White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (2016)

Part III

THE WHITE TRASH MAKEOVER

CHAPTER TWELVE

Outing Rednecks

Slumming, Slick Willie, and Sarah Palin

A dangerous chasm in the classes is alive and well in the United States of America. Don’t let anybody tell you it’s not.

—Carolyn Chute, The Beans of Egypt, Maine (revised, 1995)

The Bakker scandal was not enough to stop the stampede toward white trash and redneck chic that prevailed in the eighties and nineties. Margo Jefferson in Vogue called the new rage “slumming.” One of the most surprising confessions in this vein came from John Hillerman, the American actor who played the prim and proper English butler Jonathan Quayle Higgins III on Magnum, P.I. Hillerman said that when he received fan mail from England, where he was claimed as one of their own, he wrote back, “I hate to disappoint you, but I’m a redneck from Texas.”1

A growing chorus sought to clean up the image, to make “redneck” a term of endearment. Lewis Grizzard, who made a name for himself as a redneck journalist, thought it was time to stop mocking rednecks. He praised the 1993 antidiscrimination ordinance in Cincinnati that made hillbilly a protected class, and he hoped that Atlanta would pass a similar law for rednecks in anticipation of the 1996 Summer Olympics. In Florida, a man was charged under the Hate Crime Statute in 1991 for defaming a policeman by calling him a cracker. For Grizzard, “redneck” meant “agriculturalist,” a person like his father who worked outside and acquired an uneven tan before there was sunscreen. He was wrong, of course, as the long chronology catalogued here has shown.2

A certain ambiguity remained. Redneck, cracker, and hillbilly were simultaneously presented as an ethnic identity, a racial epithet, and a workingman’s badge of honor. A North Carolina journalist neatly summed up the identity confusion: “If you think you’re a redneck, you think you’re hardworking, fun-loving and independent. If you don’t think you’re a redneck, you think they’re loud, obnoxious, bigoted and shallow.” Added to the article was a pop quiz featuring questions about NASCAR, food, and TV’s Hee Haw, as if by a simple computation right answers could distinguish the “real Bubbas from the wanna-bes.”3

To be sure, breeding remained paramount in considerations of identity. In 1994, one irate journalist insisted that the Georgia politician Newton Leroy Gingrich was no redneck: he was born in Pennsylvania, had no southern accent, had served as a college professor, and got elected to Congress by suburbanites of Atlanta, many of them Yankees. This newsman’s expertise came from the fact that he was “kin to a great many of that breed.” Besides, he chided, “Gingrich wouldn’t last half an hour in a room of genuine rednecks.” You were a dyed-in-the-wool redneck or you weren’t. By this measure, neither Gingrich nor David Duke, the former Klan member who ran for governor of Louisiana in 1991, was a redneck. Duke was disqualified because he loved un-American Nazi salutes. Submitting to plastic surgery to make himself too pretty was also out of character. “No good ole Southern boy would dream of such a thing. It’s unmasculine, un-Southern.” This was the view of Jeffrey Hart, a conservative intellectual from Dartmouth College and former speechwriter for Presidents Nixon and Reagan.4

✵ ✵ ✵

Redneck was no longer the exclusive province of country singers. It had become part of the cultural lingua franca, a means of sizing up public men, and a strangely mutated gender and class identity. Nor were women silent in this debate. Two prominent female writers earned acclaim in the modern genre of white trash fiction. In the tradition of William Faulkner and James Agee, Dorothy Allison and Carolyn Chute offered unsparing accounts of rural poverty. Allison creatively reconstructed the conditions she knew from her early years in Bastard Out of Carolina (1992), while Chute, a working-class, college-educated writer from Portland, told of trailer trash in rural Maine in her breakout book, The Beans of Egypt, Maine (1985). What set these writers apart was that they wrote from within their class, not as outside observers; they were outing themselves, and knew precisely how to describe poor women’s experiences. Class and sexuality remained their dominant themes, and neither sugarcoated her subjects as good ol’ girls. What they showed instead was that women cannot wear “white trash” or “redneck” as a badge of honor.5

Allison is the better writer. That said, a spare prose may have been intentional for Chute. She captures events as they are happening, offering few insights into the inner life of her white trash subjects. The Beans are a sprawling extended tribe who take over the underbelly of Egypt. They are an assorted lot. There is Beal and his mother, Merry Merry Bean, the latter of whom is crazy and kept locked in a tree house. Reuben is a violent drunk who ends up in prison; Auntie Roberta pops out babies like the rabbits she skins and eats. Reuben’s girlfriend, Madeline, endures beatings at his hand. The characters’ only talents are shooting and procreating. Beal sleeps with Roberta, and some of her children may be his. She, meanwhile, would never win any awards for mothering, allowing her babies to roam at will and to spit, hiss, and swallow pennies. Beal rapes (or doesn’t rape) his neighbor Earlene Pomerleau, who becomes his wife, though he continues to sleep at his aunt’s. Madeline parades around in flimsy halters that let her breasts fall out.6

Earlene is a step ahead of the Beans in class terms, at once disgusted by and attracted to them. She compares her first sexual encounter with Beal to being mauled by a bear. She is horrified by his large feet. As she completes the sex act, she “pictures millions of possible big Bean babies, fox-eyed, yellow-toothed, meat-gobbling Beans.” Beal injures his eye at work, loses his job, and is racked by pain and a range of physical disabilities, but still he forbids Earlene to get food stamps. He refuses to go to a hospital until he is finally carried away by rescue workers. “I ain’t worth a piss,” the broken man says, scowling. He dies in a hail of police bullets after shooting out the windows of a wealthy family’s home. Earlene watches him fall, the gun clasped in his hand.7

The Beans are waste people. Their women are breeders. They talk about Bean blood, and they all look alike. Earlene’s father damns the Beans as uncivilized predators: “If it runs, a Bean will shoot it. If it falls, a Bean will eat it.” Earlene’s father is superior to these “tackiest people on earth,” he believes, because they inhabit an old trailer, while he built his own house. As to the womenfolk, he singles out Roberta, muttering that there should be a law that after nine children with no husband, “you get the knife,” that is, “tyin’ the tubes.” And when Reuben is taken away by the police, he voices the hope that they will “hog-tie the rest of the heathens.” What he means is: round up the children and exterminate them before they become “full-blown Beans.”8

In The Beans of Egypt, Maine, class warfare is played out at the lowest level. The middle class has no meaningful presence in the book: all that distinguishes the Pomerleaus from the Beans is Gram’s religious discipline and the fact that Earlene’s dad possesses artisan skills. Class is vividly shown when Earlene’s father insists on patrolling the driveway dividing the two properties. He commands Earlene, “Don’t go over on the Beans’ side of the right-of-way. Not ever!” But of course she does. He loses his daughter to the other side.9

Chute’s reception as a writer was often conflated with the life she led. With some condescension, she was praised for her “apparent ignorance of literary tradition,” which magically preserved a “vigorous originality.” Though compared to Faulkner, she had not read a single one of his novels until after reviewers noted the similarity between her Beans of Egypt and the Mississippian’s work. A reviewer for Newsweek saw her characters as “candidates for compulsory sterilization,” where “malevolent infants of doubtful paternity litter the floor.” In interviews, Chute talked about her impoverished past, and insisted that she retained a personal bond with “my people.” She explained, “Your material is what you live.”10

Her husband, Michael, an illiterate laborer, was a conduit to “her people.” The stories he told of rural characters influenced her writing. She herself had worked on a potato farm, in chicken processing, and in a shoe factory. Growing up in a working-class neighborhood in a suburb of Portland, she dropped out of high school, later taking classes at the University of Southern Maine. Her father was from North Carolina, which gave her southern roots. All of this contributed to the deeply political underpinnings of her books. She rejected the idea that anyone could escape the cycle of poverty—not if it meant leaving one’s “homeland,” “family,” and “roots.” The tribal nature of poor whites was their strength. The sense of place and of land was their only ballast.11

Over the next fifteen years, Chute’s politics sharpened. In 1985, she did not call herself a redneck, but by 2000 she did. She lived off the grid, without modern plumbing, and until 2002 without a computer; she continued to wear work boots and bandanas. By now, “redneck” was a symbol of working-class populism for Chute. She organized her own Maine militia group, supported gun rights, and became an outspoken critic of corporate power. There was, she wrote in a postscript to the revised version of The Beans of Egypt in 1995, a “dangerous chasm in the classes [that] is alive and well in the United States of America.” The Beans were no longer ordinary people trying to survive; they were symbols of an approaching class war and a “crumbling” American dream.12

Dorothy Allison displayed just as much of an interest in class as Chute. She tells the story of difficult and sometimes violent relationships between men and women. Her female characters are less likely victims, swept up in circumstances, in the manner of Chute’s female Beans; Allison’s women have more material resources and greater support from their family members. But both writers depict emotionally stunted poor white men and recognize that everyday burdens fall more heavily on their women.13

In Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, young Anne “Bone” Boatwright endures physical and sexual abuse at the hands of her mother’s second husband, Daddy Glen Waddell. In the town of Greenville, South Carolina, as it is for the Beans of Egypt, Maine, the Boatwrights are despised. Daddy Glen’s festering hatred of Bone comes from deeply lodged feelings of humiliation. He comes from a middle-class family, and he is the one member who never amounted to anything. He is a manual laborer and longs for a home like those of his brothers, one a dentist, the other a lawyer. “Nothing I do goes right,” he grouses. “I put my hand in the honey jar and it comes out shit.” He is jealous of Earle Boatwright’s prowess with women too. Unlike the Beans, though, the Boatwright men tend to be affectionate and protective of the women and children in their extended family.14

Allison is fascinated by the thin line that separates the stepfather’s family from the mother’s; they might have more money, but they’re shallow and cruel. Her cousins whisper that their car is like “nigger trash.” Like Chute’s Pomerleaus, they feel compelled to snub those below them. It is shame that keeps the class system in place.15

By the end of the novel, Bone frees herself from Glen, and in the process loses out to him when her psychically damaged mother decides to abandon the family and take off for California with him. In running away, her mother repeats the strategy of crackers a century earlier: to flee and start over somewhere else. Ruminating on her mother’s life—pregnant at fifteen, wed then widowed at seventeen, and married a second time to Glen by twenty-one—Bone wonders whether she herself is equipped to make more sensible decisions. She won’t condemn her mother, because she doesn’t know for certain that she will be able to avoid some of the same mistakes.16

The lesson here is that the choices people make are both class- and gender-charged. Allison’s story serves as a reminder that many more people—women especially—remain trapped in the poverty into which they are born; it is the exception who becomes, like the author Allison, a successful person capable of understanding the poor without condemning. The American dream is double-edged in that those who are able to carve out their own destiny are also hard-pressed not to condemn those who get stuck between the cracks. As it is with the character Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, an awareness of the routine nature of injustice is most forcefully depicted when it is seen through the eyes of a child.

✵ ✵ ✵

As the literary canon took on a new dimension with the rise of a talented generation of white trash writers, Americans returned another southerner to the White House in 1993. With Bill Clinton, the national spotlight focused once more on the uneasy relationship between class identity and American democracy. The boy from modest beginnings in Hope, Arkansas, had won a Rhodes Scholarship, was a Yale Law School graduate, and served as the governor of his state—in short, the American dream. William Jefferson Clinton was a perfect example of what his namesake, the man from Monticello, had formulated in 1779: raking from the rubbish a deserving youth who could eventually join the nation’s aristocracy of talent. In his Fourth of July speech in his first year as president, Clinton recounted the story of how thirty years earlier he had met President Kennedy in the Rose Garden of the White House, shaking his hand, standing in awe as a “boy from a small town in Arkansas, with no money and no political connections.”17

The Clinton saga was a blend of Charles Dickens and Dorothy Allison. He did not grow up in a financially secure middle-class nuclear family of the fifties. Rather, his father had died three months before he was born, and his mother left him in the care of grandparents and great-grandparents while she attended nursing school. “The strength of our family could not be measured by the weight of our wallets,” he proudly declared on Independence Day in 1993. But as the public learned from his mother, Virginia, there was a darker side to Bill’s childhood. In the biographical film shown during the Democratic National Convention, Clinton’s fractured roots were exposed. He may have taken the name of his stepfather, but as a fourteen-year-old found he had to stand up to him. Roger Clinton was a car dealer and a gambler; he drank too much, and he became violent. One day, Bill quietly told him, “Don’t ever, ever lay your hands on my mother again.” But like Chute’s and Allison’s treatment of their male characters, he was not without compassion, saying of his stepfather’s problem, “He didn’t think enough of himself.” He had internalized that sense of white trash shame.18

On the campaign trail, Clinton quoted Jefferson, and staged his ceremonial inaugural journey to Washington from the top of Jefferson’s “little mountain.” At the Republican convention, ex-president Reagan had taken the opportunity to question the pretensions of the boy from Hope, dismissing the idea that Clinton was the heir of either Kennedy or Jefferson. In a classic quip, he modified lines that the Texan Lloyd Bentsen had used against Dan Quayle of Indiana in the 1988 vice presidential debate, after the latter had compared himself to a young, untested JFK, with whom Bentsen had served. “Senator,” Bentsen bellowed, “you’re no Jack Kennedy.” With mock gravity, Reagan deployed his own version of Bentsen’s iconic putdown, this time applying the sentiment to then-governor Clinton. “I knew Thomas Jefferson,” Reagan said. “He was a friend of mine. And, Governor, you’re no Thomas Jefferson.”19

What, then, was Bill Clinton? He embodied certain stereotypes: his cholesterol-rich dining habits, the wife-beating story about his mother, and allusions to dirt-poor shacks in the Arkansas hills. To add fuel to the fire, a grinning, still-campaigning Clinton was photographed with an Illinois (not Arkansas) mule named George, and a mule named Bill got press when it strolled down Pennsylvania Avenue as part of the Clinton inauguration parade.20

Arkansas was ranked forty-seventh in per capita income in 1992, and its legacy as a state scarred by “redneck benightedness” lingered on. By calling on a Jefferson or a Kennedy in his speeches, Clinton was attempting to distance himself from his home state and class background. His mentor had been Arkansas senator J. William Fulbright, a liberal champion of education and a statesman of real note, but he still needed national icons for his presidential run. Even in 2004, as a popular and productive ex-president, Clinton was still trying to balance the extremes of his upbringing and his ambition, as Texas pundit Molly Ivins felt when she reviewed his thick memoir: “You just have to stand back and admire the sheer American dream arc of this hopelessly hillbilly kid.”21

Bill Clinton was not a hillbilly, nor a redneck, but he did claim at the Democratic National Convention to have a “little bit of Bubba” in him. Bubba Magazine was issued in his honor, and the first cover displayed a photograph of Clinton wearing a cap and holding a beer. In the words of humorist David Grimes of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, this act of self-identification put Clinton in a long line of Bubba presidents, including Andrew Jackson, Lyndon Johnson (the biggest Bubba of them all), and Jimmy Carter, the last of whom “felt extremely guilty about it.”

Clinton’s election did what the earlier nonelite southern presidents could not, turning crackers and rednecks into something that mainstream America could embrace. The Texas-born New York editor of Bubba Magazine described Bubba as someone who was patriotic, religious, enjoyed a dirty joke, but “cut across socioeconomic groups” in expressing an identity. Bubba wasn’t regionally based, then, and defied stereotypes about cultural upbringing normally associated with an ethnic identity. To be a Bubba was to adopt a leisure self, a thing put on and worn like a pair of dungarees or a trucker’s cap. Take off your suit and tie and dress down à la redneck—one might call it white trash slumming. It was just one more attempt to downplay class by anointing (and electing) Bubba as the new common man. Or so innovators in democratic parlance preferred as the Clinton era took shape.22

Clinton acquired other, less folksy nicknames, of course. “Slick Willie” was a slur that dogged him all the way from Arkansas to the White House. Of the issues that attached to him—smoking marijuana (with or without inhalation), dodging the draft, an alleged affair—Clinton issued denials, offered earnest-seeming explanations, but always came across as somewhat less than forthright. Here he was portrayed as a smooth talker, even a con man—“Slick Willie” was a name with southern and rural flavor. There was in Clinton’s rise the backdrop of a tawdry southern novel, as Paul Greenberg of the Arkansas Democrat discovered: Clinton’s finesse at verbal dodges suggested a man ducking into all the available rabbit holes. It was Greenberg who first bestowed the ignominious title on the boy from Hope back in 1980. Another syndicated columnist saw something deeply southern in the moniker: it suggested the liberal politician’s reflex—in the South, honesty could derail a career.23

Clinton could not help but be defined by his origins. Even with his gift for gab, he was never as polished or, well, as slick as Reagan, who was known as the “Teflon-coated president.” In his first year in office, when Clinton appeared momentarily to fumble, an editorialist wrote that Slick Willie was looking more like Sheriff Andy Griffith’s sidekick Barney Fife. Image was everything, and politicians were always fair game, no matter how shallow, fleeting, or obnoxious the label pasted on them in print or cartoon was. The game in the 1990s was to find an image that placed Bill Clinton in a more favorable light and brushed the dirt from his jeans. What might be Clinton’s “Old Hickory” moment? As it turned out, he was saved by Elvis.24

Clinton was not in the least reticent about cultivating the Elvis image. He sang one of the King’s songs on a New York City news program, and during an interview with Charlie Rose jokingly appealed to the press, “Don’t Be Cruel.” What really did it for him, though, was an appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show playing his saxophone rendition of “Heartbreak Hotel.” Clinton had revived the old southern political strategy—as Jimmy Carter could not do—of singing and swinging his way into office. His vice president, Al Gore of Tennessee, regaled the Democratic National Convention by confessing that the moment at hand represented the fulfillment of his longtime wish to be the warm-up act for Elvis. As he made his final campaign swing, Clinton added a line to his speeches, parodying himself by telling each audience that he was communing with Elvis. Incumbent president George H. W. Bush was so annoyed with reporters’ love affair with the Arkansas Elvis that his staff hired an Elvis impersonator to crash the Democrat’s campaign appearances. Clinton took it all in stride and invited his own Elvis performer to the inauguration.25

“Elvis is America,” explained one member of Clinton’s staff. The fifties that Reagan had tried to recapture with nostalgic images of small-town U.S.A. was once again associated with fun-loving teenagers—less political than their parents. Clinton-the-marijuana-smoking-draft-dodger was in this way extracted from the dangerous sixties and rebranded as a child of the less contentious fifties. He wished to build a bridge to the southern working class, to make himself a son of the South in the best way imaginable. Being an Elvis fan was a more neutral place to be within a divided electorate—a youthful role that played much better than Bubba, and a hipper way for Clinton to channel his southern-boy image.26

In 1994, Bill Clinton’s controversial reputation as white trash was reinforced by a campaign photograph of him with an Illinois mule.

“Seen as ‘White Trash’: Maybe Some Hate Clinton Because He’s Too Southern,” Wilmington, North Carolina, Star-News, June 19, 1994

No amount of amiability, however, could quell the hatred of conservative Republicans on losing the White House. Beltway reporters said they had never seen such vitriol before. The attacks on President Clinton seemed disrespectful of the office, highly personal, and relentless. In 1994, journalist Bill Maxwell of Florida, an African American, said he thought he knew why. He saw something familiar in the tone of the Clinton bashing, and it had to do with his being seen as white trash. Reagan press aide David Gergen and the effusive speechwriter Peggy Noonan saw their President Reagan as a transcendent father figure, partaking of the family feeling inspired by a British king. To Reagan’s admirers, Clinton was unworthy, an impostor whose upbringing besmirched the office: the prince had been replaced by the pauper.27

To Maxwell’s mind, Clinton’s earthiness, his southernness, was seen as being bred into him from his mother, Virginia. She had published a memoir, and her story was grim: her mother was a drug addict, her childhood was one of deprivation, and she was married four times. Her appearance borrowed from trailer trash: “skunk stripe in her hair, elaborate makeup, colorful outfits and racing form in hand.” (Traces of Tammy Faye hung about her.) In the eyes of his enemies, said Maxwell, Clinton was his mother’s son, a kind of bastard breed that fell short of representing the right “pedigree for a U.S. president.”28

By the time the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke in 1998, Clinton’s enemies were primed to portray the flawed president as a character in a Tennessee Williams play. “Slick Willie” had finally been caught in a tawdry sexual escapade suited to a trailer park—he had befouled the Oval Office. Independent counsel Kenneth Starr claimed that his official investigation was not about sex, but about perjury and the abuse of power, yet his final report mentioned sex five hundred times. Harper’s Magazine contributing editor Jack Hitt claimed that Starr was intent on writing a “dirty book,” recording (and relishing) every trashy detail of a sad soap opera. President Clinton’s legal team countered that Starr’s sole purpose was to embarrass the president. This was white trash outing on the grand national stage. Impeachable offenses demanded the “gravest wrongs” against the Constitution, or “serious assaults on the integrity of the process of government,” if they were to rise to the standard of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” By recording every salacious detail, Starr was trying to equate high crimes with low-class lewdness.29

Conservatives were apoplectic at the thought that Clinton’s misdeeds could be compared with those of Thomas Jefferson—the DNA of the third president’s male line was tested the same year as the Lewinsky story broke. Science could now determine that the master of Monticello (or at least a Jefferson male with regular access to her—and who else could that be?) fathered the children of the Monticello slave Sally Hemings, the much younger half sister of Jefferson’s deceased wife. Distraught commentators twisted the facts of the case, offering up an odd collection of rationales in order to exonerate the third president from charges of immorality. One, Sally was beautiful (and Monica was cheap). Two, Clinton was an adulterer (and Jefferson was a widower of long standing). Three, Jefferson was a brilliant man whose words elevated him above his bodily urges (and the merely glib Clinton was unable to rise above his unimpressive origins). To conflate the impulses of Jefferson and Clinton was a leveling that upright Americans should not countenance.30

Another editor saw the Lewinsky episode differently. After Clinton survived the impeachment ordeal and emerged stronger and more popular, he looked for explanations. If hating Clinton was irrational, then so was loving him. It was the “Elvis principle,” the journalist concluded, that subliminal desire all Americans have for kings. JFK had Camelot; Reagan was Hollywood royalty; Clinton and Elvis (“the King” to his millions of fans) were “rags to riches” monarchs. The kind of kings Americans looked up to were men with a hard-to-explain sex appeal and a gentle hubris. The point was that a little white trashiness could be a blessing in disguise. In the appearance-driven world of modern American politics, arrogance of style carried weight, and repressed, suit-and-tie candidates such as Walter Mondale or Michael Dukakis were not in the same league as Clinton. To exude that redneck chic—to have a little Bubba—was better than being a dull, invisible, cookie-cutter politician indistinguishable from the pack.31

Figuring out Clinton remained a favorite pastime. In 1998, looking on with horror at the trumped-up presidential adultery scandal, the novelist Toni Morrison drew her own conclusions. The violation of privacy, the ransacking of the presidential office when he was “metaphorically seized and body searched” was for her the kind of treatment black men faced. No matter “how smart you are, how hard you work,” you will be “put in your place.” Clinton had overreached. He was “our first black president,” Morrison mused. The “tropes of blackness” were apparent in his upbringing in a single-parent and poor household, and in his working-class ways, his saxophone playing and love for junk food. This Clinton really was Elvis-like. He was not the redneck Elvis who still had devotees in the 1990s, but the “Hillbilly Cat” Elvis of the 1950s, the youth who transgressed the boundaries between black and white—something that was only possible to do in comfort among the lower ranks of southern society.32

Clinton’s title of “first black president” was reaffirmed at the 2001 Congressional Black Caucus Dinner. When Barack Obama ran for president in 2007, Andrew Young, the Carter adviser who had been a friend to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., said that Clinton was “every bit as black as Barack.” How strange was that: the son of a Kenyan was less black than a Bubba from Arkansas? Young was treating blackness as a cultural identity, and Obama’s childhood in Hawaii and Jakarta lacked Dixie roots. Kathleen Parker of the Washington Post, a southerner, saw confusion in figurative language, writing that all one had to do was to replace the sax with a banjo and Clinton became a pastiche of “white-trash tropes.” Journalist Joe Klein pushed the trope further in Primary Colors (1996), his thinly veiled novel about Clinton, who is called Jack Stanton in the book. Stanton violates the sexual taboo, sleeping with an underage black female, fathering an illegitimate child. In the Mike Nichols film based on Klein’s book, President Bubba was played by the unpolished John Travolta, instead of someone like the squeaky clean Tom Hanks. Was this fellow Stanton a symbol of blackness, or was he trailer trash?33

✵ ✵ ✵

Clinton’s embarrassing second term evidently wasn’t read as a cautionary tale among Republicans, who plunged ahead with their own (effectively) white trash candidate in 2008, Alaska governor Sarah Palin. The devastatingly direct Frank Rich of the New York Times referred to the Republican ticket as “Palin and McCain’s Shotgun Marriage.” Did the venerable John McCain of Arizona, ordinarily a savvy politician, have a lapse in judgment here? Slate produced an online video of Palin’s hometown of Wasilla, painting it as a forgettable wasteland, a place “to get gas and pee” before getting back on the road. Wasilla was elsewhere described as the “punch line for most redneck jokes told in Anchorage.” Erica Jong wrote in the Huffington Post, “White trash America certainly has allure for voters,” which explained the photoshopped image of Palin that appeared on the Internet days after her nomination. In a stars-and-stripes bikini, holding an assault rifle and wearing her signature black-rimmed glasses, Palin was one-half hockey mom and one-half hot militia babe.34

News of the pregnancy of Palin’s teenage daughter Bristol led to a shotgun engagement to Levi Johnston, which was arranged in time for the Republican National Convention. Us Weekly featured Palin on the cover, with the provocative title, “Babies, Lies, and Scandal.” Maureen Dowd compared Palin to Eliza Doolittle of My Fair Lady fame, in getting prepped for her first off-script television interview. Could there be any more direct allusion to her questionable class origins? The Palin melodrama led one journalist to associate the Alaska clan with the plot of a Lifetime television feature. The joke was proven true to life two years later, when the backwoods candidate gave up her gig as governor and starred in her own reality TV show, titled Sarah Palin’s Alaska.35

Palin’s candidacy was a remarkable event on all accounts. She was only the second female of any kind and the first female redneck to appear on a presidential ticket. John McCain’s advisers admitted that she had been selected purely for image purposes, and they joined the chorus trashing the flawed candidate after Obama’s historic victory. Leaks triggered a media firestorm over Palin’s wardrobe expense account. An angry aide categorized the Palins’ shopping spree as “Wasilla hillbillies looting Neiman Marcus from coast to coast.”36

The Alaskan made an easy and attractive target. Journalists were flabbergasted when she showed no shame in displaying astounding lapses in knowledge. Her bungled interview with NBC host Katie Couric represented more than gotcha journalism: Palin didn’t just misconstrue facts; she came across as a woman who was unable to articulate a single complex idea. (The old cracker slur as “idle-headed” seemed to fit.) But neither did Andrew Jackson run as an “idea man” in an earlier century, and it was his style of backcountry hubris that McCain’s staffers had been hoping to revive. Shooting wolves from a small plane, bragging about her love of moose meat, “Sarah from Alaska” positioned herself as a regular Annie Oakley on the campaign trail.

It was not enough to rescue her from the mainstream (what she self-protectively called “lamestream”) media. Sarah Palin did not have a self-made woman’s résumé. She could not offset the “white trash” label as the Rhodes Scholar Bill Clinton could. She had attended six unremarkable colleges. She had no military experience (à la navy veteran Jimmy Carter), though she did send one son off to Iraq. Writing in the New Yorker, Sam Tanenhaus was struck by Palin’s self-satisfied manner: “the certitude of being herself, in whatever unfinished condition, will always be good enough.”37

Maureen Dowd quipped that Palin was a “country-music queen without the music.” She lacked the self-deprecating humor of Dolly Parton—not to mention the natural talent. The real conundrum was why, even more than how, she was chosen: the white trash Barbie was at once visually appealing and disruptive, and she came from a state whose motto on license plates read, “The Last Frontier.” The job was to package the roguish side of Palin alongside a comfortable, conventional female script. In the hit country single “Redneck Woman” (2004), Gretchen Wilson rejected Barbie as an unreal middle-class symbol—candidate Palin’s wardrobe bingeing was her Barbie moment.

Her Eliza Doolittle grand entrance came during the televised debate with Senator Joe Biden of Delaware. As the nation waited to see what she looked like and how she performed, Palin came onstage in a little black dress, wearing heels and pearls, and winked at the camera. From the neck down she looked like a Washington socialite, but the wink faintly suggested a gum-chewing waitress at a small-town diner. Embodying these two extremes, the fetching hockey mom image ultimately lost out to what McCain staffers identified as both “hillbilly” and “prima donna.” She was a female Lonesome Rhodes—full of spit and spittle, and full of herself.38

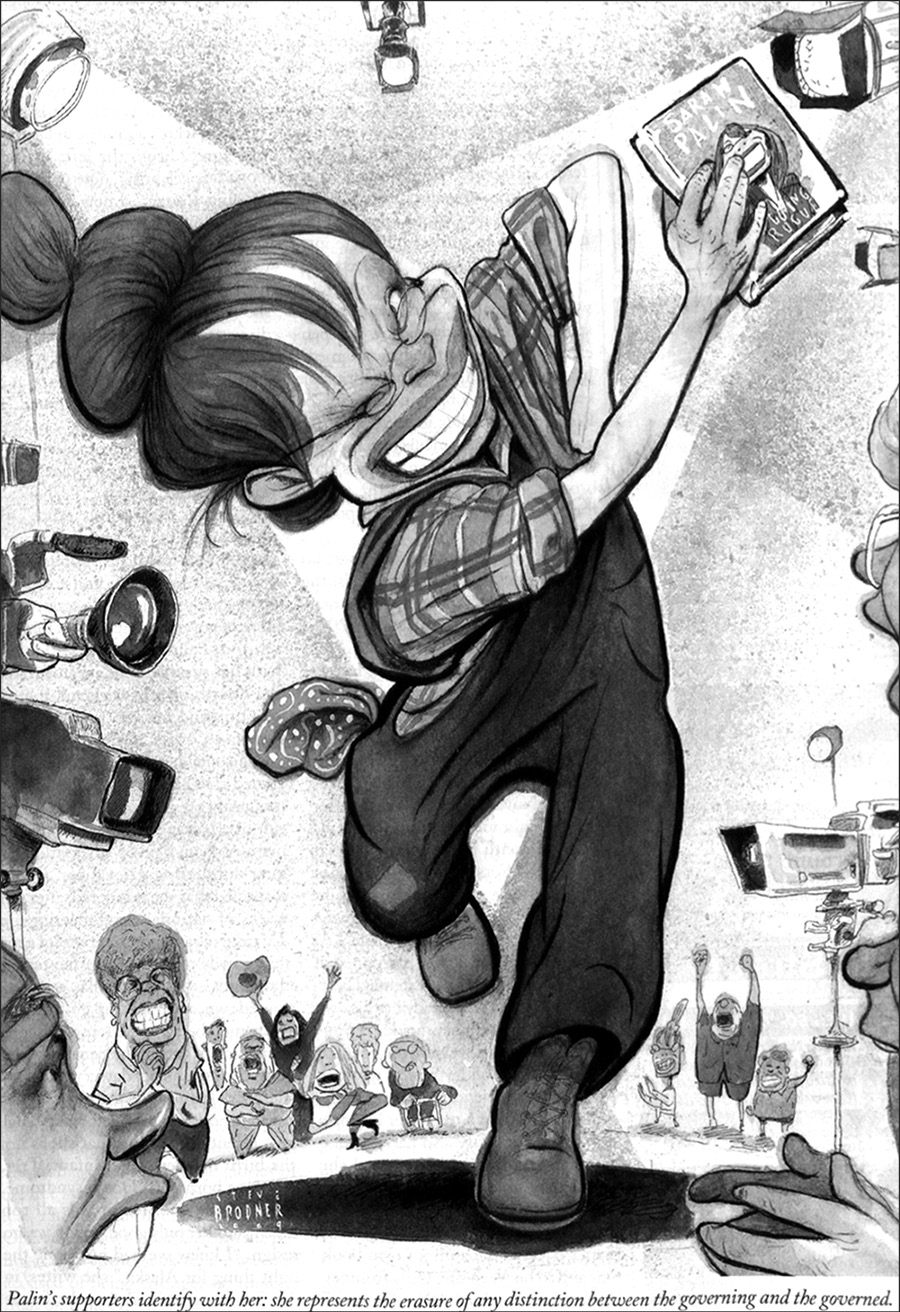

Steve Brodner’s caricature of Sarah Palin as the celebrity-seeking hillbilly, which appeared in the New Yorker in 2009.

New Yorker, December 7, 2009

Sex formed a meaningful subtext throughout Palin’s time of national exposure. In terms of trash talk, daughter Bristol Palin’s out-of-wedlock pregnancy was handled rather differently from Bill Clinton’s legendary philandering. Bloggers muddied the waters by spreading rumors about Sarah’s Down syndrome child, Trig: “Was he really Bristol’s?” they asked. A tale of baby swapping was meant to suggest a new twist on the backwoods immorality of inbred illegitimacy. Recall that it was Bill Clinton’s mother, Virginia, whose pedigree most troubled the critics. The legacy held: the rhetoric supporting eugenics (and the sterilization laws that followed) mainly targeted women as tainted breeders.39

Sarah Palin’s Fargoesque accent made her tortured speech patterns sound even worse. Former TV talk show host Dick Cavett wrote a scathing satirical piece in which he dubbed her a “serial syntax killer” whose high school English department deserved to be draped in black. He wanted to know how her swooning fans, who adored her for being a “mom like me,” or were impressed to see her shooting wolves, could explain how any of those traits would help her to govern.

We had been down this road before as citizens and voters. “Honest Abe” Lincoln was called an ape, a mudsill, and Kentucky white trash. Andrew Jackson was a rude, ill-tempered cracker. (And like Palin, his grammar was nothing to brag about.) The question loomed: At what point does commonness cease to be an asset, as a viable form of populism, and become a liability for a political actor? And should anyone be shocked when voters are swept up in an “almost Elvis-sized following,” as Cavett said Palin’s supporters were? When you turn an election into a three-ring circus, there’s always a chance that the dancing bear will win.40

By the time of the 2008 election, Americans had been given a thorough taste of the new medium of reality TV, in which instant celebrity could produce a national idol out of a nobody. In The Swan, working-class women were being altered through plastic surgery and breast implants to look like, say, a more modest, suburban Dolly Parton. While American Idol turned unknowns into overnight singing sensations, the attention-craving heiress Paris Hilton consented to filming an updated Green Acres in The Simple Life, moving into an Arkansas family’s rural home. Donald Trump’s The Apprentice, billed as a “seductive weave of aspiration and Darwinism,” celebrated ruthlessness. In these and related shows, talent was secondary; untrained stars were hired to serve voyeuristic interests, in expectation that, as mediocrities, they could be relied on to exhibit the worst of human qualities: vanity, lust, and greed. In 2008, Palin underwent an off-camera “Extreme Makeover”—to borrow a title from one of the more popular such shows. McCain campaign advisers bought into the conceit of reality TV, which said that anyone could be turned into a pseudo-celebrity; in this instance, their experiment had the effect of reshaping national politics.41

After 2008, a new crop of TV shows came about that played off the white trash trope. Swamp People, Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, Hillbilly Handfishin’, Redneck Island, Duck Dynasty, Moonshiners, and Appalachian Outlaws were all part of a booming industry. Like the people who visited Hoovervilles during the Depression, eyeing the homeless as if they were at the zoo, television brought the circus sideshow into American living rooms. The modern impulse for slumming also found expression in reviving the old stock vaudeville characters. One commentator remarked of the highly successful Duck Dynasty, set in Louisiana, “All the men look like they stepped out of the Hatfield-McCoy conflict to smoke a corncob pipe.” The Robertson men were kissing cousins of the comic Ritz Brothers in the 1938 Hollywood film Kentucky Moonshine.42

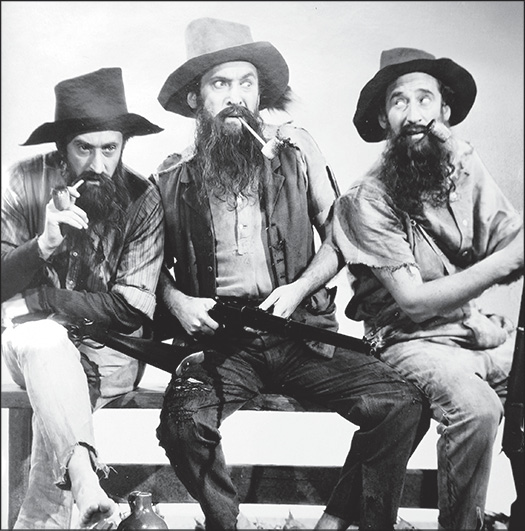

Kissing cousins. The comic Ritz Brothers from Kentucky Moonshine (1938) and their heirs, the male cast of Duck Dynasty, the highly popular A&E reality TV show.

Reality programming subsists on emotion-producing competition and outright scandal. The long-running Here Comes Honey Boo Boo was canceled in 2014, but only after it was discovered that Mama June Shannon was dating a convicted child molester; she next revealed that the father of two of her daughters was an entirely different convicted sex offender who had been caught in a sting on NBC’s voyeuristic To Catch a Predator. Though her young daughter Honey Boo Boo was the headliner, June was the real star of the show, the new face of white trash. No longer emaciated and parchment colored, as white trash past was imagined, she was a grossly overweight woman and the antithesis of the typical mom who prettified her grade-school daughter and dragged her to child beauty pageants. June claimed to have had four daughters by three different men, one whose name she claimed she could not remember. Her town of McIntyre, in rural Georgia, is a place of stagnant poverty: one-quarter of its households are headed by single females, and in 2013 the median family income in McIntyre was $18,243.43

As the gap between rich and poor grew wider after 2000, conservatives took the lead in white trash bashing. In Black Rednecks and White Liberals (2005), the economist and Hoover Institute fellow Thomas Sowell connected the delinquency of urban black culture to redneck culture. The book begins with a quote dating to 1956: “These people are creating terrible problems in our cities. They can’t or won’t hold a job, they flout the law constantly and neglect their children, they drink too much and their moral standards would shame an alley cat.” His assumption was that readers would associate the quote with a conventional racist attack. But it was aimed at poor whites living in Indianapolis, and reflected “undesirable” southern whites who lived in northern cities.

Sowell contended that there has been an unchanging subculture going back centuries. Relying on Grady McWhiney’s Cracker Culture (1988), a flawed historical study that turned poor whites into Celtic ethnics (Scots-Irish), Sowell claimed that the bad traits of blacks (laziness, promiscuity, violence, bad English) were passed on from their backcountry white neighbors. In Sowell’s odd recasting of the hinterlands, a good old eye-gouging fight was the seed of black machismo. Reviving the squatter motif, he downplayed the influence of slavery, and substituted for it a eugenic-like cultural contagion that spread from poor whites to blacks. He further argued that white liberals of the present day are equally to blame for social conditions, having abetted the destructive lifestyle of “black rednecks” through perpetuation of the welfare state.44

Another conservative blaming the poor for their problems is Charlotte Hays, whose 2013 book When Did White Trash Become the New Normal? was a “Southern Lady’s” gossipy screed against obesity, bad manners, and the danger of national decline when society takes its “cues” from the underclass. Hays expressed her horror that Here Comes Honey Boo Boo attracted more viewers than the 2012 Republican National Convention. In her best imitation of a snooty matron complaining, “You can’t get good help anymore,” the author/blogger’s senses were affronted whenever and wherever she saw the disappearance of the rules of politeness. That a depressed minimum wage keeps millions in poverty is of no concern: she writes that the colonists at Jamestown and Plymouth understood that hard work might still require “a little starving.” If she was talking about the actual Jamestown, she should have said “a lot of starving” and a little cannibalism. Hays represents a good many people who persist in believing that class is irrelevant to the American system. It is, she insists, manners (alas, no longer practiced by one’s social inferiors) that determine the health of a civilization. “A gentleman is defined,” Hays writes, “in a way that a janitor could be considered one if he strove to do the right thing.”45

Sowell and Hays were responding to the cultural shift that began in the 1970s. Hays wished to banish identity politics entirely, which is why she mocked all kinds of white trash slumming. In its place, she imagined reviving old-fashioned manners—as if it were possible for class identity to be hidden under a veneer of false gentility. She wanted the pretense of equality, but offered nothing for closing the wealth gap. Sowell reimagined what Alex Haley started, in attempting to rewrite race as an ethnic identity and heritage—that is, something transmitted culturally from one generation to the next. With his revisionist pen, he cut the tie to Africa, the roots forged by Haley, and replaced the noble African American progenitor with a debased cross-pollinating power: degenerate crackers of white America.

A corps of pundits exist whose fear of the lower classes has led them to assert that the unbred perverse—white as well as black—are crippling and corrupting American society. They deny that the nation’s economic structure has a causal relationship with the social phenomena they highlight. They deny history. If they did not, they would recognize that the most powerful engines of the U.S. economy—slaveowning planters and land speculators in the past, banks, tax policy, corporate giants, and compassionless politicians and angry voters today—bear considerable responsibility for the lasting effects on white trash, or on falsely labeled “black rednecks,” and on the working poor generally. The sad fact is, if we have no class analysis, then we will continue to be shocked at the numbers of waste people who inhabit what self-anointed patriots have styled the “greatest civilization in the history of the world.”