Pagan Portals - Guided Visualisations: Pathways into Wisdom and Witchcraft - Lucya Starza 2020

Gwyn and the Mabinogion

The earliest written collection of prose tales in Britain, the Mabinogion, or Tales for Boys, is dated to the twelfth to thirteenth centuries. Compiled from earlier manuscripts and traditional oral lore, the Mabinogion — or more accurately, the Mabinogi are a collection of eleven tales recorded mainly in the White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1350) and The Red Book of Hergest (c. 1400) where we encounter the realm of Annwfn in wonderful detail.

In what is usually called ’the first branch’ we encounter ’The tale of Pwyll Prince of Dyfed’ and meet the King of Annwfn, named here as Arawn, which is likely to be another name for Gwyn, perhaps drawing on his other earthier attributes — the name Arawn may come from the Celtic for ’Tiller’ or ’God of the ploughed field’. Gwyn is explicitly mentioned more fully in The Tale of Culhwch and Olwen which is also part of the collection, and which we will cover in some detail.

The tale of Pwyll Prince of Dyfed

Pwyll is hunting when he comes across the Cŵn Annwfn, the faery hounds, and takes their kill — a white stag — for himself. The leader of the Cŵn Annwfn, Arawn then appears and is mightily offended. As an act of recompense Pwyll agrees to swap places with Arawn for one year and defeat his enemy Hagfan for him. During this time, he is also to share a bed with Arawn’s wife, without touching her once. Arawn’s wife is not named in the tale, but functions as both a goddess and a symbol of sovereignty and the soul of the land over which Arawn, as a double for Gwyn ap Nudd, is guardian. As a result of this Pwyll learns responsibility and self-restraint, and perhaps even to control a Celtic form of kundalini, which is hinted at in numerous other tales, such as in the Irish examples of training the Fianna and Cúchulainn’s battle frenzy. Pwyll learns to control his baser urges be they sexual or otherwise and becomes a worthy and honourable king due to the experience. He is granted a great alliance with Arawn and on his return, notes that Arawn has ruled his earthly kingdom well in his absence. The tale as a whole can be seen as a manual for spiritual training — by communing with but still holding as sacred, the goddess of the land herself, one learns wisdom and a deeper soulful communion with the earth in its spirit form. One discovers the vivifying currents which can sustain rightful sovereignty within oneself and on behalf of others.

The Tale of Culhwch and Olwen

Later in the Mabinogion is the Tale of Culhwch and Olwen. Culhwch (culoowk) is the cousin of King Arthur, and enlists his help in order to win the hand of the maiden Olwen. Olwen ’white footprint’ is the daughter of Yspadadden Penncawr, ’King of giants’ and is said to be so beautiful that white flowers spring up under her feet. Yspadadden sets Culhwch over forty impossible tasks to prove his worthiness to marry Olwen, and Arthur grants Culhwch several of his men in order to complete the challenges. One of these tasks is to hunt a huge magical boar named Trwch Trwyth who is himself the son of a prince under enchantment and who can only be slain with the help of Gwyn ap Nudd. Twrch Trwyth, or ’the boar named Trwyth’, has poisonous bristles and carries a pair of scissors, a razor and a comb between his ears. Trwyth may be cognate with the Irish Triath, making his name ’king of boars’ (Old Irish Triath ri torcraide) which could place him as the same magical Boar, the Torc Triath mentioned in Lebor Gabála Érenn, the book of the Taking of Ireland, the great body of Irish creation myth.

Boars in Celtic myth as in nature are fierce creatures, and their appearance in tales usually signifies leadership and responsibility, even royalty, but there is always something Otherworldly or underworldly going on as well. Boar imagery in Iron Age Celtic art is connected to ideas of war and images of boars or boar tusks were popular on warrior’s helmets. Boars in nature are usually very shy creatures, and the tutelary goddess of the Ardennes forest in France, Arduinna who is depicted riding a boar most likely represents the power and sovereignty of her land for its wild as well as its human inhabitants in peaceful balance, without any negative connotations. Later a recurring motif was for boars to represent the chthonic underworld forces of chaos and darkness which were sacrificed or defeated by the new or light gods or heroes. Yspadadden in the tale has one of his servants lift up his eye with a fork, and this may be reminiscent of the solar imagery which can be seen in the Irish tale of Balor of the baleful eye, which requires a chain to open it. Balor, like Yspadadden wants to deny his daughter a husband as it would bring on his demise, and is defeated in the end by the new god Lugh, his grandson, in a new sun god beats old sun god motif which is seen repeatedly across Northern Europe. It may be that Culhwch defeating the boar, and thus in effect defeating Yspadadden’s challenge, repeats this pattern in the Welsh tale. Culhwch also, like Lugh, pierces the giant’s eye with a spear, although in the Welsh tale, unlike the Irish this isn’t fatal. The character of Yspadadden as well as the great boar can also be read as the quest to defeat the old pagan gods and war leaders in favour of a more-courtly Christianised ideal represented by Arthur and his retinue, the pivotal character of Culhwch facilitating the change but having equal investment in both worlds.

Boars, like pigs in Celtic myth also have healing and visionary qualities and are often associated with the figure of the divine madman or prophet, who seeks a living as a swineherd in the forest outside of the human world. The name Culhwch is also connected to pigs and boars, as it is thought to mean ’pig run’, or even pigsty — the name given to him as it was the place of his birth, suggesting he lives upon the cusp of this world and the next.

Gwyn ap Nudd enters this tale as an essential companion when hunting for the boar alongside his eternal rival Gwythyr ap Greidawl. The boar, as already mentioned, is actually a prince under enchantment, a son of Prince Tarred Wledig, but there is no freeing him from the curse. He rages across the land and the task of his hunters is to seize the razor, scissors and comb from his head to appease Yspadadden before chasing him into the sea. Later in the tale another, the chief of boars, Ysgithyrwyn is also hunted for his tusk, his primal power. To see Gwyn in this hunt, mentioned as essential to the task hints at his role as psychopomp, representing and overseeing the death process, freeing the prince from his enchantment by returning him to the sea, and Annwfn, where he can restore and prepare for his next life.

Sovereignty and the eternal battle

In the Mabinogion, the tale of Culhwch and Olwen takes many meandering turns in order to tell the tales of various other characters as the story progresses, and one such is the eternal love triangle of Gwyn, Gwythyr and the maiden Creiddylad.

Creiddylad we are told in the tale is the daughter of Lludd LLaw Erient — Lludd being another version of Nudd/Nuada/Nodens, yet here the etymology gets tangled, and Lludd is also often taken to be another name for LLyr — the sea god, cognate with the Irish Lir. Gwythyr ap Greidawl (Victor son of scorcher) is due to marry Creiddylad, who is described as ’the most majestic maiden there ever was’9 yet Gwyn abducts her before the marriage is consummated. Gwythyr raises an army against Gwyn, but is defeated, and several of his noblemen are captured. Two of his prisoners are Nwython and his son Cyledr and in a curious development Gwyn in his fury kills Nwython and forces his son Cyledr to eat his heart. Cyledr is driven mad by this and gains the epithet Wyllt (wild) upon his name — suggesting he undertakes a magical/spiritual transformation into a visionary and prophet.

Gwythyr ap Greidawl, victor, son of scorcher, may be understood as having solar and sky attributes as well as representing summer, scorcher being likely to refer to the sun. As such we can imagine him as active in the mortal or upper world realms, a character concerned with fertility, heroism, youth and the gaining of prestige in the mortal world — through being active in life. In contrast, Gwyn as lord of Annwfn places him firmly in the inner or underworld, where self-awareness, transformation and transmutation takes place, where the soul is tempered and matured. All this inner growth takes place beneath the surface of things, and this together with his connection to Nos Calan Gaeaf/Samhain (Oct 31st) and the wild hunt and his role as psychopomp place him firmly in the seasonal wheel in the place of winter. King Arthur places himself as the ultimate arbiter of their duel and condemns them to fight every 1st of May (Calan Mai/Beltane) for Creiddylad’s hand until the end of time, in a pattern echoing the seasonal wheel of the land ever turning from summer to winter and back again.

Creiddylad, despite being called ’majestic’ is less easy to interpret. Creiddylad’s name seems to defy translation, but we see from her lineage that she is born from either the god of the sea, or the inner depths of dream/mist/cloud/firmament of Nudd/Nuada. Both these gods are concerned with an in-between state, some place outside of the quantifiable matter and physicality of the mortal world. Yet she herself is described as ’majestic’ — having majesty. This links her irrefutably with that perennial concept in Celtic lore — that of sovereignty, the royal soul of the land which appears in many tales and is usually embodied by a female figure. During the eternal battle for her hand, King Arthur states that she returns to her father’s kingdom until such time as the matter is settled.

The fact that Gwyn’s father is also Nudd/Lludd/Nuada/Nodens is not mentioned in the tale. He is not named as her brother and it may be that the connection between Lludd and Nudd was overlooked or considered to be of no consequence — certainly this isn’t a matter of incest or brotherly jealousy, rather an enticing clue into a long-lost initiation and mystery teaching.

That Gwythyr and Gwyn battle over her, in what can be understood as an eternal struggle between winter and summer and that she seems to arise from an Otherworldly and intangible spirit state to touch the mortal world only briefly seems to add weight to her as an embodiment of sovereignty and soul, one that infuses the land with life but is none the less held beyond it in a seemingly timeless space within the land. That Gwyn is never defeated by Gwythyr places him in a similar position, dwelling in the centre and heart of the land and arising out of it to encounter the challenge from Gwythyr, an external (solar) force from a place of still centrality rather than a linear or ever-turning exchange of places.

In the tales of Gwyn ap Nudd, Creiddylad is an elusive figure. In the Mabinogion all we have to describe her is that she is ’majestic’ and that she is ’betrothed’ to Gwythyr and kidnapped by Gwyn before returning to her father, Lludd. In the dialogue of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir we have the additional detail that Gwyn is her ’lover’ — note he says he is the lover of Creiddylad, not that she is his — implying his love and respect rather than any sense of ownership. At no point does he call himself the captor of Creiddylad. We also know in oral tradition from the fourteenth century that she was called his queen and was invoked in seeking permission to enter his kingdom — the wild wood.

…to the king of Spirits, and to his queen — Gwyn ap Nudd, you who are yonder in the forest, for love of your mate, permit us to enter your dwelling.10

Again, here Gwyn’s love for her, and her implied generous nature give us hints as to her personality or identity, and her relationship with him.

If looking at the Gwyn-Gwythyr-Creiddylad triangle from a feminist perspective she may seem powerless and unrepresented — certainly, we never hear her voice or will. That said we must remember that this tale was written down in the mid-thirteenth century, and although it is likely based on far older oral sources, the language and structure of the tale is based in that context. As such the courtly maiden is silent while male protagonists battle for her hand and we can only infer her preferences in the matter. Certainly, if we consider it on the level of human relations we know that while she may be betrothed to Gwythyr this indicates nothing of her feelings or lack of them for him, and the same can be said for Gwyn. It may be that as he is elsewhere termed her lover there may have been earlier lost versions of the tale where their relationship was more explicit, either sharing mutual affection or as kidnapper and victim. Equally Gwythyr may have been her favourite, or neither. It may even be somewhere in between — as a pagan mystery tale it may reflect the emotional and sexual complexities of a wild and soulful female protagonist — or the eternally shifting affections of nature herself — she may love them both each in their season. What we do know is that the fragments remaining and later folk tradition make Gwythyr very much the third wheel in this triangular relationship, and that for the most part we can view Creiddylad, in the context of the tales at least, as being either Gwyn’s queen — he after all wins the battle against Gwythyr despite its annual rematch, or that she dwells mainly in the third place — the realm of her father Lludd.

There is, however, another less analytical way to explore the nature of Creiddylad if we view her with the eyes of the soul and inner knowing. If we consider her father to be the Lludd/Nudd/Nuada/Nodens who has his roots in the tradition of divinatory dreaming, and the in-between ethereal realm of clouds and mist and lunar corresponding silver hands, we see she must have her origins in some place infused with spirit. Just as Gwyn’s name means white or blessed/holy, it may be that Creiddylad’s name whose meaning is now forgotten may once have had related connotations — certainly they seem to share the same source.

The idea that Gwyn and Creiddylad may be brother and sister never arises in the tales or oral lore and this is significant, as other familial relationships are clearly related and even rape and incest is touched upon in other tales in the Mabinogion, so we know those writing down the stories weren’t averse to including these details. There are also precedents in other cultures where brother and sister gods appear to be couples — the Egyptian Isis and Osiris is perhaps the most famous but others can be found around the world. In the Brythonic lore, we have it that Gwyn is the son of Nudd and Creiddylad is the daughter of Lludd and while these are both forms of the same originating deity this fact appears to be overlooked by those writing the tales. It may also be that their familial relationship isn’t the point — that to share this father is not the same as it would be in a mortal human relationship — rather, that, as the name Nudd and Lludd suggests, they both emerged from the mists, through the veil between the Otherworld and this.

If we see Creiddylad in this context, as an Otherworldly woman who none the less represents or even embodies the figure of sovereignty then we must understand her not as a medieval female character or a figure of Celtic myth in merely narrative terms. We can view her as a being who moves to and fro between the worlds, drawing Otherworldly energy with her and imbuing this quality into the land she represents — that she embodies not the physical matter of the land but its spirit representative, its soul. Thus, her return through the misty veil returns her to the spirit world, the realm of Annwfn guarded by her ’lover’ Gwyn, but her role to bless and bring fertility to the land continues year on year as she emerges at Calan Mai/Beltane, and Gwyn and Gwythyr battle for her hand, to recede back to ’the deep place’ of Annwfn within the heart of the land every time Gwyn eventually wins, presumably at Nos Calan Gaeaf/Samhain when we see him ascendant once again.

The two-faced god

There is another way to understand the relationships between Gwyn, Gwythyr and Creiddylad, when we take into consideration the prolific two- or sometimes three-faced ’Janus figures’ found across the Iron Age Celtic world. Stone sculptures such as those found on Boa Island, Ireland are fascinating sculptures, featuring two distinct figures facing in opposite directions with their bodies merging into one. Others such as the one found in Roquepertuse, France (600-124 BCE) are just the heads, with a stone vessel between them perhaps for receiving offerings and libations. While these sculptures are usually called ’Janus’ figures, after the Roman god of Doorways, beginnings and endings — hence looking in both directions, they are often now thought to be representations of a pre-Roman Celtic god or gods — the two faces representing the duality of their nature. It may be that Gwyn and Gwythyr in their eternal struggle are a natural pair or two sides of the older deity, Vindonnus-Belenus, concerned with life and death, winter and summer, youth and age etc., one side in Annwfn or the underworld, the other in the upper world/solar/sky, each aspect serving the goddess in turn.

Practice: Meeting Gwythyr

In this meditation journey, we will use our inner vision to seek the council of Gwythyr ap Greidawl ’Victor son of Scorcher’ to seek wisdom and encounter the virile solar currents that fertilize the earth.

This exercise is best performed with the sun on your face, or with the heat of a fire or the flicker of candlelight before you which you may sense through your closed eyelids.

First sitting upright, close your eyes and take three deep breaths. Call to your guides and spiritual allies, whether you know them by name or not, trust that they attend you, then state your intention out loud to seek an encounter with Gwythyr.

See yourself standing in a great stone archway, with a clear, dry, dusty path ahead of you leading up a broad hillside in the heat of summer. The grass is dry although still green, insects buzz low through the upright stems of cowslip and hemlock flowers and settle lazily on the deep green leaves of elder and hazel that spring up here and there along your route. Gradually as you walk you see you are leaving a lowland meadow and climb higher into the craggy hillside, and the trees become larger as if you enter into gradually wilder terrain. You notice there are many large oak trees here and there around you and the leathery green of holm oak and holly leaves lends brief moments of shade along the path. You go further and the trees open up to high moorland and vast swathes of broom and golden gorse blossom surround you together with rough purple heather. The sky above is bright blue and cloudless and the deep heat of summer beats down upon you.

Ahead you see that the line of the hillside above you flickers with golden light, and a heat haze shimmers in the air above the horizon line. As you grow nearer you hear the crackle and snapping sounds of fire on the hillside. The gorse and heather are aflame.

You carry on the path, aware that there is danger here, that while there is no wind the path of the fire is predictable, but it could change at any moment. You are not afraid, but there is a sense of drama and excitement in the air, a fierceness in the flame that draws you forward and yet sets your heart racing. You pause and call your guides and allies to you once more, and only continue should you feel it is appropriate to proceed.

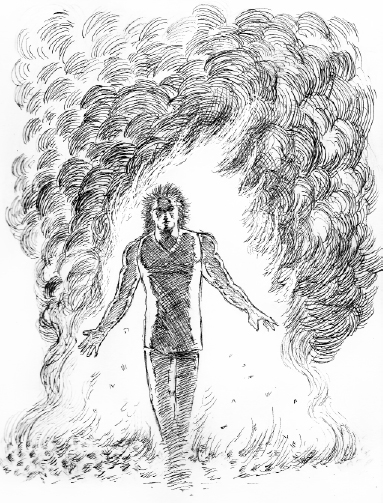

As you rise to the next level of the hills you see the fire has spread across a whole field of gorse and heather and the golden flames and golden blooms seem to turn and transform one into the other and back again in fluid fiery motion. Though there are areas of rich black burnt earth here and there where the fire has receded, it seems that from where you stand the whole hill is afire. The air tingles and shimmers with heat and your eyes find it hard to focus for a moment, and then across the hill you see the figure of a man striding through the flame. His hair is golden red and his strong arms swinging free of a golden-brown tunic are strongly muscled and visibly shimmer with sweat. As he walks towards you through the flames you realise this miraculous figure is far taller than any man and though he walks through the fiercest flames he is unburnt. As he gets nearer you see that as he raises his hands through the gorse the plants shoot upward into new green life, burst into golden blossom and then crackle and explode into flames all at his touch. Far behind him, the dark earth of the burnt hillside grows steadily, and then turns green with new life like a great verdant wave.

The man pauses a few feet from you, and the fire seems to calm. Instead new growth shoots from the gorse and blossoms golden all around him. You look up into his face and you see his cheeks are flushed and his amber eyes glow with life.

This is Gwythyr, lord of summer fire. He knows the secrets of heat and light and regeneration but also the powers of fire and fury.

Spend some time here in his company, feel the heat that radiates from him. He may have advice for you about how to seize your own victories, or how to handle your own passion and energy better. It may be that there are parts of you or your life that you would offer to his flames for transformation, and you can seek his wisdom and assistance on this also. Remember though to always be respectful in case his warmth should turn into destroying fire.

When you are ready thank Gwythyr for his wisdom, and bow your head briefly in respect. Return the way you came down through the hills and back through the stone archway, returning to your body gently and easily.

Feel the breath in your chest, and breathe in and out a few times, and wiggle your fingers and toes to feel yourself back firmly in your body. You may like to record your experiences in a journal.

Afterwards, you may like to have a special pillar candle that you can light repeatedly in honour of Gwythyr whenever you seek his wisdom or support, and when you are low in physical energy and health to attract more of his robust energy and light into your life. You may also call upon him when you seek victory in a dispute, as long as that which you seek is just, not against your own inner nature, or the deep wisdom of nature herself.

Encountering sovereignty

The figure of sovereignty appears throughout Celtic and Arthurian lore. Representing the soul and heart of the land, as well as being its incarnate goddess she is a figure often mistreated and misunderstood, battled over by dual forces of summer and winter, good and evil, youth and age, or denigrated, denied and abused by a single male protagonist until he finally acknowledges her worth or succumbs to her vengeance. Her appearance varies, and how she is ’seen’ by the protagonists of the tales tells us a lot about their attitude to her and their relationship to the land, as well as their own inner lives. She’s often a woman, often beautiful, but this is only her friendly face, in many ways her most passive stance as the figure over which others fight. Sometimes she’s ancient and ugly, often when others need lessons in humility or need to restore honour. But sometimes she’s an animal, such as a horse or a swan, and there is something especially ancient here as if the call to discover her means more than encountering the spirit or soul version of the mortal world — to encounter her we must encounter the wilder self, the animal self and we are reminded she oversees the whole of the land not only human affairs. She appears in both the Brythonic, Irish and Scots literature and oral tales, and can be traced right through into Proto-Indo-European culture, found as far afield as India and Sumeria in the tales of Vishnu and Lakshmi, Dumuzi and Inanna. In Arthurian sagas she has many guises, most commonly in Guinevere as well as being embodied and symbolised by the grail — here the cup of Christ is transposed upon that more ancient symbol of womb-like sacred vessel the cauldron.

In Celtic culture, the figure of sovereignty was represented by numerous earth and mother goddesses who bestowed health and fertility on the land, and evidence suggests that rites of sacred kingship involved ritually or physically mating with her in order to achieve legitimacy. It is argued by some scholars that in Ireland such kings may even have had a set term or lifespan before being sacrificed to her — the evidence of bog bodies — possibly the victims of ritual killings preserved in the peat bogs below hills used for ritual, could point to this among other interpretations.11 However, that such a tradition persisted in Ireland at least until relatively recent times is attested to in the work of Giraldus Cambrensis. In his Topographia Hibernica (1188) Cambrensis makes no attempt to hide his disgust at the installation of the Ard Ri — the High King at Tara which involved the king’s sexual contact with a white mare who embodied the sovereignty of the land as part of the rituals known as the feis temrach and fled bainisi.

In the tale of Culhwch and Olwen we see sovereignty appear in several guises as this tale of tales weaves in a myriad of other related lore. In many ways Olwen is a version of sovereignty — her love is a hard-won prize — but we really see sovereignty revealed in the figure of Creiddylad, fought over every Calan Mai/Beltane (May 1st) by Gwyn and Gwythyr, the night and day, winter and summer, under and upper world guardians and representatives, in their endless battle for her hand.

In some ways sovereignty is something that is always fought for; it cannot come easily from birthright or any political system. It is a place of harmony and balance where all is literally ’all right with the world’, a state of blessedness and heavenly wholeness. However, this state must be continually in flux. If it was to stay forever there would be no growth, no maturing, no sense that it was to be valued and honoured. It is a state of spirit; its place is in the realms of the divine not the mortal world yet the quest to bring it to the mortal world is a divinely ordained one whereby wisdom and a soulful life may be achieved. Sovereignty must come, and in its time return from whence it came just as Creiddylad returns to her father — to be reclaimed during the next cycle, or by the next generation. Sovereignty, soul, connection with the goddess or finding the grail must by its very nature be a prize not an entitlement and those who seek it must know its value — in fact knowing its value is the prize itself — its attainment is a recognition or re-remembering of the soul, a return to the senses where the beauty and sanctity of the land becomes visible once again and our relationship to that divine state is restored.

To find sovereignty in our own lives is a continuous journey and one that will need to be repeated over and over for most people as our connection to it waxes and wanes and waxes once again. At first, especially with the enthusiasm and confidence of youth such an attainment may seem easy, it may even appear as if no quest or battle is required. This is most often, however, a state of naivety rather than sovereignty — a presumption that no work needs doing, that there is nothing waiting in the shadows. With time, however, we see how life saps us of sovereignty, drains it away with daily concerns or denies us enough power over our own destinies to encounter such a vivifying presence, and so the quest must begin. If we are not sovereign in our own lives we can be sure that someone or something else is, and that must be tackled if we are to marry the queen of the land or finally recover our own soul’s treasure.

On a wider perspective, regionally and nationally, sovereignty is even more complex — our mortal kings and queens and political structures may claim sovereignty of one sort or another but it’s unlikely they could ever be considered to represent the goddess of the earth or her consort, unless it is as a means of creating moving propaganda to stir the hearts of the population; as a tool of control not as a way to vivify and bless the land or to restore health and wholeness for all creation. There is something universally stirring about sovereignty that pulls on every heart but sadly the days of royalty and other leaders serving as go-betweens, enacting the sacred marriage as the bond between the people and the gods, is long gone, if it ever was other than in myth. Instead sovereignty is an elusive figure, something that calls to us with an inner yearning, something that will wake us in the night or stir us to tears at a sunset but is easily over looked in the brash light of day. What we are left with are tales, examples and clues to help us each forge this bond, defeat our counter point and follow this quest ourselves until we finally hold the goddess in our arms, or our own soul is restored once again. We do this by learning to hear our inner voice, the wisdom of our own heart — becoming ’true of heart’ as the old tales say and following the energetic and fateful streams of what is inherently healthy and wholesome back to the Source.

Practice: The dark mirror. Seeking wisdom from the unseen

In this meditation journey, we will seek a vision from the dark mirror, the waters of Annwfn, to better know ourselves, and to let go of what no longer serves our growth and healing, that we may be better prepared to meet our sovereignty and wholeness.

This is best performed somewhere quiet where you are comfortable but will remain uninterrupted for at least half an hour.

First sitting upright, close your eyes and take three deep breaths. Call to your guides and spiritual allies, whether you know them by name or not, trust that they attend you, then state your intention out loud to seek an encounter with the waters of Annwfn.

In your inner vision see that it is dusk, and you stand on a narrow path between low trees. You follow the path as the light fades, until it opens onto an expanse of reeds and willow trees, rising taller than your head, so that your view is limited. The air smells damp and is full of the sounds of marshes, of croakings and chirrups and the lonely call of geese gathering out of sight. The path leads you onwards, until it forms a narrow trackway of split timbers supported by timber posts pushed crosswise into the marshy waters. On either side you can see through the reeds and weeds, dark water beneath and around you. You must step slowly and carefully, one foot after another.

Let your inner vision focus on your feet, while all around is darkening, one step after another, slow as a drum beat. Your breathing also slows to match the rhythm so you seem to glide slowly, carried on your breath along the narrow way, as if along a thread.

Suddenly ahead you see the path widens into a platform upon the waters, and you see you are breaking clear of the reeds and the path has lead you through to open water. Night has gathered in now and above you the sky is brilliant with stars. Everything is so still and quiet, you can see them reflected clearly upon the water. The effect is strange, and disorientating but very beautiful, as if you stand upon the edge of space. Above you the constellation of Orion stands tall, with the dog star Sirius at his heel. Below they are perfectly reflected. Take a moment to consider this vision, breathing slow and let its inner magic work upon you.

“What do you sacrifice in this ancient place?” The voice shocks you from your meditation, and you see a figure in the darkness, standing a few feet away. You guess that it is a man by the tone of their voice, but they are completely shrouded, wrapped in black, their face is hidden or darkened by paint and ashes so that only the glimmer of their eyes can be seen. How do you answer? What are you willing to let go of at this time? Something appears in your hand, it may be an object or something else, perhaps something symbolising a thought, a feeling or a memory. The figure takes it from you and looks at it carefully, he may have words of insight or guidance for you, before handing it back.

“Give it with your care to the waters,” he commands. You kneel at the edge of the platform and place your object carefully into the lake. To your surprise, you see too that your reflection can be clearly seen, as if you reach up from the darkness to take the gift from yourself. Your hands shift and distort as they are seen through the water, and you let your sacrifice go, sinking into the blackness in front of you. “Now, look well and look deep,” commands the figure, and you take a moment to study your own face reflected as if in a dark mirror. Other images may also pass before you. What do you see? Are you the same as in the daylight world? Here you may find another truth.

“This is your gift from the waters,” says the man, who you know now to be the guardian of this ancient place. And you know that the wisdom of your vision is a gift indeed, though it may take some time to know its meaning.

You rise slowly, and bow your head in respect of this strange teacher. Give him your thanks and return the way you came. Follow the track through the marshes and the trees, focusing on your breathing, until you see the trees fade and your sense of your body grows stronger once again.

You see you have returned to your body far quicker and easier than your outward journey. Take your time, wriggle your fingers and toes and let your consciousness return gently and fully.

Practice: Meeting Creiddylad

In this meditation journey, we will seek the council of Creiddylad daughter of Lludd, mysterious goddess of spring and sovereignty.

This exercise is best performed somewhere quiet where you are comfortable but will remain uninterrupted for at least half an hour.

First sitting upright, close your eyes and take three deep breaths. Call to your guides and spiritual allies, whether you know them by name or not — trust that they attend you, then state your intention out loud to seek an encounter with Creiddylad.

In your inner vision see yourself standing at a great stone archway, and ahead of you is a simple path of pale stone and soft earth, winding its way along a tunnel of hawthorn trees. You step out onto the path and the light around you is soft and blue — you cannot tell if it is dusk or early dawn but there is a cool freshness in the air and the scent of green leaves and good earth. Ahead of you swoops the pale shape of an owl hunting, though you do not hear her lonely call. As you follow the path, the way ahead is dappled in light and shade — deep impenetrable shadows and the lighter areas seem to shimmer silver, and you sense that indeed dawn is near. Overhead the branches of the trees begin to sigh in a soft breeze and you are startled to hear a heavy shuffling noise to your right — you turn your head but cannot see its source. You let your eyes grow more accustomed to the light and you begin to see through the hawthorn branches into the space beyond. In between the tree trunks and twigs you realise you can see a large field, a huge grassy mound arcing off ahead of you and alongside the path you are on. In the field, just a few feet away a beautiful white horse is standing, head bowed munching on some fresh grass. It raises its perfect silver head to gaze at you with large steady eyes. You take a moment to gaze at the beautiful white mare.

When you feel it is time you continue on your way along the path, which rises steadily before opening out onto the base of a large steep hill, a conical mound that reaches up to the sky, its sides wreathed here and there with morning mist. The pale path spirals around the side of the hill and carries you steadily to its summit.

When you finally stand on the top of the hill, the vast expanse of the land around you is staggering — all around you see emerging, as if from a white cloud, rolling hills and distant mountains, you see lakes and deep forests, open plains and further off the amber glow of streetlights and houses, lining the far horizon with deep golden light, ever flickering, never still, like distant fire.

Suddenly the wind stirs your hair and you hear distant bells chiming, small and delicate yet clear through the cool blue air. You follow the sound and look down at the foot of the hill beneath you. The white mare still stands tall and proud in the green field, but now the air shimmers about her as if a great unseen faery host swirls all around. In the distance, you see a woman dressed in white striding over the land, she seems impossibly tall, crossing whole fields in one step, yet she is delicate and graceful in all her movements. All around her there is a shimmer and a shift in the air, a great warm sigh in the earth although nothing shakes or is broken. There is a change which you feel in your very blood but is impossible to define, or describe. It is as if the land itself rejoices and blooms and grows rich at her passing, where her feet tread the land becomes somehow more real, more alive in your vision.

Her voice comes clear and cool through the blue air.

“Why do you seek me child of earth?” You were not aware that she had climbed the hill, yet she stands before you now. Her eyes are calm and clear, her soft brown hair glints with gold as the sun begins to rise. Your heart thuds in your chest. Let it speak your truth to her now, in this most sacred place.

She may grant you wisdom, or She may not, but either way take this moment to connect with this most majestic maiden, for She has much to teach if She is willing, and if you are able to hear.

After a while it may be clear or you may feel that your audience with Creiddylad is coming to its close. Thank Her for her wisdom, and bow your head briefly in respect. Return the way you came down the hill and back through the hawthorn tunnel to the stone archway, returning to your body gently and easily.

Feel the breath in your chest, breathe in and out a few times, and wiggle your fingers and toes to feel yourself back firmly in your body. You may like to record your experiences in a journal.

Afterwards, you may like to have a special pillar candle that you can light repeatedly in honour of Creiddylad whenever you seek her wisdom or blessing. You may also like to make her regular offerings of flowers upon an altar in your home or in some other sacred space. Remember that any gift or offerings that you make should be heartfelt and always sure to do no harm to the land or any form of life.

Into the Wyllt — Gwyn and Cyledr

There is a final twist to the tale of Gwyn and Gwythyr in the Mabinogion and one that takes the narrative into far darker and more ancient territory. Gwyn overcomes Gwythyr in battle and seizes several of his men — two of these are Nwython and Cyledr, father and son.

In an unusual act Gwyn kills Nwython — whose name could mean great sky or air, or possibly be related to the modern word Nwyth meaning eccentric or odd, and makes his son Cyledr eat his father’s heart, driving him mad. Cyledr whose name is likely to have forest or wilderness connotations, possibly related to Caledonia — the forest of the goddess Dôn — gains the title Wyllt or wild from the experience, denoting his changed status to that of a Wildman or visionary living outside of society. Others in the Brythonic tradition and in the Irish and Scots have similar titles, most famously Myrddin/Merlin who gains the title Myrddin Wyllt during his phase as a Wildman of the woods struggling with insanity and grief inducing visions and prophetic frenzy.

Positioned in a medieval tale, albeit a version of much earlier material, this example of forced cannibalism has disturbing overtones, and can be challenging material in the modern era. However, it is likely to be a tiny scrap of a tale or even a tradition that is far older and taken out of context. There is evidence of Celtic warriors honouring the body parts of their enemies, using them as objects of power, and hearts and entrails may have been used for divinatory purposes, suggesting a belief that the blood and viscera could be used as a gateway to access divine knowledge. Earlier in the Neolithic era there is limited evidence of cannibalism as a ritual act, to consume the power of the ancestors perhaps, and as in later traditions worldwide cannibalism can be understood as an act of honouring a loved one, just as it can be seen as an act of domination by consuming the power of a fallen foe. The names of the father and son, with their implications of either sky and forest, or madness/eccentricity and forest, and given their alignment with the solar/upper world Gwythyr represents suggest something more mythical and symbolic may be taking place than mere vengeance. That they, with Gwyn’s other captives, are held prisoner — presumably in Annwfn — suggests that Cyledr is undergoing an initiatory cycle perhaps, a ritual of descent and ultimate rebirth. In this context Cyledr eating his father’s heart may be understood as consuming his power or his ancestral legacy, and undergoing a prophetic and inspired transformation as a result.

The Wyllt or Wildman

Cyledr’s transformation into Wildman is a recurring motif in the Celtic tradition, where such figures are often carriers of great wisdom and power, and can even represent the spirits of the land and the wild themselves, such as the Scots Gruagach, or the later Woodwose. Sometimes becoming a man of the wild wood is a transition to bring eventual healing along with wisdom, such as when Myrddin Wyllt/Merlin Silvestris goes mad and lives in the wood after the battle of Arfderydd, a tale which in turn was drawn from the Scottish figure of Lailoken. For these characters, their time in the woods represents a merging with its peace and distance from the world of men and its events. Their time there may be full of grief and vision, but it is a healing journey overall. At other times, these beings are spirit or faery in nature, having never been part of the human world rather dwelling alongside it in the remote wilderness. These beings are even more at one with the land itself, dwelling closer to or even in Annwfn at places where it intersects with or overlays the human realm.

That so many wildmen, and sometimes wildwoman figures utter poetry and prophecy in these tales is testimony to the lasting influence of the bardic tradition on the medieval monks who usually recorded them, from either earlier manuscripts or oral lore. As the pagan druid tradition eased over centuries into the Christian era much of the lore was retained in the monasteries and a limited knowledge of the bardic mysteries survived albeit in a disjointed and broken form. Poetry in this sense has its roots not so much in literary endeavour as we understand it today as an expression of divine inspiration where poetry was used to utter prophecy and weave magic. This divine inspiration always has is roots and source in the land. A close relationship with nature and the spirit or soul of the landscape embodied as a goddess or lady sovereignty induces an initiatory sequence where a descent into darkness beneath the earth or a period of madness breaks down the rational mind to allow access to the spirit realm and the inner vision of the soul.

Other than Myrddin, the most famous Bard in the Brythonic tradition was the semi-divine figure of Taliesin, whose name means ’radiant brow’. Taliesin was both the name of a real-world Bard in sixth- century Wales, or at least a series of bards assuming that name, and a mythical magical figure who underwent a magical initiation with the goddess Cerridwen. In his birth and initiation tale Cerridwen is the keeper of a vast cauldron of inspiration, called Awen in the Welsh. In this Cauldron — the same magical vessel described in the poem the spoils of Annwfn and symbolising the womb or heart of the land — is brewed a magical potion which bestows divine inspiration upon those who partake of its magic. This divine inspiration is not merely the ability to generate ideas, rather it is to become in-spirited — to attain the knowledge of all things, of all creation via a merging with the goddess. As such the ability to weave magic, shapeshift into various animals and objects and divine the future and the past all becomes possible.

When taken in the context of the Wildman or Wyllt, Awen or divine inspiration also comes as a result of this communion with the goddess, in this case embodied by the land itself. Complete immersion in nature aligns and bonds them utterly with the sovereignty and soul of the land, via access to Annwfn, the spirit world, for wisdom and renewal. Such a process is naturally mediated by Gwyn as its guardian, allowing access to the goddess and/or her sacred vessel only to those who are worthy of the honour.

Druids and bardic seekers have always used an immersion in either nature or darkness to seek wisdom. Time spent in retreat in wild places to get closer to the gods, sleeping by rivers and using the sounds of nature such as running water, or the movement of wind and clouds for divination- known as neldoracht are ancient practices. Enclosing oneself in a darkened hut under either a cloak, animal hide or with the palm of one’s hands over one’s eyes are also well documented druidic practice- known in the Irish lore as Imbas Forosnai. Similarly, in the writing of Taliesin we see references to being chained in the earth as an initiatory technique, possibly by sleeping in or burying oneself in the earth of a Neolithic burial or barrow mound —often known in the Welsh lore as “Ceriddwen’s court” the ’hollow hills’ of the Celtic Faery lore.

Therefore, in the tale of Gwyn and Cyledr we see an initiatory process afoot under the guise of grisly vengeance — by consuming his ancestral power Cyledr breaks down his mortal self and is able to access a deeper level of reality where connection to the divine becomes possible. Such initiations have always been considered dangerous and even undesirable if they come upon a soul unwillingly — it is certainly not an easy or pleasant process — but to undergo such a journey was considered to have rewards in the ability to commune with the gods and spirits, and access a wisdom and power unavailable to the average person. Such characters were sometimes able to bring these gifts back to the human everyday world for healing and renewal of the whole community. We do not see this end result with regards to Cyledr, and have no means of knowing whether he emerged from the process in the original full tale, but with the characters of Merlin and Taliesin we see these initiates can become mediators and travellers between the mortal world and Annwfn, accessing divine wisdom for the benefit of the mortal world.

Practice: Meeting the Wild Man

Seeking oracular enlightenment, the Awen, from an intimate immersive connection with nature is an ancient and perennial source of wisdom, allowing us to gradually connect with the deeper parts of ourselves and discover we are and have always been intricately bound to the rest of creation and the spirit world. Spending as much time in nature as possible is central to this process, not always an easy thing in the modern world — experiencing for yourself how your consciousness shifts after extended exposure to the land away from the trappings of civilisation is a great teacher in and of itself. It is within this wild isolation that we may most easily become aware of Gwyn and a host of unseen presences upon the land. After a matter of hours our relationship to our bodies as well as to our sense of identity begins to shift, diminishing our stress and external concerns and making us more present and ’grounded’. In such an environment, our ability to heed our inner voice and even begin to work with our inner eye and develop our seership becomes far easier. After longer periods the ability to connect with the land and even merge our consciousness with it begins to happen quite smoothly and gently, especially if we seek and encourage such a communion with the land and its spirit inhabitants within ourselves.

When sitting out deep in nature, try this simple invocation and visionary exercise to seek communion with the Wild Man’s spirit.

First make an offering of song or milk to the land. In several places in Scotland they have what’s called “Gruagach stones” — cup marked stones used for just this purpose. Choose somewhere that feels especially still and wild, and lay your gift upon the earth before retreating to somewhere suitably sheltered but nearby for you to meditate and commune.

Feeling your feet firmly on the ground, preferably barefoot, take several deep slow breaths. Really smell the air, the smell of the soil, of the green leaves, the smell of water or rain in the air itself. What scents come to you on the wind, what textures can you feel against your skin?

Now let your attention turn to within, to your heartbeat and the breath in your lungs. Feel the slow steady rhythm of life within you. Take your time and stay with this awhile, before calling out loud to encounter the spirit of the Wild man. Such figures may come to you from myth and legend or they may be the spirit guardian of the place in which you now sit, don’t over analyse but let the experience unfold as it will.

Try these words or use your own:

“Spirit of the wild man, the divine Wyllt, I seek you in this wild place, let me feel your presence and your wisdom.”

Keep your attention present to the earth beneath and around you and the blood and air within you, and approach the experience in a state of patient acceptance, be open to the Wild Man coming to you as he will, be it in a vision, a series of ideas and thoughts, a felt presence or something else.

They key to this exercise is patience and practice, being immersed in nature as much as possible and being sensitive to the slow subtle shifts of consciousness and presence that can occur.