A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Forgotten, Rare, and Hardly Known Lettuce Greens

Mustard Greens (white mustard: Sinapis alba, black mustard: S. nigra, Brassica nigra, Indian mustard: B. juncea, wild mustard: S. arvensis)

Family: Brassicaceae or Cruciferae: crucifer or cabbage family

Other Names: bamboo mustard cabbage, Chinese mustard, Indian mustard, leaf mustard, mizuna, mustard cabbage, sow cabbage

Healing Properties: MUSTARD FLOUR (SEEDS): externally: poultice eases bronchitis, soothes and warms lumbago, sore muscles, rheumatism; soothes inflamed joints; internally: stimulates circulation, warms the skin, induces vomiting (emetic); MUSTARD OIL: internally: kills parasites (antiparasitic); externally: fights fungal infections, eases eczema and hives, stimulates hair growth

Symbolic Meaning: heaven, spiritual imagination, alchemical lion, drives off demons, matriarchy (petticoat government), idle talk; Agni, Shiva

Planetary Affiliation: Mars, sun, Jupiter

There are several kinds of wild and cultivated mustard greens with similar culinary uses. In northern climates they can be found growing wild along waysides and near dumps or other fallow areas. Mustard, which is closely related to rapeseed and rocket, is an annual with sulfur-yellow flowers and spicy, round seeds that ripen in pods. All mustard plants are edible.

Mustard grew as a weed companion in the flax fields of early Neolithic cultivators; over time it became an important cultivated plant. While Celtic and Germanic tribes knew the leaves as a vegetable, it was not until the Romans came that they learned to use the seeds as seasoning, The Romans macerated ground black and white mustard seeds in cider (called “mostum”), using the paste to help digest protein-rich meals. This was the beginning of what we today know as mustard, and today it still helps us digest protein, often in the form of frankfurters, hamburgers, and other grilled meat. It was the western Slavic peoples who came up with the idea of using mustard seeds in pickling brine.

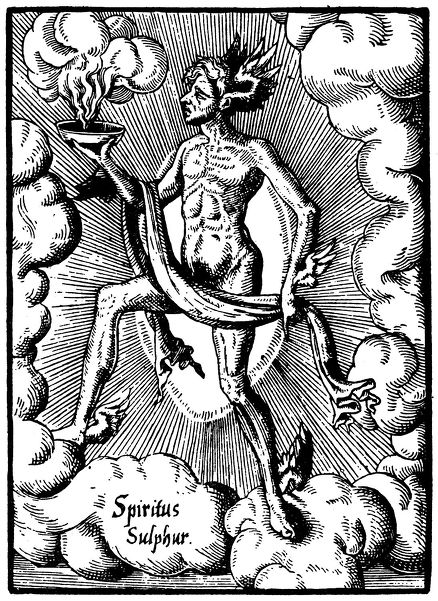

Illustration 100. Sulfur, the spirit in mustard (Leonhard Thurneysser, Quinta Essentia. 1574)

The appetizing young leaves and tender buds are very good in green salads. They are also rich in proteins, provitamin A, vitamin B, and C, as well as mineral salts (Couplan 1997, 30). White mustard leaves are milder, and black mustard is mainly grown for the seed. Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) has especially big leaves; it developed a very long time ago in northwestern India out of a cross between wild mustard (B. arvensis) and black mustard (B. nigra). This variety, commonly sold in markets in China and India, is eaten like spinach. It can also be cultivated very well in northern climates in the West. In order to always have some fresh greens, it’s wise to sow them out in two-week intervals in spring and fall. They need to be thinned out well in order to develop to full size.

The leaves also taste good on sandwiches or as Japanese tempura: dredged in beer batter, deep-fried, and seasoned with soy sauce. John Evelyn (1620-1706)—a great English garden enthusiast and green salad fanatic, who wished to guide humanity back to healthful and primal nourishment—persuaded the royal gardener to plant seventy different greens. In his 1699 publication Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets, perhaps our first book on salads, he wrote the following: “Mustard, especially in young seedling plants, is of incomparable effect to quicken and revive the spirits, strengthening the memory, expelling heaviness … besides being an approved antiscorbutic.”

Mustard has long been an essential ingredient in the kitchens of India, where it is called “rái.” It was mentioned in as early as 500 BC as a spice and vegetable in the Acaranga Sutra. Mustard, regarded as “hot,” is thought to strengthen the inner fire (agní) and open and cleanse the subtle “canals” (srota). For these warming and strengthening effects a lot of mustard is eaten in the winter months. And the poor fry food in mustard oil instead of the more expensive ghee, clarified butter; since mainly the poor use it, mustard falls into the tamasic category. As such, the offerings made for the dark (tamasic) god Shiva and his cohorts are prepared in mustard oil and seasoned with bitter neem leaves. This is because, according to the Indian mindset, one cannot detach the food one eats from mood and character. By contrast, offerings to Vishnu are made with butter and are sweet, as the god is full of light and has a sattvic character (Achaya 1998, 131).

But in Western esotericism and alchemy, mustard was seen as anything but dark and lowly. With its deep-yellow blossoms it was regarded as a bearer of light and fire, as sulfur in plant form and as a “sun bearer” (from the Latin sol = sun, ferre = carry). For these mystics sulfur is “fire of the earth” (ignis terrae), it is the saving light of Christ that descended down into matter. Even Jesus likened the kingdom of heaven to a mustard seed:

The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed which a man took and sowed in his field; it is the smallest of all seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches (Matthew 13:31-32)

Mustard was the last of the thirty-eight flower essences discovered by Edward Bach (1886-1936). He recommended it for psychic distress that comes from the deepest parts of the soul, when depression and sadness well up from the depth of the unconscious. Bach wrote that mustard drives off depression and restores the joy of life. Without this sulfur power, without the inner sun, people can easily sink into black depths.

Because of its sharpness, Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) put mustard under the rule of Mars. He prescribed ground mustard seeds mixed with honey and rolled into small pills taken on an empty stomach in the morning, or rubbed into the temples and under the nose to “warm and enliven the spirit.” Other astrological herbal healers saw the sun as the ruler of the yellow blossoming, spicy plant; but, due to its effect on the digestion, it is from a Jupiter-influenced sun.

In both European and Asian healing lore, the seeds are a very important healing agent, especially when ground into mustard flour. The plant contains mustard glycosides that when mixed with warm water separate and develop both extreme pungency and an antibacterial effect. Apparently Hippocrates (460-370 BC), the “father of natural healing,” used the pungent black mustard in this way. A poultice of mustard flour draws the blood to the skin’s surface to deeply heat the tissue. (It can even burn the skin if not correctly applied.) Freshly ground seeds are mixed with water and made into a poultice (rye flour is added to make it milder), then applied to the ailing area. Mustard poultices are used for acute inflammation in the joints, rheumatism, sciatica, muscle pain, pneumonia, pleurisy, and lumbago. A mustard flour poultice can also be placed on the lower abdomen for chronic constipation. To induce vomiting, one teaspoon of mustard flour mixed with water is useful in cases of poisoning and intoxication. Mustard oil can be rubbed into the skin as an antiparasitic for fungi infections, hives, and eczema.

Mustard was also used magically. It was thought that whoever eats mustard seeds on an empty stomach in the morning ensures against suffering a stroke. And whichever woman wants to rule the roost in marriage is advised to secretly carry mustard seeds and dill to the wedding ceremony. While the servant of God speaks the solemn words, she should quietly whisper: “I have mustard and dill; man, when I talk, you remain still!”

In Indian lore, mustard, and especially mustard seeds, play a major role as demon expellers. Mustard seeds and other plants are censed (ritually burned) for the protection of newborns; the mother’s first bath after giving birth is prepared with some mustard seeds. During funerals or shraddha—ceremonies for feeding the spirits of the dead—participants rub mustard oil into the palms and soles of their feet. Mustard oil cooked in henna leaves is a favored hair oil; massaged into the scalp, it is believed to encourage hair growth.

There are a lot of expressions in northern Europe involving mustard. In Germany, to give one’s two cents’ worth is called “to give one’s mustard” (seinen Senf dazugeben); if someone is told to not dramatize a situation, one says, “Don’t make mustard out of it” (Mach keinen Senf daraus). In Germany, Holland, and France, when things get out of hand and the jokes get too coarse, one says, “This mustard bites the nose.” In Holland mothers sometimes wean their babies by putting some mustard on their nipples—therefore, when someone wants to ruin something for someone else, they “put some mustard on the teat.” And of course there are some English expressions too, such as “as keen as mustard,” “the proper mustard” (the genuine article), and “doesn’t cut the mustard.”

Recipe

Mustard Greens Lasagna with Sauerkraut and Horseradish ✵ 4 SERVINGS

FILLING: ½ cup (115 grams) white or yellow onion, chopped ✵ 1 tablespoon olive oil ✵ 1 teaspoon honey ✵ 1 heaping cup (250 grams) sauerkraut, finely chopped ✵ herbal salt ✵ SAUCE: 3½ cups (800 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ 1 cup (225 milliliters) white wine ✵ 4 bay leaves ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) cream (18%) ✵ 5 tablespoons lentil flour ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ LASAGNA: 12 fresh green lasagna noodles ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) mustard greens ✵ 2 tablespoons (40 grams) pine needles, finely chopped or 20 juniper seeds ✵ 1 tablespoon horseradish ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) cheddar cheese, grated

FILLING: In a medium pan, gently sauté the onions in the olive oil until glassy, about 10 minutes. Add the honey, sauerkraut and horseradish and sauté another 5 minutes until very well blended. Remove from the heat and let cool. Season with salt to taste.

SAUCE: Pour the vegetable broth and white wine into a large pot. Bring to a boil. Add the bay leaves and cook for 10 minutes. Add the cream and lentil flour to bind slightly. Season with nutmeg to taste and set aside.

LASAGNA: Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Put 1 layer of lasagna noodles into a large ovenproof dish. Arrange one-third of the mustard greens in an even layer on the noodles. Arrange one-third of the sauerkraut in an even layer on the greens. Add one-third of the sauce in an even layer on the sauerkraut. Repeat with the remaining quantities of noodles, greens, sauerkraut, and sauce. Arrange the pine needles on the last layer of sauerkraut. Finish with the last bit of sauce and the grated cheese. Bake at 350 °F (175 °C) for 1 hour. Serve warm.