A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Cabbage Family (Brassica oleracea)

Plant Family: Brassicaceae or Cruciferae: mustard family

Other Names and Varieties: chou, cole, colewort, green cabbage, kale, karam kala, purple cabbage, red cabbage, repollo, vitamin U (S-Methylmethionine), white cabbage

Family Includes: broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, Chinese cabbage, pointed cabbage, Savoy cabbage, collard greens, kale

Healing Properties:

TAKEN EXTERNALLY: fresh leaf poultices help heal abscesses, burns, neuralgia, onychia, phlegmon, rubella/German measles, shingles/herpes zoster, tumors, uterus infection, persistent wounds

TAKEN INTERNALLY: cabbage juice soothes stomach and duodenal ulcers, prevents gall bladder infection; sauerkraut juice reduces arteriosclerosis, cleanses blood, detoxifies body, strengthens immune system, regulates intestinal flora

Symbolic Meaning: dullness; excessive vitality, Jupiter-like abundance; opponent of drunken Dionysus; St. Bartholomew

Planetary affiliation: moon and Jupiter; SHARP-TASTING SEEDS AND RED CABBAGE: Mars; SAVOY CABBAGE: Mercury

The wild form of cabbage still grows as a thick-leafed plant along the coasts of the Mediterranean and the North Sea. On the island Helgoland in the North Sea, which was a sacred place for the Vikings, wild cabbage especially displays its natural beauty. A wax-like layer protects the fleshy leaves from salty fog, and biting frosts. The cold-resistant mustard oil glycosides prevent winter ocean winds from harming the plant. The beautiful flowers are as yellow as sulfur.

Stone Age hunters cherished the nourishing leaves as a vegetable and the seeds for oil. It’s an “anthropochore” vegetable—meaning it is distributed by humans, whether deliberately or accidentally. Wild cabbage found a perfect niche growing as a weed on the trampled and bare soils near human settlements fertilized with nitrogenous waste, such as food leftovers and the urine and feces of humans and animals. Gardeners gradually experimented with the plant until there were many variations—from pot-bellied kohlrabi to tree cabbage, which can grow up to seven feet tall. Pointed cabbage, Savoy cabbage, red cabbage, white cabbage, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, cauliflower, and kale all belong to the same species: Brassica oleracea. Mild, pale Chinese cabbage (B. pekinensis), the robust bok choy or pak choi (B. chiniensis), and turnips (B. rapa) are closely related, as they belong to the same genus.

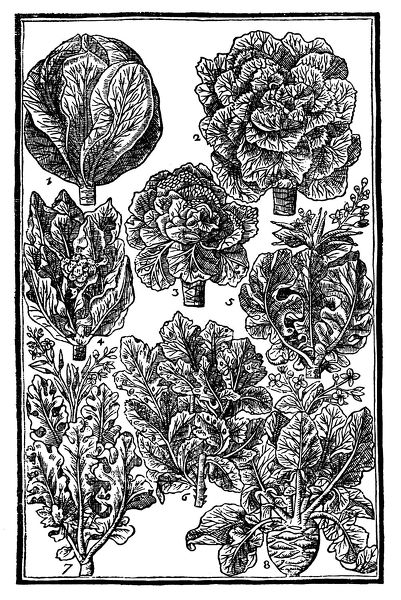

Illustration 18. The many forms of cabbage (John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1629)

Cabbage is, so to speak, the dog amidst the vegetables. Like no other animal, dogs have let themselves be tamed, trained, and bred into various shapes and sizes—from the Chihuahua to the Great Dane—by meddling humans; the same can be said of cabbage. Celtic peasants in central Europe took special care to cultivate the wild plant into a vegetable staple. As such, almost all the names for this plant are of Celtic origin: kol, kal, kap, or bresic—which became the Latin word “brassica.” The Celtic names later traveled all the way to Asia; the Tatars call cabbage “kapsta”; in Hindu lands, it’s called “kopi” or “ghobi.” Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) first brought cabbage to the Americas circa 1541. Though there is no written record until the mid-seventeenth century, it can be assumed that both the settlers and Native Americans planted cabbage, as eighteenth century records indicate its cultivation in both cultures. Cabbage seeds came to Australia in 1788, where they were planted on Norfolk Island. By the 1830s it had become an Australian favorite.

Cabbage was a sacred plant to the ancient Greeks. According to Greek myth, when Zeus heard an ambiguous oracle he’d start to perspire; cabbage was formed from his beads of sweat. Given this nature, oaths could be sworn on cabbage, and keeping cabbage in bed kept bad spirits from children and birthing mothers.

Another legend from antiquity tells that the vegetable emerged from the tears cried by King Lycurgus. As the king disdained Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy, he chased ecstatic wine drinkers off his land and had the vineyards chopped down. In retaliation, Dionysus struck him with a madness that brought the king to a miserable plight; seeing grape vines everywhere, he cut the head off his own son and the foot off his own leg. The myth illustrates that, though cabbage makes the head dull, it also helps sober indulgence in wine; indeed, the Romans believed that cabbage can prevent drunkenness.

Cato the Elder (234-149 BC), who deemed cabbage the best medicinal plant there is, wrote: “Whoever wants to eat and drink a lot at a festival should eat raw cabbage with some vinegar first—then he can drink as much as he wants.” Cato’s fellow countryman, Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) claims that, thanks to cabbage, the Romans did not need doctors for six hundred years, as during this period people healed everything with cabbage—a tradition that lasted until Rome became decadent and people got soft, a situation clever Greek doctors, with expensive medications, took advantage of.

Although the German Benedictine abbess and plant enthusiast Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) wrote of both red and white cabbage, modern cabbage varieties did not appear in Europe until the Middle Ages when the round head cabbage was cultivated in northern Europe. Slavic peoples in central Europe invented sauerkraut, which involves the lactic acid fermentation of the shredded leaves; previously the Romans had preserved the whole leaves in vinegar without shredding them. Crinkly Savoy cabbage was cultivated in the seventeenth century in Savoy, France; through plant breeding northern Italian gardeners created cauliflower and broccoli; and in eighteenth-century Belgium, Brussels sprouts made their first appearance.

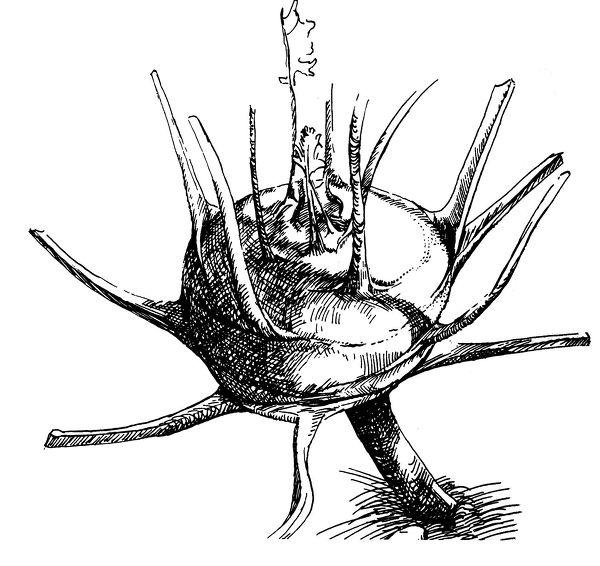

Illustration 19. Cabbage head cut in half (illustration by Molly Conner-Ogorzaly, from B. B. Simpson and M. Conner-Ogorzaly, Economic Botany, 1986, 225)

Though today cabbage is grown across the globe, it thrives especially well in the cool, moist northern Atlantic climate of central and northern Europe—indeed, where cabbage first appeared in its wild form. For many in central and eastern Europe—including the Dutch, Alsatians, Polish, Russians, and Germans—cabbage, next to porridge and bread, is a daily necessity, whether eaten fresh in the summer and fall or as sauerkraut in winter. As a result, cabbage came to be known as food for the simple peasants, as well as for simpletons. To this day English speakers call Germans “Krauts” because they eat so much cabbage. (The name of the rather overweight German chancellor Helmut Kohl could be translated as “Chancellor Cabbage.”) The pejorative French term for Germans, “les boches,” is a shortened version of the old French word “caboche,” which means knucklehead—though in Middle French caboche was simply a head of cabbage. (Indeed, the word “cabbage” derives from caboche.) Interestingly, though, the French also have a term of endearment concerning the popular vegetable: “mon petit chou” (my little cabbage).

Traditional and Modern Healing Use of Cabbage

The first time I had anything to do with the healing aspect of cabbage, I was working in a biodynamic garden near Geneva, Switzerland. Every day a family came to get fresh organic Savoy cabbage leaves for their grandfather who suffered from skin cancer. They assured me there was not a better healing plant. The fresh cabbage leaves are bruised with a rolling pin until they are malleable like cloth and then applied to the skin. This is done for abscesses, abrasions, burns, gout, herpes zoster (shingles), necrosis, onychia, pox, neuralgia, scabs, tumors—even just wounds that are not healing well. The wounds are freshly wrapped twice a day with the crushed leaves, cleansed in between with chamomile tea. And though this is, indeed, an ancient cure, modern naturopaths assure us it’s very sound treatment. The well-known Swiss medical doctor, Dr. Jürg Reinhard, still prescribes cabbage poultices to draw pus out of wounds, as well as cabbage leaves put on the abdomen for infertility or to counter the effects of long-term use of birth control pills. Famous herbal healer Maurice Mességué calls cabbage a “big, generous king” (roi du jardin potager), and “the apothecary for the poor.” With a chuckle he says, “Cabbage soup can (almost) resurrect the dead.” He also recommends crushed cabbage leaves for all kinds of ailments, such as hot crushed-leaf poultices for rheumatism and aching muscles, and cabbage juice for blood cleansing and liver and intestinal complaints. In traditional folk medicine, even the urine produced after eating cabbage is considered to have healing power. Renaissance doctor Hieronymus Bock (1498-1554) wrote that abscesses heal if they are bathed in the urine produced after eating red cabbage. For a hangover he recommends breathing in the steam from cooked cabbage.

Illustration 20. Kohlrabi, one of the many kinds of cabbage

In earlier times, scurvy was an awful winter plague, and one of the main benefits of eating cabbage or sauerkraut was how it kept scurvy at bay; the wonderful vegetable has even more vitamin C than do oranges. (Vitamin C is also an excellent antioxidant.) For this reason cabbage was a favorite winter food, and Christmas and New Year meals included it in ceremonial contexts. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as Dutch seafarers always had barrels of sauerkraut on their ships, they didn’t lose sailors due to scurvy as other sea powers did. The British, in particular, lost many sailors to scurvy; it was considered a miracle that Captain Cook lost no men on his three-year voyage. This was because the respected German scientist and explorer Georg Forster (1754-1794), who accompanied Cook, recommended he bring sixty kegs of sauerkraut for the crew. Any sailor who did not want to eat it could reckon with a flogging.

Though its various active ingredients contribute to the healthful effect of the cabbage, it’s also the incredible vitality of the plant that makes this heal-all vegetable such a potent medicine. According to Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) cabbage leaves, especially when crushed, radiate vital energies or “etheric formative forces” (Bildekräfte), which are taken up by ailing tissue in a way similar to fresh cell therapy. This corresponds to the folkloric belief held in France, Belgium, and parts of Germany that mothers receive their babies from the cabbage patch, for the plant is a wellspring of vitality and energy.

Cabbage Magic

In Europe, this important food and medicinal plant is surrounded by more magical folklore and taboos than most other plants. Many gardeners sow or plant on main Christian holidays, such as either Good Friday, Maundy (Holy) Thursday, or the day of a major saint—for example, March 17, the day of St. Gertrude, patroness of gardeners, better known as St. Patrick’s Day. Gardeners believe they should sow when the church bells are ringing so the heads grow as big as the bells; or when the moon is waxing so the “heads will grow big and round.” A sizable boulder was sometimes placed in the garden bed to inspire the cabbages to “become this large and firm.” And as she planted cabbage seedlings the farmer’s wife should say, “Heads like mine! Leaves like my apron! Stalks like the top of my thighs!” It was also seen as auspicious if a pregnant woman planted the seedlings, so the cabbage would grow fecund and round by her example.

Similarly, some days are not good for planting, such as April Fool’s Day (April 1), because—“they will turn into fools” (meaning the crop will be worthless). Days when the moon was in an inauspicious zodiac sign were also avoided. With a moon in Sagittarius “the growing energy will shoot into the leaves”; in Capricorn the cabbage “will be hard and woody”; in Cancer “worms will gnaw away the roots.” One was also careful about which day one made sauerkraut: if the moon was in the sign of Pisces, the kraut would become slimy, like fish.

The seeds themselves were put in holy water before sowing, or in the ashes from Ash Wednesday fires. And as they planted the seedlings men and women would joke, throw sod at each other, or try to bowl each other over—all behaviors remnant of the ancient sympathetic magic practice of performing coitus in the fields in order to increase fertility in nature.

To keep worms out of the cabbage patch, words of blessing would be spoken while sprinkling on the plants holy water from springs named after St. Peter. (Following Christianization, St. Peter took the place of Donar/Thor, the weather god, who fought lindworms and dragons with his hammer.) If caterpillars were devastating the crop, the peasant wife walked naked around the patch at midnight chanting sayings like: “There’s a fair in town, young ladies; off to the fair!”

St. Bartholomew, the beheaded saint, was the patron of the cabbage. On St. Bartholomew’s Day (August 24), no one was allowed to go into the cabbage patch because they would chase off “old Barthel,” who on that blessed day was busy making the heads solid and big. No one was allowed in the cabbage patch on the day of St. Gall (October 16) either, because that would make the cabbage as bitter as bile from the gall bladder. By contrast, walking through the garden on St. John’s Day would encourage the cabbages to grow big. On St. Jacob’s Day (July 25), the gardeners called out to the cabbages, “Jacob, you bull head, let the cabbages be as big as my head!” (Jakob, du Dickkopp, Häupter wie mein Kopp!) And on St. Stephan’s Day (December 26), instead of being eaten, cabbage was honored—because the saint had hidden in a cabbage patch in order to escape capture.

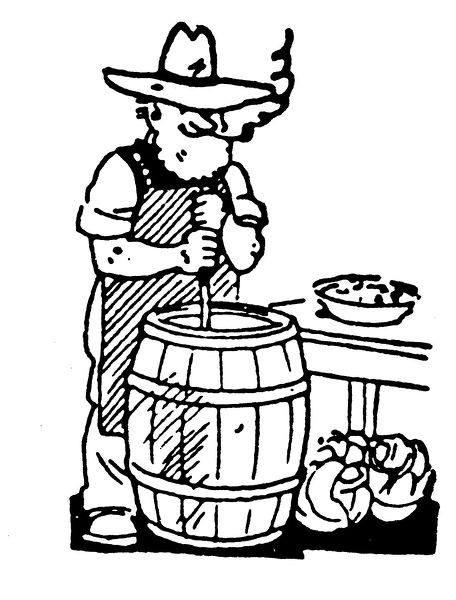

Illustration 21. Making sauerkraut (illustration/woodcut by K. Paessler, Gärtner Pötschkes Großes Gartenbuch. 1945)

With the decline of country ways in the last century, unfortunately, these magical customs died out—and with them the healing virtues of cabbage were mostly forgotten. New research, however, confirms traditional old healing knowledge regarding cabbage. Modern medicine recognizes cabbage, freshly juiced or eaten raw, as a helpful treatment for stomach and duodenal ulcers. Sauerkraut—best eaten raw—is ideal nourishment to counter ailments caused by overly acidic foods containing too much protein and sugar. And sauerkraut juice is one of the best drinks for health; it detoxifies, improves bowl movement, strengthens the immune system, lessens arteriosclerosis, balances out the intestinal flora, and provides ample quantities of vitamin C.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Start seeds indoors six weeks before transplanting time, which is after the danger of heavy frost is past. Early varieties must be picked while they are firm so be sure to harvest before midsummer heat forces a seed head to form. Late varieties require much longer to mature and will benefit from a light fall frost, which enhances the flavor. (LB)

SOIL: Few plants feed more heavily than those in the cabbage family. For best results, work aged compost at least eight inches into the ground, as the roots can grow down to three feet or more. In sandy soil they also need plenty of water, so soak the ground around them thoroughly. During the growing season give the plants a few applications of compost tea.

Recipes

Amaranth on Grated White Cabbage with Thyme ✵ 4 SERVINGS

2 ounces (60 grams) amaranth seeds ✵ 2 cups (455 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ 1 tablespoon paprika (or to taste) ✵ 1 teaspoon thyme leaves ✵ 4 teaspoons olive oil ✵ 1¼ cup (285 grams) white cabbage, finely chopped or grated ✵ 4 tablespoons mayonnaise ✵ 1 tablespoon honey ✵ 3 tablespoons raisins ✵ 1 teaspoon apple vinegar ✵ 1 pinch cinnamon ✵ herbal salt ✵ white pepper ✵ 2 tablespoons alfalfa sprouts

Pour the vegetable broth into a medium sauce pan. Add the amaranth seeds and simmer gently, covered, over medium heat for about 15 minutes or until the grains are fluffy and the water is absorbed. Add paprika to taste. In a separate pan, sauté the thyme in 1 teaspoon of the olive oil until crispy; mix into the broth. Place the cabbage in a medium bowl. Stir in the mayonnaise, honey, raisins, remaining tablespoon of olive oil, and apple vinegar and mix well. Add the cinnamon; add the herbal salt and pepper to taste. Serve the cabbage salad garnished with the alfalfa sprouts, with the amaranth (it should be lukewarm) on the side.

Barley Soup with Sauerkraut and Yogurt ✵ 4 SERVINGS

5 tablespoons whole wheat barley, soaked overnight ✵ 5 tablespoons sauerkraut, finely chopped ✵ 2 bay leaves ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 5 cups (1¼ liters) vegetable broth ✵ ground coriander seeds ✵ herbal salt ✵ black pepper ✵ 4 tablespoons plain yogurt ✵ a bit of fresh lovage, finely chopped

Sauté the barley, sauerkraut, and bay leaves in olive oil in a large pan. Add the vegetable broth and simmer until barley is tender. Add the coriander seeds; add herbal salt and pepper to taste. Transfer to a serving bowl. Stir the lovage into the yogurt; serve it with the soup.

Baked Red Cabbage with Whipped Rosemary-Sesame Sauce ✵ 4 SERVINGS

CABBAGE: 2 pounds (905 grams) red cabbage, finely chopped ✵ 1 bay leaf ✵ 1 clove ✵ 1 small cinnamon stick ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ 1 egg, plus 2 egg yolks, whisked together ✵ a splash of cream ✵ SAUCE: 2 twigs of fresh rosemary ✵ 3 tablespoons sesame seeds ✵ 1 tablespoon olive oil ✵ 2 heaping tablespoons cottage cheese (pressed through a sieve); or cream cheese ✵ freshly ground horseradish, to taste ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper

CABBAGE: In a large pan simmer the cabbage with the bay leaf, clove, and cinnamon stick in the vegetable broth until the cabbage is tender and the pan is dry. Let cool for 15 minutes Mix in whisked egg mixture and cream. Transfer into an ovenproof form and bake at 300 °F (~150 °C) for 30 minutes or until firm and golden on top. done.

SAUCE: Sauté rosemary and sesame seeds in olive oil. Season to taste with herbal salt and pepper. Let cool. Mix in cottage cheese and horseradish. Serve with the red cabbage.

White Cabbage (or Collard Greens) with Mustard and Caraway ✵ 4 SERVINGS

4 tablespoons butter ✵ 1 tablespoon caraway ✵ 2 tablespoons black peppercorns ✵ 1 pound (455 grams) white cabbage (or collard greens), finely chopped ✵ 1 cup (225 grams) potatoes, peeled or unpeeled, cubed ✵ ¾ cup (175 milliliters) white wine ✵ 1 cup vegetable broth ✵ 1 tablespoon honey ✵ sea salt ✵ black pepper ✵ 4 tablespoons sour cream

Sauté the caraway and peppercorns in the butter in a medium pan. Add the collard greens and potatoes and continue to cook. Once the ingredients are well sautéed, add the white wine and vegetable broth; simmer until the greens and potatoes are tender. Add honey; add sea salt and pepper to taste. Let stand covered for 2 hours. When ready to serve, reheat and serve with sour cream.