The Silk Roads: A New History of the World (2016)

17

The Road of Black Gold

Few of William Knox D’Arcy’s classmates at London’s prestigious Westminster School can have thought that he would go on to have a prominent role in reshaping the world - especially when he did not arrive back for the start of term in September 1866. William’s father had been caught up in some unsavoury business in Devon that led to him being declared bankrupt and deciding to move with his family to start a new life in the quiet town of Rockhampton in Queensland, Australia.

His teenage son got on with his studies quietly and diligently enough, qualifying as a lawyer and in due course setting up his own practice. He made a comfortable living and became an upstanding member of the local community, serving on the committee of the Rockhampton Jockey Club and indulging a love for shooting whenever time permitted.

In 1882, William had a stroke of fortune. Three brothers named Morgan had been looking to exploit what they thought was a potentially large gold find at Ironside Mountain, just over twenty miles away from Rockhampton. In search of investment to help them establish a mining operation, they turned to the local bank manager, who in turn pointed them in the direction of William Knox D’Arcy. Intrigued by the possibility of a good return on his capital, Knox D’Arcy formed a syndicate with the bank manager and another mutual friend, and invested in the Morgan brothers’ scheme.

As with all mining operations at their outset, a cool head was needed as an alarming amount of cash was swallowed up in the search for a jackpot. The Morgan brothers soon lost their nerve, rattled by the rate at which their funds were being expended, and sold their interest to the three partners. They sold at just the wrong moment. The gold deposits at what had been renamed Mount Morgan turned out to be among the richest in history. Shares that had been sold in the business shot up 2,000-fold in value, while over a ten-year period the return on the investment was 200,000 per cent. Knox D’Arcy, who controlled more shares than his partners and over a third of the business, went from being a small-town lawyer in Australia to one of the richest men in the world.1

It was not long before he packed up in Australia and headed for England in triumph. He bought a magnificent town house at 42 Grosvenor Square and a suitably grand estate at Stanmore Hall, just outside London, which he had remodelled and decorated with the finest furnishings money could buy, hiring Morris & Co., the firm set up by William Morris, to take care of the interiors. He commissioned a set of tapestries from Edward Burne-Jones that took four years to weave, such was their quality. Entirely appropriately, they celebrated the quest for the Holy Grail - a suitable cipher for the discovery of incalculable treasure.2

Knox D’Arcy knew how to live the good life, renting a fine shooting estate in Norfolk and taking a box by the finishing post at the Epsom races. Two drawings in the National Portrait Gallery capture his character perfectly. One has him sitting back contentedly, with a jovial smile on his face, his generous girth testimony to his enjoyment of fine food and excellent wines; the other has him leaning forward as if to share stories of his business adventures with a friend, champagne glass in front of him, cigarette in hand.3

His success and extraordinary wealth made him an obvious man to seek out for those who, like the Morgan brothers, needed investors. One such was Antoine Kitabgi, a well-connected official in the Persian administration who was put in touch with Knox D’Arcy towards the end of 1900 by Sir Henry Drummond-Wolff, former British envoy in Teheran. Despite being a Catholic from a Georgian background, Kitabgi had done well for himself in Persia, rising to become director-general of Persian Customs and a man with fingers in many pies. He had been involved in several attempts to draw in investment from abroad to stimulate the economy, negotiating or attempting to negotiate concessions for outsiders to take positions in the banking sector and in the production and distribution of tobacco.4

These efforts were not entirely motivated by altruism or patriotism, for men like Kitabgi realised that they could parlay their connections into lucrative rewards if and when deals were agreed. Their line of business was opening doors in return for money. This was a source of deep irritation in London, Paris, St Petersburg and Berlin, where diplomats, politicians and businessmen found the Persian way of operating opaque, if not downright corrupt. Efforts to modernise the country had made little progress, while the old tradition of relying on foreigners to run the armed forces or take key administrative roles resulted in frustration all round.5 Every time Persia took one step forward, it seemed to take another back.

It was all very well criticising the ruling elite, but they had long been trained to behave in this way. The Shah and those around him were like over-indulged children who had been taught that if they held out long enough, they would be rewarded by the great powers, who were terrified that they would lose position in this strategically crucial region if they did not cough up. When Shah Moẓaffar od-Dīn was not invested with the Order of the Garter during his visit to England in 1902 and refused to accept any lesser honour, he left the country making it clear he was ‘very unhappy’; this prompted senior diplomats to set about convincing the reluctant King Edward VII, in whose gift membership of the order lay, to invest the Shah after his return home. Even then there were mishaps with this ‘terrible subject’ when it was discovered that the Shah did not possess knee-breeches, which were deemed essential to the investiture - until one resourceful diplomat discovered a precedent where a previous recipient had received the honour wearing trousers. ‘What a nightmare that Garter episode was,’ grumbled the Foreign Secretary Lord Lansdowne afterwards.6

And in fact, while the bribery that went hand in hand with getting anything done in Persia seemed vulgar, in many ways the Persians who scuttled back and forth through the corridors of power and the great financial centres of Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were not dissimilar to the Sogdian traders of antiquity who travelled over long distances to do business, or the Armenians and Jews who played the same role in the early modern period. The difference was that where the Sogdians had to take goods with them to sell, their later peers were selling their services and their contacts. These had been commoditised precisely because there were handsome rewards to be made. Had there been no takers, doubtless things would have been rather different. As it was, Persia’s location between east and west, linking the Gulf and India with the tip of Arabia, the Horn of Africa and access to the Suez Canal, meant that it was courted at no matter what cost - albeit through gritted teeth.

When Kitabgi approached Drummond-Wolff and was put in touch with Knox D’Arcy, who was described as ‘a capitalist of the highest order’, he had his eye not on Persia’s tobacco or banking sector but on its mineral wealth. And Knox D’Arcy was the perfect person to talk to. He had struck gold once before in Australia; Kitabgi offered him the chance to do so again; this time it was black gold that was at stake.7

The existence of substantial oil deposits in Persia was hardly a secret. Byzantine authors in late antiquity wrote regularly of the destructive power of ‘Median fire’, a substance made from petroleum most likely taken from surface seepages in northern Persia comparable to the inflammable ‘Greek fire’ that the Byzantines made from outflows in the Black Sea region.8

The first systematic geological surveys in the 1850s had pointed to the likelihood of substantial resources below the surface and led to a series of concessions being given to investors, lured by the prospect of making their fortunes at a time when the world seemed to be disgorging its treasures to lucky prospectors, from California Gold Country to the Witwatersrand basin in southern Africa.9 Baron George de Reuter, founder of the eponymous news agency, was one who moved in on Persia. In 1872, de Reuter gained ‘the exclusive and definite privilege’ to extract whatever he could from ‘the mines of coal, iron, copper, lead and petroleum’ across the whole of the country, as well as options on the construction of roads, public works and other infrastructure projects.10

For one reason or another, these came to nothing. There was fierce local opposition to the grant of licences, with populist figures like Sayyid Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī deploring the fact that ‘the reins of the government [were being] handed to the enemy of Islam’. As one of the most vocal critics wrote, ‘the realms of Islam will be soon under the control of foreigners, who will rule therein as they please and do as they will’.11 There was also international pressure to contend with, which led to the original de Reuter concession being declared null and void barely a year after it had been agreed.12

Although de Reuter agreed a second concession in 1889 that gave him the rights to all Persia’s mineral resources other than precious metal - in return for substantial ‘gifts’ of money to the Shah and his key officials as well as an agreed royalty payment on future profits - this lapsed when efforts to find oil that could be exploited in commercially viable quantities failed within the designated ten-year time frame. Life had not been made any easier by what one leading British businessman described as ‘the backward state of the country, and the absence of communication and transport’, made worse by the ‘direct hostility, opposition and outrage from high officials of the Persian Government’.13 Nor was there any sympathy in London. There were risks to doing business in this part of the world, one internal minute noted; anyone who expected things to work as they did in Europe was extremely foolish. ‘It is their own fault’ if expectations were left disappointed, it stated coldly.14

Knox D’Arcy was, nevertheless, intrigued by the proposition put to him by Kitabgi. He studied the findings of the French geologists who had been surveying the country for the best part of a decade and took soundings from Dr Boverton Redwood, one of Britain’s leading experts on petroleum and author of handbooks on oil production and on the safe storage, transportation, distribution and use of petroleum and its products.15 There was no need to do all this research, Kitagbi meanwhile assured Drummond-Wolff, asserting that ‘we are in the presence of a source of riches [that are] incalculable’.16

Knox D’Arcy was interested enough by what he read and heard to strike a deal with those whose help would be needed to win a concession from the Shah, namely Edouard Cotte, who had served as de Reuter’s agent and was therefore a familiar face in Persian circles, and Kitabgi himself - while Drummond-Wolff was also promised a reward further down the line should the project be successful. Knox D’Arcy then approached the Foreign Office to get its blessing for the project, and duly sent his representative Alfred Marriott to Teheran to commence negotiations with a formal letter of introduction.

While the letter itself had little intrinsic value, requesting simply that the bearer be offered whatever assistance he may require, in a world where signals could easily be misread the signature of the Foreign Secretary was a powerful tool, suggesting that the British government stood behind Knox D’Arcy’s initiative.17 Marriott looked at the Persian court with wonder. The throne, he wrote in his journal, was ‘entirely encrusted with diamonds, sapphires and emeralds, and there are jewelled birds (not peacocks) standing on the sides’; at least, he was able to report, the Shah was an ‘exceedingly good shot’.18

In fact, the real work was done by Kitabgi, who according to one report managed to secure ‘in a very thorough manner the support of all the Shah’s principal Ministers and courtiers, not even forgetting the personal servant who brings His Majesty his pipe and morning coffee’ - a euphemism for greasing their palms. Things were going well, Knox D’Arcy was told; it seemed likely that a petroleum concession would ‘be granted by the Persian government’.19

The process of getting an agreement in writing was tortuous. Unseen obstacles appeared from nowhere, prompting cables back to London to ask for advice from Knox D’Arcy - and for authorisation to fork out still more. ‘I hope you will approve this as to refuse would be to lose the affair,’ Marriott urged. ‘Don’t scruple if you can propose anything for facilitating affairs on my part,’ came the reply.20 Knox D’Arcy meant that he was happy to be liberal with his money, and was willing to do whatever it took to get what he wanted. It was impossible to tell when new demands were made or promises given as to who the real beneficiaries were; there were rumours that the Russians had got wind of the negotiations, which were supposedly being conducted in secret, and false trails were laid to put them off the scent.21

And then, almost without warning, word came through (while Marriott was at a dinner party in Teheran) that the Shah had signed the agreement. In return for £20,000, with the same amount in shares to be paid on the formation of the company, plus an annual royalty of 16 per cent on net profits, Knox D’Arcy, described in the formalities as a man ‘of independent means residing in London at No. 42 Grosvenor Square’, was granted sweeping rights. He was awarded ‘a special and exclusive privilege to search for, obtain, exploit, develop, render suitable for trade, carry away and sell natural gas, petroleum, asphalt and ozokerite throughout the whole extent of the Persian Empire for a term of 60 years’. In addition, he received the exclusive right of laying pipelines, establishing storage facilities, refineries, stations and pump services.22

A royal proclamation that followed announced that Knox D’Arcy and ‘all his heirs and assigns and friends’ had been granted ‘full powers and unlimited liberty for a period of sixty years to probe, pierce and drill at their will the depths of Persian Soil’, and entreated ‘all officials of this blessed kingdom’ to help a man who enjoyed ‘the favour of our splendid court’.23 He had been handed the keys to the kingdom; the question was whether he could now find the lock.

Experienced observers in Teheran were not convinced. Even if ‘petroleum is discovered, as their agents believe will be the case’, noted Sir Arthur Hardinge, Britain’s representative to Persia, major challenges lay ahead. It was worth remembering, he went on, that ‘the soil of Persia, whether it contains oil or not, has been strewn of late years with wrecks of so many hopeful schemes of commercial and political regeneration that it would be rash to predict the future of this latest venture’.24

Perhaps the Shah too was gambling that little would come of the affair and that he could simply help himself to upfront payments as he had done in the past. It was certainly true that the economic situation in Persia at this time was dire: the government was facing a major budgetary shortfall, producing a precarious and worrying deficit, with the result that it was worth cutting corners to get money from Knox D’Arcy’s deep pockets. This was also a time of intense anxiety within the British Foreign Office, which paid much less attention to the newly awarded concession than it did to the overtures Teheran was making both to London and, worryingly, to St Petersburg in the years before the First World War.

The Russians reacted badly to news of the Knox concession. As it was, they had almost managed to derail the award when the Shah received a personal telegram from the Tsar urging him not to proceed.25 Knox D’Arcy had been sufficiently worried that Russian noses would be put out of joint by the agreement that he had directed that rights in the northern provinces be specifically excluded so as ‘to give no umbrage’ to Persia’s powerful northern neighbour. From London’s point of view, the worry was that Russia would over-compensate for losing out by being more accommodating to the Shah and his officials than ever.26 As Britain’s representative in Teheran warned Lord Lansdowne, the award of a concession might be ‘fraught with political and economic results’ if oil was found in any meaningful quantity.27 There was no disguising the truth that pressure was ratcheting up in the rivalry for influence and resources in the Gulf region.

In the short term things blew over, largely because Knox D’Arcy’s project seemed doomed to failure. Work was slow thanks to the difficult climate, the large number of religious festivals and the regular and dispiriting mechanical failure of the rigs and drills. There was open hostility too in the form of complaints about pay, about working practices and about the small number of locals who were employed, while there was also no end of trouble with local tribes wanting to be bought off.28 Knox D’Arcy grew nervous about the lack of progress and how much of his money was being spent. ‘Delay serious’, he cabled his drilling team less than a year after the concession was agreed; ‘pray expedite’.29 A week later, he sent another dispatch: ‘have you free access to wells?’ he asked his chief engineer in despair. Logbooks reveal large quantities of pipes, tubes, shovels, steel and anvils being shipped from Britain, alongside rifles, pistols and ammunition. Wage slips from 1901-2 also show funds being spent in ever increasing quantities. It must have felt to Knox D’Arcy that he was burying his money in the sand.30

If he was anxious, then so too were his bankers at Lloyds, who became increasingly perturbed about the size of the overdraft of a man they had assumed had limitless funds at his disposal.31 What made it worse was that there was little to show for the hard work and high costs: Knox D’Arcy needed to convince other investors to buy shares in the business and thereby take pressure off his personal cash flows and provide the capital to take things forward. His teams were producing promising signs of oil; what he needed was a major strike.

As he grew increasingly desperate, Knox D’Arcy sounded out potential investors or even buyers for his concession, travelling to Cannes to meet with Baron Alphonse de Rothschild, whose family already had extensive interests in the oil business in Baku. This set off alarm bells in London. In particular, it caught the attention of the British navy: Sir John Fisher, First Lord of the Admiralty, had become evangelical in his belief that the future of naval warfare and of mastery of the seas lay in switching from coal to oil. ‘Oil fuel’, he wrote to a friend in 1901, ‘will absolutely revolutionise naval strategy. It’s a case of “Wake up England!”’32 Despite the failure to deliver a knock-out discovery, all the evidence suggested that Persia had the potential to be a major source of oil. If this could be secured for the exclusive use of the Royal Navy, then so much the better. But it was essential that control of such resources should not be surrendered into foreign hands.

The Admiralty stepped in to broker an agreement between Knox D’Arcy and a Scottish oil company that had met with considerable success in Burma. After offering a contract to the latter in 1905 to supply the navy with 50,000 tons of oil per annum, the directors of the Burmah Oil Company were persuaded to take a major stake in what was renamed the Concessions Syndicate. They did so not out of patriotic duty but because it was a sensible diversification strategy, and because their track record also enabled them to raise more capital. Although this allowed Knox D’Arcy to breathe a sigh of relief, writing that the terms he had achieved ‘were better than I could have obtained from any other company’, there was still no guarantee of success - as the ever sceptical British diplomatic representative in Teheran noted drily in his reports home. Finding oil was one problem; handling persistent attempts at blackmail was another.33

True enough, the new partnership had little to show for its efforts over the next three years. Wells that were drilled failed to bear fruit, while expenditure ate away at the finances of shareholders. By the spring of 1908, the directors of the Burmah Oil Company were openly talking about pulling out of Persia altogether. On 14 May 1908, they sent word to George Reynolds, leader of operations in the field and a man described by one of those who worked with him as single-minded, determined and made of ‘solid British oak’, to prepare to abandon operations. He was instructed to drill two wells that had been established at Masjed Soleymān to a depth of 1,600 feet. If no oil were found, he should ‘abandon operations, close down and bring back as much of the plant as is possible’, and ship it to Burma where it would prove more useful.34

As the letter made its way through the post houses of Europe and the Levant and on to Persia, Reynolds carried on with his job, unaware of how close he was to being shut down. His team kept drilling, forcing a way through rock so hard that it forced the drill bit loose. The bit was lost in the hole for several days; as the clock was ticking down, it was finally recovered and reattached. On 28 May, at four in the morning, they hit the motherlode, striking oil and sending black gold shooting high into the air. It was a huge find.35

Arnold Wilson, a British army lieutenant who was in charge of the security of the site, sent a coded cable back home with the news. It simply said: ‘See Psalm 104, verse 15 second sentence.’36 The verse entreated the good Lord to bring forth from the earth oil to make faces shine with happiness. The discovery, he told his father, promised fabulous rewards for Britain - and hopefully, he added, for the engineers ‘who have persevered so long, in spite of their top-hatted directors … in this inhospitable climate’.37

Investors who piled into the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, the vehicle that controlled the rights to the concession, after shares were offered in 1909 reckoned that the first well at Masjed Soleymān was just the tip of the iceberg and there would be high rewards in the future. Naturally, it would take time and money to build up the infrastructure necessary to allow oil to be exported, as well as to drill new wells and find new fields. Nor was it easy running things smoothly on the ground, where Arnold Wilson complained he had to spend time bridging the cultural gap between the British ‘who cannot say what they mean and Persians who do not always mean what they say’. The British, he declared, saw a contract as an agreement that would stand up in court; the Persians simply saw it as an expression of intentions.38

Nevertheless, a pipeline was soon built to connect the first field to the island of Ābādān in the Sha![]()

![]() al-

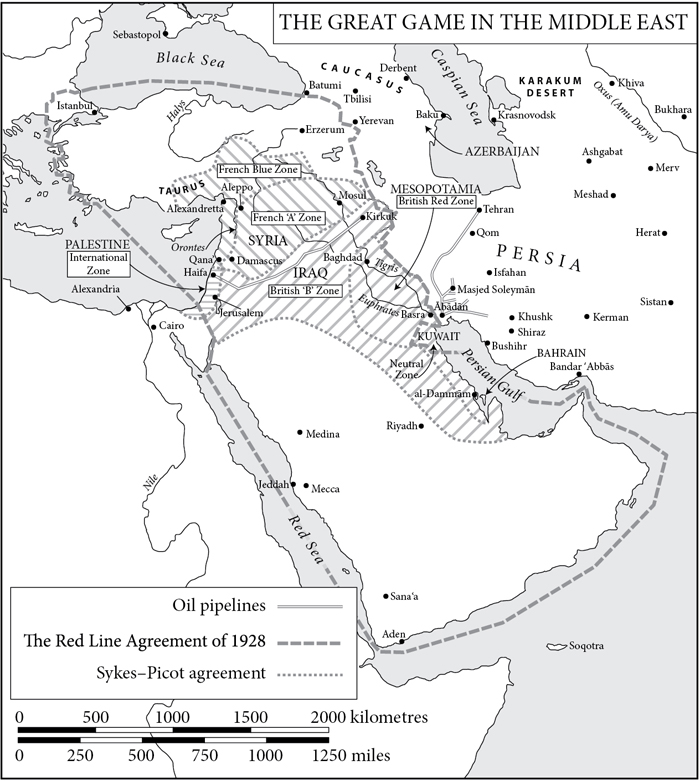

al-![]() Arab, which had been chosen as the location for a refinery and export centre. It took Persia’s oil to the Gulf, where it could then be loaded on to ships and brought back to Europe to be sold at a time when the continent’s energy needs were rising sharply. The pipeline itself was highly symbolic, for it marked the first strand in what was to become a web of pipelines criss-crossing Asia that gave new form and life to the old Silk Roads.

Arab, which had been chosen as the location for a refinery and export centre. It took Persia’s oil to the Gulf, where it could then be loaded on to ships and brought back to Europe to be sold at a time when the continent’s energy needs were rising sharply. The pipeline itself was highly symbolic, for it marked the first strand in what was to become a web of pipelines criss-crossing Asia that gave new form and life to the old Silk Roads.

Problems were brewing. The discovery of oil made the piece of paper signed by the Shah in 1901 one of the most important documents of the twentieth century. For while it laid the basis for a multi-billion-dollar business to grow - the Anglo-Persian Oil Company eventually became British Petroleum - it also paved the way for political turmoil. That the terms of the agreement handed control of Persia’s crown jewels to foreign investors led to a deep and festering hatred of the outside world, which in turn led to nationalism and, ultimately, to a more profound suspicion and rejection of the west best epitomised in modern Islamic fundamentalism. The desire to win control of oil would be the cause of many problems in the future.

On a human level, Knox D’Arcy’s concession is an amazing tale of business acumen and triumph against the odds; but its global significance is on a par with Columbus’ trans-Atlantic discovery of 1492. Then too, immense treasures and riches had been expropriated by the conquistadors and shipped back to Europe. The same thing happened again. One reason for this was the close interest paid by Admiral Fisher and the Royal Navy, who monitored the situation in Persia closely. When Anglo-Persian experienced cash-flow problems in 1912, Fisher was quick to step in, concerned that the business might be acquired by producers like Royal Dutch/Shell, which had built up a substantial production and distribution network from an initial base in the Dutch East Indies. Fisher went to see the First Lord of the Admiralty, a rising political star, to impress on him the importance of converting the engines of naval battleships from coal-burning to oil. Oil is the future, he declared; it could be stored in large quantities and was cheap. Most important, however, was that it enabled ships to move faster. Naval warfare ‘is pure common sense’, he said. ‘The first of all necessities is SPEED, so as to be able to fight - When you like, Where you like and How you like.’ It would allow British ships to outmanoeuvre enemy ships and give them a decisive edge in battle.39Listening to Fisher, Winston Churchill understood what this meant.

Switching to oil would mean that the power and efficiency of the Royal Navy would be raised to ‘a definitely higher level; better ships, better crews, higher economies, more intense forms of war power’. It meant, as Churchill noted, nothing less than that the mastery of the seas was at stake.40 At a time when pressure was rising in international affairs and confrontation looked increasingly likely in some form or other, whether in Europe or elsewhere, considerable thought went into how this advantage could be established and pressed home. In the summer of 1913, Churchill presented a paper to the Cabinet entitled ‘Oil Fuel Supply for His Majesty’s Navy’. The solution, he argued, was to buy fuel forward from a range of producers, and even to consider taking ‘a controlling interest in trustworthy sources of supply’. The discussion that followed did not lead to a definite conclusion, other than an agreement that the ‘Admiralty ought to secure its oil supplies … from the widest possible area and the most numerous sources of supply’.41

Less than a month later, things had changed. The Prime Minister now believed, along with his ministers, in the ‘vital necessity’ of oil in the future. He therefore told King George V in his regular round-up of noteworthy developments that the government was going to take a controlling state in Anglo-Persian, in order to secure ‘trustworthy sources of supply’.42

Churchill was vocal in championing his cause. Securing oil supplies was not just about the navy; it was about safeguarding Britain’s future. Although he saw that coal underpinned the empire’s success, it was oil on which much depended. ‘If we cannot get oil,’ he told Parliament in July 1913, ‘we cannot get corn, we cannot get cotton and we cannot get a thousand and one commodities necessary for the preservation of the economic energies of Great Britain.’ Reserves should be built up in case of war; but the open market could also not be trusted - because it was becoming ‘an open mockery’ thanks to the efforts of speculators.43

Anglo-Persian therefore seemed to offer the solution to many problems. Its concession was ‘thoroughly sound’ and, with sufficient funds behind it, could probably be ‘developed to a gigantic extent’, according to Admiral Sir Edmond Slade, formerly director of naval intelligence and head of the task force in charge of running the rule over the company. Control of the company, with the guaranteed oil supply this would entail, would be a godsend for the navy. The key, concluded Slade, was taking a majority stake ‘at a very reasonable cost’.44

Negotiations with Anglo-Persian moved quickly enough that by the summer of 1914 the British government was in a position to buy a 51 per cent stake - and, with it, operational control of the business. Churchill’s eloquence in the House of Commons saw a large majority vote in favour. And so it was that British policymakers, planners and military could take comfort in the knowledge that they had access to oil resources that could prove vital in any military conflict in the future. Eleven days later, Franz Ferdinand was shot dead in Sarajevo.

In the flurry of activity that surrounded the build-up to war, it was easy to overlook the importance of the steps Britain had taken to safeguard its energy needs. This was partly because few realised just what deals had been done behind the scenes. For in addition to buying a majority stake in Anglo-Persian, the British government had also agreed terms in secret for a twenty-year supply of oil for the Admiralty. This meant that Royal Navy ships that put to sea in the summer of 1914 did so with the benefit that they could bank on being refuelled should confrontation with Germany drag on. Conversion to oil made British vessels faster and better than their rivals; but the most important advantage was that they could stay out at sea. Not for nothing did Lord Curzon give a speech in London in November 1918, less than two weeks after the armistice had been agreed, in which he told fellow dinners that ‘the Allied cause had floated to victory upon a wave of oil’. A leading French senator agreed jubilantly. Germany had paid too much attention to iron and coal, he said, and not enough to oil. Oil was the blood of the earth, he said, and it was the blood of victory.45

There was some truth in this. For while the attention of military historians focuses on the killing fields of Flanders, what happened in the centre of Asia was of major significance to the outcome of the Great War - and even more important to the period that followed. As the first shots were being fired in Belgium and northern France, the Ottomans were pondering what role they should play in the escalating confrontation in Europe. While the Sultan was adamant that the empire should stay out of the war, other loud voices argued that cementing traditionally close links with Germany into an alliance was the best course of action. As the great powers of Europe were busy issuing ultimata and declaring war on each other, Enver Pasha, the mercurial Ottoman Minister of War, contacted the commander of the army headquarters in Baghdad to warn him of what might lie ahead. ‘War with England is now within the realm of possibilities,’ he wrote. If hostilities broke out, he went on, Arab leaders should be roused to support the Ottoman military effort in a holy war. The Muslim population of Persia should be roused to revolution against ‘Russian and English rule’.46

In this context, it was not surprising that within weeks of the start of the war, a British division was dispatched from Bombay to secure Ābādān, the pipelines and the oilfields. When this had been done, the strategically sensitive town of Basra was occupied in November 1914, whereupon the town’s inhabitants were told by Sir Percy Cox during a flag-raising ceremony that ‘no remnant of the Turkish administration remains in this place. In place thereof, the British flag has been established, under which you will enjoy the benefits of liberty and justice, both in regard to your religious and secular affairs.’47 The customs and beliefs of the locals mattered little; what was important was protecting access to the natural resources of the region.

Aware that their hold over the Gulf region was tenuous, the British made overtures to leading figures in the Arab world, including ![]() usayn, Sharīf of Mecca, who was offered a tempting deal: if

usayn, Sharīf of Mecca, who was offered a tempting deal: if ![]() usayn ‘and the Arabs in general’ were to provide support against the Turks, then Britain ‘will guarantee the independence, rights and privileges of the Sharifate against all external foreign aggression, in particular that of the Ottomans’. That was not all, for another, even juicier incentive was offered up too. Perhaps the time had come when ‘an Arab of true race will assume the Caliphate at Mecca or Medina’.

usayn ‘and the Arabs in general’ were to provide support against the Turks, then Britain ‘will guarantee the independence, rights and privileges of the Sharifate against all external foreign aggression, in particular that of the Ottomans’. That was not all, for another, even juicier incentive was offered up too. Perhaps the time had come when ‘an Arab of true race will assume the Caliphate at Mecca or Medina’. ![]() usayn, guardian of the holy city of Mecca and a member of the Quraysh, and descendant of Hāshim, the great-grandfather of the Prophet Mu

usayn, guardian of the holy city of Mecca and a member of the Quraysh, and descendant of Hāshim, the great-grandfather of the Prophet Mu![]() ammad himself, was being offered an empire in return for his support.48

ammad himself, was being offered an empire in return for his support.48

The British did not really mean this, and nor could they really deliver it. However, from the start of 1915, as things took a turn for the worse, they were prepared to string ![]() usayn along. This was partly because a swift triumph in Europe had not materialised. But it also stemmed from the fact that the Ottomans were finally beginning to counter-attack against the British position in the Persian Gulf - and also, worryingly, in Egypt too, threatening the Suez canal, the artery that enabled ships from the east to reach Europe weeks faster than if they had to circumnavigate Africa. To divert Ottoman resources and attention, the British decided to land troops in the eastern Mediterranean and open a new front. In the circumstances, cutting deals with anyone who might take the pressure off the Allied forces seemed an obvious thing to do; and it was easy to over-promise rewards that might only be paid far in the future.

usayn along. This was partly because a swift triumph in Europe had not materialised. But it also stemmed from the fact that the Ottomans were finally beginning to counter-attack against the British position in the Persian Gulf - and also, worryingly, in Egypt too, threatening the Suez canal, the artery that enabled ships from the east to reach Europe weeks faster than if they had to circumnavigate Africa. To divert Ottoman resources and attention, the British decided to land troops in the eastern Mediterranean and open a new front. In the circumstances, cutting deals with anyone who might take the pressure off the Allied forces seemed an obvious thing to do; and it was easy to over-promise rewards that might only be paid far in the future.

Similar calculations were being made in London about the rise of Russian power. Although the horrors of war quickly became apparent, there were some influential figures in Britain who were concerned that the war would end too soon. The former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour was anxious that a rapid defeat of Germany would make Russia more dangerous still by fuelling the ambitions of the latter to the extent that India might be at risk. There was another worry: Balfour had also heard rumours that a well-connected lobby in St Petersburg was trying to come to terms with Germany; this, he reckoned, would be as disastrous for Britain as losing the war.49

Concerns about Russia meant that ensuring its loyalty was of paramount importance. The prospect of control of Constantinople and the Dardanelles was the perfect bait to retain the bonds that united the Allies and to draw the tsarist government’s attention towards an acutely sensitive topic. Mighty though Russia was, its Achilles heel was its lack of warm-water ports other than in the Black Sea, which was connected to the Mediterranean first by the Bosporus and second by the Dardanelles, the narrow stretches of water separating Europe from Asia at either end of the Sea of Marmara. These channels served as a lifeline, connecting the grainfields of southern Russia with export markets abroad. Closure of the Dardanelles, leaving wheat to rot in the storehouses, had inflicted devastating damage on the economy during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and had led to talk of war being declared on the Ottomans who controlled them.50

The Russians were delighted, therefore, when the British raised the question of the future of Constantinople and the Dardanelles at the end of 1914. This was ‘the richest prize of the entire war’, Britain’s ambassador announced to the Tsar’s officials. Control was to be handed to Russia once the war was over, though Constantinople ought to remain a free port ‘for goods in transit to and from non-Russian territory’, alongside the concession that ‘there shall be commercial freedom for merchants ships passing through the Straits’.51

Although there was little sign of a breakthrough on the western front, with both sides suffering extraordinarily heavy losses and with years of bloodshed still in prospect, the Allies were already sitting down to carve up the lands and interests of their rivals. There is no little irony in this considering the charges of imperialism that were laid against Germany and its partners after the armistice. Just months after the war had started, the Allies were already thinking of feasting on the carcasses of their defeated enemies.

In this sense, there was more at stake than dangling the carrots of Constantinople and the Dardanelles before the Russians, for at the start of 1915 a commission under the chairmanship of Sir Maurice de Bunsen was set up to report on proposals for the future of the Ottoman Empire after victory had been assured. Part of the trick was dividing things up in a way that suited those who were allies at present but rivals in the past, and potentially in the future too. Nothing should be done, wrote Sir Edward Grey, to arouse suspicions that Britain had designs on Syria. ‘It would mean a break with France’, he wrote, ‘if we put forward any claims in Syria and Lebanon’ - a region that had seen substantial investment by French businesses in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.52

In order, therefore, to show solidarity with Russia and to avoid confrontation with France over its sphere of influence in Syria, it was decided to land a large force made up of troops from Britain, Australia and New Zealand not, as had originally been planned, at Alexandretta (now in south-eastern Turkey) but on the Gallipoli peninsula at the mouth of the Dardanelles Straits that guarded access to Constantinople.53 It was a landing site that proved to be singularly ill suited to hosting a major offensive, and a death trap for many of those who tried to fight their way on to land, uphill against well-fortified Turkish positions. The disastrous campaign that followed had at its origins the struggle to establish control over the communication and trade networks linking Europe with the Near East and Asia.54

The future of Constantinople and the Dardanelles had been set out; now that of the Middle East needed to be resolved. In a series of meetings in the second half of 1915 and at the start of 1916, Sir Mark Sykes, an over-confident MP who had the ear of Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, and François Georges-Picot, an uppity French diplomat, divvied up the region. A line was agreed by the two men, which stretched from Acre (in the far north of what is now Israel) north-eastwards as far as the frontier with Persia. The French would be left to their own devices in Syria and Lebanon, the British to theirs - in Mesopotamia, Palestine and Suez.

Dividing up the spoils in this way was dangerous, not least since conflicting messages about the future of the region were being transmitted elsewhere. There was ![]() usayn, who was still being offered independence for the Arabs and the restitution of a caliphate, with him at the head; there were the peoples of ‘Arabia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine’, who the British Prime Minister was busy stating publicly should be ‘entitled to a recognition of their separate national conditions’, seemingly a promise of sovereignty and independence.55 Then there was the United States, which had received repeated assurances from the British and French that they were fighting ‘not for selfish interests but, above all, to safeguard the independence of peoples, right and humanity’. Both Britain and France passionately claimed to have noble aims at heart and were striving to set free ‘the populations subject to the bloody tyranny of the Turks’, according to The Times of London.56 ‘It was all bad,’ wrote Edward House, President Wilson’s foreign policy adviser, when he found out about the secret agreement from the British Foreign Secretary. The French and the British ‘are making [the Middle East] a breeding place for future war’.57 He was not wrong about that.

usayn, who was still being offered independence for the Arabs and the restitution of a caliphate, with him at the head; there were the peoples of ‘Arabia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine’, who the British Prime Minister was busy stating publicly should be ‘entitled to a recognition of their separate national conditions’, seemingly a promise of sovereignty and independence.55 Then there was the United States, which had received repeated assurances from the British and French that they were fighting ‘not for selfish interests but, above all, to safeguard the independence of peoples, right and humanity’. Both Britain and France passionately claimed to have noble aims at heart and were striving to set free ‘the populations subject to the bloody tyranny of the Turks’, according to The Times of London.56 ‘It was all bad,’ wrote Edward House, President Wilson’s foreign policy adviser, when he found out about the secret agreement from the British Foreign Secretary. The French and the British ‘are making [the Middle East] a breeding place for future war’.57 He was not wrong about that.

At the root of the problem was that Britain knew what was at stake thanks to the natural resources that had been found in Persia, and which Mesopotamia also seemed likely to possess. Indeed, a concession for the oil of the latter was approved (though not formally ratified) on the day of Franz Ferdinand’s assassination in 1914. It was given to a consortium led by the Turkish Petroleum Company, in which Anglo-Persian was the majority shareholder, with minority stakes given to Royal Dutch/Shell and Deutsche Bank and a sliver to Calouste Gulbenkian, the deal-maker extraordinaire who had put the agreement together.58 Whatever was being promised or committed to the peoples and nations of the Middle East, the truth was that behind the scenes the shape and the future of the region was being dreamed up by officials, politicians and businessmen who had one thing in mind: securing control over oil and the pipelines that would pump it to ports to be loaded on to tankers.

The Germans realised what was going on. In a briefing paper that found its way into British hands, it was contended that Britain had two overriding strategic goals. First was to retain control of the Suez canal, because of its unique strategic and commercial value; second was to hold on to the oilfields in Persia and the Middle East.59 This was a shrewd assessment. Britain’s sprawling trans-continental empire covered nearly a quarter of the globe. Despite the many different climates, ecosystems and resources it encompassed, there was one obvious lack: oil.

With no meaningful deposits to speak of in any of its territories, the war offered Britain the chance to put that right. ‘The only big potential supply’, wrote Sir Maurice Hankey, bookish Secretary to the War Cabinet, ‘is the Persian and Mesopotamian supply.’ As a result, establishing ‘control of these oil supplies becomes a first-class war aim’.60 There was nothing to be gained in this region from a military perspective, Hankey stressed when he wrote to the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, the same day; but Britain should act decisively if it was ‘to secure the valuable oil wells’ in Mesopotamia.61

Few needed convincing. Before the war ended, the British Foreign Secretary was talking in uncompromising terms about how the future looked to him. There were doubtless questions ahead concerning the dismemberment of their rivals’ empires. ‘I do not care’, he told senior figures, ‘under what system we keep the oil, whether it is by perpetual lease or whatever it may be, but I am quite clear it is all-important for us that this oil should be available.’62

There were good reasons for such determination - and for the anxieties that underpinned it. At the start of 1915, the Admiralty had been consuming 80,000 tons of oil per month. Two years later, as a result of the larger number of ships in service and the proliferation of oil-burning engines, the amount had more than doubled to 190,000 tons. The needs of the army had spiralled up even more dramatically, as the fleet of 100 vehicles in use in 1914 swelled to tens of thousands. By 1916, the strain had all but exhausted Britain’s oil reserves: stocks of petrol that stood at 36 million gallons on 1 January plummeted to 19 million gallons six months later, falling to 12.5 million just four weeks after that.63 When a government committee looked into likely requirements for the coming twelve months, it found that estimates indicated that there would be barely half the amount available to satisfy likely demand.64

Although the introduction of petrol rationing with immediate effect did something to stabilise stock levels, continued concerns about problems of supply led to the First Sea Lord ordering Royal Navy vessels to spend as much time in harbour as possible in the spring of 1917, while cruising speed was limited to twenty knots when out at sea. The precariousness of the situation was underlined by projections prepared in June 1917 that by the end of the year the Admiralty would have no more than six weeks’ supplies in reserve.65

This was all made worse by Germany’s development of effective submarine warfare. Britain had been importing oil in large quantities from the United States (and at increasingly high prices), but many of the tankers did not make it through. The Germans had managed to sink ‘so many fuel oil ships’, wrote Walter Page, the US ambassador to London, in 1917, that ‘this country may very soon be in a perilous condition’.66 A revolution in technology that enabled engines to run more quickly and more effectively had accompanied the rapid mechanisation of warfare after 1914. Both were driven by the ferocious land-war in Europe. But in turn the rise in consumption meant that the question of access to oil, which had already been a serious concern before the outbreak of hostilities, became a major - if not the decisive - factor in British international policy.

Some British policymakers had high hopes of what lay ahead. One experienced administrator, Percy Cox, who had served in eastern Persia and knew the country well, suggested in 1917 that Britain had the chance to gain such a tight grip on the Persian Gulf that the Russians, the French, the Japanese, the Germans and the Turks could be excluded permanently.67 As a result, although the collapse of Russia into revolution in 1917 and the peace settlement with Germany soon after the Bolshevik seizure of power was worrying as far as the war in Europe was concerned, it brought a silver lining elsewhere. Under autocratic rule, Lord Balfour told the Prime Minister in the summer of 1918, Russia had been ‘a danger to her neighbours; and to none of her neighbours so much as ourselves’.68 Its implosion was good news for Britain’s position in the east. There arose a real opportunity to cement control over the whole region that stretched between Suez and India, thereby securing both.