Speaking with Nature: Awakening to the Deep Wisdom of the Earth - Sandra Ingerman, Llyn Roberts 2015

Wild Western Hemlock Tree - Llyn

Wild Western Hemlock Tree and Cottonwood Tree

When I was a child growing up in New Hampshire, my favorite tree was the Eastern hemlock, or hemlock fir tree. I loved this delicate tree with its miniature cones, soft needles, and limbs that sloped like draping shawls.

The Hemlock Tree of the Pacific Northwest where I now live is very much like its Eastern cousin in that this dainty tree is slow to grow, loves the shade, and can weather tough winters.

Western Hemlock was integral to early tribal life on the Olympic Peninsula. The wood of the Hemlock Tree was carved into utensils and everyday items, its bark was used to make dyes that colored baskets and wool, and the cambium inside the bark that black bears love to eat was also a favorite food of the native people of these lands.

![]() Imagine lying on your back on a cushiony bed of conifer needles in a lush temperate rain forest. Breathe in the cool, moist air, then expel a long steady breath. See the steam release with your breath and evaporate into the air.

Imagine lying on your back on a cushiony bed of conifer needles in a lush temperate rain forest. Breathe in the cool, moist air, then expel a long steady breath. See the steam release with your breath and evaporate into the air.

Gaze up at the grand Wild Western Hemlock Tree. Take all the time you like to open your heart and sense the spirit of this nature being.

When you feel ready, imagine yourself now lying on the earth in a different location—beneath a conifer sapling in a new forest that is growing up from clear-cut land.

Note how your body feels resting on the earth. Take in a smooth and steady breath. Smell fresh life all around you. Listen as little birds hop through the underbrush plucking thimbleberries.

The Hemlock branches above are feathery light. Imagine reaching up and touching supple green needles. Now, tug on a tiny limb. In your mind’s eye watch the tree jiggle as if giggling from a tickle, as the thin, limber bough bounces right back.

Take a moment to open your heart to the baby Hemlock Tree.

I always notice that the young Wild Hemlock appears limp and fragile next to its perky neighbor, the fir tree that people plant on Northwest tree farms. Yet like the wild and wispy willow that digs fast into the rocky soil of the Hoh River gravel bar, Hemlock is anything but frail.

Tenacious roots, pliable leaves, and flexible limbs anchor willow through violent winds that sweep up the Hoh Valley from the Pacific Ocean. Similarly, Western Hemlock endures savage weather from the untamable Pacific. Like the tender-leafed willow, soft-needled Hemlock is unsuspectingly tough, rooted, and supple so harsh weather filters through.

I’ve never seen a willow or a Western Hemlock growing alone; they are protected in community. However, when trees are cut the forests are divided and high winds ravage the unnatural open spaces. More trees fall. This blowdown happens all the time at the edge of clear-cuts.

Like Hemlock we benefit in being with others. It helps us to weather difficulties if we’re not all alone. Hemlock encourages us to stay grounded and flexible as life’s gales blow, so turbulence can pass through with less harm.

Being amenable on the surface yet unshakable and protected at the core has helped indigenous groups hold on to their traditions during times of persecution. This is true among the beautiful people of the small Republic of Tuva on the Asian steppe.

Tuvan folk ballads and the haunting whistling sound of its throat singers are admired the world over, yet it wasn’t long ago that Tuva’s shamans were shot to death or burned alive. Old traditions fostering harmony with nature, community, and natural healing were outlawed. Shamanism went underground, the sacred held secret until the Soviet regime collapsed. Tuvans and other Eurasian indigenous groups, like so many of the world’s first peoples, camouflaged or concealed ancient knowledge and banded together to weather painful change.

Few of us know what it’s like to hide what we believe in and hold sacred, for fear of death. The closest we may come is in hiding who we are to avoid being judged.

As one instance it’s not that unusual today for an allopathic physician to also do some form of energy or even shamanic healing, and psychics and mediums—living people who see and talk to the dead—draw thousands of followers. Just decades ago none of this was happening. What seems normal now was practiced in quiet by healers and spiritualists until society grew more accepting.

This is a good example of Hemlock medicine, which keeps the wisdom fire burning while surface winds are choppy. When used for firewood Hemlock burns strong and silent and its embers last a long time.

The Mayans and the Quechua people of Central and South America also shrouded their teachings to protect them when the Spanish invaded. In 1991 the Quechua finally began releasing long-held spiritual wisdom and acknowledged that a prophesied era is upon us; the world is at a precipice and humanity is ripe.

Winter gusts eventually smooth out along the Hoh River Valley. The seemingly never-ending rain gives way to summer’s warmth, and Hemlock grows straight and tall toward the blazing sun. In this more conducive climate, Hemlock calls to us each in her divinely feminine voice: “Stand tall with me now. If your soul is still hiding, it is time to come out.”

“But, but, but, oh dear Hemlock,” we may stammer.

“Stand tall with me now,” murmurs the gentle tree being with branches that dangle like soft wings.

Western Hemlock and sitka spruce are the trees we most often see in the Hoh Rain Forest. It takes hundreds of years for Hemlock to fully mature, towering to heights of three-hundred feet and spreading to widths of twenty-three feet. Standing in the presence of these trees inspires awe.

Like the Western Hemlock, it takes time for us and for our species to evolve, but we must all grow up sometime and the signs abound that now is the time.

In the global arena, and for many of us, the winds of uncertainty still toss. Bridging any new season or change is a letting go of one way to another, the dissolving of what was, just as winter snow and ice melt to warm and water the new life of spring. If we live in a four-season climate, we might easily imagine wanting to hold on to summer.

Imagine trying to hold on to winter. This may seem silly. Even before the end of a long, dark, cold winter, everyone is ready for spring. Yet imagine if winter were the only season you knew. If you lived in a winter world, as the snow receded on the mountains and in the valleys, and the ice melted in the rivers and lakes and ponds, you would feel that your world was literally falling apart. And it would be.

As the ideas that hold our reality structures in place give way, our world appears to fall apart. The old stories do not fit anymore, and new stories have not yet fully formed.

The Western Hemlock of the Hoh Rain Forest dies, yet never dies. This tree can stand deteriorated for decades while birds, insects, and small mammals make it their home. When the tree eventually falls, it opens up the space for the sun to nurture other plants and then it is host to microbes, insects, and fungi, such as bright yellow chanterelle mushrooms. These all eventually reduce the trunk to humus, which is seeded by forest animals. From the seeds grow new trees.

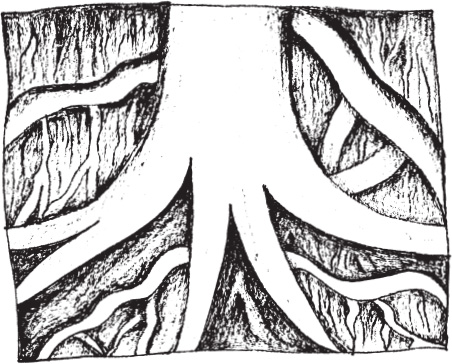

Imagine strolling through a richly scented Hemlock forest. Look at the Western Hemlock’s narrow trunk columns. Some of these tree giants lift off the ground at their roots as if they’re walking, like the race of tree beings called ents in J. R. R. Tolkien’s fantasy world. These mammoth Hemlock beings sprouted from fallen nurser logs, which nourished the saplings that literally grew on top of the mother Hemlock while she receded back into the earth.

Hemlock advises: “Anchor now. At the same time be as flexible as my limber limbs and Mother Hemlock, who surrenders to new life. Let go and trust.”

The life cycle of the Hemlock shows that beauty often grows from death; the dying times feed and inspire a surge of new life. Death and darkness have their own beauty and intelligence, and like the Hemlock, we are dying and growing all the time.

When I relocated to the Northwest six years ago, I was so drawn to the intriguing Western Hemlock with its fancy telltale tassel, dangling as if weighted by an invisible ornament from the tiptop of its tall growth. I had an amazing feeling of déjà vu in looking at Hemlock; this nature being and I were friends.

Was it the time I spent as a child lying on the earth under wispy hemlock branches during New England snowfalls—looking up through white-dusted needles and cones as snowflakes drifted down to melt on my cheeks—that induced such strong sentiment for this conifer? This is ever more poignant as Northeast hemlocks die of woolly blight.

The Celts have a beautiful phrase that describes unexplainable affinities—anam cara, meaning “soul friend.”

Most of us have known someone we felt immediate kinship with upon first meeting. And everyone has heard the term “soul mate.” We may even have asked ourselves: “Where is my soul mate? When will my other half find me so we can transport each other to unending bliss?”

If you’ve ever discovered a soul mate (there are many) and tried to live with that person in twin-soul rapture, your reality likely did not match your dreams. The true gift of special connections, which is to help each other evolve and grow so we can fulfill what we were born to do, is often lost to modern culture because we have too many superficial ideas and expectations for what a soul friend is and must be.

We also overlook the amazing anam cara, or soul kinship, people can have with nature.

Take a moment right now to think on your own favorite tree in childhood, an indoor plant that you speak with and listen to as it speaks back to you, a cat or dog that came to you serendipitously and whose spirit you recognize, a foreign landscape that is hauntingly familiar, or the uncanny feeling you get when sniffing an iris or other flowering plant—some aspect of the natural world with which you feel an unusually deep or unexplainable connection.

The striking sentiment that arises with certain nature beings is soul recognition, anam cara.

All indigenous shamans I have met revere the land they were born on; this is the source of their power. Years ago my friend and colleague Bill Pfeiffer and I traveled in Siberia with a fierce shaman woman named Ai-Tchourek who insisted we visit her homeland. This woman’s connection to home moved me. Surprisingly, though I had never walked these lands, they felt familiar. I knew the river and lay of the taiga (tundra forest). Feeling so at home in these lands I had never known before was a beautiful experience.

When I was a child, my love for the Hemlock Spruce opened me to sacred kinship with nature. Hemlock and all nature beings invite us to explore special bonds with the land, water, wind, trees, stones, animals, and so forth. Through these relationships we open to magic and love, bridging the chasm between people and the natural world. Our reality expands.

Do we draw nature beings to us, or do they call us to them?

Did we live a past life on lands that speak to us?

If a child tracked her feet while riding a bicycle, the little feet would get caught up in the bike pedals or the child would be looking at the feet instead of where the bicycle was headed; either way the child would fall off the bike.

Hemlock Tree suggests: “To engage the mystery, become the mystery. Think or even care about it too much and you fall out of it.”

I have found that the best way to understand soul kinships with nature, or with people, is to explore them with feet on the ground and an open heart. In tracking for animals among Western Hemlocks in the Hoh Rain Forest, I am learning to identify signs—prints, tree markings, dung, nipped twigs, items in an animal’s scat (berries, hair), and so forth. I notice how fresh or old the prints appear and scan the area with my senses and intuition, seeking clues and tucking them away in memory. I find that tracking is an art of invisibility—blending into the environment, being precise in what I observe and sense, and staying open and not jumping to conclusions. It involves thoroughly enjoying a journey that may never fully reveal.

Track this way in the Olympic Mountains and you may bump into an elk. Regardless, you will walk the forest freshly, full of wonder.

As much as we sometimes think we know why animal, person, stone, tree, or land shows up in our life, magic increases when we let go of the search and immerse in the unfolding. This also opens us to know anam cara with everything and everyone, without judgment about how that expresses.

Sacred kinships stir the soul awake, reminding us that we are one source, never separate. They reconnect the collective spirit of people and nature.

Ripe to help us discover who we are, Hemlock tells us the hiding times are over; it is time for the soul force to shine. We simply have to trust that the world is headed there, too.

![]() Practice

Practice

Hemlock Tree teaches about the internal wisdom fire and how to flow with difficulty, as well as into who we truly are. You will find below a way to embody these teachings and make them available in daily life. No special music or preparation is needed.

Wherever you are right now (ideally outside with bare feet, though anywhere is fine), stand tall like a healthy tree.

Imagine your roots extending deep into the earth. Feel the sun’s warm caress. Sense your trunk, soft needles, sloping branches, and tiny conifer cones.

Take a nice deep breath. Then exhale.

Become Hemlock or a tree in your locale, or one with which you feel a special bond. Feel this tree’s spirit. Sense your soul kinship with this nature being.

Take another refreshing inhalation, breathing in wonderful Hemlock (or other tree) qualities. Then exhale and relax.

For several moments simply breathe naturally while feeling the tree’s goodness.

Take all the time you like.

When you are ready, let go of being a tree. Continue to sense goodness, yet just be you. Sense your essence, soul, or sacred center, whatever notions or words work for you.

Where in your body is this feeling strong? Where does the deepest part of you reside?

Take time to sense what you note.

When you have located this place where your essence feels strong, take a deep breath here and touch your sacred center. Allow this to be palpable.

Take another refreshing breath in, and then release a relaxing breath.

Now firmly place your feet at the same time onto the floor or on the earth. Or jump if you are able, landing both feet onto the earth at once. As you do feel your roots. Dig in fast, anchoring into the earth.

Take time to note how it feels to be secure and sturdy, your sacred center rooted deep in the earth.

How do you feel?

Still standing, let a light feeling come over you. Allow your body to feel loose and weightless as you gently move. Imagine you are a rag doll coming to life, stirring fluidly. Move and flow intuitively from your center. You may feel a ripple or buoyant quality to the air as you slowly move, as if in water. Move your feet, too, but don’t lose that feeling of being rooted—centered in yourself and the earth with a light, limp body.

Follow your impulse, moving in whatever ways feel right. Try making arcs and circles with your arms and legs, allowing your torso and head to flow and bend and spiral, unfolding in a joyous dance. Just as spiraling winds and water cleanse, we can wash and spin away the tendency to be rigid and fearful in favor of flowing more from the heart.

Move for as long as you like or feels comfortable. Indulge slow movements first, and then you might like to explore how it feels to move a little faster as the wind howls through tree branches and leaves.

Then move slowly again.

Enjoy moving until you come to a natural place of rest.

To close, consider taking a leisurely stroll while feeling both anchored and fluid. As you walk, and at any time when you find yourself among them, study how the trees move. Watch them intently, and observe the fluttering of leaves and the sway of boughs and even trunks, which can bend dramatically in ways we barely detect.

What do you notice?

Let yourself go to mimic and express as the trees do and as you did in the movement practice above.

What do you feel?

Hemlock says, “Breathe with us and move with us until you move as us, soul friends. There’s a world beyond words we are waiting to share.”