Curanderismo Soul Retrieval: Ancient Shamanic Wisdom to Restore the Sacred Energy of the Soul - Erika Buenaflor M.A. J.D. 2019

The Ancient Maya South

The South: The Space of Discovery and Understanding

![]()

Tests, Trials, and Tribulations

The Maya associated the South with the color yellow and the right or left hand of the sun.24 As fixed spaces, the North and South were derivatively named as side quadrants to the primary east and west quadrants of the sun, as most Maya languages do not have terms for north and south.25 Some Maya languages refer to the South as the right hand of the sun or the left hand of the sun, on the basis of local geographical conditions.26It was also the space where the sun went into and through the Underworld—the space of trials and tribulations, and possible rebirth and regeneration.27 Rebirth and regeneration were attainable if one passed the tests here or perhaps emulated the actions of those that continuously triumphed over the forces of death, such as the sun and maize deities.28

The architectural layouts of many Maya cities of the Classic period associate the South with both the Underworld and the path into it. The artwork on the monuments indicates that the South was under the guardianship of the death god, the lord of the Underworld.29 The south side of the Great Plaza of Tikal, for example, contains references to the Underworld itself, as well as passages into and out of it. Bounding the south of the Great Plaza is Structure 5d-120, which is a single-room building with nine doorways, symbolizing the Underworld with its nine levels and lords of the night.30 The divider or passageway into the Underworld is the ball court. Ball courts served as boundary markers and points of integration, including the juxtaposition between the Middleworld and Underworld.31

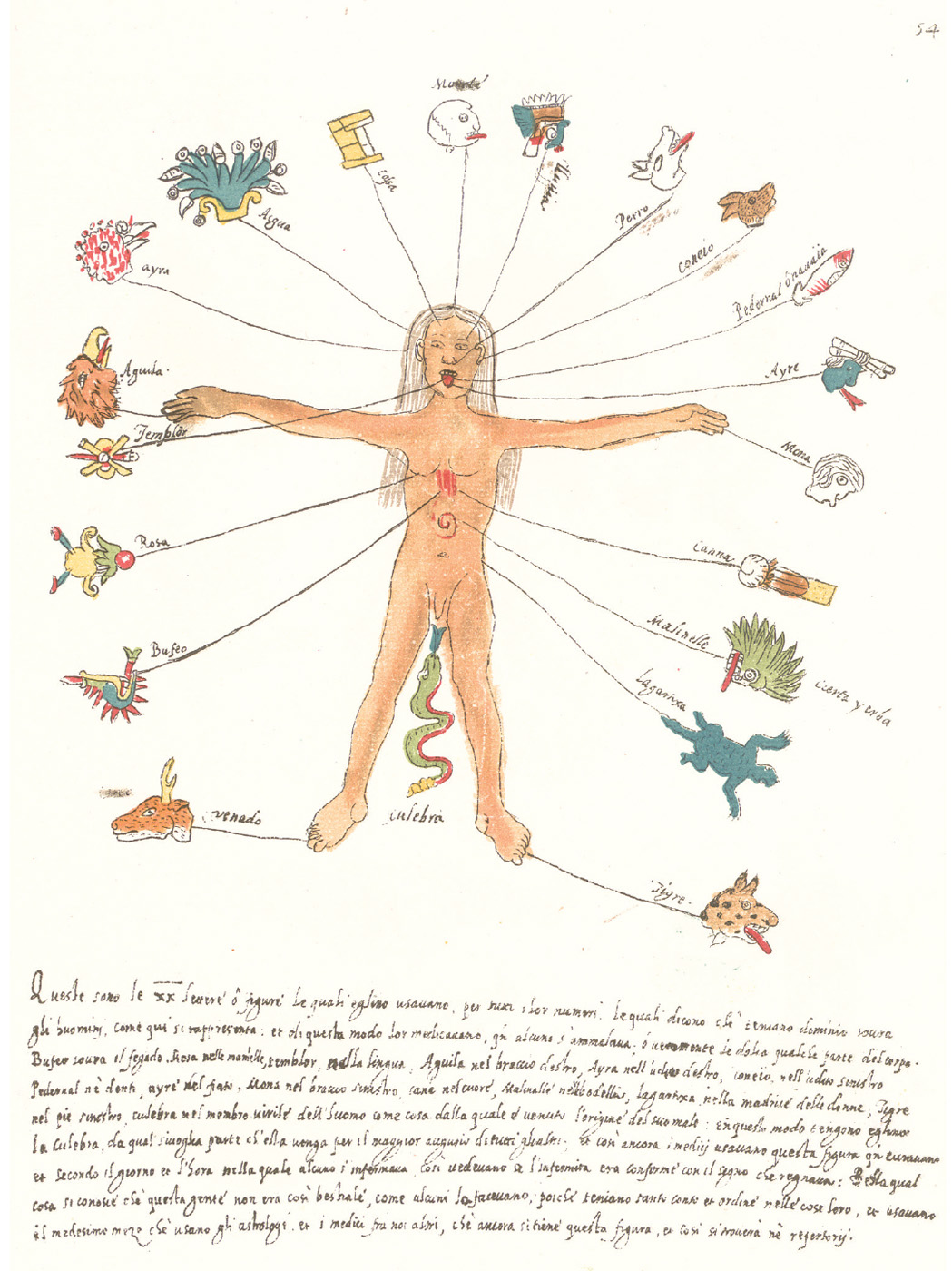

Plate 1. Tonalpohualli day signs associated with concentrations of tonalli within the body.

From Codex Vaticanus 3738 A, Loubat 1900 version, page 3v.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA.

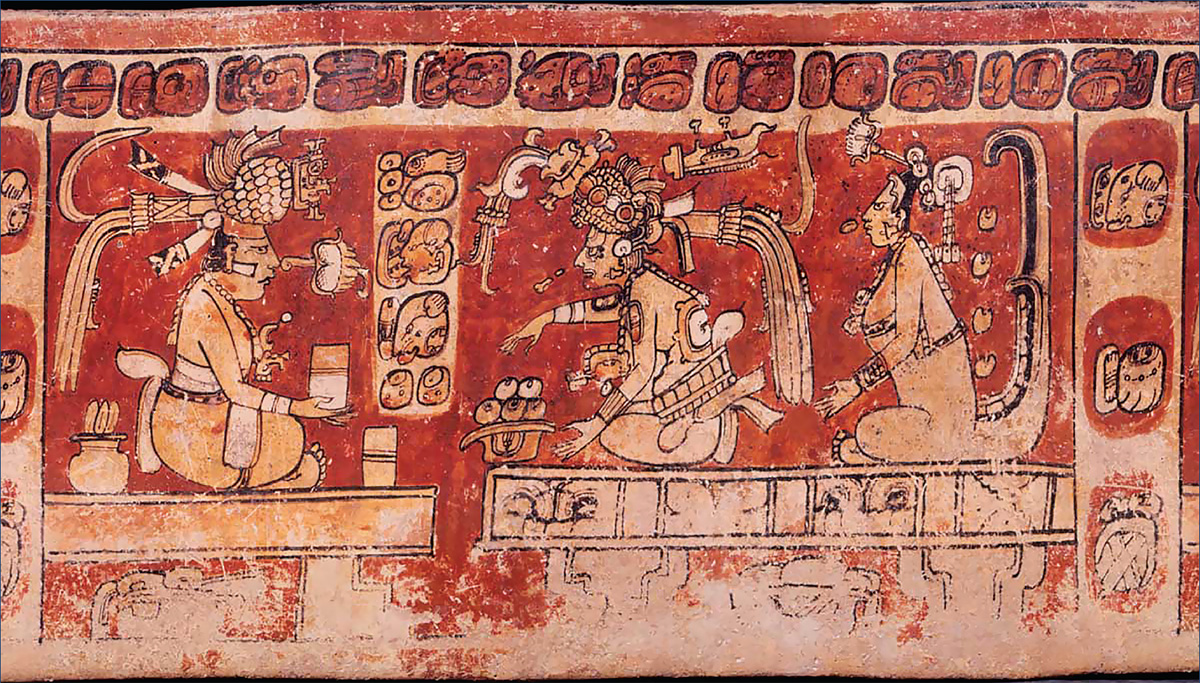

Plate 2. The creator deity Itzamná in the middle, inhaling breath as sacred essence energy. Note Itzamná’s earspool bead, identical to the breath sign before his face.

Vase K504. Photograph © Justin Kerr.

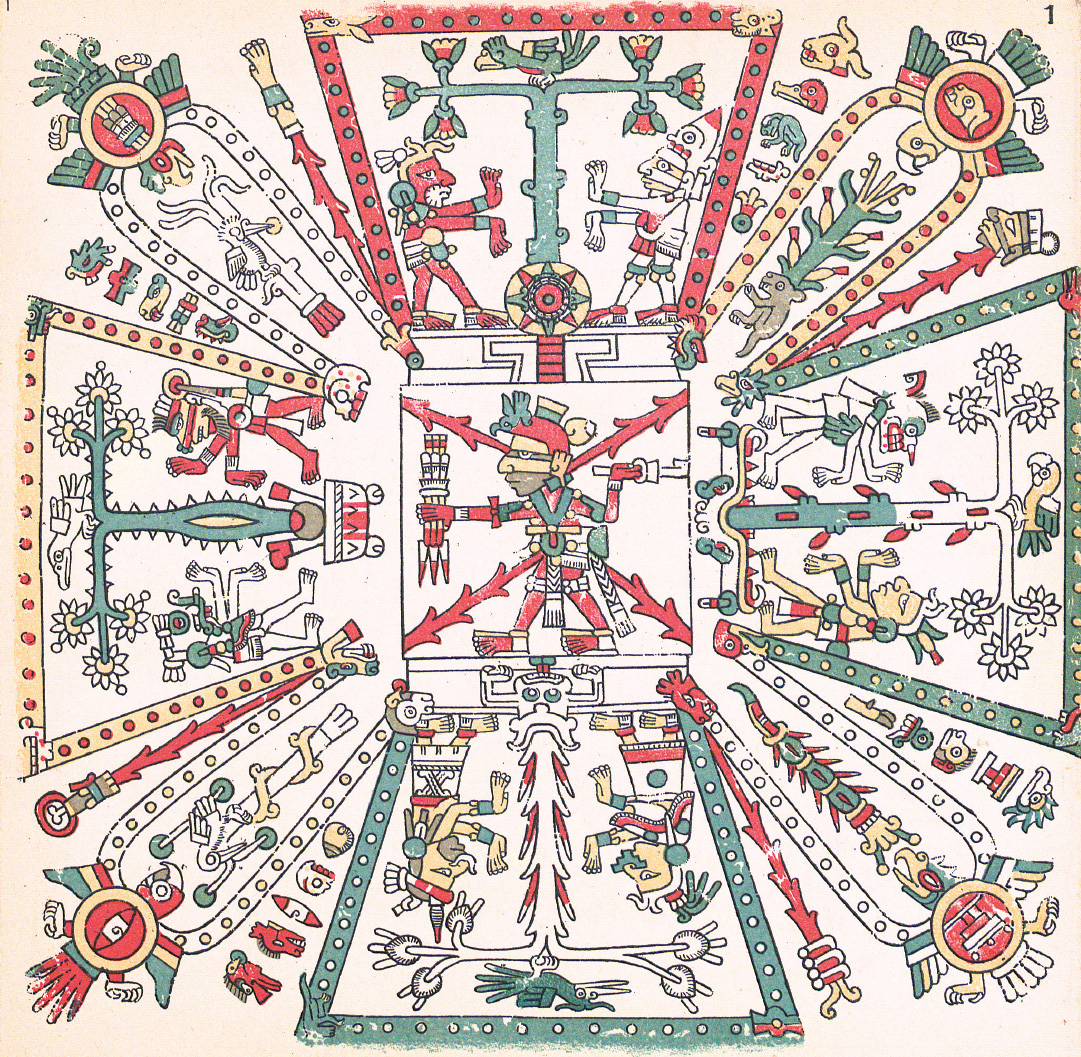

Plate 3. Cosmogram illustrating the four cardinal spaces and the center; presiding is the deity Xiuhtecuhtli (Nanahuatzin). The red frame at the top of the page represents the East, the left is North, the bottom is the West, and the right is the South.

From Codex Fejéváry-Mayer, Loubat 1900 version, page 1.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA.

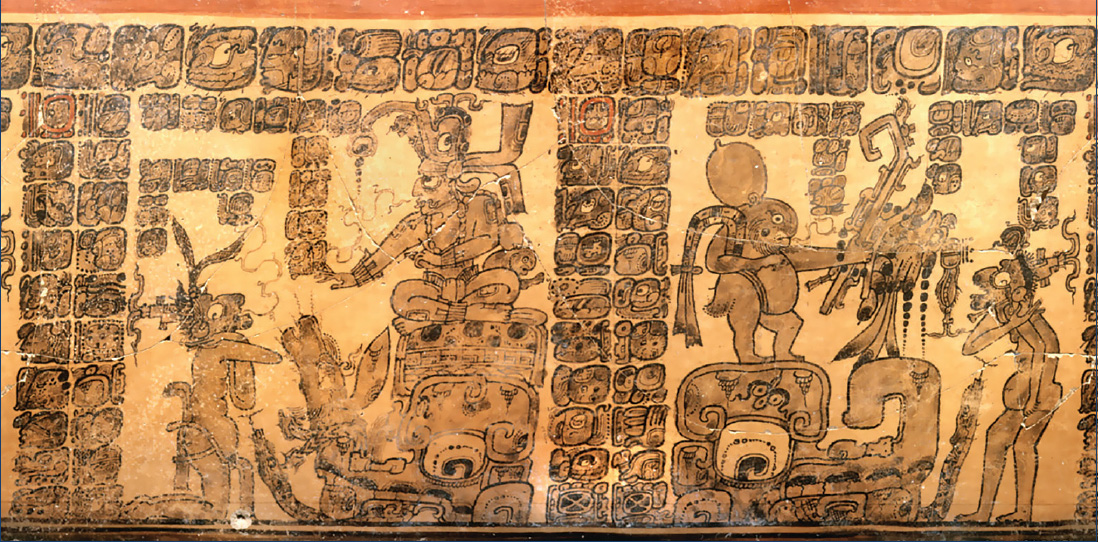

Plate 4. Scrying into a mirror and connecting with or becoming an animal coessence. The vase depicts a hybrid of a dog and jaguar contorting on the ground. This being and the insect on it are likely a way.

Vase K2929. Photograph © Justin Kerr.

Plate 5. God L resides in a luxurious palace, seated on a jaguar pelt throne under curtains, and is wearing the richest of brocaded capes with an extravagant feather-trimmed hat, with his messenger and avatar, Thirteen Sky Owl, sitting on top. This Princeton Vase depicts the beginning of his downfall. He is distracted by the beautiful women who attend to him while the Hero Twins behead one of his fellow Underworld gods.

Princeton Vase, K511. Photograph © Justin Kerr.

Plate 6. God L is on his knees submitting to the authority of the sun deity and petitioning for his aid.

Rabbit Vase, K1398. Photograph © Justin Kerr.

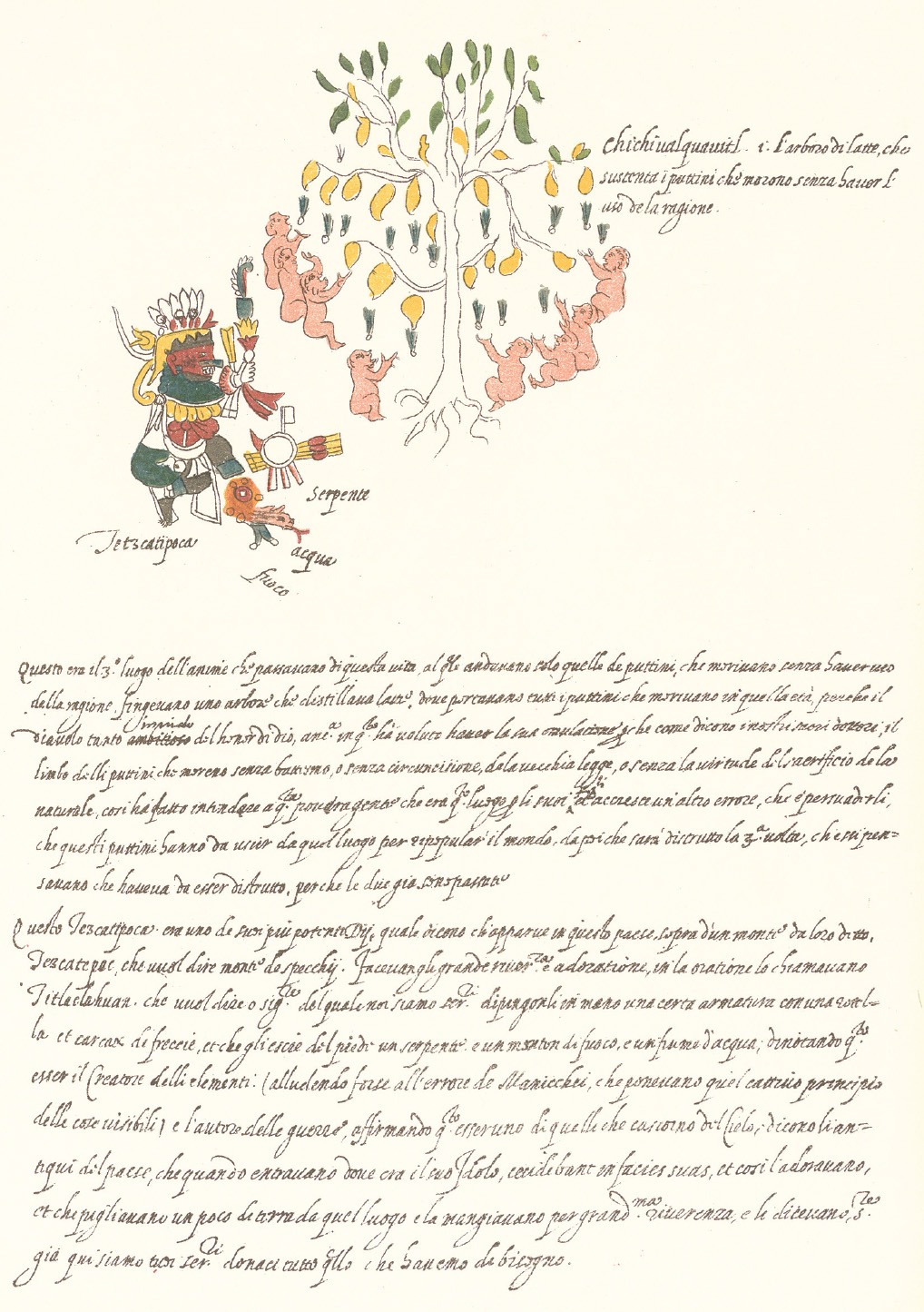

Plate 7. Chichihualcuauhco, place of the nursemaid tree, where the souls of dead children went.

From Codex Vaticanus 3738 A, Loubat 1900 version, page 54r.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA.

Plate 8. Flower Mountain images at Uxmal, a Classic-period site in the Yucatán.

Photograph by Erika Buenaflor.

Plate 9. Witz masks at the Classic-period site Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán.

Photograph by Erika Buenaflor.

In another Classic-period site, Copán, the cardinal spaces are occupied by imposing architectural groups, each approximately one kilometer from the ball court. The South is bounded by the acropolis, the Copán River, and a small complex with frog sculptures south of the river.32 As noted, the entrance into the Underworld was a watery space, and the Underworld itself was a watery place through which two rivers flowed.33

The South as the Underworld was a dreaded place of decay, disease, and trials and tribulations—each one of its nine levels was a test. But the Underworld also contained regenerative powers.34 Those that survived its trial and tribulations, such as the Hero Twins of the Popol Vuh, could depart with regenerative powers, become deified, ascend into paradisal realms, or become celestial bodies. Particularly after death, souls were at the peril of being trapped by the nefarious Underworld beings.

The Maya consequently emulated mythical heroes, such as the maize god and the sun god, who had triumphed over the forces of immorality, death, and the Underworld.35 In their mortuary rites, the Maya would enact the myths of the resurrection of the maize god and the sun god to ensure the ascent of their souls out of the Underworld and into ancestral mountains and other celestial paradises.36 Some of the tombs of deceased rulers from the Classic period depict their release from the Underworld and resurrection. Copán Stela II of Temple 18, found on an interior staircase to a burial chamber, depicts the city’s king Yax Pasah rising from the jaws of the Underworld to his moment of rebirth. Yax Pasah emerges from the Underworld as the maize deity, whose leafy curls surround the back of his head, and as K’awiil (lightning serpent deity), with a smoking tube on his forehead.37 Many ceramic vessels depict the youthful maize deity in the act of arising from the Underworld through a crack on a turtle’s back, the turtle representing the surface of the Earth floating in primordial waters.38

The sarcophagus lid of ruler K’inich Janaab’ Pakal I in Classic-period Palenque depicts his departure out of the Underworld and his resurrection, regeneration, and rebirth. The Underworld is depicted by the open maw of an infernal centipede. The resurrected ruler rises up along a World Tree, which acts as an axis mundi or portal that transfers his body to a flowery realm in the Upperworld.39 Pakal wears the symbols of the sun god, and like the sun, he will be reborn at dawn. He also wears the skirt of the maize god, who is known to die annually and resurrect. The nine lords of the Underworld, which he is resurrecting from, are depicted in stucco reliefs on the walls of his tomb. In the space between his tomb and the temple above, there are thirteen vaults, representing the thirteen levels of the Upperworld he is ascending into.40

The Year Bearer of the South for the Postclassic Yucatec Maya was Cauac, who influenced the luck of thirteen years.*13 The Cauac years were generally unfortunate: they were believed to be ruled by the god of death; during them, many would die. Causes would include hot spells, lack of rain, and plagues of birds and ants that would destroy crops. But the misfortune could always be counterweighed with diligent offerings and ceremonies to alleviate the potential distress.41 The character of the numerical coefficient (1 through 13), of the Cauac years, and the tzolk’ in day sign, could also temper the generally unfortunate character of these years.42

The South also presided over the five following tzolk’in day signs from their divinatory calendar: eb, cib, ahau, kan, and lamat. The day signs for the Maya were actual deities in their own right.43 Eb combined the symbols for death and water, possibly signaling the ruin of vegetation by mildew. The Dresden Codex depicts Deity O, an aged moon goddess, with an eb sign coming out of her jar of gushing water, which may depict the destruction of a previous world by deluge.44 The personified form of cib resembled a jaguar god, a deity of the Underworld and darkness.45 Ahau means “lord” in various different Maya languages; it was the day of the sun deity.46 Kan in Yucatec Mayan means “corn,” yellow, and by extension, ripe. The kan day sign represented grains of maize and growth.47 Finally, the glyph for lamat was the sign for the planet Venus. In head variants,*14 Venus signs were often depicted on a celestial dragon. Lamat was the day of the Venus god and had a celestial nature as a bright star.48 The tzolk’in day signs presided over by the South had associations with death, the Underworld, the sun, growth, and celestial bodies, which could be fortunate or dangerous. Regardless of their character, the people were still expected to be disciplined and engage in rites to honor these signs so that good, or at any rate better, fortune could ensue.