Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche - Haruki Murakami (2003)

Part I. UNDERGROUND

TOKYO METROPOLITAN SUBWAY: MARUNOUCHI LINE (Destination: Ogikubo)

TRAIN A777

![]()

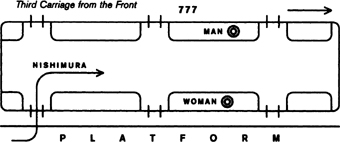

The team of Ken’ichi Hirose and Koichi Kitamura planted sarin on a westbound Marunouchi Line train destined for Ogikubo.

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Hirose was 30 years old at the time. After graduating from Waseda High School, a preparatory school for the prestigious Waseda University, he enrolled at the university’s Engineering department, from which he graduated in Applied Physics at the top of a class of one hundred. He’s the very model of an honor student. In 1989 he completed his postgraduate studies, only to spurn offers of employment and take vows instead.

He became an important member of the Aum cult’s Chemical Brigade in their Ministry of Science and Technology. Along with fellow perpetrator Masato Yokoyama, Hirose was a key figure in their secret Automatic Light Weapon Development Scheme. A tall, serious-looking youth, he seems rather more boyish than his 32 years. In court he chooses his words carefully and speaks quietly and to the point.

The morning of March 18, Hirose received orders from his Ministry of Science and Technology superior Hideo Murai to plant sarin on the subway. “I was extremely surprised,” he said later in court. “I shuddered to think of all the victims this would sacrifice. On the other hand, I knew I couldn’t be well-versed enough in the teachings to be thinking like that.” In awe of the gravity of his mission, he felt a strong “instinctual resistance,” but his adherence to Aum’s teachings was even stronger. While he now admits his error, he claims he realistically had neither the liberty nor the will to disobey orders from above—that is, as he says himself, from Shoko Asahara.

Hirose was ordered to board the second car of an Ogikubo-bound Marunouchi Line train at Ikebukuro Station. At Ochanomizu Station, he would poke holes in two packets of sarin and be picked up by Kitamura’s car waiting outside. The train number was A777. Detailed instructions were provided by Hirose’s “Big Brother,” Yasuo Hayashi. After twenty days of training at Kamikuishiki Village, Hirose finally poked so hard with his umbrella that he bent the tip.

Leaving the Aum ajid in Shibuya, west central Tokyo, at 6:00 on the morning of March 20, Hirose and Kitamura drove to Yotsuya Station. There Hirose boarded a westbound Marunouchi Line train for Shinjuku, then changed to the Saikyo Line northbound for Ikebukuro. He bought a copy of a sports tabloid at a station kiosk and wrapped the sarin packets in it. He waited around before boarding the appointed Marunouchi Line train, standing by the middle door of the second car. But when it was time to release the sarin, the newspaper wrapping made such a noise it drew the attention of a nearby schoolgirl—or at least Hirose thought it had.

Unable to bear the mounting tension, he got off the train at Myogadani or Korakuen Station and stood on the platform. Overwhelmed by the horror of what he had been commanded to do, he was filled with an intense desire to leave the station without going through with it. He confessed to feeling “envious of the people who could just walk out of there.” In retrospect, that was the crucial moment when things might have been very different. Had he simply left the station, hundreds of people would have been spared a major derailment in their lives …

But Ken’ichi Hirose gritted his teeth and overcame his doubts. “This is nothing less than salvation,” he told himself. The act of doing it is what matters, and besides, it’s not just him, all the others are doing the same thing too. He couldn’t let the others down. Hirose got back on the train, taking another car, the third, to avoid the inquisitive schoolgirl. As the train approached Ochanomizu Station, he pulled the packet of sarin out of his bag and dropped it unobtrusively on the floor. The newspaper wrapper fell off as he did so and the plastic packet was exposed, but by then he didn’t care. He didn’t have time to care. He repeated an Aum mantra under his breath in order to steel himself, then, just as the doors opened at Ochanomizu, he banished all thoughts and stabbed at the bag with the tip of his umbrella.

Before getting into Kitamura’s waiting car, Hirose rinsed the umbrella tip with some bottled water and tossed it into the trunk. Despite being extremely careful in his movements, he soon showed the unique symptoms of sarin poisoning. He couldn’t speak properly and breathing was difficult. His right thigh began to twitch uncontrollably.

Hirose hurriedly injected himself in the thigh with the atropine sulphate given him by Ikuo Hayashi. With his excellent scientific background, Hirose knew how deadly sarin could be, but it was far more toxic than he had expected. The thought crossed his mind: “What if I just die like this?” He remembered Ikuo Hayashi’s advice: “At the first sign of any physical abnormalities, report to Aum Shinrikyo Hospital in Nakano for immediate medical treatment.” Hirose had Kitamura drive the car to Nakano, but was completely caught off-guard to find the doctors there knew nothing about the secret sarin drop. They returned swiftly to the Shibuya ajid, where Ikuo Hayashi administered emergency care.

Back at Kamikuishiki Village, Hirose and Kitamura joined the other perpetrators to deliver to Asahara the message: “Mission accomplished.” Whereupon Asahara commended them, saying, “Trust the Ministry of Science and Technology to get the job done.” When Hirose confessed to having changed to another car because he thought he’d been noticed, Asahara seemed to accept his explanation: “I was following everyone’s astral projections the whole time,” he said, “and I thought Sanjaya’s (Hirose’s cult name) astral projection seemed dark, as though something had happened. So that’s what it was.”

“The teachings tell us that human feelings are the result of seeing things in the wrong way,” said Hirose. “We must overcome our human feelings.” He had succeeded in puncturing two plastic packets, releasing 900 milliliters of liquid sarin onto the floor. As well as the one passenger who died, 358 were seriously injured.

At Nakano-sakaue Station a passenger reported that someone had collapsed. Two severe casualties were carried out: one died; the other, “Shizuko Akashi,”* was temporarily reduced to a vegetative state. Meanwhile, a station attendant, Sumio Nishimura, scooped up the sarin on board and cleared it from the station (see this page). But the train itself continued on its way, the car floor still soaked with liquid sarin.

At 8:38 the train reached Ogikubo, the end of the line. New passengers got on and the train headed back eastward in the opposite direction. Passengers in the eastbound train complained of feeling ill. Several station attendants that had boarded the train at Ogikubo also mopped the floor, but they too gradually became unwell and had to be rushed to the hospital. The train was taken out of service two stops later at Shin-koenji Station.†

“I felt like I was watching a program on TV”

Mitsuo Arima (41)

Mr. Arima lives south of Tokyo in Yokohama. His clean-cut features, smart clothes, and bearing give him a youthful appearance. He defines himself as optimistic and fun-loving; eloquent, but never dogmatic. It’s not until you sit and talk to him that you realize he has one foot in middle age. After all, 40 is a turning point, an age when people begin to ponder the meaning of it all.

Married with two children, Mr. Arima works for a cosmetics company. He and his colleagues play in a band for fun. He plays guitar. Due to commitments at work, Mr. Arima had the bad luck to catch the Marunouchi Line—which he doesn’t usually take—and get gassed.

![]()

Actually, the whole week before I’d been down with the flu. That was the first time in my adult life I’d ever taken to my bed. I’m never ill.

So there I was, going back to work that day after my absence, which is why I wanted to get to the office a little early, to make up for lost time (laughs). I left the house ten minutes earlier than usual.

I always sit down and have a leisurely read of the newspaper on the Yokohama Line going west to the Hachioji office, but that day it just so happens I was supposed to go to the downtown Shinjuku office for a special meeting of regional managers. I planned to spend the morning in Shinjuku, then put in an appearance at Hachioji.

The meeting began at 9:45. I left the house before 7:00, taking the Yokosuka Line up to Shimbashi, then the Ginza Line to Akasakamitsuke, then changed to the Marunouchi Line for Shinjuku-gyoemmae: travel time, an hour and a half. The Marunouchi Line clears out after Akasaka-mitsuke, so I’m assured of a seat. But that day, I sit down and straightaway I notice an acid smell. Okay, trains often smell funny, but this was no ordinary smell, let me tell you. I remember a lady sitting across from me covering her nose with a handkerchief, but otherwise there was nothing obviously wrong. I’m not even sure that smell was sarin. It’s only later I thought back, “Ah, so that’s what it was.”

I got off at Shinjuku-gyoemmae, except it was incredibly dark, like somebody had switched off all the lights. It had been a bright day when I left home, but when I exited above ground everything was dim. I thought the weather had taken a turn for the worse, but I looked up and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. I was taking a hay-fever remedy at the time, so I thought it might be a reaction to the drug; It was different from my usual, so maybe this was a side effect.

But everything was still dark when I reached the office and I felt so lethargic I just sat in a daze at my desk, gazing out of the window. The morning meeting ended and everyone else went out for lunch. But everything was still dark and I had no appetite. I didn’t feel up to talking to anyone. So I ate quietly alone and then I broke out in a sweat. The TV was on in the ramen noodle shop and it’s round-the-clock news about the gas attack. The others tease me, saying, “Hey, maybe you have sarin poisoning,” but I knew it was the hay-fever remedy, so I just laughed along.

The meeting started again in the afternoon, but I’m not at all better. I decided to get examined by a hay-fever specialist. I excused myself from the meeting at 2:00. At that point I was starting to think, “Hey, what if it is sarin?”

For peace of mind, I decided to go to the local doctor near my home, the one who prepared the new hay-fever remedy. It was still a toss-up between hay-fever remedy or sarin poisoning. So I went all the way back to Yokohama, but when he heard I’d been on the subway before I came down with the symptoms he tested my pupils and recommended immediate hospitalization.

He took me by ambulance to Yokohama City College Hospital. I was able to get out of the ambulance and walk by myself, so my symptoms were slight then. But at night the headaches started. Around midnight a huge dull thud of pain. I called over the nurse, and she gave me an injection. The headache wasn’t a sharp shooting pain, it squeezed tight and hard like a vise for a good hour. Maybe this is it, I thought, but soon the pain subsided, and I was thinking, “Yeah, I’ll pull through.”

The eyedrops they’d given me to dilate my pupils worked a bit too well, though, and now my pupils were wide open. The next day when I woke up everything was so bright… so they put up paper all around my bed to block out the glare. Thanks to that it was another day in the hospital before my pupils were normal again.

In the morning my family visited. I was still in no condition to read the newspaper, but I found out how serious the attack was. People died. I might have been killed myself. Oddly enough I didn’t feel any sense of crisis. My reaction was, “Well, I’m okay.” I’d been right at the epicenter, but instead of shuddering at the death toll, I felt like I was watching a program on TV, as if it were somebody else’s problem.

It was only much later that I began to wonder how I could have been so callous. I ought to have been furious, ready to explode. It wasn’t until the autumn that it really sank in, little by little. For instance, if someone had fallen down right in front of me, I like to think I’d have helped. But what if they fell fifty yards away? Would I go out of my way to help? I wonder. I might have seen it as somebody else’s business and walked on by. If I’d gotten involved I’d have been late for work …

Since the war ended, Japan’s economy has grown rapidly to the point where we’ve lost any sense of crisis and material things are all that matters. The idea that it’s wrong to harm others has gradually disappeared. It’s been said before, I know, but this really brought it home to me. What happens if you raise a child with that mentality? Is there any excuse for this kind of thing?

It’s strange, you know, back in the hospital with everyone around me in a blind panic, I didn’t feel in the least horrified. I was so calm and collected. If someone had made a joke about sarin, I wouldn’t have cared in the least. That’s how little it meant to me. That summer I began to forget that there had even been a “Tokyo gas attack.” I’d read something in the newspaper about a lawsuit for damages and I’d think, “Ah yes, that again,” as though it had nothing to do with me.

I’ve worked in Tokyo for twelve years, I know all about its peculiarly settled ways. Ultimately, from now on I think the individual in Japanese society has to become a lot stronger. Even Aum, after bringing together such brilliant minds, what do they do but plunge straight into mass terrorism? That’s just how weak the individual is.

“Looking back, it all started because the bus was two minutes early”

Kenji Ohashi (41)

Mr. Ohashi is married with three children and has worked at a major car dealership for twenty-two years. He is presently Business Department head at their service center in Ohta Ward, southeast Tokyo.

At the time of the Tokyo gas attack, the service center was still unfinished and he was working from a temporary office to the west in Nakano Honancho, Suginami Ward. Mr. Ohashi was exposed to sarin on his commute to this office, while traveling on the Marunouchi Line.

An old hand at the car-repair business, Mr. Ohashi stands in front of the shop and deals directly with the customers. An experienced technician, he is a real working-man, with short hair and a solid build. He’s not the talkative type, and speaks slowly and thoughtfully about the gas attack.

He still suffers from particularly severe aftereffects, but he has also joined a victims’ support group and actively participates in its campaigns. He is trying to organize a self-help network to link all the individual sufferers. The hour and a half he spent talking to me must have given him an excruciating headache. I can only offer my apologies and my sincere thanks for his cooperation.

![]()

When I used to commute to Nakano, I’d go from Koiwa via Japan Railways to Yotsuya Station. From home I’d catch the bus or cycle to Koiwa Station; well, probably more often it was the bus.

On the day of the gas attack I left the house as usual just after 7:00. But as luck would have it, the bus was about two minutes early. It was always late, but for once it was ahead of schedule. I ran for the stop but didn’t make it in time, so I had to catch the next bus at 7:30 instead. By the time I reached Yotsuya I had already missed two trains on the subway. Looking back, it all started because the bus was two minutes early. My timing has never been so bad! Until then I’d traveled back and forth like clockwork.

I always went for the third car from the front on the Marunouchi Line. That way you get the best view from the Yotsuya Station platform. Looking out past the roofline you can see the Sophia University soccer field, it’s like a breath of fresh air! That day, however, the third car was ridiculously empty. It’s never like that. Yotsuya is so crowded, you can never get a seat. You just get on and hope for a seat later. So I knew then something was up.

As soon as I got on, I noticed two people in odd postures behind me. A man hunched over in his seat, nearly falling off, and a huddled woman, head down and sort of curled up. And then there was this really strange smell. At first I thought there must be some drunk making the place stink, like when a drunk throws up. It wasn’t a sharp smell, it was a little sweet, like something rotten. Not like paint thinner, either. We do paint jobs, too, so I know what thinner smells like. It didn’t make your nose sting like that.

Well, I got a seat, so I was prepared to put up with a little smell; and once I’d sat down I soon closed my eyes and fell asleep. I usually read a book on the train, but it was Monday and I was sleepy. Still, I didn’t fall asleep, really, just closed my eyes and half-dozed. Sounds still reached me, so when I suddenly heard the announcement, “This station is Nakano-sakaue,” I snapped awake, like a reflex action, jumped up, and left the train.

Everything was dim. The lights on the platform were faint. My throat was parched and I was coughing; a really bad, chesty cough. There’s a water cooler by a bench at the end of the station, so I thought I’d better go and rinse my mouth. That’s when I heard the shouting: “Someone’s fainted!” It was this tall young salaryman. When I looked back inside, I saw the man in the car had fallen right over, parallel to the seats.

But I didn’t feel too good myself. I went to the water cooler and gargled. My nose was running and my legs were shaky. It was hard to breathe. I just plunked myself down on a bench. Then, maybe five minutes later, they carried out on a stretcher the man who’d fainted, and the train started off again.

I didn’t have the foggiest idea what had hit me. Only everything had gone dark before my eyes. My lungs were wheezing like I was running a marathon and the whole lower half of my body was cold and trembling.

Altogether maybe five or six passengers were brought up to the station office. Two of them on stretchers. But the station attendants hadn’t a clue either. They were asking us what had happened. The police arrived about half an hour later, and predictably started questioning us. It was really painful, but I made the effort to spell things out as best I could. Someone had fainted and I was afraid if I lost consciousness I’d be done for. That’s why they were trying to keep us talking, I thought, so I forced myself to speak.

Meanwhile, during alf this, the station attendants themselves began to feel sick. Their sight was going. We’d been in that office for at least forty minutes, everyone breathing the same air. We probably should have gone above ground earlier.

So we went upstairs. The fire department had set up a temporary relief shelter in an alleyway. “Just sit here for now,” they told us. But it was so, so cold, I couldn’t stay sitting there, just a thin plastic sheet on the ground. Lie down and you’d freeze. It was still March, after all. There was a bicycle parked there, so I propped myself against that. “Mustn’t pass out,” was all I could think. Two people did lie down, but the rest did like me. I tell you, it was damn cold. We were forty minutes in the station office and twenty minutes out there. A whole hour had gone by and none of us had received any treatment.

We couldn’t all go in the ambulance, so I was taken by police van to Nakano General Hospital. There they laid me out on a bench while they examined me. The results weren’t good, so they put me on intravenous straightaway. I’d heard reports in the police van over the radio about the effects of poisoning and so on. That’s when I realized I’d been poisoned.

At this point, apparently, they knew it was sarin at Nakano General, but there we were still wearing our sarin-saturated clothes. Soon the hospital staff were complaining of eye trouble too. All through the morning my body was like ice. Even with an electric blanket, I was shivering. My blood pressure was up to 180. Ordinarily I run in the 150s tops. Still, I wasn’t worried, just puzzled.

I was in the hospital for twelve days: vicious headaches the whole time. No painkiller worked. I was in agony. The headaches would come in waves all day, receding then getting stronger. I also ran a high fever for two days; as high as 40° C [104° F].

I had cramps in my legs and trouble breathing for the first three or four days. It was like there was something stuck in my throat. Excruciating. My eyes were so bad I’d look outside and see no light at all. Everything was a blur.

They kept me on intravenous for five days. On the fifth day, my Cholinesterase level had returned to near normal, so they detached the drip.* My pupils slowly recovered, but whenever I focused on anything I felt a sharp shooting pain at the back of my eyes, like I was being stabbed with a pick.

They finally discharged me on March 3 and I took a month off work to recuperate at home. I still suffered from splitting headaches. And with my legs so wobbly, I was bound to fall arid hurt myself while commuting—what they call “secondary injury.”

First thing in the morning my head would hurt. It was like a killer hangover. My head throbbed with each pulse, every heartbeat, and it kept up relentlessly. Still, I didn’t take any medicine. I simply buckled down and took the pain. Having absorbed sarin, the risk of taking the wrong medicine was worse than taking nothing, so I avoided all headache remedies.

I took off all of April, then put in an appearance at our newly constructed Showajima Center after the early May holidays, and started back on the job. We were arranging desks, connecting computers, straight through every day until late at night. I know I overdid it. My head still hurt. It got worse when the June rains set in. Every day it felt like I had some massive weight crushing my skull. And I still got shooting pains when I tried to look at anything.

I was afraid to commute again. I’d board the train and see the door slide shut before my eyes, and in that very instant my head would seethe with pain. I’d get off and go through the ticket barrier, thinking, “I’m okay,” and the weight would still be there in my head, bearing down. I couldn’t concentrate on anything. If I talked for more than an hour my head would be killing me. It’s still that way now. In mid-April when I filed a police report, the effort wore me out.

Then, after a week’s vacation in August, I felt a noticeable change. I was fine on the train. My headaches weren’t so bad. Maybe the time away from work eased the tension. The first few days back at work were great, but a week later I was back to square one. Headaches again.

One day in August it took me three hours to get to work. I had to stop off all along the route and rest until the pain subsided; but the moment I was back on board a train it would flare up again, so I’d have to rest—over and over again. It was 10:30 by the time I reached the office!

I went to see a psychologist, Dr. Nakano, at St. Luke’s Hospital. I related my case history and symptoms up to that point, and he said, “Absolutely hopeless! It’s suicidal the way you’re working!” He didn’t mince his words. After that I went to him twice a week for counseling. I took tranquilizers, sleeping pills—finally I could sleep at night.

I ended up taking another three months off work, all the time keeping up the counseling and the medicine. You see, I had what’s called posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]. Examples range from returning Vietnam War veterans to victims of the Kobe earthquake. It comes from severe shock. In my case, for four months after the gas attack, I’d pressured myself into working all hours, overtaxing my body, which piled on the stress even more. It was only thanks to my summer vacation that the tension snapped.

A complete cure of PTSD is apparently very rare. Unless you clear away all those memories, the psychological scars remain. But memories aren’t so easily erased. All you can do is try to reduce stress and not overwork.

Commuting is still hard. One hour on the train from Koiwa, then change at Hamamatsucho to the monorail, gradually my head gets weighed down. Okay, I’m sure I look all right, but then no one understands this pain, which makes it doubly hard for me at work. My boss is decent enough, though, he sympathizes: “If I’d caught a different train,” he says, “it could’ve been me.”

For a while after the gas attack, when I was sleeping at the hospital, I had terrible nightmares. The one I remember best was a dream in which someone pulled me out of my bed next to the window and dragged me around the room. Or I turned and suddenly saw someone standing there who’s supposed to be dead. Yeah, I often met dead people in my dreams.

I used to have dreams in which I was a bird flying in the sky, but then I’d get shot down. An arrow or a bullet, I don’t know. I’m lying there wounded on the ground and I get trampled to death—dreams like that. Happy at first, flying through the sky, then a nightmare.

About the criminals themselves, what I feel goes beyond hatred or anger. Anger is too easy. I just want them dealt with as soon as possible—that’s all I have to say.

I interviewed Mr. Ohashi in early January 1996, but met him again at the end of October. I was curious what progress he’d made. He was still plagued by headaches and a feeling of lethargy.

At the same time, his most immediate problem is that he has been relieved of most of the work he used to do at his company. The week before this second interview, his boss had called him into his office and said, “For the time being, why don’t you take it a little easier and do work that doesn’t require such intense detail, so that you can get better?” After discussions, it was decided that the senior department head should take over Mr. Ohashi’s duties as Business Department line director.

Nevertheless, Mr. Ohashi’s complexion looked much healthier. He now travels from his house in Edogawa Ward to Dr. Nakano’s clinic in central Tokyo by motorcycle (trains still give him headaches). He came to the interview by bike. He seemed more youthful and full of life than before. He was even smiling. But as he himself says, pain is invisible, and known only to the sufferer.

Since February I’ve been getting into the office by 8:30, coming home around 3:00. I have headaches all day. They come in waves, mounting and receding. It hurts right now and will no doubt last a long time. It feels like a heavy weight bearing down, covering my head, like a mild hangover, all day, every day.

For a week or two in late August to early September, the pain was especially bad. I just got by with headache tablets and ice packs. My boss told me to just work mornings and go home, but the headaches haven’t gotten any better. It’s chronic, but I’m used to it. It’s over here on the left now, but other days it comes on the right or all over …

This year I’ve been getting a processing system up and running for making car-repair estimates based on my twenty years’ experience. If only the computer screen were monochrome green—I find that three or four colors make my eyes hurt. Focusing is also difficult. If I’m looking one way and someone calls me and I turn around suddenly, it hits me like a sledgehammer. This happens all the time—a shooting pain in the back of my eyes. As if I were being skewered. When it’s very bad there have been times I’ve contemplated suicide. I almost think I’d be better off dead.

I’ve been to eye specialists, but they can’t find anything wrong. Only one doctor told me, “Farmers sometimes get this, too.” Apparently mixing up organic fertilizers damages their nerves, causing the same symptoms.

But here it is the end of summer, and my head is still killing me. The company still lets me go into work, but I’ve been relieved of my managerial responsibilities. My boss says that a high-stress workplace would be bad for me physically, but the result of this special treatment is that it’s extremely hard for me to perform like a businessman in his prime. I’m grateful they want me to take it easy, and after the gas attack I did work harder than usual. Not wanting to inconvenience the company, I kept my headaches a secret and, well, overworked, but I’m not the type of person who can just sit idly by.

To be honest, my present position leaves me twiddling my thumbs. They even moved my desk. I go to the office and there’s nothing much for me to do. I’ll sit by myself and tally up slips, work that anyone could do. But having gained all this experience up to now, I can’t very well not work.

Sometimes I think up different proposals on my own, regardless of whether they’ll work or not. Realistically, though, not knowing if this pain will ever go away completely, or how long I’ll have to keep living like this, I can’t see any future. I’m working now from morning until noon and then I’m exhausted.

Because of my accident benefits, they’ve had to cut my bonus to 2.5 million yen a year, which is quite a squeeze financially. Bonuses are really important to a salaryman. They barely make up for the month-to-month shortcomings. I just had a new house built and there’s a thirty-year loan to pay back. I’ll be 70 then.

I know I don’t appear to be in constant pain, but imagine wearing a heavy stone helmet, day in, day out… I doubt it makes much sense to anyone else. I feel very isolated. If I’d lost an arm, or was reduced to a vegetable, people could probably sympathize more. If only I’d died then, how much easier it would have been. None of this nonsense. But when I think of my family, I have to go on …

“That day and that day only I took the first door”

Soichi Inagawa (64)

Mr. Inagawa’s gray hair is thinning slightly but combed neatly in place. His cheeks are red, though he’s not especially plump. More than ten years ago he became diabetic and has been watching his diet ever since. Yet he still has his drinking companions and is especially fond of sake.

He wears a well-pressed charcoal gray three-piece suit and speaks clearly and succinctly. You can tell he prides himself on his working life up to now, having worked throughout Japan’s postwar decades.

He was born in Kofu, a provincial city in the mountains, two hours west of Tokyo. After graduating from a vocational high school for electricians, he joined a Tokyo construction company in 1949. In time he moved from the construction site to an office and, at 60, he retired as Business Division director. He had other job offers, but “all of a sudden I got fed up with bosses.” He and two friends his age decided to set up their own business dealing in lighting equipment. The office is located directly above Shin-nakano Station.

Business is steady though not especially busy, “But it still feels great not having to answer to anyone else.” He and his wife live in Ichikawa, across Tokyo Bay to the east in Chiba Prefecture. Their two children have left home and they have three grandchildren, the youngest born a month after the gas attack.

He always carries two lucky charms his wife gave him—not that he really believes in that sort of thing …

![]()

I leave the house at 7:25 and get to work by 8:40. Office hours are supposed to start at 9:00, but since it is my company I’m not so strict about it.

On March 20 I got a seat from Ochanomizu. I changed at Shinjuku to the Marunouchi Line, and again I managed to get a seat. I always travel in the third car from the front.

That day I sat in the first seat of the third car. Then I saw a puddle in the area between the rows of seats. This big pool was spreading, as if a liquid had leaked out. It was the color of beer and smelled funny. In fact it stank, which is why I noticed it.

That day the train was surprisingly empty. Not a soul standing, and only a few people sitting. Thinking back on it now, that strange smell had probably kept them away.

One thing bothered me: a man sitting alone right next to the puddle. I thought he was sleeping when I got on, but gradually his posture was slipping in a very odd way. “Strange, is he ill or what?” Then, just before Nakano-sakaue, I heard a thud. I was reading my book, but I looked up and saw the man had fallen right out of his seat and was lying on the floor faceup.

“This is terrible,” I thought, trying to size up the situation. The train was almost at the station. As soon as the door opened a crack, I jumped out. I wanted to fetch help, when a young man ran past me to the front of the platform and summoned a station attendant.

There was a woman sitting across from the man who fell over and she was apparently flat out too. She was somewhere around 40 or 50. I’m really bad with women’s ages. Anyway, a middle-aged woman. The man was fairly elderly. The station attendant managed to drag the man off the train, then another came running, lifted up the woman, and carried her out, saying, “Are you all right?” I just stood watching on the platform.

While all this was happening, a station attendant had picked up a bag of liquid and brought it out onto the platform. No one had any idea it was sarin, it was just something suspicious to be disposed of. Then I got back on the train and it moved off again. I moved to the next car down, as I didn’t want to be where the strange smell was. I got off at the next station, Shin-nakano.

But then as I was walking along the underground passageway, I started sniffling. “Odd,” I thought, “am I coming down with a cold?” The next thing I knew I was sneezing and coughing, then things started to go dim in front of my eyes. It happened almost simultaneously. “This is most odd,” I thought, because I still felt perfectly all right. I was bright and aware. I could still walk.

I went straight to my office, which is right above the station, but my eyes were still dim, nose running and coughing like crazy. I told them, “I’m not feeling so well. Think I’ll lie down for a bit,” and stretched out on the sofa, cold towel over my eyes. A colleague of mine said a hot towel would be better, so next I tried a hot towel, and lay there for an hour, warming my eyes. And what do you know? My eyes were as good as new. I could see the blue sky again. Up until then it had been as black as night, nothing had any color.

I worked as though nothing had happened, then around 10:00 a call came from my wife saying, “There’s been big trouble in the subway, are you all right?” Not wanting to worry her, I said, “Fine. Couldn’t be better.” Well, at least my eyes were fine.

At lunch I happened to see the TV at a soba noodle shop. What a commotion! I’d heard sirens nearby that morning, but I hadn’t paid them any attention. The TV mentioned that the victim’s vision goes dark, and that struck a note, but I still didn’t connect my dimmed vision with those strange-smelling packets.

I went to Nakano General Hospital to have my eyes tested. As soon as they saw my contracted pupils they shot me up with an antidote and put me on an IV. Blood tests showed my Cholinesterase level was way down. They hospitalized me straightaway, and I wasn’t to be released until my Cholinesterase was back to normal.

I phoned the office to tell them: “It’s like this and I have to be hospitalized for I don’t know how many days. Sorry to trouble you, but could you tidy up my desk?” I called home too, and my wife lays into me, saying, “What was all that about being perfectly fine?” (laughs)

I was in the hospital six days and felt hardly any pain all that time. The sarin had been right there next to me, yet my symptoms were miraculously light. I must have been upwind of it. Air flows through a train car from front to back, so I’d have been in a real fix if I’d sat at the back, even if only for a few stops. I suppose that’s what you call Fate.

Afterward I wasn’t scared to travel on the subway. No bad dreams either. Maybe I’m just dull-witted and thick-skinned. But I do feel it was Fate. Usually I don’t go in through the first door nearest the front. I always use the second, which would have put me downwind of the sarin. But that day and that day only I took the first door, for no special reason. Pure chance. In my life up to now I never once felt blessed by the hand of Fate—nor cursed either, just nothing at all. I’ve had a pretty dull, ordinary sort of life … then something like this comes along.

“If I hadn’t been there, somebody else would have picked up the packets”

Sumio Nishimura (46)

Mr. Nishimura is a Subway Authority employee working at Nakano-sakaue Station. His title is Transport Assistant. On the day of the gas attack, he removed the packets of sarin from the Marunouchi Line train.

Mr. Nishimura lives in Saitama Prefecture. He got his job with the subway through the intervention of a friend. Railroad jobs were said to be “solid” work, much respected in the countryside, so he was overjoyed when he passed his employment exam in 1967.

Of average height, he’s a little on the skinny side. Yet his complexion is good, his eyes steady and attentive. If I found myself sitting next to him at a bar, I probably wouldn’t guess his profession. Not an office job—that much is apparent—he’s worked his way up on-site, a self-made man. A closer look at his face would reveal that his job involved a fair amount of daily stress. So a bottle of sake with his friends after work is a real pleasure to him.

Mr. Nishimura kindly agreed to tell his story, even though it was obvious he didn’t really want to talk, about the gas attack. Or, as he said, he’d “rather not touch it.” It was a terrible event for him, of course, a nightmare he’d rather forget.

This was true not only for Mr. Nishimura, but probably for all the subway staff. Keeping Tokyo’s underground train system running on time without hitches or accidents is their prime objective every minute of the day. They don’t want to recall the day when it all went horribly wrong. This made it all the more difficult to get any kind of statement from the subway staff. At the same time they don’t want the gas attack to be forgotten or their colleagues to have died in vain. My deepest thanks go to him for his cooperation in contributing this invaluable testimony.

![]()

At the subway we have a three-way rotation: day shift, round-the-clock duty, and days off. Round-the-clock is a twenty-four-hour shift from 8:00 in the morning to 8:00 the following morning. Naturally no one is expected to stay up all the way through. We have rest intervals in the bunk room. After that we get a day off, then go back to day-shift duty. Each week has two round-the-clocks and two days off.

With round-the-clock duty we can’t just leave in the morning. The rush hour peaks between 8:00 and 9:30, so we do overtime. That March 20 was the morning after my round-the-clock duty and I was on “rush-hour standby.” That’s when the gas attack happened.

The day fell between holidays, a Monday; the same number of passengers as usual. Ogikubo-bound Marunouchi Line trains all suddenly empty out after passing Kasumigaseki. From Ikebukuro to Kasumigsaseki passengers keep boarding thick and fast, but after that it’s just people getting off and no one getting on.

Rush-hour standby involves overseeing the train crew’s operations, checking that there are no irregularities, seeing that the crew change goes smoothly, that the train isn’t late; supervising, really.

Train A777 arrived on time at Nakano-sakaue at 8:26. When it pulled in, a passenger called over a station attendant, who then shouted across to an attendant over on the Ikebukuro platform, “Get over here quick, there’s something wrong!”

I was about fifty yards away on the same platform and couldn’t quite catch what he said, but it seemed something was up, so I hurried on over. Even if an irregularity’s reported, the other attendant has the tracks in between and can’t just hop over. That’s why I went. I entered the third car from the front through the farthest back of the three doors and saw a sixty-five-year-old man sprawled on the floor. Opposite him, a fifty-year-old woman had slid off her seat. They were panting, gasping, bloodstained pink foam coming out of their mouths. The man seemed totally unconscious at first glance. The thought flashed through my mind: “Ah, a double love suicide.” But of course they weren’t; it was just a fleeting impression. The man died later. The woman, I hear, is still in a coma.

There were only those two in the car. No one else. The man on the floor, the woman on the seat opposite, and two packets in front of the nearest door. I spotted them the minute I got inside. Plastic pouches about thirty centimeters square, with liquid inside. One was puffed up, the other had collapsed. And this sticky-looking liquid had flowed out.

There was a smell, but I really can’t begin to describe it. At first I told everyone it was like paint thinner, but actually it was more like a burnt smell. Oh, well, no matter how many times they ask me, I never know what to say. It just stank.

Soon other station attendants came running and we carried out the fallen passengers. We have only one stretcher, so we carried the man out first, then locked hands under the woman and set her down on the platform. Neither the driver nor the conductor on the train had any idea this situation had arisen.

So we helped the two passengers off and signaled that the train was ready to leave. “Take her out,” just to move it on. You can’t let a train sit still for long. There was no time to wipe the floor. But there’s that strange smell, the floor’s wet, so we had to get them to clean it up in Ogikubo at the end of the line. I rang Ogikubo Station, saying, “777 car number 3’s floor needs cleaning, can you take care of it?” But gradually everyone is starting to feel ill, both attendants and passengers. This was about 8:40.

It’s five stops from Nakano-sakaue to Ogikubo. The train takes twelve minutes. Train 777 was a switchback, numbered 877 on the return. But the passengers who boarded the 877 at Ogikubo were feeling funny too. They were mopping the car floor at Ogikubo—I think they were still cleaning it while the train was heading back this way—and what happens? Everyone who is cleaning starts to feel sick too. Likewise the passengers riding from Ogikubo to Shin-koenji. Word came down, “There’s something wrong with that train.”

Let’s see, this time I think quite a lot of passengers got on at Ogikubo. The seats are generally all taken, some people standing. We knew we had to check the train this time, so we were waiting for 877 to reach Nakano-sakaue, scheduled for 8:53. But they took it out of service at Shin-koenji.

Well, after we carried out the two passengers, I picked up the plastic sarin packets with my fingers and put them on the platform. They were the sort of square, plastic packs they use for intravenous drips. I was wearing white nylon gloves, like we always wear on patrol duty. I tried to avoid touching the wet parts.

I assumed the man and woman had used these to commit suicide, so I thought, “These are dangerous objects, better report them to the police.” I saw a newspaper tucked up on a shelf above the seats, so I grabbed that and placed the sarin packets on top, then lifted the whole thing out onto the platform. Set it down by a column on the platform. Then an attendant came out with a white plastic bag like you get at the supermarket. We dumped the sarin packets in that and tied up the bag. The attendant carried it to the station office and left it there. I didn’t realize, but he apparently put it in a bucket near the door.

Soon passengers were complaining of feeling poorly, so we took them to the office; and not only them, but now many of the station staff were ill. The police and fire department showed up to ask about the circumstances, and they soon realized something strange was going on. At that point we took the bag outside. The police disposed of it somewhere, if memory serves.

When I went to the office to phone, I didn’t actually realize it yet, but my nose was running and my eyes were acting funny. They didn’t hurt, they were just blurred and tingled. I couldn’t see very well. If I tried to focus, then they hurt like mad. It felt fine looking around in a fog, but focus on anything and it hurt. After a while the fluorescent lights and everything began to flare.

Around 8:55 I began to feel dizzy from the glare and it was about 9:00 when I went to the bathroom to wash my face, then lay down in a bunk room for a while. Because the outbreak on the Hibiya Line was earlier, it was about this time that we learned of other problems elsewhere, as well. By now everyone was panicking. It was getting full coverage on TV.

I was feeling ill, so I left the station. Ambulances were racing around the Nakano-sakaue intersection, having a devil of time rounding up all the patients to ferry them away. It was difficult finding an ambulance to take me. They were even using Special Mobile Task Force police vans for ambulances. You know, the ones with the wire screens. They took me in one of those. It was around 9:30 when I reached the hospital. Six of the Nakano-sakaue staff were taken to the hospital and two hospitalized, myself included.

At Nakano General Hospital they already knew that sarin was probably the cause, and they treated me for that: washed my eyes, gave me an immediate transfusion. I had to write my name and address in the register, but I couldn’t see to write, so I scribbled as best I could out of focus.

I ended up six days in the hospital. March 20 was pretty grueling. I was tired out, with only the clothes I was wearing, and all the tests for this and that. My blood Cholinesterase was abnormally low. It took three to four months of continual blood transfusions to bring it back to normal, and until then my irises wouldn’t open properly. Contracted pupils, a lot worse in my case than others. My pupils remained contracted until my discharge. I’d look at a light and wince at the glare.

My wife came racing over to the hospital, but to be frank, I wasn’t in any real life-or-death condition. No very severe symptoms or anything. I hadn’t passed out. Only my eyes hurt and my nose ran.

Rough nights at the hospital, though. Lying there, my whole body felt cold as ice. I have no idea whether it was a dream or reality, but anyway it was vivid enough. It occured to me to push the call button for the nurse, but I just couldn’t press the thing. I was in pain, groaning. That happened twice. Waking up with a start, trying to press the button, and failing.

Considering I lifted the packets of sarin by hand, I’m lucky to get away with such minor symptoms. Or perhaps it had something to do with the direction of the wind in the tunnel. Probably it was all to do with the way I picked them up so that I didn’t inhale the fumes directly, because there were others who picked up the stuff the same way at other stations and died. I’m a heavy drinker, and some of the guys at the office say that’s what saved me. That it was harder for me to become intoxicated. Well, maybe.

It never really hit me that I might have died there and then. I slept days, couldn’t watch TV. Nights I was bored silly with nothing to do, but luckily the physical pain went away early on, so I wasn’t depressed or anything. On March 25 I was discharged, then I rested at home until April 1; after that I went back on the job. I got bored hanging around at home, so I thought it was about time to get out and work.

To tell the truth, I didn’t feel any anger toward the Aum perpetrators at first. When you’re on the receiving end it doesn’t much matter who did it. If someone hits you, you know how to respond. But, of course, as more things have come to light I’ve been outraged. To launch an indiscriminate attack on defenseless people, it’s unforgivable. Because of them, two of my colleagues lost their lives. If the criminals were brought in front of me, I don’t know if I could stop myself beating them to a pulp. I think the criminals should get the death penalty, sure. There are those who argue for the abolition of the death penalty, but after all they did, well, how can they go pardoned?

As for picking up the sarin packets, I just happened to be there at the time. If I hadn’t been there, somebody else would have picked up the packets. Work means you fulfill your duties. You can’t look the other way.

“I was in pain, yet I still bought my milk as usual”

Koichi Sakata (50)

Mr. Sakata was born in Shinkyo (present-day Changchun) in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, but now lives in Futamatagawa, southwest of Tokyo. He, his wife, and his mother live in a bright, tastefully renovated house.

A full-time accountant, Mr. Sakata is exceedingly meticulous about filing his papers. Any question I asked would summon a related clipping, receipt, or memo from a folder without the least searching or shuffling. If he kept his home so orderly, I could just imagine his desk at work.

He enjoys a game of go, and he’s a keen golfer—though he’s so busy at work he makes it to the course maybe only five times a year. He’s in good shape and has never once been ill—until he was hospitalized with sarin poisoning.

![]()

I’ve worked eleven years for—Oil. We’re tarmac specialists. In my last company we had problems with the management. They rubbed everyone the wrong way, so we all bailed out together: “One—two—three—jump!” And we built up this company from scratch.

Am I busy? Not as much as before during the “Bubble.” Now, the property market’s in a downturn. Then there was the deregulation of the petroleum industry. Our suppliers can now access cheaper oil coming in from overseas and we have to start thinking about restructuring.

I leave the house at 7:00 and dash to the station about a mile away in twenty minutes. For exercise, you understand. My blood sugar’s been high lately, so I thought the walk would do me good. From Futamatagawa it’s the Sotetsu Line to Yokohama, then the Yokosuka Line to Tokyo, and from there I take the Marunouchi Line to Shinjuku-sanchome. The commute takes about an hour and a half. I always find a seat from Ginza or Kasumigaseki, so it’s no strain.

On the day of the gas attack my wife had gone back to her family’s house. Her father had died. I think it was the hundredth-day observances over his ashes. So she wasn’t home. I left as usual and changed to the Marunouchi Line at Tokyo Station. I boarded the third car from the front, the one I always travel in when I have to buy milk.

That’s right, when I buy milk I always get off at Shinjuku-gyoemmae. I drink milk at lunch, and every other day I buy two days’ worth on my way in in the morning at a nearby store. If I don’t buy any, I get off at Shinjuku-sanchome. My office is located between Shinjuku-gyoemmae and Shinjuku-sanchome. That day was my milk day, thanks to which, I got caught up in this sarin business. Just my luck.

That day I got a seat at Tokyo Station. If you read the written summary, the perpetrator, Hirose, first boarded the second car, then got off halfway and switched to the third car. He punctured the sarin packets at Ochanomizu, so they were right where I was sitting, by the middle door of the third car. I was too wrapped up in reading Diamond Weekly to notice anything. The detective grilled me later: How could I not notice? But, well, I didn’t. I felt like I was a suspect or something—not nice, let me tell you.

Soon though, I began to feel funny. It was around Yotsuya Station I first felt sick. My nose ran all of a sudden. I thought I’d caught a cold, because I started to feel empty-headed, too, and everything before my eyes grew dark, like I had sunglasses on.

At the time I was scared it was some kind of brain hemorrhage. I’d never experienced anything like it before, so I naturally thought the worst. This wasn’t just a cold; it was a lot more serious. I felt as though I might keel over any minute.

I don’t remember much about the others in the car. I was too concerned about myself. Anyway, somehow I made it to Shinjuku-gyoemmae and got off. I was dizzy; everything was black. “I’m done for,” I thought. Walking was a terrific struggle. I had to grope my way up the steps to the exit. Outside it might as well have been nighttime. I was in pain, yet I still bought my milk as usual. Strange, isn’t it? I went into the AM/PM store and bought some milk. It didn’t even occur to me not to. Thinking back on it now, it’s a mystery to me why I’d buy milk like that when I was in such agony.

I went to the office and stretched out on the sofa in the reception area. But I didn’t feel the least bit better, and one of the women employees said I ought to go to the hospital, so around 9:00 I went to Shinjuku Hospital close by. While I was waiting, a salaryman came in saying, “I started feeling out of sorts on the subway,” and I thought, “I must have the same thing too.” A brain hemorrhage.

I was in the hospital for five days. I thought I was well enough to leave earlier, but my Cholinesterase level still wasn’t up to it. “Get good and well,” the doctor told me. Even so I left early. I pleaded with them, I had a wedding to go to on Saturday. It still took me two weeks for my vision to improve. Even now my eyesight’s bad. I drive, but at night the characters on the signs are hard to read. I had new glasses made, stronger ones. Recently I went to a meeting of victims and this lawyer said, “Everyone whose eyesight is worse, raise your hands,” and there were plenty of people. So it must be the sarin.

Also, my memory’s a lot worse. People’s names just don’t come. I deal with bank employees, right? I always carry a memo in my pocket: who’s the director of which branch … Used to be that sort of thing would simply pop into my mind. Also I’m a go enthusiast, and used to play a game in the office at lunchtime. But now I can barely concentrate. It’s worrying, I tell you. And this is only the first year—what’s going to happen after two or three years? Is it going to stay like this, or is it going to get progressively worse?

I don’t feel especially angry toward the individual culprits. It seems to me they were used by their organization. I see Asahara’s face on television and for some reason I’m not filled with animosity. Instead I wish they’d do more to help the really badly affected victims.

“The night before the gas attack, the family was saying over dinner, ‘My, how lucky we are”

“Tatsuo Akashi” (now 37)

elder brother of critically injured “Shizuko Akashi”

Ms. Shizuko Akashi suffered serious injuries traveling on the Marunouchi Line. She was temporarily reduced to a vegetative condition and at present remains in hospital care. Her brother, Tatsuo, works at a car dealership in Itabashi, north Tokyo. He is married with two children.

After his sister’s collapse, he and his elderly parents took it in turn to visit Shizuko in the hospital. He saw to Shizuko’s every need, with admirable devotion. As head of the family, his outrage toward this senseless crime is beyond words. You can sense it in your skin just talking to him. Behind his peaceful smile and softly spoken voice there is a reserve of bitterness and stubborn determination.

What had his earnest, gentle, devoted sister—who asked nothing more than a little corner of happiness—ever done to be struck down by those people? Until the day that Shizuko can walk out of the hospital on her own feet, Tatsuo will no doubt keep asking himself this difficult question.

![]()

We’re the only two siblings, born four years apart. My own two kids are also four years apart and my mother says they act just like we did. Which I suppose means we fought a lot (laughs), though I don’t remember fighting much. Maybe over little things—what TV channel to watch, who got the last piece of cake … But my mother says whenever Shizuko got candy or something to eat, she would always be sure to say, “Give some to big brother, too.” But then, come to mention it, so does my little girl.

Shizuko was always a helpful soul. At kindergarten or school, if some other kid was crying, she’d always go and ask, “What’s the matter?” And she was painstaking by nature. She kept a diary up until junior high school. Never missed a day’s entry. She filled three whole notebooks.

When she finished junior high, she decided not to go to high school and went to a dressmaking academy instead. Our parents were getting old, she said, so rather than studying any longer, she wanted to find work quickly and lighten their load. When I heard that I remember thinking, “You’ve got more moral strength than me.” She was a serious child. Or rather, she always seemed to think things through to the end. She could never just rush something through and be done with it.

So she went to a dressmaking academy, then got a job sewing, but unfortunately the company was mismanaged and went under. That was after three or four years. She looked around for another job where she could continue to use her seamstress skills, but nothing came up. So she went to work at a supermarket. She was kind of disappointed, but she wasn’t the sort to take off on her own and leave her parents in the lurch, and that was the only job she could find nearby.

She worked there for ten years. She took the bus to the supermarket and worked checkout mostly. Ten years on the job, she became a kind of veteran. Even now, after two years in the hospital, she’s still officially listed as a full employee. And the supermarket’s been a great help since the attack too.

Actually, on that day, she was supposed to attend an employeetraining seminar over in Suginami [west Tokyo]. In April, the new trainees would be coming and Shizuko was down to help instruct them. She’d gone to the seminar the previous year, too, and apparently her boss had asked her to go again.

The day before the gas attack—Sunday, March 19—we’d gone to buy a backpack for my son, who was going to be entering grade school. My wife and I, my parents, and the kids all went out shopping together. Just after noon we all dropped by the supermarket to take Shizuko out to lunch at a nearby noodle shop. Supermarkets are always busy on Sundays and she can’t usually take time off, but somehow that day she got free and we all ate out together.

That’s when she mentioned, “Tomorrow there’s this thing in Suginami I have to go to.” So I said, “Okay, I’ll drop you off at the station.” I had to take the kids to nursery school, then drive my wife to the station anyway. After that I’d park the car and take the train. All I had to do was give her a lift together with my wife. But she said, “It’s too much trouble for you. I’ll just take the local line to the Saikyo Line, then change to the Marunouchi Line.” And I said, “That’ll take forever. You’d be better off going straight to Kasumigaseki, then change to the Marunouchi Line.” Looking back on it now, if I hadn’t suggested that to Shizuko, she would probably never have suffered like this.

Shizuko liked going places. She had one really close friend from school, and the two of them would go on vacation together. But a supermarket’s not like a normal company; you don’t get three or four days off in a row. So she had to pick a quiet time and get someone to fill in for her before she could get away.

Another thing, she loved going to Tokyo Disneyland. She went there a few times with her best friend, and whenever she managed to get a Sunday off she would invite us all: “C’mon, let’s go!” We still have our snapshots of those times. Shizuko only liked the thrill rides: roller coasters and that sort of thing. My wife and our eldest, that’s what they like, too. Not me, though. So while the three of them went on one of those scary rides, I’d sit with my younger daughter on the merry-go-round and wait for them. Like, “You all just go have fun. I’ll wait right here.” Yeah, come to think of it, the place we went to most often as a family was Disneyland.

Whenever there was a special occasion, Shizuko would always buy some kind of present. Like our parents’ birthdays or the kids’, our wedding anniversary. She kept all those dates in her head. She remembered everyone’s favorite things. She never touched a drop of alcohol, but since our parents drink, she’d study which brands were supposed to be good and come by with a bottle. She was always so exacting, so attentive to those around her. For instance, if she went on vacation somewhere, she’d be sure to bring home souvenirs or buy cookies for her colleagues at work.

She’d fret so much over personal relationships at work. She’s such an earnest soul; the least little problem she’d take so much to heart. Some throwaway remark would niggle at her, things like that.

Shizuko never married, in part because she felt so responsible toward our parents. There’d been matchmaking attempts, but either the man lived too far away or she didn’t want to leave our parents behind, so in the end nothing came of it. I’d gotten married and left home, so I suppose she had a duty to look after our parents. By then Mother’s knees had given out and she had to walk with a stick … which is what gave Shizuko such a strong sense of duty. Much stronger than mine.

Yeah, and Father’s business had folded, which left him without work, so I suppose she decided to take up the extra financial burden. Shizuko was a hard worker. She’d say, “I don’t need time off,” and force herself to go to work.

On March 20 I passed by the old house and picked up Shizuko, then dropped her and my wife off at the station. That must have been around 7:15. Then I took the kids to nursery school just before 7:30, and walked to the station.

If Shizuko and my wife caught the 7:20, that would put her into Kasumigaseki just before 8:00, and it’s a long walk between the Chiyoda Line and the Marunouchi Line, so that meant she got on the train with the sarin. And to make matters worse, she probably boarded the very car where the sarin packet was. Just once a year she took the Marunouchi Line to go to a training seminar.

She collapsed at Nakano-sakaue Station and was taken to the hospital. I heard that the station assistant who tried to give her mouth-to-mouth inhaled sarin himself and collapsed in the process. I didn’t meet him, though, so I don’t really know.

I learned about the gas attack through Head Office. It’s on the Hibiya Line and several employees had been affected, so they called to ask if everything was all right at our end. I turned on the TV to find out what was going on and I’ve never seen such an uproar.

I phoned my wife straightaway, but she was okay. Then I called my mother, because if there’d been any trouble Shizuko would have called her. But there’d been no message. “She must be all right, then,” I thought. “She’s probably sitting in that seminar right now.” Still, it made me uncomfortable not being able to get in touch with “To be perfectly frank,” the doctor told me, “tonight is very critical. She’s under complete care. Please limit your visit to this.” I spent the night in the hospital waiting room in case something happened. At dawn when I asked, “How is she?” all they would say was, “She’s stabilized for now.”

That evening [March 20] our parents, my wife and kids all came to the hospital. I didn’t know what to expect, so I had the kids come too, just to be safe. Of course they were too small to understand the situation, but seeing them eased my tension, or rather let me get some feelings out. “Something horrible’s happened to Auntie Shizuko …” I started crying. My kids were upset; they knew it was serious; they’d never seen me cry before. They tried to comfort me, “Daddy, Daddy, don’t cry!”—and then we were all crying. My parents are from an older generation: the stiff upper lip. They held back all the time they were at the hospital, but when they got home that evening they cried the whole night through.

I took a week off work. My wife did the same. Finally, on Wednesday, March 22, the doctor gave us a rundown on things. Her blood pressure and respiration had improved slightly and stabilized to some extent, but they were still testing her brain functions. She could still get worse.

There was no explanation about the effects of sarin. We were shown an X ray of her head and were told, “The brain’s swollen.” It seemed really puffed up, but whether this was due to the sarin or to prolonged oxygen starvation there was no telling as yet.

She couldn’t breathe on her own, so she was hooked up to an artificial respirator. But that couldn’t go on indefinitely, so on March 29 they opened a breathing valve in her throat. That’s how she is now.

I visited every day while Shizuko was in the hospital in Nishi-shinjuku. Every day without fail after work, for the 7:00 visiting hours, unless I was really under the weather. My boss always had someone drive me there. I lost a lot of weight, but I kept it up for five months, until August 23 when she was moved to another hospital.

In my date book, I noted that her eyes moved on March 24. They didn’t snap wide open, but rolled around slow, behind half-lifted lids. This was when I spoke to her. Again the doctor said that she wasn’t looking around recognizing things. It was just another coincidence. I was warned not to raise my expectations too high. And in fact on her. The timing was just right for her train to have hit the worst of it. I tried to stay calm; I knew it did no good to worry. I had taken the company car to see a client, when a call came in from the office. I was to contact my mother urgently. This was between 10:30 and 11:00. “We had a call from the police,” she said. “Shizuko was injured in the subway and taken to the hospital. Go quickly!”

I rushed back to the office, took the train to Shinjuku, and reached the hospital around 12:00. I’d called from the office, but couldn’t find out much about her condition over the phone: “We are not to tell members of the family anything unless they come here.”

The hospital reception was filled with victims. All of them were on drips or getting examined. That’s when I realized it was really serious, but I still didn’t know much. The television had said something about poison gas, but nothing in detail. The doctors weren’t much help either. All they told me that day was, “She inhaled a virulent chemical similar to a pesticide.”

They wouldn’t even let me see her straightaway. There I was hoping to see with my own eyes what state she was in, and they wouldn’t tell me anything or let me into the ward. The hospital was crowded and confused, and Shizuko was in Emergency Care. I could only visit her between 12:30 and 1:00 in the afternoon, and 7:00 and 8:00 at night.

I waited for two hours—two grueling hours—and then just briefly I got to see her. She was dressed in a hospital gown and lying in bed getting dialysis. Her liver was quite weak and needed help to filter out all the toxins from her blood. She was on several intravenous drips too. Her eyes were closed. According to the nurse she was in a “sleeping state.” I reached out to touch her but the doctor held me back; I wasn’t wearing gloves.

I whispered in her ear, “Shizuko, it’s your brother!” She twitched in response, or so I thought, but the doctor said her responding to my voice was practically unthinkable; she must have had a spasm in her sleep. She’d been having convulsions since they brought her in.

Her face, to be crude, looked more dead than asleep. She had an oxygen mask over her mouth, and her face had no expression whatsoever. No sign of pain or suffering or anything. The device that measured her heartbeat hardly flickered, just an occasional blip. She was that bad. I could hardly bear to look at her. April 1 they said: “Judging from the pattern of brain damage due to contusions and hemorrhages in ordinary traffic accidents, there is virtually no chance of further recovery.” In other words, while she wasn’t a “vegetable,” she would probably remain bedridden for the rest of her life. Unable to sit up, unable to speak, barely aware of anything.

It was hard to accept. My mother burst out saying, “Shizuko should have died. She’d have posed no more trouble to herself or to any of you.” Those words really cut deep; I understood my mother completely, yet how could I answer her? In the end, all I could say was, “If Shizuko was of no further use, then God would have surely let her die. But that didn’t happen. Shizuko is alive here and now. And there’s the chance she’ll get well, isn’t there? If we don’t believe that, Shizuko’s beyond hope. We have to force ourselves to believe.”

That was the hardest part for me. When my own father and mother could say such things—that Shizuko would have been better off dead—what was I supposed to say? That was about ten days after she collapsed.

Not long after that, my father had an attack. On May 6 they diagnosed cancer and he was admitted to the Kashiwa National Cancer Center for an operation. Every day I was rushing back and forth between Shizuko and my father. My mother was in no condition to move around.

In August, Shizuko was transferred to a hospital where there was a young doctor keen on therapy. And now she’s progressed to the point where she can move her right hand. Little by little, she’s able to move. Ask her, “Where’s your mouth?” and she’ll raise her right hand to her mouth.

It’s still not easy for her to speak, but she seems to understand most of what we’re saying. Only the doctor says he’s not convinced she exactly understands the relationships between the family members. I always tell her, “It’s your brother come to visit,” but whether or not she knows what a “brother” is is another matter. Most of her memory has disappeared.

If I ask her, “Where were you living before?” she can only answer, “Don’t know.” At first our parents’ names, her own age, how many brothers and sisters she had, her place of birth were all “Don’t know.” All she knew was her own name. But little by little she’s recovering her faculties. Presently she’s on two main therapy programs: physical recovery and speech recovery. She practices sitting in a wheelchair, standing on her right leg, moving her right hand, straightening her crooked leg, the vowel sounds—a, i, u, e, o.

She can still hardly move her mouth to eat, so they feed her through her nose straight to the stomach. The muscles in her throat are stiff. There’s nothing actually wrong with her vocal cords, but the muscles that control them don’t move much.

According to the doctor, the ultimate goal of therapy is for her to be able to walk out of the hospital on her own, but whether or not she’ll ever make it that far he won’t say. Still, I trust the hospital and the doctor, and I’m leaving everything in their hands.

Now I go the hospital every other day. It’s 11:00 by the time I get home, which has me shifting between two schedules. I’ve put on weight, probably because I eat and drink late at night, just before bed.

Three times a week I go alone after work. Sundays the whole family goes: my mother, too. Father’s back from the Cancer Center, but after long outings he gets a temperature, so he doesn’t come along.

It’s all on my shoulders, but it’s my family, after all. My wife’s the one I feel sorry for: if she hadn’t married me, she wouldn’t have to put up with all this. And the kids, too. If my sister was well we’d be taking vacations, going places.

But, you know, the first time Shizuko spoke, I was beside myself with joy. At first it was only a groan—uuh—but I cried when I heard it. The nurse cried too. And strangely enough, then Shizuko started crying and saying uuh aah. I have no real notion what her tears meant. According to the doctor the emotions in the brain take the unstable form of “crying out” when first expressed. So that was a first step.

On July 23 she spoke her first words in front of our parents. Shizuko cried out, “Mama.” That was the first thing they’d heard her say in four months. They both cried.

This year she’s been able to laugh. Her face can smile. She laughs at simple jokes, at me making farting noises with my mouth or anything like that. I’ll say, “Who farted?” and she’ll answer, “Brother.” She’s recovered to that extent. She still can’t speak too well; it’s difficult to tell what she’s saying, but at least she’s talking.

“What do you want to do?” I ask, and she answers “Go for walk.” She’s developed her own self-will. She can’t see much, though, only a little with her right eye.

The night before the gas attack, the family was saying over dinner, “My, how lucky we are. All together, having a good time”… a modest share of happiness. Destroyed the very next day by those idiots. Those criminals stole what little joy we had.

Right after the attack, I was insane with anger. I was pacing the hospital corridors pounding on the columns and walls. At that point I still didn’t know it was Aum, but whoever it was I was ready to beat them up. I didn’t even notice, but several days later my fist was sore. I asked my wife, “Odd, why does my hand hurt so much?” and she said, “You’ve been punching things, dear.” I was so incensed.

But now, after nearly two years, things are a lot better thanks to everyone at my sister’s company, my colleagues and my boss, the doctors and nurses. They’ve all been a great help.

“Ii-yu-nii-an [Disneyland]”

“Shizuko Akashi” (31)

I talked to Shizuko Akashi’s elder brother, Tatsuo, on December 2, 1996, and the plan was to visit her at a hospital in a Tokyo suburb the following evening.

I was uncertain whether or not Tatsuo would allow me to visit her until the very last moment. Finally he consented, though only after what must have been a considerable amount of anguished deliberation—not that he ever admitted as much. It’s not hard to imagine how indelicate it must have seemed for him to allow a total stranger to see his sister’s cruel disability. Or even if it was permissible for me as an individual to see her, the very idea of reporting her condition in a book for all the world to read would surely not go down well with the rest of the family. In this sense, I felt a great responsibility as a writer, not only toward the family but to Shizuko herself

Yet whatever the consequences, I knew I had to meet Shizuko in order to include her story. Even though I had gotten most of the details from her brother, I felt it only fair that I meet her personally. Then, even if she responded to my questions with complete silence, at least I would have tried to interview her …

In all honestly, though, I wasn’t at all certain that I would be able to write about her without hurting someone’s feelings.

Even as I write, here at my desk the afternoon after seeing her, I lack confidence. I can only write what I saw, praying that no one takes offense. If I can set it all down well enough in words, just maybe …

![]()

A wintry December. Autumn has slowly slipped past out of sight. I began preparations for this book last December, so that makes one year already. And Shizuko Akashi makes my sixtieth interviewee—though unlike all the others, she can’t speak her own mind.

By sheer coincidence, the very day I was to visit Shizuko the police arrested Yasuo Hayashi on faraway Ishigaki Island. The last of the perpetrators to be caught, Hayashi, the so-called Murder Machine, had released three packets of sarin at Akihabara Station on the Hibiya Line, claiming the lives of 8 people and injuring 250. I read the news in the early evening paper, then caught the 5:30 train for Shizuko’s hospital. A police officer had been quoted as saying: “Hayashi had tired of living on the run so long.”

Of course, Hayashi’s capture would do nothing to reverse the damage he’d already done, the lives he had so radically changed. What was lost on March 20, 1995, will never be recovered. Even so, someone had to tie up the loose ends and apprehend him.

I cannot divulge the name or location of Shizuko’s hospital. Shizuko and Tatsuo Akashi are pseudonyms, in keeping with the family’s wishes. Actually, reporters once tried to force their way into the hospital to see Shizuko. The shock would surely have set back whatever progress she’d made in her therapy program, not to mention throwing the hospital into chaos. Tatsuo was particularly concerned about that.

Shizuko was moved to the Recuperation Therapy floor of the hospital in August 1995. Until then (for the five months after the gas attack) she had been in the Emergency Care Center of another hospital, where the principal mandate was to “maintain the life of the patient”—a far cry from recuperation. The doctor there had declared it “virtually impossible for Shizuko to wheel herself to the stairs.” She’d been confined to bed, her mind in a blur. Her eyes refused to open, her muscles barely moved. Once she was removed to Recuperation, however, her progress exceeded all expectations. She now sits in a wheelchair and moves around the ward with a friendly push from the nurses; she can even manage simple conversations. “Miraculous” is the word.

Nevertheless, her memory has almost totally gone. Sadly, she remembers nothing before the attack. The doctor in charge says she’s mentally “about grade-school level,” but just what that means Tatsuo doesn’t honestly know. Nor do I. Is that the overall level of her thought processes? Is it her synapses, the actual “hardware” of her thinking circuitry? Or is it a question of “software,” the knowledge and information she has lost? At this point only a few things can be said with any certainty:

(1) Some mental faculties have been lost.

(2) It is as yet unknown whether they will ever be recovered. She remembers most of what’s happened to her since the attack, but not everything. Tatsuo can never predict what she’ll remember and what she’ll forget.

Her left arm and left leg are almost completely paralyzed, especially the leg. Having parts of the body immobilized entails various problems: last summer she had to have a painful operation to cut the tendon behind her left knee in order to straighten her crooked left leg.

She cannot eat or drink through her mouth. She cannot yet move her tongue or jaws. Ordinarily we never notice how our tongue and jaws perform complicated maneuvers whenever we eat or drink, wholly unconsciously. Only when we lose these functions do we become acutely aware of their importance. That is Shizuko’s situation right now.