclear sign between runes seven and eight is probably a triskelion, and the eighth rune itself is probably to be read as an ideograph ( = othala, hereditary property). Therefore, the translation of the whole formula would be something like “The hereditary property of the Goths, sacrosanct.” For more about this treasure and the Gothic spearheads, see Mysteries of the Goths (Rûna-Raven, 2007).

: wih-hailag. An unclear sign between runes seven and eight is probably a triskelion, and the eighth rune itself is probably to be read as an ideograph ( = othala, hereditary property). Therefore, the translation of the whole formula would be something like “The hereditary property of the Goths, sacrosanct.” For more about this treasure and the Gothic spearheads, see Mysteries of the Goths (Rûna-Raven, 2007).

Fixed Objects

Essentially, there are three types of fixed objects in the elder tradition, all of them in stone but of differing kinds and functions. There are first the rock carvings, cut directly into rock faces, cliffs, and the like. Then there are the so-called bauta stones. These stones are specially chosen and dressed and then moved to some predetermined position. The final group is made up of bauta stones that also have pictographs carved on them.

Four rock carvings date from between 400 and 550, and all are on the Scandinavian peninsula. They all seem to have a magico-cultic meaning and often refer to the runemaster, even giving hints as to the structure of the Erulian cult.

All of the inscriptions serve as a kind of initiatory declaration of power in which the runemaster carves one or more of his magical nicknames or titles. This type of formula can be used to sanctify an area, to protect it, or even to cause certain specific modifications in the immediate environment.

Figure 1.10. Veblungsnes formula.

The simplest example is provided by the rock wall of Veblungsnes in central Norway (see figure 1.10), which dates from about 550. In words, the Veblungsnes formula would read ek irilaz Wiwila: “I [am] the Erulian Wiwila.” (Note that : ![]() : is a bind rune combination of :

: is a bind rune combination of :![]() : and :

: and :![]() :.) The formula consists of the first person pronoun “I,” the initiatory title irilaz (dialect variation of erilaz), the Erulian (widely understood simply as “runemaster”), and the personal name. This name is, however, not the normal given name of the runemaster but a holy or initiatory name. It means “the little sanctified one” or “the little one who sanctifies.” It might be pointed out that the name Wiwilaz is a diminutive form of Wiwaz, which is also found on the stone of Tune, and it is related to the god name Wihaz (ON Vé. “sacred”). In this formula the runemaster, or Erulian, sanctifies an area by his magical presence. He does this by first assuming a divine persona and then acting within that persona by carving the runes.

:.) The formula consists of the first person pronoun “I,” the initiatory title irilaz (dialect variation of erilaz), the Erulian (widely understood simply as “runemaster”), and the personal name. This name is, however, not the normal given name of the runemaster but a holy or initiatory name. It means “the little sanctified one” or “the little one who sanctifies.” It might be pointed out that the name Wiwilaz is a diminutive form of Wiwaz, which is also found on the stone of Tune, and it is related to the god name Wihaz (ON Vé. “sacred”). In this formula the runemaster, or Erulian, sanctifies an area by his magical presence. He does this by first assuming a divine persona and then acting within that persona by carving the runes.

Bauta stones are the forerunners of the great runestones of the Viking Age. Such stones date from between the middle of the fourth century to the end of the seventh, but they continue to develop beyond this time.

Inscriptions of this kind are almost always connected with the cult of the dead and funerary rites and/or customs. As is well known, this is an important part of the general cult of Odin and one with which the runes were always deeply bound. Sometimes the runes were used to protect the dead from would-be grave robbers or sorcerers, sometimes they were employed to keep the dead in their graves (to prevent the dreaded aptrgöngumenn [“walking dead”], and sometimes the runes were used to effect a communication with the dead for magical or religious purposes.

![]()

Figure 1.11. Kalleby formula.

The stone of Kalleby, the formula of which can be seen in figure 1.11, is an example of the runemaster's craft to cause the dead to stay in their graves, or at least to return to the grave after having wandered abroad for a while. These conceptions are common in many ancient cultures. In the Germanic world, the “undead” were often reanimated by the will of a sorcerer and sent to do his bidding.

The Kalleby formula is to be read from right to left thrawijian haitinaz was: “he [the dead man] was ordered to pine [for the grave].” The use of the past tense is very often found in magical inscriptions for a twofold technical reason: (1) the basic magical dictum “do as if your will was already done,” and (2) the fact that the ritual that ensured the will of the runemaster had already been performed before the actual effect was called upon. These conceptions are fundamental to the Germanic worldview concerning the ultimate reality of “the past” and its power to control what lies beyond it. The Erulian uses this to effect his will.

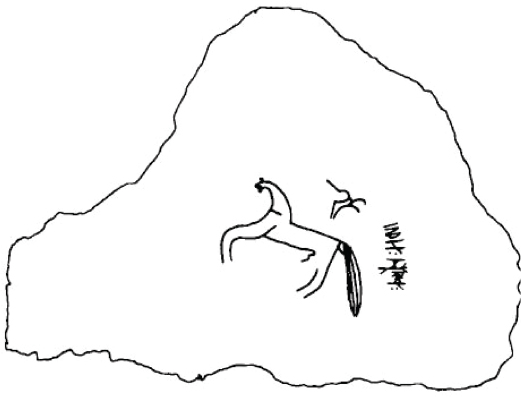

Figure 1.12. Stone of Roes.

The pictographic stones combine runic symbology with pictographic magic. This is especially clear in two of the stones, Eggjum and Roes, both of which have schematic representations of horses (see the E-rune). The tradition of combining runestaves and pictographs appears to be very old, since the oldest of the four inscriptions dates from about 450 and the last (Roes) from about 750. The technique would eventually flower into the great pictographic runestone tradition of Viking Age Scandinavia.

Perhaps the best example of the combination of the runes and the horse image is seen on the Gotlandic stone of Roes (see figure 1.12). This hefty talisman (a sandstone plate 22 by 30 by 3 inches) was found under the roots of a hazel bush during the nineteenth century. The actual runic formula can be read in figure 1.13. Its interpretation is not without controversy, but the best solution seems to be one that makes the complex figure a bind rune of U + D + Z, so that the whole could be read ju thin Uddz rak: “Udd drove, or sent this horse out.” But what is this supposed to mean?

Old Norse literature provides us with a good clue to the significance of this symbol complex. In Egil's Saga (chapter 57) we read how Egil fashioned a nídhstöng, or cursing pole, out of hazelwood and affixed a horse's head atop it. This pole of insult was intended to drive Erik Blood-Ax and his queen, Gunnhild, out of Norway—and it worked.

Before leaving the inscriptions of the Elder Futhark it seems proper to say something about the language they employ. It was at about the time that the runestaves began to be used in writing that the Germanic languages really began to break up into distinct dialects. The language of the period before the breakup is called Proto-Germanic (or Germanic). There also seems to have been an early differentiation in the north that can be called Proto-Nordic or Primitive Norse. The Goths who began migrating to the east (into present-day Poland and Russia) from Scandinavia around the beginning of the Common Era developed the East Germanic dialect (which played an important role in the history of the early runic inscriptions). On the Continent to the south a distinctive South Germanic linguistic group developed what eventually came to include all German, English, and Frisian dialects; whereas in the north Proto-Nordic had evolved into West Norse (in Norway) and East Norse (in Denmark and Sweden). In the first few centuries of the elder period all of these dialects were mutually intelligible; and besides, the runemasters had a tendency to use archaic forms in later inscriptions because they were often ancient and long-standing magical formulas. It has been supposed that there was even a pan-Germanic “sacred” dialect used and maintained by runemasters.

Figure 1.13. Roes formula.

Anglo-Frisian Runes

There are as many reasons for keeping the English and Frisian runic traditions separate as there are for looking at them together. The Frisian tradition is only sparsely known, but it is filled with magical practice; the English is better represented yet less overtly magical in character. However, there are striking similarities in the forms of individual staves, and this fact, coupled with the close cultural ties between the English and Frisians throughout early history, leads us to the conclusion that there was some link in their runic traditions as well. Unfortunately, we have no complete Frisian Futhork.

First let us examine the rich English tradition. The oldest inscription yet found in the British Isles is that on the deer astragalus of Caistor-by-Norwich. It probably dates from the first real wave of Germanic migration during the latter part of the fifth century. But it is perhaps in fact a North Germanic inscription that was either imported or carved by a “Scandinavian” runemaster. This possibility must be considered because the northern form of the H-rune (:![]() : ) is used and not the English :

: ) is used and not the English :![]() :. The dating and distribution patterns of English runic monuments are difficult because the evidence is so sparse and the objects are for the most part mobile. In all, there are only about sixty English runic artifacts, mostly found in the eastern and southeastern parts of the country before 650 C.E., And mainly in the North Country after that time. The epigraphical tradition (i.e., the practice of carving runestaves), which must have begun in earnest as early as 450 C.E.., was extinct by the eleventh century. The runestaves found another outlet in the manuscript tradition. These are valuable for our study but are rarely magical in nature.

:. The dating and distribution patterns of English runic monuments are difficult because the evidence is so sparse and the objects are for the most part mobile. In all, there are only about sixty English runic artifacts, mostly found in the eastern and southeastern parts of the country before 650 C.E., And mainly in the North Country after that time. The epigraphical tradition (i.e., the practice of carving runestaves), which must have begun in earnest as early as 450 C.E.., was extinct by the eleventh century. The runestaves found another outlet in the manuscript tradition. These are valuable for our study but are rarely magical in nature.

The history of the English runic tradition can be divided into the two periods mentioned above: (1) pre-650 (in which a good deal of heathen ways survive), and (2) 650 to 1100 (which tends to be more Christianized, with less magical or esoteric practice in evidence).

The English Futhorc

The only futhorc inscription that remains is on the somewhat faulty Thames scramsax, which dates from around 700 C.E. It is actually a sample of fine Anglo-Saxon metalwork in which the craftsman inlaid silver, copper, and bronze into matrices that had been cut into the iron blade. The order and shape of the runestaves can be seen in Runic Table 2 (Appendix I). This futhorc is followed by a “decorative” pattern and then comes the personal name Beagnoth—probably that of the swordsmith, not the runemaster. As can be seen, there are a number of what seem to be formal errors as well as ones of ordering. All of this is due, no doubt, to Beagnoth's miscopying of a model. It is fortunate that we have more, if later, evidence that shows that in fact the English runic tradition was both well developed and very close to the Continental one. This evidence comes from the manuscript tradition. The most informative document is, of course, the “Old English Rune Poem” (see chapter 8).

The “Old English Rune Poem” contains a futhorc of twenty-eight staves; the codex Salisbury 140 and the St. John's College MS 17 also record Old English futhorcs of twenty-eight and thirty-three staves, respectively. Another manuscript, the Cottonian Domitian A 9 even records a futhorc divided into aettir, or families. Here, it is significant that the aett divisions are made in the same places as those of the Elder Futhark. This demonstrates the enduring nature of the underlying traditions of the Germanic row.

It seems that the oldest runic tradition in England was the Common Germanic row of twenty-four runes, which was quickly expanded to twenty-six staves, with a modification of the fourth and twenty-fourth runes: (4) :![]() : [a] became :

: [a] became :![]() : [o]; (24) :

: [o]; (24) :![]() : had the phonetic value [œ] and later [ē]. In addition, the stave-form :

: had the phonetic value [œ] and later [ē]. In addition, the stave-form :![]() : was relocated to position 25 and named aesc (ash tree). These changes took place as early as the sixth century. As the English language evolved and changed, so did the Old English futhorc. This is the normal way an alphabet develops. As a sound system of a language becomes more complex, so does its writing system.

: was relocated to position 25 and named aesc (ash tree). These changes took place as early as the sixth century. As the English language evolved and changed, so did the Old English futhorc. This is the normal way an alphabet develops. As a sound system of a language becomes more complex, so does its writing system.

The use of English runes can be divided into three main classes:

Loose objects

Fixed objects (e.g., stones)

Manuscripts

The loose objects represent the broadest category. They are generally the earliest type of inscription, yet they also persist to a late date. Unfortunately, many of them are fragmentary or damaged to such an extent that exact readings are almost impossible. Most of the mobile objects have the runes scratched into metal, bone, or wood; however, some represent the staves by more intricate techniques of metalwork (see the Thames scramsax) or fine wood/bone carving (e.g., the famous Franks Casket). The Old English runestones mostly date from the Christian period and seem to represent a pseudo-Christian adaptation of the tradition, but they may still have magical, and certainly religious, import. Most of them are actually memorial stones or stone crosses and were carved by skillful stonemasons.

There is no Old English manuscript entirely written in runestaves, but they are nevertheless widely represented in the literature, where they serve both cryptic and pragmatic ends. Two runes were adapted by the English for writing with pen and parchment in the Roman alphabet; they were the p <:![]() : [th] (thorn [thorn]) and the P <:

: [th] (thorn [thorn]) and the P <:![]() : [w] (wynn [joy]). From there this orthographic practice was taken to Germany and to Scandinavia.

: [w] (wynn [joy]). From there this orthographic practice was taken to Germany and to Scandinavia.

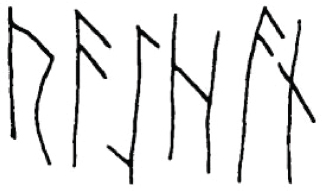

Figure 1.14. Caistor-by-Norwich inscription.

The Caistor-by-Norwich inscription mentioned above is a good example of the loose type of object from an early period. Its runes appear in figure 1.14. This bone was found with twenty-nine other similar ones (without runes), along with thirty-three small cylindrical pieces, in a cremation urn. It is possible that the objects were used as lots in divinatory rites. The inscription itself is difficult to interpret, but it may mean “the colorer” or “the scratcher” and be a holy name of the runemaster.

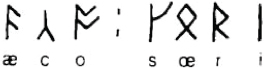

An explicit example of magic used by the Odinic runemasters is hard to come by in the English material, but the scabbard mount of Chessel Down (see figure 1.15) is probably one. The inscription was scratched on the back of the fitting and is thus invisible when in place. It might be translated as “Terrible one, wound [the enemy]!” If this is so, then æco (terrible one) would be the name of the sword, and særi (wound [!]) its charge.

Figure 1.15. Chessel Down formula.

An interesting example of a magical runestone from the pagan period is provided by the seventh-century Sandwich stone. It probably represents the name of the runemaster, Ræhæbul, and was originally part of the interior of a grave. The text, as best it can be made out, can be read in figure 1.16.

Figure 1.16. Sandwich inscription.

Among the manuscript uses of the runes, the one most approaching magical practice is the concealment of secret meanings in texts through the use of runes. One such text is found in Riddle 19 of the Exeter Book,1 which translated from OE would rsead:

I saw a ![]() (horse) with a bold mind and a bright head, gallop quickly over the fertile meadow. It had a

(horse) with a bold mind and a bright head, gallop quickly over the fertile meadow. It had a ![]() (man), powerful in battle, on its back, he did not ride in studded armor. He was fast in his course over the

(man), powerful in battle, on its back, he did not ride in studded armor. He was fast in his course over the ![]() (ways) and carried a strong

(ways) and carried a strong ![]() (hawk). The journey was brighter for the progress of such as these. Say what I am called . . .

(hawk). The journey was brighter for the progress of such as these. Say what I am called . . .

Here, the runes spell out words, but they are written backwards in the text. So the runic words read hors (horse), mon (man), wega (ways), and haofoc (hawk). However, and this is a remarkable and mysterious thing, the individual rune names were to be read in the order as written so that the poem would have its proper alliteration.

Frisian Runestaves

No Frisian Futhork exists, but we do have a small body of interesting inscriptions. There have been about sixteen genuine Frisian monuments found so far (there are also a number of fakes). They date from between the sixth and ninth centuries. These inscriptions are generally found on wooden or bone objects that have been preserved in the moist soil of the Frisian terpens (artificial mounds of earth engineered in the marshes as an early form of land reclamation).

Frisian runic monuments seem to have a distinctly magical character, but many of them are difficult to interpret. We can be sure that they occur in a solid pagan context because this conservative region, often under the leadership of heroic kings such as Radbod, resisted the religious encroachment of the Christians—along with the political subversion of the Carolingian empire—until the late seventh century. We can even safely assume a period of reluctant religious compliance until long after that.

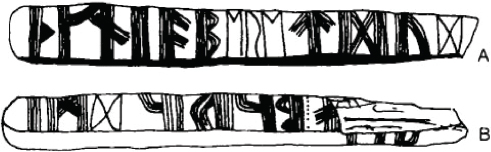

One of the most interesting, if difficult and complex examples of these Frisian pieces is the “magic wand” or talisman of Britsum (figure 1.17), which was found in 1906 and which dates from between 550 and 650. The wand is made of yew and is about 5 inches long. Side A of the inscription reads from left to right: thin ī a ber! et dudh; side B can be read from right to left: biridh mī. The damaged part of the piece cannot be read. The whole formula is translated “Always carry this yew [stave]! There is power [ dudh] in it. I am carried. . . .” It might be pointed out that the seven-point dividing sign on side B indicates the seventh rune following the marker; that is, :![]() : (in this inscription) = :

: (in this inscription) = :![]() : yew—the power contained in the formula.

: yew—the power contained in the formula.

Figure 1.17. Wand of Britsum.