Bird Magic: Wisdom of the Ancient Goddess for Pagans & Wiccans - Sandra Kynes 2016

Come from Her: Life-Giver and Creatrix

The Practices

The first aspect of the Goddess is her role as life-giver. However, this encompasses more than giving birth; it includes nurturing, sustaining, and protecting life. Following the nurturing and protective ways of the Great Mother Goddess, Neolithic people tended their crops and domestic animals, acts that tied them more closely with her and with the cycles of nature. Because of this, I think it is no accident that we refer to our planet as Mother Earth.

However, the Goddess was more than a mother deity of fertility who gave birth to creatures and fostered plant life. She was the cosmic creatrix who manifested everything, from the smallest thing on the earth to the vast heavens. The Goddess brought everything into existence and taught skills and crafts.

The Goddess as Waterbird

The Bird Goddess created, nourished, and charged the earth and its creatures with energy through the power of the life-giving element of water. She was regarded as the source of water that fell from the heavens, flowed on the surface of the earth, and welled up from underneath the ground. At home in the sky or in a river, waterbirds were considered the life of the waters. Waterbirds were an important source of food, and the annual migration was a major event. The return of ducks and geese to northern waters in the spring was an event for celebration because it ensured survival. Waterbirds brought abundance as food and as comfort through the use of their feathers. Cranes and other waterbirds also represented nourishment and abundance.

Millennia later the Egyptians and Babylonians regarded water as the source of life-giving forces as they witnessed fertile, new land being created from river silt, which would bring abundance. As the mother goddess of Egypt, Isis was associated with the annual flooding of the Nile. Like many rivers and marshy areas, the Nile is teeming with waterbirds.

Greek, Roman, Celtic, and Baltic legends linked goddesses to the magical potency of water in the form of streams, rivers, and sacred wells. In Ireland, the Boyne and Shannon Rivers were named after the goddesses Boann and Sinann, and the River Seine in France for Sequana. Sequana had a waterbird as her emblem and was often depicted in a duck-shaped boat. In addition, the name of the Gaulish goddess Nantosuelta means “winding river” and her pre-Celtic origins date back to Old Europe.21 In one depiction of her, Nantosuelta was shown with wings.

Born from water, Aphrodite has been portrayed sitting on a swan throne, standing on the back of a flying goose, and with doves. Her mythology has been traced back to Cyprus and even earlier to Mesopotamia. Although Artemis/Diana came to be regarded as a goddess of the hunt, she inherited the role of Mistress of the Animals. As such, swans and other waterbirds were closely associated with her.

While the character Mother Goose is but a small remnant of the mother-provider, the stork is still a symbol of the bringer of life. In mythology, not only did storks bring babies, they helped birth the new year and were considered the bringers of spring on their return to Europe. Like other migratory birds, their arrivals and departures were markers of cyclic time.

Although the mother/life-giving aspect of the Goddess is mainly associated with waterfowl, and odd as it may seem to us today, the vulture had a place here, too. With her name coming from the same root as the Egyptian word for mother, Mut was the archetypal mother goddess of Egypt and her symbol was a vulture. Worshipped with her husband Amun at Thebes, called Waset by Egyptians, Mut was regarded as the mother of the pharaohs. In addition, Isis was occasionally depicted as a vulture.

Nests: The Bird Goddess as Weaver and Giver of Crafts

It has been suggested that making baskets was an idea gleaned from birds, especially as it was an obvious way to carry off more eggs than could be held only in the hands. As cultures evolved from hunting and gathering and people became settled, depictions of the Bird Goddess changed, too. She became a spinner and a weaver, and the giver of crafts. Neolithic temples were not grand structures, instead they were house-like with connecting workshops that integrated daily craft activities with spiritual practice.

Weaving became a metaphor for creating life, perhaps because the Bird Goddess was portrayed as a spinner and a weaver who spun and wove the threads of life. Regarded as magical practices, spinning and weaving are methods for creating something from practically nothing. Simple threads become clothing and twigs become baskets.

As the giver of crafts, which included spinning, weaving, cloth dyeing, metallurgy, pottery, and music, Bird Goddess symbols were incised on spindle whorls, loom weights, crucibles, and musical instruments. Spindle whorls and loom weights are small, round or oblong discs that steady the movement of a spindle or prevent the threads on a loom from getting tangled. Inscriptions on these objects are thought to be dedications to the Goddess.

The practice of using Goddess symbols on spindle whorls and on figurines of people spinning continued into the classical period of Greece. However, in Greek mythology Athena was the giver of the crafts of pottery, spinning, and weaving. Her Roman counterpart, Minerva, was also associated with spinning and weaving. In addition, Norse goddess Freya was a spinner and a weaver, too, and she was often described as wearing a feather headdress.

Eggs: The Bird Goddess as Creatrix

To most of us, an egg is just a simple everyday item of food. However, throughout cultures worldwide and through time, the egg has had strong symbolic meanings. It represented new life and nourishment. The ability to hold life within was part of the mystery of the egg, as was the fact that it is fragile yet strong. Metaphorically, the egg is very grounding, providing balance to wings that liberate from the bonds of Earth.

With egg-shaped thighs, buttocks, and breasts, the Lespugue goddess and other similar figurines present a trinity of woman, bird, and egg. In addition to figurines, bird- and egg-shaped vessels and vases have been found in numerous places. Some of these depicted birds carrying eggs within their bodies.

In countless mythologies from later civilizations, a cosmic egg was the womb of the world and the source of all that existed. In some myths, a creator spirit took the form of an egg floating in primordial waters. According to Egyptian myth, the world egg was laid by a great goose. The Greeks believed the primordial egg was laid by a large black-winged bird. In many creation stories, the egg cracking open was equated with the breaking of the water, which was a sign of imminent birth. When this happened, the world and cosmos came into being and time began. The cosmic egg gave birth to the sun as symbolized by the yellow yolk. It also divided the sky and land as symbolized by the shell broken in half.

Life-Giving and Nurturing Symbols

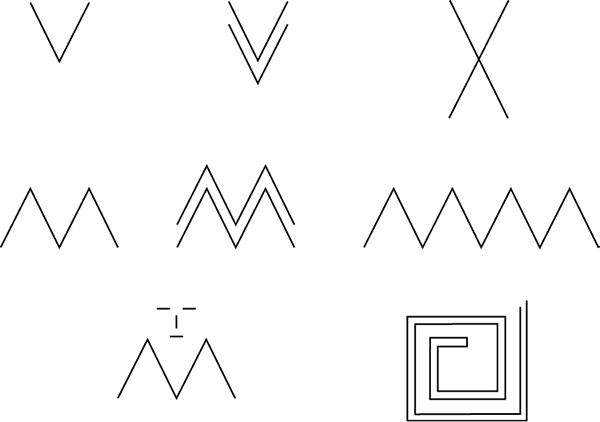

Migrating ducks, geese, and swans are well known for flying in the classic V-shape formation. It was a natural suggestion for the V to become associated with the Goddess as a symbol of fertility and abundance. The V and chevron (two or more Vs nested in each other) were the insignia of the Bird Goddess. Actually, the use of the V and chevron dates back to the Paleolithic period.

Found in a cave in Spain and dating to around 13,000—10,000 BCE, the shape of a crane or heron was engraved on bones that were also marked with chevrons.22 Use of the chevron continued throughout the Neolithic period and into later cultures. Resembling the markings of many birds, the V and chevron were used to represent a bird’s or woman/bird’s beak, wings, or feathers as well as to mark the pubic area. In addition to figurines, the V and chevron were used on vases, votive vessels, lamps, altars, plaques, and ritual objects.

Chevrons were commonly used to mark musical instruments. Bird-bone flutes marked with chevrons were found in France and other locations. In addition, a cache of flutes and rattles engraved with rows of chevrons was found in the Ukraine. Although the combination of birds and chevrons lingered into the eighth century BCE as a common Greek motif, their use lacked the sacredness they once held.

The cross-band or X, which can be considered as two juxtaposed Vs, is another important symbol of the Bird Goddess. The V, chevron, and X appeared on their own as well as in combination. According to Gimbutas, a chevron or X alone seemed to have marked an object as belonging to the Goddess, and the V, chevron, and X in combination served as a blessing or invocation. Chevrons placed sideways between the arms of Xs were a common configuration of these symbols.

Figure 1.2: The life-giving symbols of V, chevron, and cross-band (top row); M, double M, and zigzag (middle row); Goddess face and meander (bottom row)

The meander is another fundamental symbol of the Bird Goddess. Looking like a squared spiral, the meander is a rhythmic pattern that was often used in association with the V and the chevron. It was sometimes emphasized by being framed like a cartouche. According to Anne Baring’s interpretation, the meander was a symbol of water running beneath the earth and through caves, giving access to the otherworld.23 Like the spiral, it is thought to have represented a path between the worlds of the seen and unseen. The meander, like water from underground springs, represented the waters of birth bursting forth.

The meander was commonly used on beaked or winged figurines, altar pieces, and temple models. In later times, abbreviated meanders laid out in a straight line became known as the Greek key, a design that was frequently used on pottery and in temples.

An M-shaped symbol was used with chevrons and zigzags on pottery, pendants, and loom weights. The M and double M (one above the other) served as a primary symbol on vases and marked them as sacred objects. The M was positioned below the breasts on Goddess figurines to emphasize life-sustaining milk. The M symbol was also placed above birdlike faces, and frequently a double M was positioned underneath a face on large vases. The double M marked a face as that of the Goddess to imply that the vessel and its contents were sacred. While the Egyptians used an M-shaped hieroglyph (mu) to signify water, to the Phoenicians the same glyph meant running water.24 On Egyptian dishes, the mu hieroglyph often appeared with chevrons.

A row of connected Ms creates another symbol called the zigzag. Alternatively, it could be said that the M is an abbreviated zigzag. Throughout the world, the zigzag has been used to represent water. As early as 30,000 BCE, the M and zigzag were used to mark birdlike figures.25

Bird-shaped pottery was some of the earliest made during the Neolithic period and continued through the Bronze Age. Marked with the Goddess’s symbols, these vessels integrated sacred and mundane functions, as implements that served an ordinary purpose were used to pour sacred offerings. A vessel holding water or milk served as a representation of the Goddess, allowing her nourishment and blessings to be symbolically poured. A variation of the waterbird vessel with a spout shaped like a bird’s head and beak was found in northern Greece. On Crete, a Minoan pitcher in the shape of a waterbird with a long neck also had human breasts.

The overarching theme of these symbols and aspect of the Goddess encompasses creation/procreation, nurturing, and protection. In the next chapter, we will see how we can incorporate these symbols into our practices as we connect with this aspect of the Goddess and her birds.

21. Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition (London: Constable and Company, 1992), 313.

22. Gimbutas, The Language of the Goddess, 4.

23. Baring and Cashford, The Myth of the Goddess, 135.

24. Johnson, Lady of the Beasts, 36.

25. Gimbutas, The Language of the Goddess, 19.