Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies - Nigel Pennick 2015

Northern Instruments

THE KANTELE, LYRE, AND ALLIED INSTRUMENTS

In the Finnish Kalevala epic, the shaman-craftsman Väinämöinen had a magical genesis. He crafted the first kantele harp out of the skull of an enormous pike fish and strung it with strings spun from a woman’s hair. The original instrument was lost at sea, so Väinämöinen fashioned a new one from the wood of the birch tree. Traditional kanteles are made from a hollowed-out block of wood and have five horsehair strings, but metal strings superseded horsehair when wire began to be manufactured industrially. Later instruments have more than five strings, and a classically oriented concert kantele with key-altering levers like the classical concert harp was devised by Paul Salminen in the 1920s.

Fig. 15.1. Finnish kantele, twentieth century.

The related northern lyre was a bardic instrument in ancient times. This instrument consisted of a flat soundbox connected to two side pieces joined at the top by a yoke that supported the strings. At the lower end of the soundbox was a tailpiece that anchored the strings, which passed over a bridge resting on the soundboard. At Paule, Saint-Symphorien, in the Côtes-du-Nord region of France there is a Celtic stone figure dating from the second century BCE that depicts a musician holding a lyre and wearing a torc round his neck (Dannheimer and Gebhard 1993, 278). In Ireland there are depictions of lyres on Celtic crosses. Remains of lyres from the sixth and seventh centuries have been found in Anglo-Saxon royal burials in England, as at Sutton Hoo and Prittlewell. Gaelic harps in Ireland and Scotland were strung with bronze or brass wire from early times, but it is likely that comparable instruments in Britain and continental Europe were strung with hair or gut.

There are two ways of playing the northern lyre and kantele. One is to play them like a plucked psaltery, with the left hand supporting the body and the right hand picking individual strings. Another way uses a plectrum held in the right hand. This strikes the strings, strumming across all of them. The left hand is held behind the instrument and uses the fingertips to stop strings that the player does not want to sound. In this way different chords can be played. The modern autoharp is based upon this principle. Some versions had a fingerboard between the two supporting arms. This permitted the musician to stop the strings with his or her fingers, as on a fretless instrument such as the violin. The bowed northern lyre with a fingerboard appeared around the eleventh century in Wales as the crwth, and England where it was called a crowd. In Ireland a twelfth-century depiction of this instrument is carved in stone at St. Finan’s church at Lough Currane, County Kerry. In Scotland in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the word cruit (otherwise crott) meant not a northern lyre but the Gaelic harp, a triangular frame harp. From the fourteenth century, the Gaelic harp was called clàrsach in Gaelic and cláirseach in Irish.

A tradition of making one’s own instruments from available materials existed in country districts in eastern England well into the twentieth century. During World War I, soldiers improvised instruments from salvaged materials. In the region around Cambridge, a local instrument, a kind of plucked psaltery called the Anglia harp, related to the Finnish kantele, was made and played. Locally, a hammered dulcimer with single instead of multiple courses of strings was called a harp, even though it had bridges unlike an Anglia harp (Wortley 1938—1975, 20). Most Anglia harps are more basic, without bridges and usually with fifteen strings made from piano wire. The Midwinterhoorns of Twente province in the Netherlands are not manufactured, and all are different, not being tuned to a particular pitch. As with many traditional musicians up to the middle of the twentieth century, it is likely that instruments were tuned relative to the player’s singing voice, rather than standard pitch. Medieval instructions (ca. 1123) exist for casting tuned bells (cymbal), made in sets of eight or nine. They were cast from wax that was divided by weight according to proportions that would produce a diatonic musical scale. They were tuned relative to one another by weight, and not tuned from a determinate concert pitch (Theophilus 1979, 176—79).

DRONES

Traditional instruments originating at various historical times have been used to produce a hypnotic droning sound, such as buzzers, bagpipes, bumbass, Jew’s harp, Scheitholt, Hommel, mountain dulcimer, and hurdygurdy (Old Nick’s birling box). Ritual music predominantly employed the drone as a major element. The Scots word droner can mean a player of the bagpipes, as well as a bumblebee (Warrack 1988 [1911], 147); the same sort of “buzzing-bee” name is given to the Dutch and German drone-based fretted stringed instruments called Hommel and Hummel, respectively. The single-stringed musical instrument devised by Pythagoras, the Monochord, is an image of the cosmos, as Robert Fludd noted in 1617. This instrument, used from Pythagoras onward, became, with the addition of strings, the German Scheitholt and Hummel; in France the épinette des Vosges and épinette du Nord; in the Netherlands, the Hommel; in Friesland, Noardische Balke, and in Norway, the langeleik. The oldest known langeleik comes from Vardalsåsen near Gjøvik in the Oppland district. It bears the date 1524. From mainland Europe, versions of these instruments were taken to the United States. There in the Appalachians it was standardized as the mountain dulcimer. This diatonically fretted instrument is now played widely in European folk music, including by the present author. Another related drone instrument is the string drum, sometimes called a timbrel.

It was also referred to as the chorus and has the French names tambourin á cordes and tambourin Béarnais (Munrow 1976, 33—34). It is a rhythmic drone instrument with tensioned strings along a rhomboidal sound box. The strings are beaten with a stick, and as an accompaniment to a three-hole pipe, it is tuned to the keynote of the pipe and its fifth. The Scots verb to drum means to repeat something monotonously, to drone (Warrack 1988 [1911], 148).

Fig. 15.2. String drum timbrel made by Nigel Pennick, 2009.

THE BUZZER

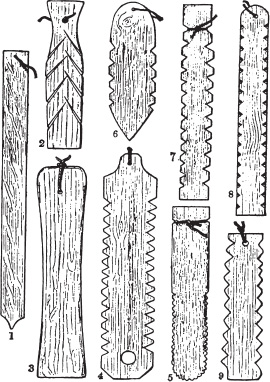

The buzzer is a simple drone instrument consisting of a piece of hard material attached to a string and whirled around to make the sound. It is frequently called by the anthropologists’ name “bullroarer,” though this name was never employed anywhere by its actual users. It is an archaic instrument. One found in 1960 at Kongemosen in Sjælland, Denmark, was dated at around 6000 BCE. It is a piece of bone shaped as a pointed oval, with a hole bored through one end, through which a piece of string could be threaded. Swinging it in the air produced a humming sound. This instrument is simple to make, and disposable. The Danish word for it is brummer; in English the names were mainly bummer, hummer, humming buzzer, or buzzer. Various designs were collected in England in the nineteenth century and, according to the custom of the time, classified by county. Haddon wrote in 1908 that the ends were usually square, but the string end could be rounded; the sides could be serrated or simply notched along both surfaces of each side (Haddon 1908, 278).

Fig. 15.3. Buzzers from England. The Library of the European Tradition

In the 1850s the young weavers of Belfast liked playing what they called the boomer or bummer, described as “an oblong piece of wood, pierced with two holes, and serrated all round” (Haddon 1908, 284—85). The Scottish bummer or bum-speal was described in 1911 as “a thin piece of serrated wood attached to a string,” swung to give a booming sound. In Scotland the tambourine was called a bumming duff. The Scots word bum means “to drone, as in a bum note, a note misplayed in a tune” (Warrack 1988 [1911], 62). Haddon’s informant in northeastern Ireland stated that once when, as a boy, he was playing with a boomer an old country woman said it was a “sacred” thing (Haddon 1908, 283—84). In the Schwarzwald of south Germany, the instrument was called Schlägel or Brummer. Sometimes, one was attached to the end of a whip and whirled round at ceremonial events; this is called a Schwirrholz (Seidel 1896, 67).

In Scotland the instrument is also known by a name that associates it with thunder; generally as a thunder-spell, and in Aberdeen as a thunderbolt (Haddon 1908, 280—81). Alice Gomme in her Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland gives this definition:

Thun’er-Spell. A thin lath of wood, about six inches long and three or four inches broad, is taken and rounded at one end. A hole is bored in that end, and in the hole is tied a piece of cord between two and three yards long. . . . It was believed that the use of this instrument during a thunderstorm saved one from being struck with “the thun’er-bolt.” (Gomme 1894 and 1898, II 291)

The Scots dictionary compiler Alexander Warrack describes the thunder speal being “whirled round the head to mimic thunder” (Warrack 1988 [1911], 612). Gomme noted that the more rapidly the instrument is swung the louder is the noise. Haddon noted that when swinging more rapidly, the high note of a buzzer passes into a low harmonic. In Galicia this tuning effect was called bzik (Haddon 1908, 285).

Related to the buzzer is the sneerag, made of one of the larger bones of a pig’s foot connected to two worsted strings, used to produce a snoring sound (Warrack 1988 [1911], 540). A wooden version is the “buzz,” made from a small, flat, rectangular piece of wood through which two holes are pierced. A long, continuous piece of string is passed through the holes and tied in a loop. The loops are held in the two hands, and the wood is swung around to twist the string. Then the hands are strongly and steadily drawn apart, causing the wood to spin rapidly, producing a buzzing sound. The momentum makes the string twist itself up again, and it can then be pulled, reversing the spinning “buzz” (Haddon 1908, 284—85).

ROTATORY RATTLES, WALDTEUFEL, JACKDAW, AND ROMMELPOT

Another type of traditional noisemaker consists of a handle with a circular ratchet at the top, onto which is pivoted a framework holding flexible wooden slats that overlap the ratchet. When the instrument is whirled around, the slats interact with the ratchet to make a rattling sound. This is the Rärre used by Devil guisers in the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht tradition of south Germany. Rattles of this sort were used as a warning of poison gas attacks in World War I. In his exposition of the buzzer, Haddon describes “a child’s toy well known in Germany as the Waldteufel ” (Woodland Devil). He described it as a small cardboard cylinder, open at one end and closed at the other like a drum. To the middle of the drum a horsehair or fiber was fastened, and the other end was tied to a piece of wood. The wood at this spot is coated with resin to produce a grating sound that was transmitted along the fiber, the cylinder acting as a resonator (Haddon 1908, 284). A related English instrument was the jackdaw, which was made of about an inch of the top part of the neck of a wine bottle. Over this was stretched a bit of parchment, which was tightly tied under the projecting rim of it. A long horsehair, with a knot at the end, was then put through the parchment, the knot being inside the neck. By wetting the forefinger and thumb and drawing the horsehair between them, the player could produce sounds by moving the hand rapidly or slowly or in jerks.

A related friction drum played in the Low Countries is known by its Dutch name, rommelpot (rumble pot), from the Dutch verb rommelen, meaning “to produce a low, dull noise, to rumble.” In Germany it is called Brummtopf (Munrow 1976, 34). The sound of the rommelpot is produced by the vibration of a membrane stretched tightly across the neck of an earthenware pot, jug, or soup bowl. Traditionally, the membrane is made from the bladder of a pig or cow, and a wooden stick is inserted through the middle. Rubbing the stick with moistened fingers produces the sound, and variations in pressure control the pitch. The sound was considered unearthly or diabolical, especially when the pot contained dried peas or was half-filled with water. In Flanders the rommelpot is an instrument played traditionally on various festive days (De Hen 1972, 105—10). In Brabant there is a traditional dance called “Rommelpot,” which of course should be accompanied by the instrument. Like the bodhrán (see below), after almost falling into disuse the rommelpot was given a new lease on life through the efforts of Paul Collaer and Felix van Eekhoute. There is an unbroken tradition of playing it in the Belgian village of Kessenich.

THE FRAME DRUM

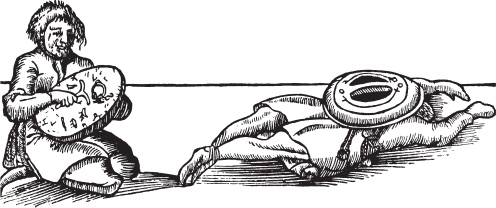

The frame drum is well known as the sacred instrument of the shaman. It has a mystique because it enables the shaman to enter altered states of consciousness and practice soul-flight (Old Norse hamfarir). It was rare in Europe outside areas where shamanism was practiced.

In nineteenth-century Cornwall a sea witch called Kate “the Gull” Turner possessed a frame drum or “tambourine” with which she performed divinations. Orientation of the drum according to the cardinal directions appears to have been part of the ritual. In Britain and Ireland the frame drum was traditionally seen as a ritual instrument and played only during the rites and ceremonies on May Day and Hallowe’en, and by the Wren Boys at Midwinter. In the west of Britain and Ireland, the frame drum appears to have been identical with an agricultural implement called the wecht, wight, or dallan, used for winnowing, separating the chaff from the grain (Evans 1957, 211). Structurally, the implement is like a sieve, but instead of having interwoven cords to screen out large from small objects, it has a base made from an animal skin, so it can easily double as a drum. An English frame drum in a rare photograph taken of Jack-in-the-Green at a traditional May Day performance in Oxford in 1886 is much larger than a wecht or a bodhrán.

Fig. 15.4. Sámi shamans’ drums, Finland, from Johannes Schefferus’s Lapponia (1673). The Library of the European Tradition

An indication of the tradition of calling upon things to grow is in the Scots expression “deaf grain,” meaning grain that has lost the power to germinate (Warrack 1988 [1911], 127). The name of the Irish frame drum, bodhrán, is derived from the Old Irish word bodhar, meaning “deaf” or “haunted” (James 1997, 78). Materials matter both acoustically and magically. For the bodhrán, makers prefer to use goatskin or deerskin, giving a good sound, but calf, sheep, donkey, and greyhound skins were also used to stretch across the frame (James 1997, 80). Goatskin is considered to produce the authentic bodhrán sound (Driver 1994, 4). H. C. Agrippa commented that a drum made from wolf ’s skin causes a drum made of lambskin not to sound (Agrippa 1993 [1531], I, XXI). With both the shaman’s drum and the bodhrán, the skin is stretched across the frame with its outside facing outward; that is, the surface that is played. The bodhrán frame is made of ash, bent green and lapped at the joint (McCrickard 1994, 20). It has crossbars at the back made of wood or metal, which stabilizes the frame and provides a handhold. Some shamans’ frame drums also have crossbars, while others have a metal ring suspended by thongs, or a rod carved into a humanoid form.

In former times the bodhrán was associated with the west of Ireland, parts of the counties of Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary (McCrickard 1994, 21). At one time it was played only during ritual performances by the Wren Boys on St. Stephen’s Day (December 26), in a rite that involved hunting and killing a wren and parading it from house to house. In the 1960s it was played notably by Seán Ó Riada (1931—1971) and adopted by other Irish traditional musicians as a viable instrument for music at all times. In 1986 the Irish playwright J. B. Keane wrote a play titled The Bodhrán Makers. In the early twenty-first century, the Irish bodhrán is widespread among traditional and folk musicians in Ireland, Great Britain, and the United States.

THE CLAPPERS

It was formerly customary to make percussive sounds at Eastertime. There is a German tradition of hitting walls with hammers in springtime (Sonnenvogelklopfen). In Wales children used clappers to make a noise to alert householders to give them eggs for Easter (clepio wyau’r pasg). There are two known forms of egg clappers from Wales. The simpler clapper is a wooden instrument shaped like a cooking spatula to which two other flat pieces of wood are tied tightly by strings threaded through two holes. When the handle is shaken, the tied-on pieces clap against the flattened end. A larger kind of clapper is a wooden board with a hole at the center through which a handle protrudes. A double-headed wooden hammer is hinged into the top of the handle, and rapid movement makes the hammer swing back and forth, hitting the board (Owen 1987, 86). There is an English saying, “to go like the clappers,” derived from the speed with which the clappers can be played. Related in structure is the Lithuanian skrabalai. The instrument consists of a trapezoidal wooden trough hollowed out from a block of oak or ash, with wooden or metal small clappers hung inside. The skrabalai is shaken so that a clapper knocks against the side of the trough, making a hollow clapper sound. It can also be played as a drum using sticks.

BONES

Bones make good percussion instruments. A pair of cow ribs rattled together was a traditional instrument everywhere there were cattle. Rib bones were called knicky-knackers in seventeenth-century Britain, where, not surprisingly, they were associated with butcher-boy rituals and pastimes. It was traditional for butcher boys to serenade newlywed couples with marrowbones and meat cleavers. “Formerly, the band would consist of four cleavers, each of a different tone, or, if complete, of eight, and by beating their marrowbones skilfully against these, they obtained a sort of music somewhat after the fashion of indifferent bell ringing. When well performed, however, and heard from a proper distance, it was not altogether unpleasant. A largesse of half-a-crown or a crown was generally expected for this delicate attention. The butchers of Clare market had the reputation of being the best performers” (Larwood and Hotten 1908, 358). An illustration of this from Chambers’s Book of Days (1869) is shown in figure 15.5.

Fig. 15.5. The Butchers’ Serenade, 1869. The Library of the European Tradition

The bones, smaller than full cow ribs, are a folk instrument that in the nineteenth century became associated with blackface minstrels. But they were never exclusively a minstrel instrument, for they are played in performances and pub sessions of traditional music of Britain and Ireland. Two or more bones are held loosely in one or both hands, which then are shaken in rhythm to produce percussive sounds. Sometimes they are played by step dancers in accompaniment to their dance steps. Bones players consider the best material to be whales’ bones, very hard yet easily worked like wood (Driver 1994, 25).

BELLS

Bells are closely connected with religious rites and ceremonies, as well as being an adjunct to dance and as a warning in transport. They signify and amplify the presence of desirable spiritual powers, while suppressing unwanted intrusions. Bells transmit the virtue of the metal of which they are made. In ancient Greece resonant metal instruments were called “the bronze” (chalkos). A scholiast of Theocritus remarked that the chalkos was sounded at eclipses of the moon “because it has power to purify and to drive off pollutions.” Sounding the bronze in ancient Rome was instrumental in rituals. Ovid noted that the annual visits of the spirits of the departed to their former homes were brought to an end by sounding a bronze plate and ordering them to leave.

The particular resonance of a bell depends upon the material it is made of, its dimensions, and its shape. Its sound is a manifestation of these qualities. Early bells were made by bending sheet metal to shape and riveting the join, and cowbells are made in this way now. This kind of bell is still hung around the necks of herd animals to ward off evil. The other kind of ancient bell is the spherical bell used from early medieval times on horse harness. Bells like these are similar to the ceremonial bells worn by some shamans, guisers, and Morris dancers. They ring as the performer walks, runs, or dances. Town criers in England ring a handbell to attract people before making their official announcements. From the early medieval times, large church bells were cast in foundries. It is not known whether bells were introduced into northern Europe by the Romans or by Christian missionaries, but the clergy of the Celtic Church certainly recognized the sanctity of bells. Bells that had belonged to revered priests were preserved in ornate reliquaries. They were no longer capable of being sounded, but considered magically powerful objects in their own right. The bell of the ninth-century Irish priest, St. Cuilleann, is a typical relic used for ritual purposes. For many years it was kept in a hollow tree at Kilcuilawn at Glenkeen, County Tipperary. In the eighteenth century it was taken out so that oaths could be sworn upon it. Bells like this were in the keeping of dewars, hereditary relic keepers, and handed down through the generations in families. For example, on the island of Inishkeel, County Donegal, the O’Breslan family kept the Bell of St. Conall. In the Christian tradition, bells were baptized and given names.

BELLS IN HORSEMANRY

The Scots ballad “Sir John Gordon,” collected by John Ord in his Bothy Songs and Ballads, tells how Sir John encountered the Queen of Faerie and was taken away to the Otherworld where he had to serve her. The horse ridden by the Queen of Fairyland was bedecked with a particular number of bells:

Her gown was o’ the green, green silk,

Her mantle o’ velvet fine,

And from the mane of her milk-white steed

Silver bells hung fifty and nine.

(ORD 1995, 423)

In England it was a medieval custom to give a golden bell to the winner of a horse race. An annual race with this prize was run on St. George’s Day (April 23) at Chester. Racing for a bell led to the expression for being the winner, “bearing off the bell” (Larwood and Hotten 1908, 174—75). The Carter’s Health, noted in Nuthurst, Sussex, England, 1812—13, refers to the custom of “the wild stud,” and the best mare.

Of all the horses in the Merry Green Wood

’Twas the bob-tail mare car’ d [carried] the bells away.*4

(CLARK 1930, 797)

In the British Isles, packhorse gangs were a common form of transport before the construction of turnpike roads, canals, and railways. A number of horses (a train) proceeded in single file along unpaved track-ways or across open moorland along customary routes. Each horse in the train was fitted with packs or panniers. The train was led by a lead horse that was fitted with bells. In 1790 Thomas Bewick noted that the packhorses,

in their journeys over the trackless moors . . . strictly adhere to the line of order and regularity custom has taught them to observe; the leading Horse, which is always chosen for his sagacity and steadiness, being furnished with bells, gives notice to the rest, which follow the sound, and generally without much deviation, though sometimes at a considerable distance. (Bewick 1790, 14—15)

The bells on the lead horse also gave warning to other travelers that a packhorse train was coming, so they could take avoiding action. According to the mythos of the Scottish Horsemens’ Society, taught to new members at the time of initiation, the names of the first mare and stallion were Bell and Star. There was a bell on her brow and a star on his brow (Rennie 2009, 111). This, of course, is symbolic. The bell and the star are both symbols of guidance. The lead horse’s bell guided the packhorse train, while the leading star whose position in the sky never changes allowed navigation at sea and on land.

THE NORTHERN HORNS: LUR, NEVERLUR, BARKLUR, AND MIDWINTERHOORN

Surviving ancient horns from Ireland, circa 500 BCE, were made of bronze. Some were up to eight feet long, made from smaller pieces riveted together. The largest ones were side blown. A similar Scandinavian horn was the lur (cf. Old Norse luðr, a “hollow log”). The earliest known instruments came from the Bronze Age and were actually made of bronze. There were once two ceremonial horns bearing figures and runes, fashioned out of sheet gold and dating from the early fifth century CE, which were found at Gallehus, north of Møgeltønder in Jutland, Denmark, in 1639 and in 1734. As they were not intact when found, and have since been destroyed, it is not certain that they were musical instruments, but the banded construction resembles known musical horns made in Scandinavia and the Netherlands from various species of wood.

The most well-known Bronze Age lurs are the Brudevælte lurs, discovered by Ole Pedersen in 1797 in a bog near Lynge in North Zealand, Denmark. They are different from the Viking Age battle horns found in Germany, Denmark, and Norway, which were straight, end-blown wooden instruments about a yard long, bound with willow withies. Bronze lurs have an S-shaped curve reminiscent of aurochs’ horns. Battle horns known from sagas had the same function as bugles in later military use. A lur was buried in the Oseberg ship burial of a Norwegian noblewoman dated 834 CE. It was a conical horn enclosed in a richly decorated oak box, one of the earliest musical instrument cases known. Later medieval horns made of pine or fir bound with birch bark (neverlur) were used by peasants in Scandinavia. The barklur or barkhorn (Finnish touhitorvi) was made from spirally wound strips of alder, ash, spruce, or willow.

Similar in construction to the ancient horns described above, the Midwinterhoorn is an instrument used in ceremonial tradition in the Dutch provinces of Overijssel and Twente and the Achterhoek district of Gelderland province. As its name suggests, it is played outdoors around the winter solstice between the beginning of Advent (December 6) and Driekoningen (Twelfth Night) January 6. It is a wooden instrument of archaic appearance, with a special form of construction. They are overblown horns with no finger holes, producing natural harmonics. There are two kinds of horns made according to this technique: natte hoorns (wet horns) and droog hoorns (dry horns). Dry horns are not traditional. They are a modern version of the Midwinterhoorn, with the wooden halves glued together. Traditional Midwinterhoorns are made usually from curving branches of alder or birch trees, measuring from about four to six feet (1.2 to 1.8 m). The longer the horn, the easier it is to play higher notes. A horn made of alder is called an elsenhoorn, and one made of birch is a berkenhoorn. The narrow end where the mouthpiece is set can measure from one to two inches (25—50 mm), and six inches (150 mm) at the wide end.

The maker of the natte hoorn shapes the branch, then puts it in a well, where it is left to soak for a period. When the wood has soaked sufficiently, the horn maker cuts off the bark using a draw knife. When it is thoroughly wet, it is hauled out and split longitudinally. The two halves are hollowed out and made smooth, and a hole is drilled in the narrow end to take the mouthpiece. When ready, the two halves are put back together. Bulrush leaves are put in the join, and the horn is lashed together tightly with brummel, willow, or bramble (blackberry) stems coiled round the horn six times, their ends being tucked beneath the last coil. Then wooden wedges are hammered under the bindings from the narrow end of the instrument. There are at least six bindings on each horn. Then the Midwinterhoorn is put back into the well until the bulrush and bindings have swollen in the water and made the horn airtight. The wedges are hammered farther in, and the hap (mouthpiece) is made of elder wood and fitted into a hole at the narrow end of the horn.

Midwinterhoorns are not tuned to any common pitch, as they are essentially solo instruments used in calling and answering when played with others at a distance. The Midwinterhoorn player holds the horn laterally, though it is blown straight down the tube. The shape of the mouthpiece allows it to be blown straight down the tube, although it appears to be across like the classical flute. Some ancient images of horns resemble those made today, and many medieval images of celestial horn blowers show lateral blowing like the Midwinterhoorn, such as in the early fourteenth-century wall painting in Schleswig Cathedral, Germany, of a horn-blowing woman riding a tiger, possibly an image of the goddess Freya. The natte hoorn is blown wet, and it is customary to blow the Midwinterhoorn over a well. This amplifies the sound of the horn. When the horn freezes in winter, it produces a particularly brilliant sound that is said to enhance the fertility of the soil and promote an abundant harvest (Montagu 1975, 71—80; Thijsse 1980, passim). The Midwinterhoorn may have survived in this region because Twente province was a Catholic enclave in a Protestant country. The Calvinist prohibitions on music did not reach there, and during the sectarian wars of religion it was used as a warning signal of the approach of Protestant military forces.

PRACTICAL AND MAGICAL MATERIALS

Writing “on sound and harmony,” H. C. Agrippa noted that some sounds go well together, while others can never be harmonious. One of his examples was that strings made of sheep’s gut can never be tuned together with those of wolf’s gut. Although this may not technically be true, it clearly was a tradition among instrument makers that certain materials would not work with certain others, so they were avoided (Agrippa 1993 [1531], II, XXV).

Traditional stringed instruments need to be made from combinations of particular woods if they are to sound good. The back and sides of instruments such as fiddles must be made of a stiff and resonant wood, such as ash, beech, maple, sycamore, walnut, and willow, or rarer woods from fruit trees such as pear and cherry. The main soundboard of the instrument must be made with a thin, stiff, strong wood, cut on the quarter. Conifer wood is ideal, and pine, cedar, fir, and spruce are favoured. The neck must be made from a strong, durable wood that can be carved freely, such as sycamore, maple, or beech.

Some ancient ballads and sagas give material descriptions of how to make things. The Finnish Kalevala details the materials of the kantele made by Väinämöinen from the wood of the birch tree, the materials of the tuning pegs, and the strings. In Ireland Cormac’s Glossary (ca. 900 CE) tells that the instrument called the timpán was made of sally wood, and the tone of its bronze strings was soft and sweet. The timpán, upon which the ceol sidhe heard by St. Patrick was played, appears to have been a kind of lyre or psaltery played with a quill plectrum. “The willow has a mystery in it of sound,” wrote Lady Wilde, and according to Irish tradition the harp belonging to the eleventh-century King Brian Boru was made of willow wood (Wilde 1887, II, 117). Some Perchtenlauf bands in Austria, the Holzmusik, play special wind instruments made entirely from wood, some of which are versions of those customarily made from brass.

DISORIENTATION BY SOUND

One can be disoriented by noise, and in Scots there is the word to describe it: gallehooing, a stupefying senseless noise (Warrack 1988 [1911], 202). “Nor do they want music, and in a strange manner given them by the Devil. . . . Where everyone sung what he would, without hearkening to his fellow; like the noise of divers oars, falling in the water,” wrote Ben Jonson of the witches in his notes to The Masque of Queens (1609). In the early twentieth century, the Dadaists produced the same chaotic, disorienting effect with their “simultaneous poetry.” There is a tradition of disempowerment of spirits by music; for example, the seventeenth-century English tune “Stand Thy Ground Old Harry” was said to ward off the Devil.

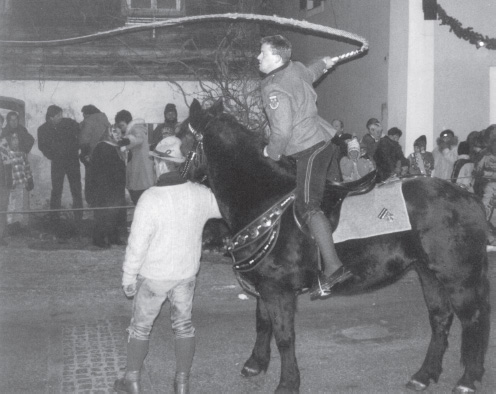

Evil spirits are believed to be frightened away by sound, as in the German custom of the Richtfest, topping out the roof of a new house. The hullabaloo (Hillebille) is made with hammers, chains, shouting, and singing and is intended to drive away any evil spirits that would bring bad luck to the new house (Bächtold-Stäubli 1927—1942, III, 1564). Noisemaking is also part of the “charivari” or “skimmington,” a near-riotous gathering in public to express disapproval of an unpopular individual. In England this is the “tin can band,” or “rantantanning.” In Germany it is called Katzenmusik (a “caterwaul”), with people banging improvised instruments such as cooking pots and pans, and is intended to drive away evil spirits or run people out of town. In Austria horsemen crack whips at the New Year to purify the air from evil. Noisy fireworks let off at New Year all over the world can also be viewed as driving away the evil spirits from the celebration of the new beginning.

Fig. 15.6. Whip-cracking on horseback at New Year, Pongau, Austria.