White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (2016)

Part II

DEGENERATION OF THE AMERICAN BREED

CHAPTER SEVEN

Cowards, Poltroons, and Mudsills

Civil War as Class Warfare

You have shown yourselves in no respect to be the degenerate sons of our fathers… . It is true you have a cause which binds you together more firmly than your fathers. They fought to be free from the usurpations of the British Crown, but they fought against a manly foe. You fight against the offscourings of the earth.

—President Jefferson Davis, January 1863

In February 1861, Jefferson Davis, the newly elected president of the Confederacy, traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, for his inauguration. Greeted by an excited crowd of men and women, he gave a brief speech outside the Exchange Hotel. Addressing his people as “Fellow Citizens and Brethren of the Confederate States of America,” he invoked a tried-and-true metaphor to describe his new constituency: “men of one flesh, one bone, one interest, one purpose, and of identity of domestic institutions.” As it happens, his was the same biblical allusion his vice president, Alexander Stephens of Georgia, had commandeered in Congress in 1845 when he rose in support of the annexation of Texas and its Anglo-Saxon population.1

The one-flesh marital trope had both a racial and a sexual dimension, presenting the desirable image of a distinct breed. Davis echoed the words of his namesake, Thomas Jefferson, when he described his new country as one that embodied “homogeneity.” In Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson had made native-born stock and shared cultural values the basis of national unity and security. The idea of an “American breed” was firmly entrenched.2

Expositors of the “American breed” model all gravitated to an “us versus them” calculus, which became useful as territorial expansion unfolded and cultures collided. As the South seceded, further distinctions needed to be made. So when the Confederate president recurred to one of his favorite couplets, “degenerate sons,” he appealed at the same time to the “days of ’76,” making sure his audience understood that the revolution of 1861 aimed to restore the virtuous pedigree of the founding fathers. The southern people, he assured the crowd, were heirs of the “sacred rights transmitted to us.” If required, they would display “Southern valor” on the field of battle. The new nation would prove to the world that “we are not the degenerate sons” of George Washington and his noble peers, but in fact the genuine offspring and rightful lineage of the first American republic.3

And then there was the flip side. Davis returned to the bully pulpit in the final days of 1862, addressing the Mississippi legislature, where he openly rebuked the men who comprised the Union forces. They were nothing more than “miscreants” deployed by a government that was “rotten to the core.” The war proved that North and South were two distinct breeds. Whereas southerners could lay claim to a positive pedigree, their enemy could not. Northerners were heirs to a “homeless race,” traceable to the social levelers of the English civil war. What’s more, the North’s unflattering genealogy began in the “bogs and fens” of Ireland and England, where they were spawned from vagabond stock and swamp people. It was a delusion, Davis declared, to imagine that these two races could ever be reunited. No loyal Confederate would ever wish to lower himself and rejoin his lessers.4

Returning to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Davis gave another such speech in early January 1863. “You have shown yourselves in no respect to be the degenerate sons of our fathers,” he repeated. Yet in one important respect, the South’s cause was radically new. Their Revolutionary forebears had fought against a “manly foe.” Confederates faced a different enemy: “You fight against the offscourings of the earth,” the president railed. Yankees were a degenerate race, worse than “hyenas.” In dehumanizing the Union troops, Davis placed them close in nature to a ravenous, cowardly species that hunted its innocent prey in whimpering packs.5

✵ ✵ ✵

Wars are battles of words, not just bullets. From 1861, the Confederacy had the task of demonizing its foe as debased, abnormal, and vile. Southerners had to make themselves feel viscerally superior, and to convince themselves that their very existence depended on the formation of a separate country, free of Yankees. Confederates had to shield themselves from the odious charge of treason by fighting to preserve a core American identity that nineteenth-century northerners had corrupted.6

To do so, the Confederacy had to create a revolutionary ideology that concealed the deep divisions that existed among its constituent states. Tensions between the cotton-producing Gulf states and the more economically diverse border states were genuine. We tend to forget that an estimated three hundred thousand white southerners, many from the border states, fought for the Union side, and that four border states never seceded. In Georgia, throughout the war, dissent from Davis’s policies was significant. Richmond was tasked with smoothing over the ever-widening division between slaveholders and nonslaveholders caused by conscription and food shortages. Claims to homogeneity were more imagined than real.7

The Confederacy built upon the South’s prewar critiques of Yankee attributes. The Yankee gentry was allegedly composed of upstarts who lacked southern refinement. Their “freedom” was really low-class fanaticism. As one Alabama editor transparently put it in 1856:

Free society! We sicken at the name. What is it but a conglomeration of greasy mechanics, filthy operatives, small-fisted farmers, and moon-struck theorists? All the northern, and especially the New England states, are devoid of society fitted for well-bred gentlemen. The prevailing class one meets with is that of mechanics struggling to be genteel, and small farmers who do their own drudgery, and yet are hardly fit for association with a southern gentleman’s body servant.8

At a parade in Boston in that year, supporters of the first Republican presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, embraced the “greasy mechanic” slur as a badge of honor by displaying it on one of their banners.9

All the lurid name-calling had a specific purpose. Turning the free-labor debate on its head, proslavery southerners contended that the greatest failing of the North was its dependence on a lower-class stratum of menial white workers. Ten years before he became president of the Confederacy, Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi had argued that the slave states enjoyed greater stability. Recognizing that “distinctions between classes have always existed, everywhere, and in every country,” he observed that two distinct labor systems coexisted in the United States. In the South, the line between classes was drawn on the basis of “color,” while in the North the boundary had been marked “by property, between the rich and poor.” He insisted that “no white man, in a slaveholding community, was the menial servant of anyone.” Like many other proslavery advocates, Davis was convinced that slavery had elevated poor whites by ensuring their superiority over blacks. He was wrong: in the antebellum period, class hierarchy was more extreme than it ever had been.10

James Henry Hammond, South Carolina’s leading proslavery intellectual, coined the term “mudsill” to describe the essential inferiority of the North’s socioeconomic system. It was “mudsill” democracy that the Confederacy would decry as it made its case against the North. By 1861, mudsill democracy had seeped into portrayals of the mudsill Union army—meant to be a foul collection of urban roughs, prairie dirt farmers, greasy mechanics, unwashed immigrants, and by 1862, with the enlistment of Afro-American Union troops, insolent free blacks. All in all, they were Davis’s waste people, the “offscourings of the earth.”11

In 1858, Hammond had publicly aired his ideas before the U.S. Senate in a speech that proved to be widely popular. Its most enduring critique concerned the fixed character of class identity. In all societies, “there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life.” With fewer skills and a “low order of intellect,” the laboring class formed the base of civilized nations. Every advanced society had to exploit its petty laborers; the working poor who wallowed in the mud allowed for a superior class to emerge on top. This recognized elite, the crème de la crème, was the true society and the source of all “civilization, progress, and refinement.” In Hammond’s mind, menial laborers were, almost literally, “mudsills,” stuck in the mud, or perhaps in a metaphoric quicksand, from which none would emerge.12

If all societies had their mudsills, then, Hammond went on to argue, the South had made the right choice in keeping Africa-descended slaves in this lowly station. As a different race, the darker-pigmented were naturally inferior and docile—or so he argued. The North had committed a worse offense: it had debased its own kind. The white mudsills of the North were “of your own race; you are brothers of one blood.” From Hammond’s perspective, their flawed labor system had corrupted democratic politics in the northern states. Discontented whites had been given the vote, and, “being the majority, they are the depositories of all your political power.” It was only a matter of time, he warned ominously, before the poor northern mudsills orchestrated a class revolution, destroying what was left of the Union.13

Jefferson Davis and James Hammond spoke the same language. Confederate ideology converted the Civil War into a class war. The South was fighting against degenerate mudsills and everything they stood for: class mixing, race mixing, and the redistribution of wealth. By the time of Abraham Lincoln’s election, secessionists claimed that “Black Republicans” had taken over the national government, promoting fears of racial degeneracy. But a larger danger still loomed. As one angry southern writer declared, the northern party should not be called “Black Republicans,” but “Red Republicans,” for their real agenda was not just the abolition of slavery, but inciting class revolution in the South.14

Confederate ideologues turned to the language of class and breeding for obvious reasons. They were invested in upholding a hierarchy rooted in the ownership of slaves. When in 1861, Jefferson Davis spoke of “domestic institutions,” he meant slavery, and its protection formed the central creed of the new constitution that bound “men of one flesh” to the new nation. Vice President Alexander Stephens, in a speech given in Savannah on his return from the constitutional convention, took pains to make Hammond’s mudsill theory the cornerstone of the Confederacy. The delegates had instituted a more perfect government: first, by ensuring that whites would never oppress classes of their own race; and second, by affirming that the African slaves “substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it.” Refuting the premise of Lincoln’s 1858 “House Divided” speech (that a nation cannot stand half slave, half free), Stephens equated the Confederacy with a well-constructed mansion, with slaves as its mudsill base and whites its “brick and marble” adornment. Presumably the brick represented the sturdy yeoman and the planter elite its finely polished alabaster.15

Class concerns never lost their potency during the war. In 1864, as defeat loomed and the South’s leaders contemplated augmenting the army with slaves, some feared that the rebel nation would fall if deprived of its lowest layer. Black men would achieve a rise in status through military service, undermining general assumptions about the color-coded social hierarchy. Slaves had been impressed by state governments to build fortifications as early as 1861—a policy later adopted by the Confederate high command and the Davis administration. But putting slaves in uniform was a far more radical move, because it elevated them (as Hammond and Stephens had argued) above their station as menial mudsills. Texas secessionist Louis T. Wigfall raged in the Confederate Senate that arming slaves was utterly unthinkable, no different than the British eradicating their landed aristocracy and putting “a market-house mob” in its place. (“Market-house mob” was another term for class revolution, and deposing the aristocracy would turn the Confederacy into another mudsill democracy—like the enfranchised rubbish of the North.) Sounding like a snobbish English lord, Wigfall added that he did not want to live in a country where “a man who blacked his boots and curried his horse was his equal.” In his mind, slaves were born servants, and raising them up by making them soldiers disrupted the entire class structure. Protecting that racial and class system was why southerners had seceded. In this way, class angst suffused Confederate thinking and served to unite southern elites.16

Class mattered for another reason. Confederate leaders knew they had to redirect the hostility of the South’s own underclass, the nonslaveholding poor whites, many of whom were in uniform. Charges of “rich man’s war and poor man’s fight” circulated throughout the war, but especially after the Confederate Congress passed the Conscription Act of 1862, instituting the draft for all men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five. Exemptions were available to educated elites, slaveholders, officeholders, and men employed in valuable trades—leaving poor farmers and hired laborers the major target of the draft. Next the draft was extended to the age of forty-five, and by 1864 all males from seventeen to fifty were subject to conscription.17

The Union army and Republican politicians advanced a strategy aimed at further exploiting class divisions between the planter elite and poor whites in the South. Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, as well as many Union officers, believed they were fighting a war against a slaveholding aristocracy, and that winning the war and ending slavery would liberate not only slaves but also poor white trash. In his memoir, Grant voiced the class critique of the Union command. There would never have been secession, he wrote, if demagogues had not swayed nonslaveholding voters and naïve young soldiers to believe that the North was filled with “cowards, poltroons, and negro-worshippers.” Convinced that “one Southern man was equal to five Northern men,” Confederate soldiers saw themselves as a superior people. (The same five-to-one ratio was used by North Carolinian Hinton Rowan Helper when he defended the Anglo-Saxon race in Land of Gold and claimed that one Kentuckian could trounce five dwarfish and feeble Nicaraguans.) In Grant’s estimation, the war was fought to liberate nonslaveholders, families exiled to poor land, who had few opportunities to better themselves or educate their children. “They too needed emancipation,” he insisted. Under the “old régime,” the prewar South, they were nothing but “poor white trash” to the planter aristocracy. They did as told and were accorded the ballot, but just so long as they parroted the wishes of the elite.18

✵ ✵ ✵

By 1861, both sides saw the other as an alien culture doomed to extinction. In a speech delivered in 1858, the same year as Hammond’s famous mudsill oration, William H. Seward, the leading New York Republican who was to serve in Lincoln’s cabinet, coined the term “irrepressible conflict.” For Seward, free labor was a higher form of civilization, practiced by the “Caucasians and Europeans.” He blamed slavery on the Spanish and Portuguese, and reduced all of South America to a land of brutality, imbecility, and economic backwardness. Toppling slavery in the U.S. South, in Seward’s grand historical schema, was merely an extension of the continental march of Anglo-Saxon civilization. The two class systems—slave and free—were locked in a battle for domination, and only one would survive.19

Of course, southern ideologues argued the exact opposite. Slavery was a vigorous and vibrant system, they insisted, and more effective than free labor. With a docile workforce, the South had eliminated conflict between labor and capital. Southern intellectuals alleged that the laboring class in the northern states was large, disruptive, jealous of the rich, and endowed with unwarranted political privileges. As Hammond and others saw it, the notion of equality had become the most deceptive fiction of the times. The very freedom “to think, feel and act,” a writer warned in Charleston’s Southern Quarterly Review, nurtures passion and provokes “unholy desire.” That “unholy desire” was the longing for social mobility. Slaves were content in their menial lot, many believed. In this strange reversal of the American dream, the South’s superiority arose, then, most ironically, from its absence of class mobility.20

Secessionists painted a dire picture of class instability above the Mason-Dixon Line. In the North, a writer contended in a Virginia magazine in 1861, “people are born, bred and educated to their leveling views,” which might “reverse the condition of the rich and the poor.” Education and class equality itself was seen as subversive, and Helper’s Impending Crisis of the South was attacked as incendiary. Men were arrested, and some hanged, for peddling his book. Worried elites urged Confederate leaders to “watch and control” poor whites, “permitting them to have as little political liberty as we can, without degrading them.”21

Not surprisingly, evidence exists to prove that southern whites lagged behind northerners in literacy rates by at least a six-to-one margin. Prominent southern men defended the disparity in educational opportunity. Chancellor William Harper of South Carolina concluded in his 1837 Memoir on Slavery, “It is better that a part should be fully and highly educated and the rest utterly ignorant.” Inequality in education was preferable to the system in the northern states, in which “imperfect, superficial, half-education should be universal.” As the Civil War arrived, editors and intellectuals called for an independent publishing industry in the Confederacy, in order to shield its people from the contamination of Union presses.22

Confederates openly defended the idea that the planter class was born to rule. The “representative blood of the South,” the aristocratic elite, those of good patrician stock, were destined to have command over white and black inferiors. But for all their confidence about harmonious relations between the rich and poor in the South, many secessionists viewed nonslaveholders as the sleeping enemy within. White workingmen in places like Charleston were called “perfect drones,” whose resentments could potentially be marshaled against slaveowners. Antidemocratic secessionists dismissed the poor as the hapless pawns of crass politicians, willing to sell their votes for homesteads or handouts. In 1860, Georgia governor Joseph Brown prophesied that the new Republican administration would bribe a portion of the citizens with offices, while others predicted that Lincoln would dangle bounties and cheap lands, using flattery and lures to ensnare the “lower strata of Southern society.” It was in response to such projections that small slaveholders in South Carolina organized vigilante societies and “Minute Men” companies, mainly to intimidate nonslaveholders who might try to forestall secession.23

Some secessionists went out of their way to allay concerns over the loyalty of nonslaveholders. In 1860, James De Bow, the influential editor of De Bow’s Review, published a popular tract detailing the reasons why poor whites had every reason to back the Confederacy. He assured that slavery benefited all classes. Giving the mudsill theory an emphatic endorsement, he declared that “no white man at the South serves another as his body servant to clean his boots, wait on his table, and perform menial services in his household!” Besides, he wrote, wages for white workers were better in the South, and land ownership was more dispersed—which was patently untrue. He went on: class mobility was possible for nonslaveholders who scrimped and saved to buy a slave, especially a breeding female slave, whose offspring were “heirlooms” to be passed on to the next generation. If his promises of trickle-down economics were unconvincing, De Bow tacitly confirmed that slaves’ elevation meant nonslaveholders’ utter degradation. For these reasons, he said, the poorest nonslaveholder would readily “dig in the trenches, in defense of the slave property of his more favored neighbor.” Fear of dropping to the level of slaves would lead poor whites to fight.24

Disunion did not alleviate such fears. In the lower South, for example, there was no popular referendum on secession except in Texas. The upper South was in no hurry to bolt. The four states that left (Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Tennessee) did so only after Lincoln called for troops; all of these states contained significant numbers of pro-Union residents. West Virginians seceded from Virginia and rejoined the Union. Jefferson Davis secured the presidency without opposition, reducing his election to a symbolic vote, rubber-stamping the choice of the elite minority in the Confederate Provisional Congress.25

In addition to insulating the government from the people, a vocal contingent of delegates to the Confederate constitutional convention called for a repeal of the three-fifths compromise, instead counting slaves as whole persons for the purpose of representation in the Confederate legislature. This manner of representation benefited the states with the highest number of slaves. The South Carolinian novelist William Gilmore Simms, for one, thought that the border states, with their larger nonslaveholding populations, might “overslough” the cotton states. In that a slough was a swamp or mire, Simms was alluding to the mudsill-like nonslaveholders of the upper South, whose higher numbers would allow them to have more representatives than the slave-dominated states of the lower South. In the final draft of the Confederate constitution, the repeal of the three-fifths clause was voted down, but by the narrow margin of four to three states.26

In 1861, a nervous Georgian, who worried that slaveholders were a minority, proposed that the new state government should establish an upper house composed only of slaveholders, much like the English House of Lords. Conservative Georgia and Virginia delegates to their respective state conventions wished to curb the “swinish multitude,” but in the end they refused to tamper with the right to vote. In Virginia, some elitists recognized the problem that conscription posed and sought to deal with it. Nonslaveholders might refuse to fight in a war designed to protect the slaves of the rich. Virginian Edmund Ruffin privately proposed a solution for his state: a dual system of conscription. In his two-track class system, one would require nonelite white men to take up arms, and another for planters’ slaves, who would be impressed by the state and put to work for the army. Too bold and too honest in broadcasting the prevalence of social inequality, Ruffin’s radical plan was never adopted.27

The future did not bode well for southern patricians. If they remained in the Union, or suffered defeat at the hands of the Yankees, they faced extinction. The aristocracy would be washed away in a flood of northern mudsills and liberated slaves. Their own homegrown white trash were a problem as well. Presumably, without total victory, landless laborers and poor farmers might outbreed the elite class, and if corrupted by northern democratic ideas, they might overwhelm the planter elite at the ballot box.28

✵ ✵ ✵

Throughout the war, the unfair conscription policy sparked serious grievances. Early on, Florida’s governor, John Milton, felt that the law could not be enforced, that poor whites would not stand for a substitution system that favored those who could buy a man to do his fighting for him. Exemptions protected the educated: teachers, ministers, clerks, politicians, as well as men in needed industries. Once the lowly conscripts were in the ranks, officers looked down on them as “food for powder,” or compared them to “Tartars” and barbarians, which were the same slurs that elite southerners used to demean Lincoln’s ruthless hordes. An Alabama recruit fed up with such treatment said the obvious: “They think all you are fit for is to stop bullets for them, your betters, who call you poor white trash.”29

One odious feature of the draft was the “twenty slave law,” which granted exemptions to planters with twenty or more slaves. The provision shielded the already pampered rich man and his valuable property. Some nonslaveholders refused to fight for the protection of slavery, while others thought the wealthy should pay higher taxes to subsidize a war that benefited them most. Lower-class men wanted their material interests protected. Wealthy officers were readily granted furloughs, while common soldiers were expected to endure long terms of enlistment, jeopardizing the livelihood of families left behind. As one historian has concluded, poorer soldiers thought of themselves as “conditional Confederates.” This meant that poor farmers put their family’s well-being before their loyalty to the Confederate nation.30

Southern gentlemen might be expected to fight without steady pay, but their definition of chivalry created an unrealistic standard for the lower classes. Class identity divided the ranks throughout the war. The “layouts,” men who refused to volunteer or to appear for service once drafted, were rounded up by guards who were crudely called “dog catchers.” Substitutes came from the poorest class of men, and were generally despised by other soldiers.31

Desertion was common among poor recruits, so much so that by August 1863, General Robert E. Lee was pleading with President Davis to take action to curb it. Later that year, Davis issued a general amnesty to all men who returned. In other instances, while some soldiers were executed, most companies subjected deserters instead to humiliating punishments. They were put in chains or forced to wear a barrel. Vigilantes hunted down runaway conscripts, especially in North Carolina, which had the highest rate of desertion. A community in Mississippi seceded from the Confederacy, creating the “Free State of Jones” in the middle of a swamp; it was, quite literally, a white trash Union sanctuary in President Davis’s home state.32

Deserters stole food, raided farms, and harassed loyal soldiers and citizens. Pockets of poor men and their families had become the anarchists that upper-class southerners had long feared. In Georgia, late in the war it had reached the point that deserters were threatening to kidnap slaves or, worse, conspire with runaways. In 1865, the wives of Okefenokee renegades taunted authorities by claiming that their husbands would rise out of the swamp, armed and ready to steal as many slaves as they could round up, and then sell them to the Union navy.33

It is difficult to gauge what poor, illiterate soldiers thought of desertion, because they left no written records. But oral folk culture suggests that poor men openly joked about it. Desertion to them was part of the daily resistance to upper-class rule. One story making the rounds pitted a Georgia sandhiller against a North Carolina Tar-heel. Asked what he had done with a quantity of pitch, the Carolinian claimed he had sold it to Jeff Davis. Caught off guard, the sandhiller said, “What did old Davis want with all that for?” “Why,” the Tar-heel jibed, “you Georgians run so that he had to buy some to make you stick.”34

There is no way to know precisely how many men deserted. The official count from the U.S. provost marshal’s report was 103,400. This was out of a total of 750,000 to 850,000 men listed as in the army by the end of the war. But these numbers are only a small part of the story. Class divided soldiers in other ways. The Confederate army dragooned at least 120,000 conscripts. There were between 70,000 and 150,000 substitutes, mostly wretchedly poor men, and only 10 percent ever reported to camp. Another 80,000 volunteers reenlisted to avoid the draft. Finally, as many as 180,000 men were at best “reluctant rebels,” those who resisted joining until later in the war. Such resistance demonstrates that among average soldiers there was little evidence of a deep attachment to the Confederacy.35

Shortages in food fueled more discontents. As early as 1861, when planters were urged to plant more corn and grain, few were willing to give up the white gold of cotton. Consequently, food shortages and escalating inflation led to massive suffering among poor farmers, urban laborers, women, and children. One Georgian confessed that “avarice and the menial subjects of King cotton” would bring down the Confederacy long before an invading army could.36

More disturbing, through, the rich hoarded scarce supplies along with food. In 1862, mobs of angry women began raiding stores, storming warehouses and depots; these unexpected uprisings blanketed Georgia, with similar protests surfacing in the Carolinas. In Alabama, forty marauding women burned all the cotton in their path as they scavenged for food. A food riot broke out in the Confederate capital of Richmond in 1863. When President Davis tried to calm the women, an angry female protester threw a loaf of bread at him.37

Female rioters were, in this way, the equivalent of male deserters. They shattered the illusion of Confederate unity and shared sacrifice. In 1863, in the wake of the Richmond riot, Vanity Fair exposed the persistence of deep class divisions among the southern population. The pro-Union magazine published a provocative image with the article, “Pity the Poor Rebels.” It described how poor men were arbitrarily rounded up as conscripts, while the desperately poor “white trash” of the Confederacy scratched the words “WE ARE STARVING” over the “dead wall” that separated the North and South. The featured illustration had an unusual caricature of Jefferson Davis, reminiscent of Jonathan Swift’s antihero in Gulliver’s Travels. Here the Confederate president, in a dress and bonnet, is tied down by southern Lilliputians—tiny slaves. Either way, he is unmanned by greedy planters or female rioters. His wrists are chained, his dress unraveling—a sure sign that the Confederacy has had its mask of gentility removed.38

Wealthy women of the South often displayed indifference to the starving poor. When a group of deserters and poor mountain women ransacked a Tennessee resort in 1863, Virginia French, one of the guests, described the “slatternly, rough, barefooted women” who raced to and fro, “eager as famished wolves for prey.” Both shocked and amused, she wrote, “Two women went into a regular fist fight & kept it up for an hour—clawing & clutching each other because one had more than the other!” She found it equally bizarre when another woman stole Latin theology and French books. When asked directly, the thief justified her booty as the act of a good mother: “She had some children who were just beginning to read & … she wanted to encourage em!” An illiterate woman thus assigned value to the literary treasures she had taken. This might have aroused some sympathy, but for French the scene was simply more evidence of “Democracy—Jacobinism—and Radicalism” in its rudest form. The women were “famished” and had “tallow” faces, the men were “gaunt” and “ill-looking,” but the southern planter’s wife remained unmoved. White trash soiled all they touched, and deserved contempt, not pity.39

Class insularity prevailed among Richmond’s elite women too. By early 1865, First Lady Varina Davis had become “unpopular with the ladies belonging to the old families,” a clerk close to her husband confided to his diary. Those of “high birth” had decided to shun her and talked behind her back, remarking on her father’s supposed low-class origins. There were stories widely circulated of government officials and their wives dining on delicacies while the people starved.40

In contemplating the demise of the Confederacy, other writers expressed more dramatic concerns. Class reorganization would reduce honored mothers to the station of “cooks for Yankee matrons,” convert beloved wives into washerwomen for “Yankee butchers and libertines,” and transform devoted sisters into chambermaids for “Yankee harlots.” No matter how the situation was sized up, the fact that poor rural women had already lost everything scarcely mattered, because their suffering counted little compared to the unsullied women of the ruling class.41

✵ ✵ ✵

A different kind of symbolism hovered over Abraham Lincoln, who in unflattering descriptions was crowned the president of the mudsills. Though he was born in Kentucky, not far from Jefferson Davis’s birthplace, Honest Abe’s backcountry roots became fodder for his enemies. The one thing that separated Lincoln and Davis was class origin. Southern newspapers described Davis as one “born to command.” He was a West Pointer, a man of letters and polite manners. Lincoln, by contrast, was a rude bumpkin, the “Illinois ape,” and a “drunken sot.” Lincoln’s supposed virtue, his honesty (or honest parents), was code for a suspect class background. In 1862, a close ally, Union general David Hunter, told Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase that Lincoln was born a “poor white in a slave state.” He judged Lincoln too solicitous of slaveholders in the border states, “anxious for approval, especially of those he was accustomed to look up to.” His Kentucky home made him white trash, and his chosen residence in Illinois made him a prairie mudsill. Confederates had an easy time equating midwesterners with dirt farmers; to one Virginia artilleryman, they were all “scoundrels, this scum, spawned in prairie mud.”42

The mudslinging battle, however, ended up working in favor of the Federal side. Republicans and Union officers wore the mudsill label as a badge of pride, and made it a rallying cry for northern democracy. This strategy began even before Lincoln was elected. At a large rally in New York City, Iowa’s lieutenant governor gave an impassioned speech in which he praised the “rail splitter” as the best farmer for the job—a man willing to protect the “mudsill and mechanic.” And he joked that every Republican in his state had “made up their minds to cultivate mudsill ideas.”43

The New York publication Vanity Fair used satire to turn the tables on Confederate class taunts. Their writers not only deflated the southerner’s gallant self-image, but also had a field day defending his “groveling” foe with “lobby ears”—the mudsill. (“Lob” was another word for a rustic knave.) Imitating southern speechifiers and hack journalists, the magazine described Lincoln as the chief magistrate of the “Greasy Mechanics and Mudsills of the barbarian North.”

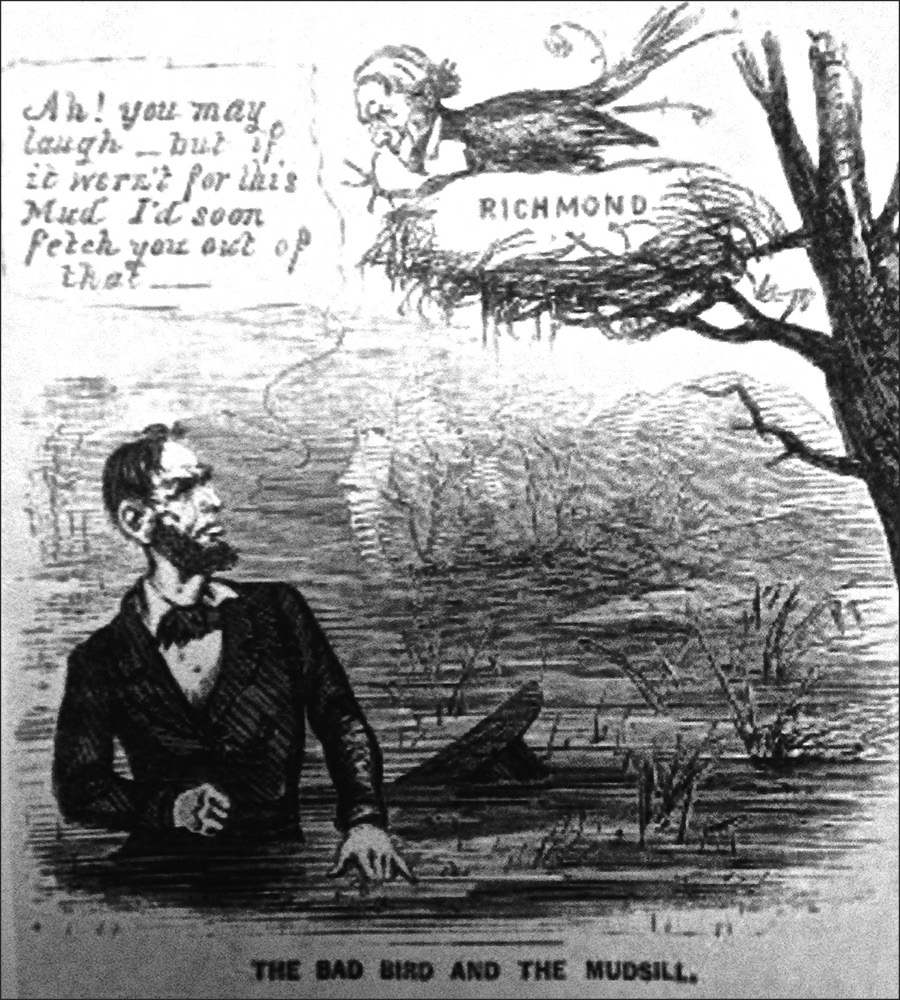

In Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1863), Lincoln, as caricatured, is literally a mudsill—stuck in the mud and unable to reach Jefferson Davis in Richmond.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 21, 1863

Jefferson Davis’s stilted oratory was equally subject to Vanity Fair’s withering satire. In a mock proclamation given after the First Battle of Bull Run, Davis issues an edict saying that his army would leave Washington in the dust, hang the “besotted idiot” Lincoln from the nearest tree, and topple New York City, turning the Seventh Regiment into body servants for Confederate officers. In his grandiose vision of easy victory, this parody of Davis declared that “mudsill soldiers” would offer little resistance, for “they will fly before us like sheep.” Southerners’ hyperbolic pronouncements were turned on their head; though begun as an insult aimed at plebian northerners, the mudsill designation proved most useful in ridiculing Confederate hubris. By 1863, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper had embraced the mudsill moniker, publishing a caricature of Lincoln up to his waist in mud, unable to reach the “bad bird” Davis in his Richmond nest.44

When General James Garfield, the future president, returned from the front in November 1863, he gave a speech at a meeting in Baltimore in defense of his fighting mudsills. He lauded the loyal men of Tennessee and Georgia who came out of “caves and rocks” to support the Union forces. The Confederacy was built, Garfield insisted, on a false idea, “not of a common government, but a government of gentlemen, of men of money, men of brains, who hold slaves.” It was a government resembling that of the aristocratic Old World. His audience of commoners roared when he called the two top Confederate generals “Count Bragg” and “My Lord Beauregard.” Roused by this reaction, Garfield addressed the friendly crowd as “you mudsills,” for they were benefactors of a government and society that promised class mobility and a genuine respect for the workingman. For Garfield, and for many others, the mudsills were the backbone of the Union. They were those “who rejoice that God has given you strong hands and stout hearts—who were not born with silver spoons in your mouths.” And proud mudsills they would remain.45

Because of the Confederacy’s class system, and the exploitation of poor whites by the planter elite, Republican congressmen and military leaders from the outset of the war argued in favor of a confiscation policy that went at the planters’ pocketbooks. It was in the border states, where allegiances were divided, that the policy of punishing rich Confederate sympathizers took shape. In Missouri, where irregular rebel guerrillas dismantled railroads and terrorized Unionist civilians, General Henry W. Halleck decided to mete out retribution in a highly selective manner. Rather than punish the entire citizenry, he ordered wealthy Missourians alone to pay reparations.46

In Halleck’s mind, the price of war had to be felt at the top. As refugees flooded into St. Louis—poor white women and children—Halleck and his fellow officers agreed that elites should cover the costs. Street theater complemented the army’s campaign, as Union officers sought to make punishments visible to the general public. Under Halleck’s stern but discriminating system of assessments, Missouri Confederates who refused to pay up were publicly humiliated by having their most valuable possessions confiscated and sold at auction. Military police officers entered homes and carted off pianos, rugs, furniture, and valuable books. The contrast between the rich and poor was stark. Displaced families from the Arkansas Ozarks showed up a hundred miles west of the Mississippi in the vicinity of Rolla. Led by a former candidate for governor, they formed a strange caravan of oxcarts, livestock, and dogs, altogether numbering over two thousand. The men were categorized by observers as white trash: “tall, sallow, cadaverous, and leathery.” They joined the starving, mud-covered women and barefoot children who comprised the South’s forgotten poor white exiles.47

Public shaming was another tactic used by the Union army. In New Orleans, General Benjamin Butler’s infamous Order No. 28 declared that any woman showing disrespect to a Union soldier would be treated as a prostitute, a punitive measure that denied the assumption of moral purity accorded upper-class women. More devastating was Order No. 76, by which Butler required all men and women to give an oath of allegiance; those who failed to do so had their property confiscated. Women’s equal political treatment exposed what lay hidden behind the “broad folds of female crinoline,” that men were hiding assets in their wives’ names. A victorious officer observed that in taking Fredericksburg in 1862, Union soldiers destroyed the homes of the wealthy, leaving behind dirt from their “muddy feet.” Vandalism was another way to disgrace prominent Confederates: seizing the symbols of wealth and status, smashing them, and leaving it behind as rubbish. The muddy footprint of the mudsill foot soldier was an intentionally ironic symbol of class rage.48

One person who took this message to heart was Andrew Johnson of Tennessee. As a military governor, Johnson became the bête noire of Confederates, the only U.S. senator from a seceding state to remain loyal to the Union. His loyalty earned him a place on the Republican ticket as Lincoln’s running mate in 1864. Johnson, an old guard Jacksonian Democrat, felt no constraint in voicing his disgust with the bloated planter elite. By the time he took over as military governor, he was already known for his confrontational style, eager to duke it out with those he labeled “traitorous aristocrats.” He vigorously imposed assessments to pay for poor refugee women and children, who he claimed were reduced to poverty because of the South’s “unholy and nefarious rebellion.” Not surprisingly, Johnson’s detractors looked upon the once-lowly tailor as undeserving white trash. He had a reputation for vulgarity in the course of his stump speeches. One politician he ran against before the war went so far as to call him “a living mass of undulating filth.” If Lincoln was white trash in the eyes of genteel southerners, Johnson looked worse.49

By the time General William T. Sherman orchestrated his famous March to the Sea in 1864, Union leaders believed that only widespread humiliation and suffering would end the war. Turning his army into one large foraging expedition, Sherman made sure his men understood the class dimension of their campaign. The most lavish destruction occurred in Columbia, South Carolina, the fire-eaters’ capital, where the most conspicuous planter oligarchy held court. In tiny Barnwell, sixty miles south of Columbia, Brevet Major General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick of New Jersey staged what he called a “Nero’s ball,” forcing the southern belles of the town to attend and dance with Union officers while the town burned to the ground.50

In justifying his violent course of action, Sherman revived one of Thomas Jefferson’s favorite terms for tackling class power. That word was “usufruct.” Sherman contended that there was no absolute right to private property, and that proud planters only held their real estate in usufruct—that is, on the good graces of the federal government. In theory, southerners were tenants, and as traitorous tenants, they could be expelled by their federal landlords. Jefferson had used the same Roman concept to develop a political theory for weakening the hold of inherited status and protecting future generations against debts passed on by a preceding generation. Sherman went further: property did not exist without the sanction of the federal government. His philosophy not only rejected states’ rights, but equated treason with a return to the state of nature. The southern oligarchy would be shorn of its land and class privilege. The only way for elite Confederates to protect their wealth was to submit to federal law.51

Union generals and their senior officers expected the cotton oligarchy to fall along with Davis’s administration. They were convinced that class relations would radically change in the aftermath of the war. A kind of missionary zeal shaped this strain of thinking. After the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, in 1865, Chaplain Hallock Armstrong sized up what he called “the war against the Aristocracy,” predicting in a letter to his wife that dramatic change was coming to the Old South. It was not slavery’s demise alone that would transform society, he said, but increased opportunities for “poor white trash.” He assured her that the war would “knock off the shackles of millions of poor whites, whose bondage was really worse than the African.” He observed their wretched conditions, appalled that generations of families had never seen the inside of a classroom.52

Many others recognized that it would be an insurmountable task to raise up the poor. A New York artillery officer named William Wheeler encountered ragged refugees in Alabama, and found it hard to believe that they could be classed as “Caucasians,” or considered the same “flesh and blood as ourselves.” Some Union men were prepared to encounter cadaverous poor whites in the southern backwaters, but they were surprised to see these people in the Confederate ranks. They described deserters, prisoners, and Confederate prison guards as seedy, slouching, ignorant, and oddly attired. Soldiers in the western theater were taken aback by the mud huts they espied along the Mississippi. The North’s mudsills seemed like royalty compared to the South’s truly mud-bespattered swamp people. 53

Mud could well be the central image in sizing up the cost of this war to Union and Confederate sides alike. There was no glamour, only tedious muddy marches, food shortages, foraging (which often entailed stealing from civilians), and the inhuman conditions that prevailed in fetid muddy camps. Union and Confederate dead alike were hastily laid to rest in shallow, muddy mass graves.54

But it was the “foul mudsill” in wartime propaganda that captured the political imagination on both sides. “Mudsill” joined other Confederate slurs for Union men: vagabonds, bootblacks, and northern scum. And we mustn’t forget Jefferson Davis’s insult of choice: “offscourings of the earth.” By adopting such a vocabulary, rebels could imagine northern soldiers as Lincoln’s indentured servants, low-class hirelings. To convince themselves of easy victory, Confederates insisted that the Federal army was filled with the “trash” of Europe, rubbish flushed from northern city jails and back alleys, all brought together with the clodhoppers and dirt farmers from interior sections of the Union. For their part, northerners perceived the bread riots, desertions, poor white refugees, and runaway slaves as firm evidence of a fractured Confederacy. In this way, North and South each saw class as the enemy’s pivotal weakness and a source of military and political vulnerability.55

Both sides were partially right. Wars in general, and civil wars to a greater degree, have the effect of exacerbating class tensions, because the sacrifices of war are always distributed unequally, and the poor are hit hardest. North and South had staked so much on their class-based definitions of nationhood that it is no exaggeration to say that in the grand scheme of things, Union and Confederate leaders saw the war as a clash of class systems wherein the superior civilization would reign triumphant.

Union men had a way of identifying “white trash” with the dual bogeymen of southern poverty and elite hypocrisy. They saw secession as a fraud perpetrated against hapless poor whites. A Philadelphia journalist had the best, or at least the most original, putdown of the Confederacy’s overproud social system when he directed Jeff Davis’s government to put a slave on their five-cent stamp; for only then, he argued, would “poor white trash” be able to “buy the chattel cheap.” But he didn’t let his fellow northerners entirely off the hook either. Little separated northern mudsills from southern trash. Neither class gained much when reduced to cannon fodder.56