A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Forgotten, Rare, and Less-Known Vegetables

Knotroot or Chinese Artichoke (Stachys sieboldii, S. tubifera, S. affinis)

Family: Labiatae or Lamiaceae: mint or deadnettle family

Other Names: artichoke betony, Chinese artichoke, crosne, Japanese potato

Healing Properties:

TAKEN EXTERNALLY (TEA): heals wounds

TAKEN INTERNALLY: general health tonic

Symbolic Meaning: wards off witches

Planetary Affiliation: AS A VEGETABLE: Sun; AS A HEALING PLANT: Saturn, Jupiter

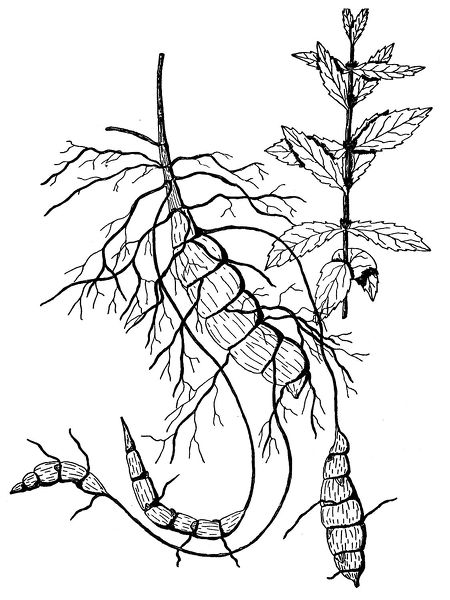

Knotroot is a parvenu in Western vegetable gardens. It was planted commercially for the first time in the Western Hemisphere in 1887 by Vilmorin-Andrieux et Cie, a French gardening company in the small town of Crosne. As a result, the root vegetable that originated in Japan (Japanese: chorogi; Chinese ts’ao shih tsan) became a popular delicacy in France under the name “crosne,” or “crosne du Japon.” To many it tastes like a mixture of oyster plant, potato, and artichoke; it reminds others of cauliflower. The pearl white tubers grow to about one or two inches long, underground runners that become thick at the root end and look kind of like the marshmallow-like Michelin Man or Bibendum. The tubers are good grated raw into winter salads, cooked as a vegetable with meat dishes, or mixed in with wok vegetables. The skin is very thin and does not need to be peeled. In China, Korea, and Japan, where they’ve been cultivated for hundreds of years, they are also pickled in vinegar. Instead of starch the tubers have stachyose, a kind of sugar (tetrasaccharide), which is composed of two molecules of galactose and one molecule each of fructose and glucose.

Above ground, this East Asian member of the mint family, which German-Dutch botanist and Japan researcher Phillip Franz von Siebold first described, looks like our mints, especially lemon balm. It is planted similar to potatoes—in rows that have been well composted. Knotroot/Chinese artichoke multiplies very well, especially in a sunny spot. In the late fall one can harvest as needed. They do not keep well once harvested so it is best to harvest fresh for each use.

Illustration 91. Knot root

The use of Chinese artichoke as a vegetable is not entirely foreign to us. Since pre-Christian times a close relative was gathered as a vegetable in Europe: marsh woundwort or marsh betony (Stachys palustris), which also has underground runners with thick tubers. John Lightfoot (1735-1788), a British scholar versed in plant lore, mentioned marsh woundwort in 1787 as a plant gathered for food. And in 1850 this kind of betony was experimentally cultivated for its edible root.1

The genera Stachys, to which knotroot belongs, contains many formerly important healing plants, including woundwort betony, lamb’s ear, and bishop’s wort. They are called “ziest” plants in German, ziest from the Slavic èist,meaning “pure.” Almost all these plants were considered cleansing and wound healing, as indicated in the name “woundwort.” English herbalist John Gerard (~1545-1612) called woundwort “clown’s woundwort” because of the many bruises and cuts treated with the plant that fools got from brawling in taverns. Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654), who put it under the rule of Saturn, made syrup with it to alleviate inner bleeding and coughing blood. Native Americans drank tea made from related betonies for stomach aches and cramps; externally they used it to wash and heal wounds, and for venereal diseases they applied a poultice made with the leaves and roots. For the Germanic tribes such as the Anglo-Saxons, and later for the peasants, the perennial yellow woundwort (Stachys recta) was an important heal-all plant—a standard in the apothecaries of earlier times. The herb was used externally as a bath and as a poultice and internally as tea for mucous congestion, stomach cramps, jaundice, kidney and bladder ailments, menstrual ailments, nervousness, epilepsy, and “to improve the fluid balance in the body.”

Betonies were also generally used to counter bad magic spells: when an ailing person bathed in a decoction of the plant, the bad magic ended up being tossed out with the bath water. It was also believed that plants from this family could purify the soul, and Anglo-Saxons of old are said to have used them against witchcraft. Presumably knotroot also possesses these qualities, and perhaps it was used similarly in East Asia. But getting to the bottom of that would be a task for ethnobotanists to tackle.

Recipe

Roasted Knotroot and Stinging Nettle ✵ 2 TO 4 SERVINGS

4 tablespoons cold-pressed olive oil ✵ 1 teaspoon finely ground coriander seeds ✵ herbal salt ✵ 1 pound (455 grams) knotroot, washed thoroughly or brushed ✵ 1 cup (225 grams) stinging nettle leaves, very finely chopped ✵ ½ teaspoon vanilla powder ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) cream (18% fat)

In a medium pan, heat the olive oil; when hot, add the coriander and herbal salt and sauté briefly. Add the knotroot and sauté gently until tender, about 10 minutes Add the nettle leaves and vanilla and continue to sauté for about 1 minute or until nettles are cooked. Add the cream. Serve hot.