Curanderismo Soul Retrieval: Ancient Shamanic Wisdom to Restore the Sacred Energy of the Soul - Erika Buenaflor M.A. J.D. 2019

The West for The Maya

The West: The Space of Death and Releasing

![]()

Danger, Courage, and Releasing

The Maya identified the West as the direction of the setting sun and the direction of the Underworld. Its color was black, and the symbol for black has been found on glyphs connected with the denizens of the Underworld.21 The glyph for the West, both on monuments and in the codices, was a hand over the winged k’in (sun or day) sign, probably to be read as the completion of sun or daylight. Another glyph for West seems to represent the sun with death markings. Here the hand takes on the form of an upright clenched fist.22

The West was the space where the sun deity, Kinich Ahau, was believed to shape-shift into a jaguar and where, at the same time, the aspect of the sun deity that did not become a jaguar was carried by a centipede through the Underworld. The centipede eventually disgorged the sun at dawn in the East.23 As a jaguar, Kinich Ahau passed to the Underworld to become one of the lords of night and would roam the Underworld.24 Kinich Ahau would emerge from the Underworld as dawn with death markings. To depict him during this journey, his attributes included a jaguar and the color black.25

For the Postclassic Yucatec Maya, the Year Bearer of the West was Ix, which was associated with calamitous years of drought, bad years for bread but good ones for cotton. Itzamná was the patron deity of these years. The New Year ceremonies for Ix were critical for preventing years whose instability would bring a loss of strength to the general populace, fainting, ailments of the eyes, a shortage of water, rampages of locusts, and the deaths of chiefs.26

The tzolk’in day signs of the West were largely associated with the night and the Underworld. They were akbal, manik, chuen, men, and cauac. The akbal glyph, the head of a centipede, is a prefix to the moon glyph when used as part of the name of Itzamná, and on two other occasions it forms the headdresses of two death deities. It has a similar association with Zotz, the leaf-nosed bat deity of the Underworld, and Oc, the dog, whose duty it is to lead the dead to the Underworld.27 The glyph for men represents the number 20 in the codices, a moon symbol, and an old moon goddess associated with danger and transition.28 Cauac is associated with storm, thunder, and rain. It was the day of the celestial dragons that sent the rain and storms.29 The associations and auguries of manik are the helping hand, whistler, and deer; it was likely the day of a god of hunting.30 Chuen was associated with arts and crafts and was the day of the god of arts and crafts.31

In the Postclassic codices, the Underworld deities God L and Yum Cimih or Kisin (meaning “lord of death” in Yucatec Mayan) were often associated with the West. Yum Cimih was the primary lord of the Underworld and in both form and symbolic domain was very similar to the Mexica Mictlantecuhtli. Although Yum Cimih was associated with death, decay, and disease, his energies were also complemented with rebirth and life as a cyclical natural procession.32

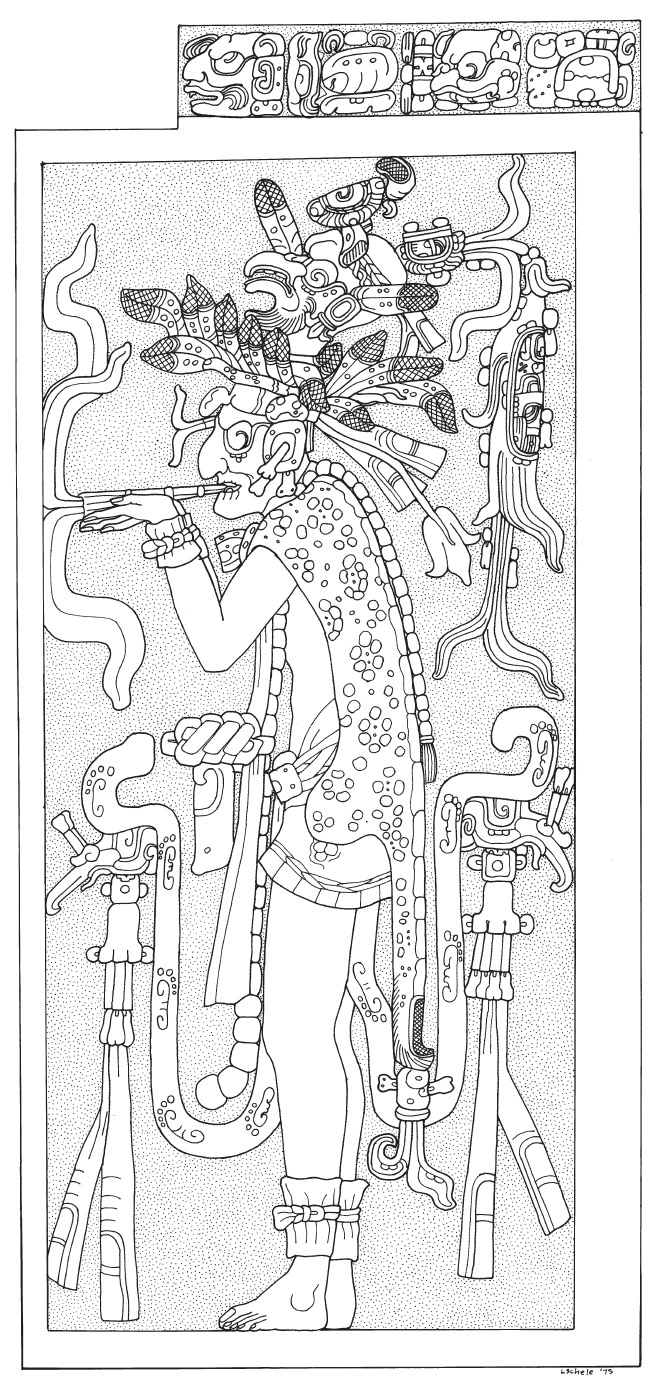

God L was a wealthy god of trade, tribute, and tobacco and would rise from the Underworld as a personification of Venus (see fig. 6.1).33 Although God L has been traditionally associated with the Underworld, he was able to exit his Underworld cave to commingle in the Middleworld and the first levels of the Upperworld.34 As Venus, God L was never able to rise beyond the first few celestial levels; he would come briefly into view above the earthly plane, only to return to his Underworld abode.35 He seems to have had considerable access to the Middleworld and was especially present in the upper subterranean layers, where water flows and sustains life.36 Despite his wealth, stature, and access to all three worlds, God L was ultimately taught the critical lesson of humility, as is depicted in Classic Maya vases.

As displayed in the Late Classic Princeton Vase K511, God L resides in a luxurious palace, seated on a jaguar pelt throne under curtains, and is wearing the richest of brocaded capes with an extravagant feather-trimmed hat, with his messenger and avatar, Thirteen Sky Owl, sitting on top. On the Vase of the Seven Gods, he is being revered by other Underworld denizens at the dawn of the world that began in 3114 BCE and was to end in 2012 CE. There are clues that he may have had a hand in pouring out the black resinous rain that destroyed the previous human race. The Princeton Vase depicts the beginning of his downfall. He is distracted by the beautiful women who attend to him while the Hero Twins behead one of his fellow Underworld gods (see plate 5).37

Fig. 6.1. God L, identified by his muan-bird headdress and jaguar-pelt cloak, smokes a large cigar. East sanctuary jamb from the temple of the cross, Palenque.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA. SD-176. Maya.

Drawing by Linda Schele. Copyright © David Schele.

On another late Classic vase, K5359, the Hero Twins have stripped God L of his fine clothes and flung them into the air, beginning his humiliation and defeat. The moon goddess and her rabbit companion are watching from above.38

On the Rabbit Vase, K1398, God L is on his knees submitting to the authority of the sun deity and petitioning for his aid (see plate 6). The Rabbit Vase refers to a mythical place in the north, which is supposedly where the Rabbit went after stealing God L’s clothes. The sun deity, who is typically denoted with crossed eyes and k’in signs,*15 wears a long-nosed chapat on his head to mark the nighttime staging of this scene. The events take place in the Underworld, presumably along the west-to-east course of the sun’s nocturnal passage.39 Unbeknownst to God L, the sun deity is working with the trickster Rabbit, who is hiding behind the sun deity and has God L’s fine clothes and accoutrements. On another vase, K5166, the Rabbit has taken God L’s clothes and accessories to the moon goddess, and God L is kneeling before her, asking for their return.40

The stories of the humiliation and defeat of both God L and the Lords of the Underworld in the Popol Vuh reveal the dangers of relying too much on wealth and stature to stay in power; they are illusory and can be easily stripped away. Although the deities of the Underworld were powerful because of their stature and wealth, the stories indicate that courage and persistence are more valued, as wealth can be taken, particularly when those who hold it are arrogant. Hence, when one moves through the tests of the Underworld, it is also necessary to release illusions of grandeur. Only then can there be rebirth and life.