Curanderismo Soul Retrieval: Ancient Shamanic Wisdom to Restore the Sacred Energy of the Soul - Erika Buenaflor M.A. J.D. 2019

The Ancient Maya Center

Our Sacred Center and Trance-Journeying: A Portal to Other Worlds

![]()

A Portal in the Cardinal Spaces

For the Maya too, the center was the space of creation energy. It sustained life and served as a portal into the cardinal spaces and the nonordinary realms. The center was often depicted as the three-stone hearth, a great ceiba tree, or a ruler who could act as an intermediary between nonordinary realms. Sacred objects, such as hearths, censers, and offering bowls, could act as the central axis and serve as gateways to the other realms, as well as house their conjured supernatural beings.16 Numerous Classic Maya scenes depict a tree rising out of a censer that is serving as the axis mundi, along with a rain of flowers and jewels around the censer and tree, which denote contact with the spirit realms.17

The central axis of the universe was often portrayed as a World Tree with a celestial bird called Itzam-Ye perched on the top of the branches (see fig. 2.1). The World Tree acted as a cosmic bridge for the nonordinary realms; its roots were deep in the Underworld, its trunk was in the Middleworld, and its branches reached the Upperworld.18 The World Tree, as the central axis, was mirrored at each of the other cardinal spaces—South, West, North, and East—each with its own distinct tree and bird. These other World Trees, seen as the four corners of the sky, could also act as bridges between worlds.19

A common creation image for the Classic Maya was that of “three stone settings.” Stela*7 C of Late Classic Quiriguá depicts this creation story. The beings who set the stone and their names are identified as follows:

The Jaguar Paddler and the Stingray Paddler seated a stone.

It happened at No-Ho-Chan, the Jaguar-throne-stone.

The Black-House-Red God seated a stone.

It happened at the Earth Partition, the Snake-throne-stone.

Itzamna set the stone at the Waterlily-throne-stone.20

The setting of the three stones defined and manifested a center for the cosmos and allowed the sky to be lifted from the primordial sea.21 The three stones of creation are symbolic prototypes for the three-stone hearths of the Maya, which, like those of the Mexica, were located at the center of the home and were used to cook food.22

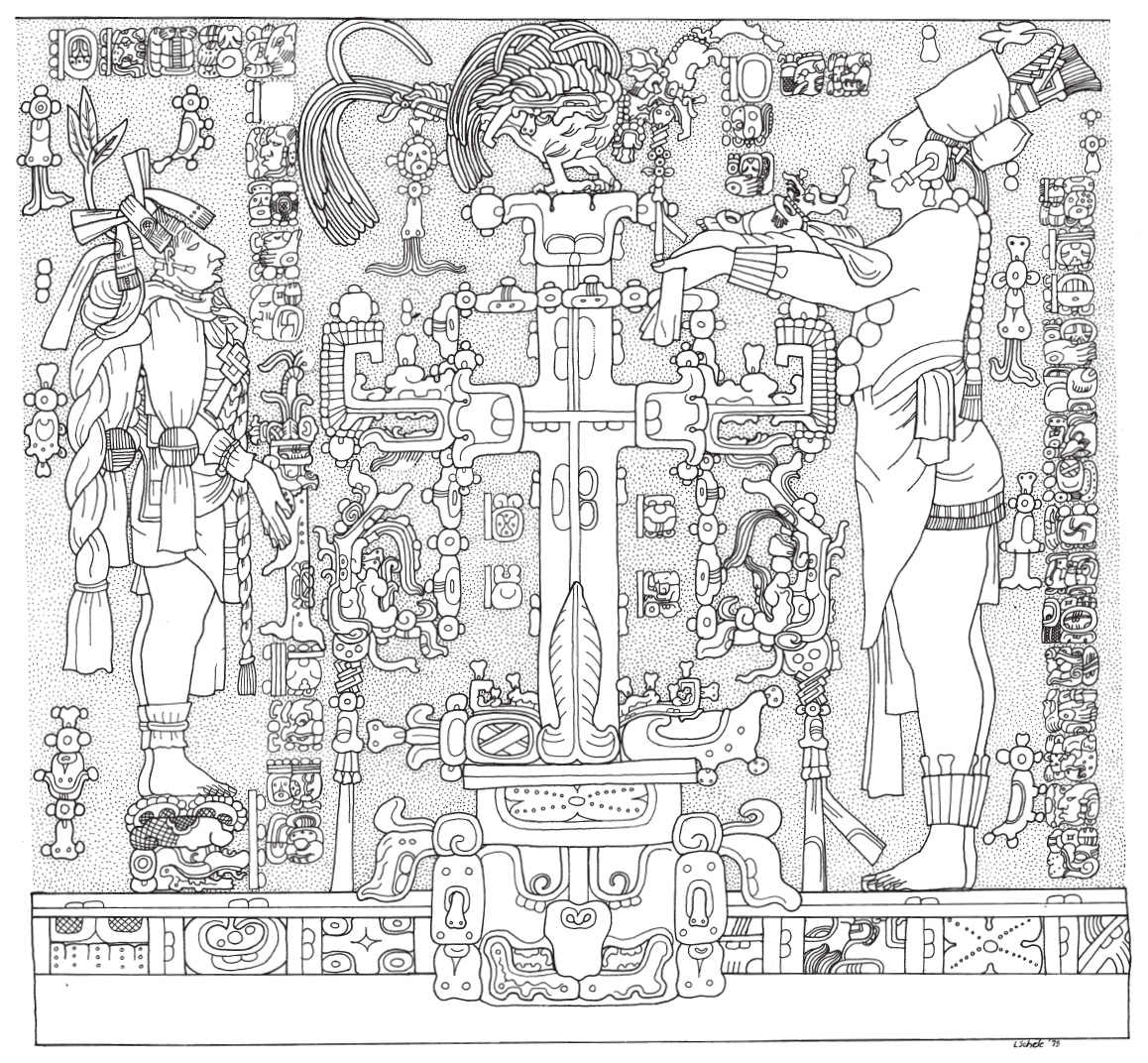

Fig. 2.1. The central axis of the universe was often portrayed as a World Tree. Two individuals stand on a skyband. At the left, K’inich Kan B’alam II, king of Palenque, named by the accession text directly in front of him, holds a small Quadripartite Badge of rulership, possibly connecting the cardinal spaces with his rulership. The larger individual, right, holds a K’awiil figurine, the serpent lightning deity. At center, between them, a World Tree rises from a Quadripartite Badge. The Celestial Bird, Itzam-Ye, is perched atop the World Tree, while a double-headed serpent curls through the arms of the tree.

The panel is from the Temple of the Cross at Palenque.

Courtesy of Ancient Americas at LACMA. SD-170. Maya. Drawing by Linda Schele.

Copyright © David Schele.

Maya homes were sacred spaces, small-scale replicas of the cosmos. The four poles that framed the corners of the house corresponded to the four World Trees and four corners of the sky, and its central pole and hearth served as the axis mundi, the heart of the home.23 Modern ethnographic accounts of the Maya also indicate that sacred spaces, such as mountains and homes, act as a central axis, with a heart that can link the nonordinary realms together. The “heart of the mountain” is said to contain the home of the Earth Lord.24

The Maya ruler was also often represented as a conduit between the realms of the cosmos.25 The art of the lower and upper temples of the jaguars at Late Classic Chichén Itzá, for example, depicts the rulers in a shamanic transformed state in both the Middleworld and Upperworld.*8 26 A series of stelae at the central plaza of Classic-period Copán portray their thirteenth ruler, Waxaklahun Ub’ah K’awil, commonly referred to as 18 Rabbit, acting as a central axis. The seven stelae were in the heart of their city and were positioned at the cardinal and intercardinal points of the plaza. Stela C, like the other six, depicts 18 Rabbit at the center of the universe. On both faces of Stela C, 18 Rabbit grasps double-headed serpent bars representative of the celestial sky or Upperworld. From the serpents’ maws, ancestors come out from the outer limits of the stela. The lower portion of the east side of Stela C has him in the form of a crocodile tree emerging from a mountain. His loin apron becomes the trunk of the World Tree, while serpents, often associated with the sky, extend out both sides, forming his branches. The costume worn by him on the west side of Stela C relays him as the World Tree that supports the cosmos and sustains creation.27