A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Corn (Zea mays)

Family: Gramineae: sweet grass family

Other Names: baby corn, Indian corn, sweet corn, corn on the cob, maize, popcorn

Healing Properties: pure corn oil lowers cholesterol; corn silk aids urinary ailments and promotes urination (diuretic)

Symbolic Meaning: mother goddess (Native American), life energy, wholeness, material wealth, Americanism

Planetary Affiliation: Saturn, Sun

Cereal grains are the pillars of the great civilizations. The cultures of East Asia are hardly imaginable without the delicate, semi-aquatic grass: the rice plant. The rice farmers of Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia see rice as an emanation of the benevolent Buddha. In western Europe and western Asia wheat is the “staff of life,” the “body of the Lord,” which constitutes, thus, the “communion with God.” In America, corn plays a similar role as the divine creator of civilization. “Our life,” “life giver,” and “sustainer of life” are some of the typical names various Native Americans have given to corn. The Aztecs called it “tonácatl,” (our flesh). For the Mayans corn is the “first father.” The Ojibwa called it “mondamin,” (miracle corn).

Botanists have not yet been able to find the original wild forerunner of the first cultivated corn, which is believed to have grown in Mexico some ten thousand years ago. Its origin most likely goes back to a sudden mutation of teosinte, a grass native to Central America. Or perhaps it was as the Native Americans claim: that corn came down from heaven to earth as a goddess. Or, as the Ojibwa tell the story, corn came from other worlds as a green-clad stranger with yellow hair. When a young man on a vision quest wrestled the stranger and killed and buried him, the magical being came back to life as a corn plant.

Like a mighty deity, the corn plant conquered one tribe of people after the other. Its realm expanded to the north into Canada and south as far as Argentina; and wherever the corn deva appeared, people’s lives changed. Hunters and gatherers became sedentary; villages and even cities sprang up; elaborate irrigation systems, stately warehouses, and temples were built—solely for corn. Priests told myths surrounding corn and celebrated elaborate ceremonies. Even humans were sacrificed to the maize deity. Amerindians fattened turkeys with corn; Mexicans did the same with the Chihuahuas they bred for meat.

Illustration 30. Oldest European drawing of corn (Leonhart Fuchs, De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes, 1543)

According to the Popul Vuh, in the Mayan tradition the first human beings were made from corn mush. Primeval, divine male and female ancestor spirits created these “shining children of light” by grinding yellow and white ears of corn, which became their flesh and blood. Even the gods themselves got their strength from corn. Nahuatl lore tells how azcatl, the ant, once went on a pilgrimage to the mythical mountain of food. On the way, the ant met up with Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, who also took on ant shape. Together they carried corn from the mountain to give to the gods; that is how the gods got too be so strong.

The Arikara tell that in the beginning of time humans lived miserable lives in the dark depths underneath the surface of the earth. But the Corn Mother, who lived with the Great Spirit in the heavens, took pity on their misery. With the help of badgers and moles she dug into the earth’s surface and led the humans into the light of day. She then gave the first people corn to grow and then returned to the heavens. Unfortunately, humans turned out to be lazy, and constantly fought with each other. So the Corn Mother had to come down to earth again to teach them rituals and ceremonies so that they could live in harmony.

The Zuni tell that the Corn Mother planted a piece of her heart into the earth and that the sacred plant developed out of it. The goddess then explained, “This corn is my heart and shall be like milk from my breasts that you may not go hungry.”

The Cherokee and other forest peoples tell how in the beginning of time the corn goddess lived with her children, who were the first humans, in the forest. In order to feed her family she brought a basket of corn every day from an isolated hut. One day her curious children followed her to see where the delicious corn came from. They were shocked to find her turning into corncobs dirt that she rubbed from her belly and private parts. Convinced that she was a wicked witch, they killed and buried her. Out of her grave grew a reed-like plant that soon produced ears of corn. And so the children were able to eat their daily corn again, but now they had to work hard for it.

Over thousands of years Native American gardeners developed hundreds of different varieties of corn: varieties with white, yellow, red, and blue kernels; flint maize; starchy kernels or soft corn; dent corn, today used for feeding livestock; pearl corn, with delicate kernels; and the giant white corn of Cusco. Native women ground the corn and mixed in a bit of wood ash in order to make porridge, grits (hominy), or tortillas. Adding some ash is important because its alkaline nature helps the body make maximal use of the nutrients, especially niacin, calcium, and protein. (Since corn lacks the important amino acids tryptophan and lycine, it’s best eaten in combination with beans in order to avoid protein deficiency.)1

Native Americans have known popcorn for at least five thousand years. One of the gifts they gave to the pilgrims newly arrived in New England was popcorn in deer leather pouches. One of the favorite delicacies of the forest Indians was spoonfuls of corn mush cooked in sizzling bear fat and eaten with maple syrup; the white settlers named these fritters “hush puppies.”

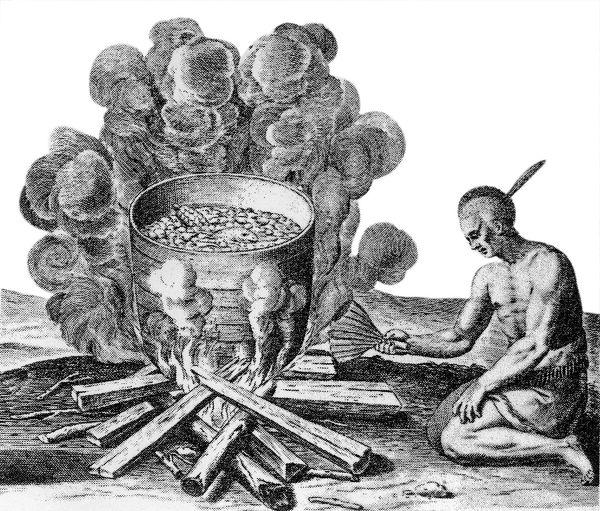

Illustration 31. Native Americans cooking soup with corn and fish (copper engraving from a painting by John White, “Indians Round a Fire,” 1590)

Central American natives make an inebriating and healthful corn beer, chicha. It’s made from women chewing corn kernels and spitting the resulting mash into a vat to let it ferment. Because corn has no malt in it like barley does, the amylase in saliva is needed to turn the starch to sugar.

Native Americans have always eaten corn on the cob, either boiled or roasted in the husk over a fire, but their original corn was not the sweet corn that we know today. Sweet corn seems to have originated about two hundred years ago from a mutation in the raised beds of the Iroquois. Due to the loss of a gene responsible for turning sugar into starch, the kernels remain sweet; but because they have so little starch, the kernels shrivel soon after ripening.

In a strange twist, the corn of today is completely dependent on human care in order to survive; the seeds are so tightly fixed that it could never sow itself out.

Healing Aspects of Maize

As one might expect, the sacred corn is also a healing plant. Similar to our European ancestors, who baked healing herbs into bread, Native Americans often administered their medicinal plants in corn mush. The Mayans said that a very sick person should eat nothing but pure corn mush, as this was the best way to create healthy flesh to replace the sick flesh. The patient would be literally recreated, much like the first human originally created from corn. Native American healers generally used hot corn mush poultices for swelling, abscesses, and infections. For slowly healing abscesses and heavy bleeding after birth, as well as for a bleeding uterus, corn kernels infected with corn smut (Ustilago maydis) were ground to a powder; this was used—very carefully dosed—as a vasoconstrictive means to stop bleeding.2 (In Europe midwives also very carefully used Claviceps purpurea, the ergot fungus that grows on rye, for similar purposes.) Native healers also made a very effective diuretic tea out of corn silk that they used for dropsy and genital and urinary diseases. Today corn silk tea is still used in Mexico for cleansing the urinary tract.

The Cultural Impact of Maize

Columbus brought “Indian wheat”—or “mahis,” as it is called in the language of the Caribbean Indians—to Europe. It spread from Andalusia over southern Europe, Turkey, and the Balkans. The Portuguese brought it to Java in as early as 1496. In the following century, corn was raised in China, India, and Africa on hillsides that were otherwise not well suited for conventional crops. Wherever it was cultivated, the novel plant triggered a population explosion, which in turn changed local lifestyle and culture. For example, after its introduction, the populations in Africa, Asia, and southern Europe doubled within a short time.3

The deva of the corn plant has proven to be a power house. With the help of advanced agricultural technology and an intensive energy input, the annual production of corn worldwide amounts to some 600 million tons (over 50 percent of that in the United States alone). As such, corn is well on its way to replacing wheat and rice as the most cultivated staple. El maíz is the “daily bread” in both Mexico and, indirectly, the United States, where it is the main feed for cattle, pigs, turkeys, and chickens. In America, both beer and bourbon are made primarily of corn. Starch, glucose, and cellulose from genetically engineered corn make up an important factor in chemical, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. Cornbread and a gargantuan corn-fed turkey are a must at every Thanksgiving feast. Even George Washington preferred cornbread to wheat bread.

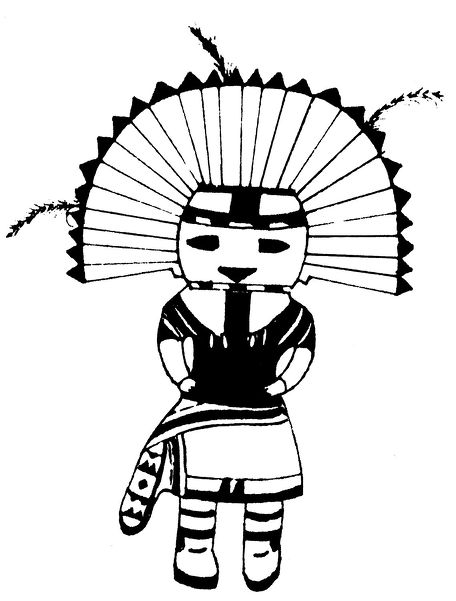

Illustration 32. Kachina doll—one of the Pueblo guardians of the cornfields

In contrast to the grain grasses of the old world—rice, rye, millet, wheat, barley, or oats—corn is much heavier and much more massive. The heavy spikes, or ears, are not poised gracefully on top of the stalk, but seem to slide down the stem as though pulled by gravity. It follows logically that corn is an appropriate symbol of material abundance or wealth. Because of this heaviness, and because corn comes from the West, the land of the setting sun, traditional European herbal astrologists attributed the vegetable to Saturn.4

Extensive monocultures of corn have changed our landscape; it’s also allowed us to wallow in mountains of meat, butter, and eggs. Popcorn, corn chips, corn oil, corn syrup, and canned corn have also transformed traditional European eating habits and way of life. It’s been a long time since Europeans wrinkled their noses at the corn in post-WWII American care packages, considering such “animal fodder.” Cornflakes—developed toward the end of the nineteenth century by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg as a “wellness food”; indeed, as part of an antisexuality campaign—have ousted most other breakfast flakes. It would appear the crispy, often sugarcoated flakes, next to Coca-Cola and hamburgers, make the most significant American contribution to “our daily bread” (Pollmer 1994, 111). In the wake of the Americanization of the globe, people worldwide are getting ever more used to enjoying Hollywood films with popcorn and corn syrup-sweetened soft drinks.

Lest you think I dislike this mighty American, know that corn has established itself firmly in my garden here in the foothills of the Alps. I sow this vital wind pollinator in a block instead of in single rows and fertilize it with good compost, as it is a heavy feeder. (The Iroquois stilled its hunger by putting a fish in each mound as fertilizer.) The corn patch thanks me for this good care by producing plenty of delicious sweet corn in the fall. The rule of the house is to not pick the corn for the meal until the water is already boiling—because the sugar turns to starch so quickly.

Despite the short summers in northern climates, corn can still thrive due to its accelerated photosynthesis, the so-called “turbo photosynthesis” or C4 carbon fixation, which utilizes carbon more efficiently than most plants do.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Sweet corn can be planted about the time of the last killing frost. For pollination to occur, which provides a full ear of corn, seeds should be planted in blocks rather than in rows. As soon as the plants are a few inches tall put on a good mulch to keep weeds at bay and protect the shallow roots from drying out or injury. If you do not want your corn to come in all at once, plant one-fourth of it every week for four weeks. (LB)

SOIL: Corn needs a lot of nitrogen, so work plenty of compost into the soil before planting.

Recipe

Corn Soup à la Paul Silas Pfyl ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1½ pounds (680 grams) fresh corn kernels ✵ 2 tablespoons butter ✵ 3 tablespoons paprika powder ✵ 1 tablespoon honey ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) cream (18% fat) ✵ black pepper ✵ chili pepper (optional)

Sauté corn kernels in butter in a medium pan. Add paprika powder and honey and mix well. Add broth and simmer for 20 minutes. Purée the soup with a blender. Add the cream and pepper to taste. Serve hot.

TIP: This soup pairs nicely with flat bread.