Curanderismo Soul Retrieval: Ancient Shamanic Wisdom to Restore the Sacred Energy of the Soul - Erika Buenaflor M.A. J.D. 2019

The East for The Ancient Maya

The East: The Space of New Beginnings

![]()

Rebirth and New Life

For the Maya, the East was their primary direction and was identified as the place of the rising sun.19 The East was associated with strength and potency. On sixteenth-century maps it was frequently placed at the top. The East was the space from which the sun exited.20 Themes associated with the Eastern rising sun included flowers, Flower Mountain, solar imagery, quetzal feathers, plumed serpents, jade, and resurrection.21 The glyph for the sun and day is a cartouche that resembles a four-petaled flower. The petals reflect the sun rising, reaching its zenith, setting, and reaching its nadir.22 Both the sun god and maize god were believed to journey into the land of the dead, the Underworld, and resurrect from the dawning sun.23 Deceased rulers would have themselves dressed in the garb of the maize god in their tombs, alluding to their resurrection through the sun’s eastern ascent.24

Spatially, the Maya designed many of their city complexes on an east-west axis that tracked the daily path of the sun through the sky, and its west-east return through the Underworld at night. At Tikal, there were nine complexes that consisted of two pyramids facing each other on an east-west axis. They were flat-topped and had stairways on all four sides.25 Dzibilchaltún, an ancient Maya city in the Yucatán that was occupied for thousands of years, has an east-west assemblage at its main plaza; on the day of the spring and autumn equinoxes, sunlight illuminates the main eastern door of the Temple of the Seven Dolls. At this ceremonial axis, the elite would enact and embody their connection to daily and yearly solar cycles as well as to many other cycles of time, thereby establishing their legitimacy.26

The sun was believed to ascend from the East by steps or levels, often depicted as plumed-serpent stairs, going into the highest level of the Upperworld, and then descended from this peak, to finally trace a similar pattern in reverse in its journey through the Underworld.27 At the Postclassic site Tulúm, the Maya depicted the mythic event of emergence with a sun deity rising out of the eastern waters of the Caribbean Sea with gods and ancestors on the Flower Road of Flower Mountain.28 Structure 16 of Tulúm illustrates an extremely elaborate flower mountain scene, in which a pair of intertwined serpents carry gods on their backs as they rise out of a pool of water. These intertwined serpents are related to the path of the sun, especially to the idea that plumed serpents were floral roads and conduits for supernatural beings to Flower Mountain.29 The pool of water in the Structure 16 scene is not a cenote; instead it contains a marine blue ray, which Karl Taube posits is almost surely the Caribbean Sea, located less than 477 meters to the East of this structure. Structure 16 and the Castillo at Tulúm are not simply temples; they are symbolic Flower Mountains.30

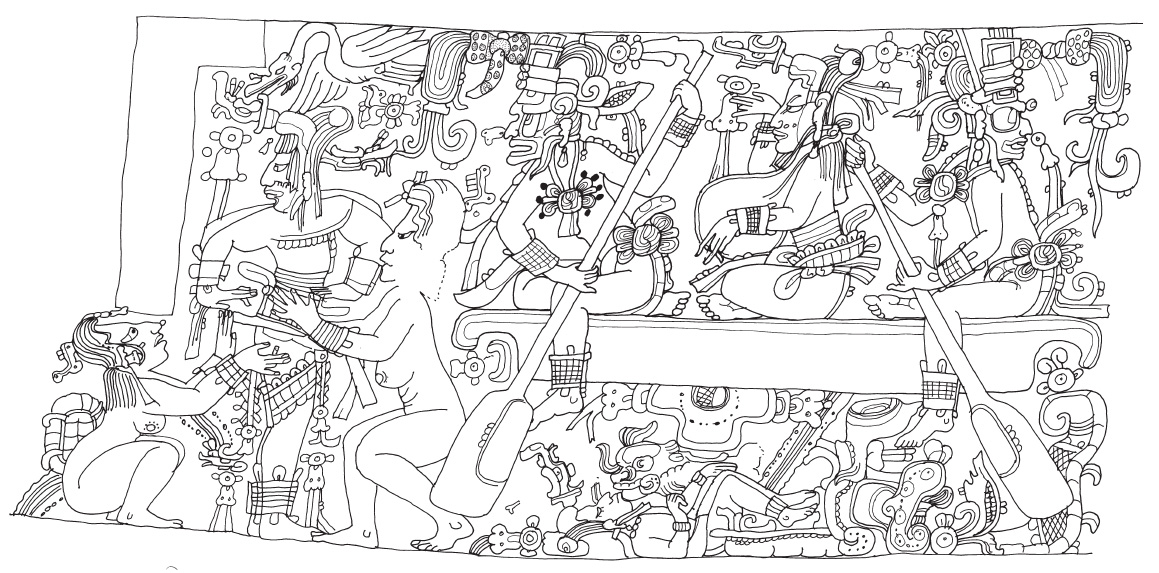

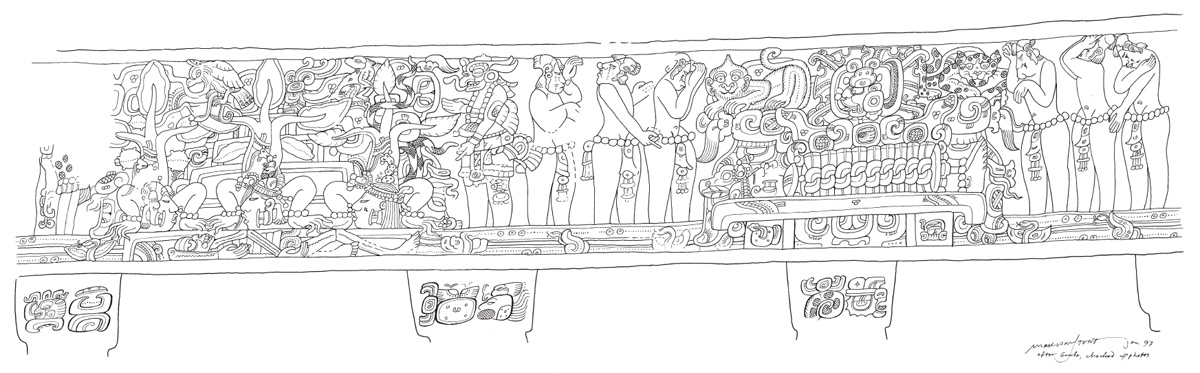

Classic Maya iconography often depicted the costuming of Maya rulers as that of the maize god, who embodied the principles of beauty, life, sacredness, and resurrection. Maya Vase 3033, for example, depicts the maize deity in the Underworld being dressed in jade adornments by maidens; once adorned, he is ready for his resurrection (see fig. 8.1,). Andrew Scherer points out that this scene apparently alludes to the dressing of the royal body for burial in preparation for a similar rebirth. The Berlin Vase illustrates a burial scene of a soul undergoing a solar ascent (see fig. 8.2,). The mourners are standing in the ocean, recalling the ascent of the sun from the eastern sea. The corpse is a bundled corpse of the maize deity. Rather than simply illustrating death, the scene shows resurrection with the new maize growth that spills over the deity’s bundled corpse.31

Royal ancestors, who portrayed the apotheosis of the solar or maize god, were also closely identified with Flower Mountain upon their death.32 The structure that covered Burial 48 of Tikal was ornamented with stucco masks of Flower Mountain deities with massive flowers on their brows and floating jewels and flowers on the walls. The eastern wall of Tomb 1 of Classic-period Rio Azul shows a Flower Mountain deity with a series of flowers on its brow. The other side of the east wall has the head of the sun deity atop the crocodile earth. The depiction of both Flower Mountain and the sun deity on the east wall alludes to the journey of the tomb’s occupant to Flower Mountain.33

Fig. 8.1. Rollout drawing of Vase 3033 showing Maize deity being transported by Paddler Deities in their canoe. On the other side of the vessel, two nude women dress the Maize deity.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA. SD-5515. Maya.

Drawing by Linda Schele. Copyright © David Schele.

The Year Bearer of the East for the Postclassic Yucatec Maya was kan (corn). These were generally lucky years, free of calamities.34 The East also presided over the five following tzolk’in day signs: imix, chicchan, muluc, ben, and caban. Imix symbolized the earth, and by extension abundance. In codices, imix was often compounded with a kan sign, signifying offerings and/or abundance of food and drink.35 Chicchan were an important group of deities who took the form of giant snakes or half-human, half-feathered serpents that brought the rains.36 The symbolic forms of muluc have been identified as the signs for jade. Jade was associated with water and the breath soul, suggesting that muluc was associated with life-giving water.37 Ben was related to the growing maize—green corn.38 Caban was the day of the young goddess of the earth, moon, and maize.39 Overall, East Year Bearer and day signs were fortunate, associated with fertility, earth, rain, and abundance.

Fig. 8.2. A burial scene embodying rebirth. Rollout drawing by Nikolai Grube of vessel K6547. On one side of the vessel (shown at right) a dead man, wrapped in a burial bundle, lies on a bench in his grave while mourners, dressed as the Maize deity, lament his death. On the other side (shown at left) the dead man, now reduced to bones, has been reborn as a cacao tree sprouting from the grave.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA. SD-5503. Maya. Drawing by Linda Schele. Copyright © David Schele.