A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Forgotten, Rare, and Hardly Known Lettuce Greens

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

Family: Portulacaceae: purslane family

Other Names: little hogweed, moss rose, little pigweed, pursley, pressley, red root, verdolaga

Healing Properties: cools fever and inflammation, stimulates circulation and regulates heart function, strengthens immune system

Symbolic Meaning: marriage, bonding of opposites (language of flowers)

Planetary Affiliation: moon, Mercury

The hot continental summer climate such as is found in the American Midwest—where I spent most of my childhood—is a perfect place for purslane to grow wild. Indeed, the delicate but extremely vital plant used to overgrow the ground in the cornfields to the extent that the farmers scornfully called it “pigweed.” The Amish who live in that same area called it “meisdreck” (mouse filth). In those preherbicide days, kids could earn some pocket money by helping hoe the cornfields in order to hopefully rid them of this competing vegetation. No one seemed to know back then that the plant is edible and that it is actually a humus-protecting natural ground cover. No one seemed to know, either, that the seeds of the hacked-off plants continue to ripen and can go on to germinate despite the disruption.

Many years later I had the pleasure of enjoying a vacation in Greece. One day I ordered a salad and was astonished to see a plate of nicely chopped purslane with tomatoes and onions—dressed with olive oil, lemon juice, and sweet basil. It was absolutely delicious. Somewhat later, I was even more surprised to find cultivated purslane (considerably larger than the wild plant) in a French garden. It was called “pourpier doré,” and the gardener told me that it’s popular in soups and salads; purslane and sorrel (oreille) are ingredients in a soup called “bonne femme” (good woman) in France. Eventually I realized that purslane is very much liked as a vegetable all over the world.

This juicy plant, with its succulent, round leaves and thick, fleshy stems, is a true cosmopolitan. It blossoms modestly with small yellow flowers and has black seeds that ants carry away, thus distributing the plant. It grows wild in South Africa, where it is called “women’s food,” as well as in Southern Asia, where it is cultivated and sold in markets. In the Near East it is an ingredient in a mixed salad called “fattoush.” In Mexico it is called “verdolaga,” and is used in salads and soups; in China it is sautéed in sesame oil with bean sprouts in a wok. Purslane is generally recognized as cooling and thirst quenching, and thus helpful in calming a hot temper. Ancient Greeks and Romans knew it as both an edible plant and a healing one. Dioscorides (~40-90 AD), who called the plant “andrachni,” recommended the leaves for headache, heartburn, and kidney and bladder ailments; he noted the juice soothes the eyes. Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) derived forty-five remedies from purslane; Galen (129-~216 AD) considered it nearly a heal-all plant. Pliny wrote that just wearing an amulet with the plant would ward off all kinds of evil. Purslane’s generic name “portulaca” comes from the Romans, derived from the Latin portula, meaning “small door”—likely a reference to how the seed capsule opens like a door when the seeds are ripe.

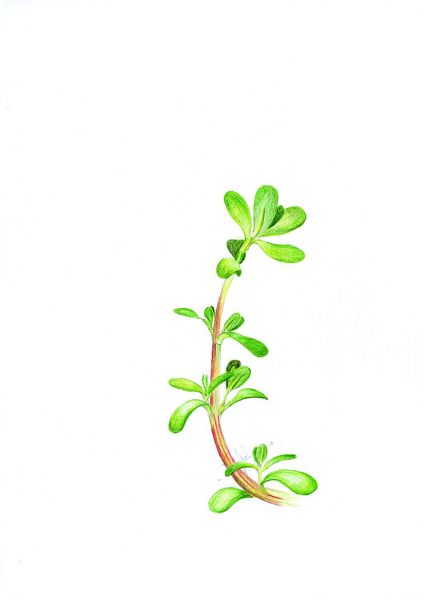

Illustration 102. Tender purslane leaves

Purslane came to northern Europe with the Romans. The earliest seed findings in northern Europe were discovered in Neuss on the Rhine. The plant can still be found growing wild in the Rhine region in gardens, potato fields, and asparagus fields (Koeber-Grohe 1987, 296). Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) was the first to write about it, as “burtel” or “Portulaca,” though she saw little virtue in this “cold and slimy” plant. Wolfram von Eschenbach, the twelfth-century troubadour, wrote that the knight Gawain liked to eat it. But, in general, it seems that the northern Europeans did not find the plant very interesting. This changed, however, in the sixteenth century, when it became popular in salads.

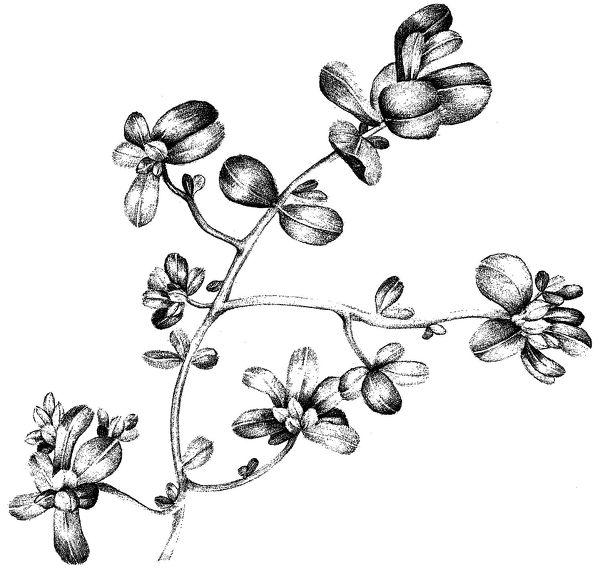

Illustration 103. The Romans brought purslane to all their colonies

Famous German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566) elaborated on the plant: “It is moist to the third degree; mixed with barley flour and used as a poultice on the head, it reduces heat and also helps inflamed, red eyes; it can be chewed to help with a toothache; it helps damaged bladders and kidneys; to alleviate a sunstroke, one can mix the juice with rose oil and rub it into the head.” He also mentioned that purslane can be pickled (like olives or capers) and that, added as a green to salads, “it strengthens the stomach.” A century later, Nicholas Culpeper put it under the rule of the moon because of its “cooling properties”—countering the damaging hot, negative aspect of Mars. He prescribed drinking the juice for a dry cough and applying it topically for fever and inflammations.

As mentioned earlier, Americans did not show much enthusiasm for the plant. For example, in his 1821 publication American Gardener, farmer and journalist William Cobbett described it as “a mischievous weed that Frenchmen and pigs eat when they can get nothing else. Both use it in salad, that is to say, raw” (Cobbett 1856, 157). But, fortunately for purslane, times change. In the 1980s it gained notoriety—alongside mineral water, muesli, and yogurt—as part of fresh, healthy approach to life.

Purslane presumably originated in South Asia; later it spanned the globe. Research shows that the plant (called “khursa” in Hindi) has been cultivated in India for thousands of years, where it is also used as a healing plant for liver, spleen, kidney, and bladder ailments. It remains unclear how the plant reached America. Samuel Champlain, who was active in the French colonization of Canada, reported from a trip to Maine (1604-1610) that purslane grew under the corn but that the natives didn’t use it. But ethnobotanists disagree, noting that the Native Americans used purslane as both a vegetable and as a healing plant; they gathered the edible seeds and dried the leaves for winter use. (I posit that perhaps Champlain did not correctly identify the weed on the corn mounds.) The Cherokee used fresh purslane juice for earaches. The Iroquois put fresh juice on burns and bruises, and drank it as an antidote to “bad medicine.” For the Navaho the plant is basically a heal-all for just about any sickness; for scarlet fever, they rub the whole body with the juice (Moerman 1999, 434).

Purslane abounds with vitality; it contains many minerals (magnesium, potassium, phosphor, and iron) and vitamins, especially vitamin C (18-25 mg), vitamins B1 and B6, and carotene. The leaves’ refreshing flavor comes from omega-3 alpha-linolenic acids, which are also present in fish oil and cod liver oil; in purslane, however, they also taste good. It has a positive effect on the heart and circulatory system, and strengthens the immune system.

The seeds are also edible. They can be cooked in mush or added to bread flour or mixed in with cereals. A good way to harvest the seeds is to cut the capsules from the plant and let them dry in a paper bag; when they are dry, shake the bag until the seeds all fall out of the capsules. The fleshy stems and leaves are good in soups and salads, and can also be preserved in vinegar like capers.

Very little is known about the symbolism of the plant. An old German herbal book reads: “Even though purslane is cold and moist, it is a real summer plant and does not like the cold. There is a saying that in marriage it is always good when two different temperaments join together. The good Lord alone knows what is best and for that reason sometimes two very different personalities join together in marriage” (Axtelmeier 1715). Accordingly, purslane is a good symbol of marriage.

Recipe

Purslane Salad with Red Currants ✵ 2 SERVINGS

1 cup (225 grams) purslane ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) red currants ✵ ¼ cup (50 grams) parsley, finely chopped ✵ DRESSING: 2 tablespoons vinegar (red currant, red wine, or balsamic) ✵ 4 tablespoons sesame oil ✵ 1 pinch cinnamon ✵ 1 teaspoon turmeric ✵ 2 tablespoons Parmesan cheese, grated ✵ herbal salt ✵ white pepper

Gently combine the purslane and berries in a serving bowl. In a separate small bowl, mix the vinegar, sesame oil, cinnamon, turmeric, and grated Parmesan. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Drizzle the dressing over the salad and toss gently.