A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Forgotten, Rare, and Less-Known Vegetables

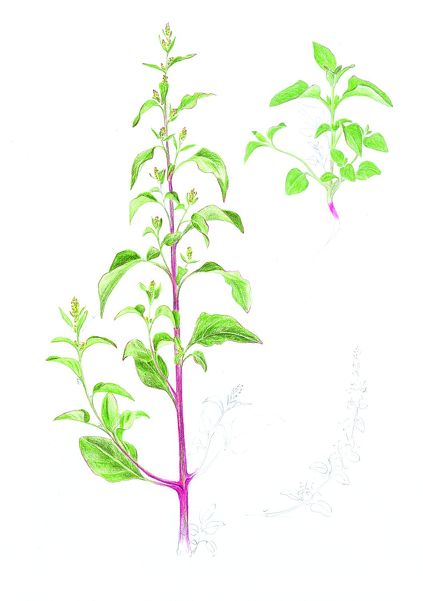

Green Amaranth (Amaranthus lividus, A. blitum, A. viridis)

Family: Amaranthaceae: amaranth family

Other Names: blite, pigweed, slender amaranth

Healing Properties: stops bleeding (hemostatic), regulates lung function; helps heal leukorrhea and venereal diseases

Juice: as a tonic for pregnant women, small children and the elderly

Symbolic Meaning: Huitzilopochtli, food for the gods (Native American)

Planetary Affiliation: Saturn, with Venus and Mars

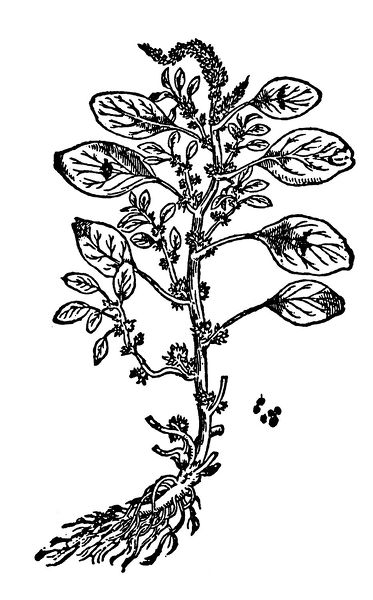

There are many kinds of amaranths. They have been cultivated for at least five thousand years as leaf vegetables—mainly in America—and as “grains.” The kind that is indigenous to Europe is called “blite” (from the Greek bliton) or “meyer” in German. Its stems are often prostrate, radiating from a base and forming a mat. Its dark green, sometimes reddish leaves and can be found in Europe as a garden weed or as a wild plant on pastures, roadsides, and around refuse dumps.

Green amaranth was taken into human culture relatively early in history. In the third century BC, Greek botanist Theophrastus wrote that “bliton” was cultivated as a vegetable and pot herb. In the first century AD herbal doctor Pedanius Dioscorides wrote: “The vegetable agrees very well with the body although it has no medicinal properties.” (So he thought; others would disagree.) And in the eighth century Charlemagne listed “Blidas” in his orders regarding the cultivation of his land holdings. Many other early botanists and herbalists also mention the vegetable. It was not until the worldwide reach of Popeye’s spinach came along that green amaranth was forgotten in Europe. Only the Greeks stayed faithful to the pot herb, who know it as “vlita”; they cook it and serve it with olive oil, lemon, and salt.

The Americas knew the plant as well. Central and South Americans cultivated amaranth for nearly eight thousand years; for the Aztecs it was a staple food. The young leaves are used like spinach and the ripened seeds—each plant has up to half a million shiny seeds like poppy seeds—are dried and threshed out. The seeds are roasted or steamed and/or ground and mixed with cornmeal. They are also mixed in with flat bread, baked into cakes, or cooked as porridge.

Illustration 90. Green amaranth (Joachim Camerarius, Neuw Kreütterbuch, 1586)

Also edible are the leaves and seeds of our garden-variety amaranth, known as foxtail amaranth, or love-lies-bleeding (A. caudatus). In their place of origin—Central and South America—they were regarded as sacred plants. For the Pueblo Indians they are the primeval nourishment, brought by their ancestors from the fourth world (under the earth) to the fifth world (here on this earth). The red leaves and blossoms of some kinds of foxtail amaranth are pressed and used as ceremonial body paint. Sacred cornmeal waffles (hé we) are also colored with these plants. The gods, the kachinas, who on their visit to earth manifest as masked dancers, carry these waffles with them as they dance and toss them to the spectators.

For the Aztecs amaranth grain was one of the most important “cereals.” Ten thousand baskets, each weighing some fifty pounds, were brought each year as tribute to the imperial city, Tenochtitlán. The high priests formed figures of Huitzilopochtli, the “humming bird of the south” and son of the earth goddess, with a red paste made of the ground seeds mixed with blood. These figures, called “zoale,” were carried ceremoniously to the pyramids. There they were broken into small pieces and distributed among the people to eat as communion, as the flesh and blood of the gods. The Spanish priests, still under the fresh impression of the Inquisition, saw this as a satanic mockery of the sacred Christian Holy Communion. For this reason, the amaranth plant that produced these seeds was forbidden.

The Spanish authorities were perplexed that the subjugated natives of Mexico and Peru repeatedly found the strength to rebel.1 At some point it became apparent that the reason must be because “… they eat a certain fruit that is no bigger than a pin head” (from a report to the Spanish viceroy, 1560). Amaranth, which contains high-quality nutrients, was thus considered responsible for the vitality of the Indians. (Because it contains large amounts of lysine, an essential amino acid, it is an ideal supplement to corn; it also contains a lot of leaf protein, vitamins, and minerals.) To break the resistance of the Indians for good, the devilish plant was to be exterminated. This is how it came to be that amaranth—unlike corn, potato, and tomato, and other Native American plants—did not find its way into our European food spectrum. At some time, though, probably thanks to the Portuguese, amaranth found its way to India. It became a mainstay grain (tampala) for quite a few hill tribes in the Mysore area and in the Himalayas. Among other names the Indians call it “ramdana” (God’s gift). The use of this valuable plant as both a green vegetable and a grain spread to Africa as well.

In India and China closely related kinds of amaranth are cultivated—as in chaulai, Chinese spinach. Contrary to Dioscorides’s assertion, Ayurveda considers amaranth a healing plant; for instance, fresh juice with honey is given to drink for chronic lung ailments such as asthma, emphysema, and tuberculosis. It is thought that pregnant women should enjoy the juice with honey and a pinch of cardamom during their entire pregnancy in order to ease the birth and increase their milk. The juice is given to infants and to the elderly, whom it helps keep fit. It is also said to help for inner bleeding, gum and nose bleeding, excessive menstrual bleeding, and hemorrhoids. For leukorrhea, gonorrhea, and other venereal diseases it is recommended to boil the grated root in water and drink the concoction on an empty stomach in the morning (Bakhru 1995, 88; Dastur 1962, 18). Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) also confirmed that the plant helps to stop bleeding and with venereal diseases; he used the powdered blossoms, however, claiming it takes Saturn to rein in a naughty Venus.

In modern times the seeds of New World amaranth varieties have attracted attention as a possible means of feeding the ever-increasing world population. Indeed, the pseudo-cereal has been called a “crop of the future.” We would do well to acknowledge this tasty, nourishing plant and try the leaves as a green vegetable or the delicious seeds in various ways.

Recipe

Warm Vegetable Strudel with Green Amaranth ✵ 4 SERVINGS

½ cup (115 grams) potatoes, peeled or unpeeled, grated ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) carrots, scrubbed and grated ✵ 1 tablespoon olive oil ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) green amaranth, finely chopped ✵ 1 pinch ground nutmeg ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ 2 egg yolks, whisked ✵ 10 ounces (285 grams) pastry dough

FILLING: In a medium pan sauté the potatoes and carrots in the olive oil for 5 minutes. Add the amaranth and continue to sauté for a few more minutes or until tender. Transfer the vegetables to a sieve and let drip into the sink. Season with nutmeg, salt, and pepper to taste. Return the vegetables to the pan to mix in the egg yolks.

STRUDEL: Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Grease a baking sheet. Roll out the dough until it is about ¼ inch thick. Transfer to the baking sheet. Spread the vegetables evenly on the dough, leaving a half-inch margin at the edge. Roll into a strudel shape. Brush with water. Bake at 350 °F (175 °C) for 35 minutes. Serve hot.

TIP: This dish pairs nicely with a green salad.