A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, Lycopersicum esculentum)

Family: Solanaceae: nightshade family

Other Names and Varieties: apple of paradise, gold apple, love apple; beef tomato, cherry tomato, pear tomato, yellow tomato

Healing Properties:

TAKEN EXTERNALLY: fresh juice helps disinfect wounds

TAKEN INTERNALLY: increases pancreas secretion; regulates bowel movement; inhibits tumors (anticarcinogenic); ideal in diets for gout, kidney and heart ailments, rheumatism

Symbolic Meaning: temptation, Eve’s apple, love madness, egoism, sex and fertility

Planetary Affiliation: Mars, Venus

Next to potatoes, tomatoes are definitely the favorite of cultivated garden fare. The tasty, beautifully colorful, juicy vegetable—though technically a fruit—has won the hearts and tables of people all over the world. But that was not always the case. When in the early sixteenth century the Spanish discoverers first saw tomatoes in Central America, they were more than skeptical about eating them, having immediately recognized the tomato as a nightshade plant. During this era of witch persecutions and the Inquisition in Europe, nightshade plants—such as henbane, belladonna, mandrake, and angel’s trumpet—weren’t just known to be extremely poisonous: they were also considered evil, belonging to the devil. For the Spanish conquerors, nightshades were associated with witches and their wicked brews and salves that led to licentiousness, whoring, and other damnable activity.

There was also another practice that did not exactly speak for the innocent plant. Spanish chroniclers reported in disgust that the Aztecs sacrificed their war captives, cutting out their still-beating hearts in offering to the sun god. The remaining meat of at least some of the victims was later prepared in a stew seasoned with tomatoes and chili peppers and served to noblemen. (While scholars do not agree on the extent to which cannibalism was practiced by the Aztec nation, they do agree that it took place on occasion, especially for ritual purposes.) According to the conquerors, it would be hard to find anything more devilish on God’s earth. (It did not occur to them that they themselves came from a culture that cruelly tortured other—mainly completely innocent—human beings in God’s name, and where pyres burning “witches” were constantly aflame.)

Illustration 83. Tomato blossoms (illustration by Molly Conner-Ogorzaly, from B. B. Simpson and M. Conner-Ogorzaly, Economic Botany, 1986)

Of course, the Aztecs also used tomatoes as medicine; unfortunately, most of their recipes for healing are hard to follow. For instance, to treat “facial star disease” a mask was made of lizard manure, soot, and tomato juice. The drink for convalescing and general strengthening—fresh-pressed tomato juice, ground pumpkin seeds, yellow paprika, and cooked agave juice—certainly sounds much more pleasant. For asthma and other lung ailments they put cooked tomatoes, made as hot as possible, on the chest, rubbing them in with copal resin as soon as they were cool enough.

For the Mayans, tomatoes were daily fare. They believed that tomato juice increases red blood (in which life force resides) in humans, and thus strengthens the body. They also treated skin infections and hemorrhoids with fresh tomato juice (Rätsch 1996, 272).

Tomato comes from the Aztec word “tomatl,” which means something along the lines of “a firmly swollen thing.” European botanists came up with other names for the suspicious fruit. First was lycopersicum, “wolf’s peach.” The “peach” of this name they got from a not very detailed description of an old Egyptian poisonous plant—presumably mandrake—that also has golden yellow berries and that the renowned Roman doctor Galen had mentioned in his writings. The “wolf” derived from the fact that heathen Europeans called all plants that are poisonous, caustic, or even “malicious” “wolf plants.” The distinguished German physician and member of the Royal Society, Dr. Michael B. Valentini (1657-1721), wrote: the tomato “is called ‘wolf’s peach’ because, though it is pleasing to the eyes, if people eat it, it can kill them, just as wolves can.” The fruit was also called “apple of insanity” (mala insana) and “golden apple of a stinking smell.”

Illustration 84. The Spanish associated barbarous human sacrifice with tomatoes

Other botanists of the sixteenth century thought of friendlier names for the new plant, such as “love apple” (poma amoris) or “paradise apple.” But even in these names convey a basic mistrust, a fear of eroticism and sensuality. The fruit, juicy and red like voluptuous lips, and full of slimy seeds, reminded scholars of fatal female temptation. In Germany, a hot chick is still called a “hot tomato”—who might though turn out to be a “sour” or “fickle tomato”—and a temperamental woman is called a “tomato with pepper” (Bornemann 1991).

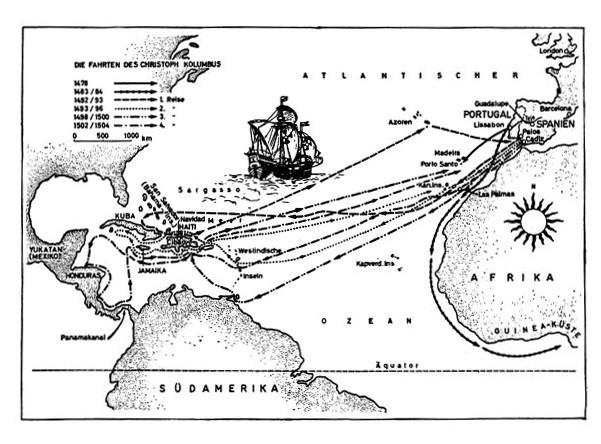

When tomatoes first became known the scholars of the time puzzled as to whether it could be the forbidden fruit that once grew on the Tree of Forbidden Knowledge in the Garden of Eden. Their suspicion derived from the report of Christopher Columbus of his third voyage, which had taken him to the mouth of the Orinoco River on the coast of South America. Columbus wrote that the region was beautiful beyond measure, the vegetation was lush, the animals were peaceful, and the natives were handsome and pictures of perfect health. In all seriousness, he believed he had landed on the border of Paradise, the Garden of Eden described in sacred texts. Could it be that the many wild tomatoes that grew there were descendants of the forbidden fruit? The name “paradise apple” noted earlier became relatively widespread. For example, such was the name used in the countries belonging to the Habsburg Empire—Bohemia, Silesia, Yugoslavia, and Tyrol; in Scandinavia they are still known as “paradise apples”: paradisaeble, paradisaepple. And today in Vienna only strangers buy “tomatoes” on the famous Naschmarkt; the Viennese buy Paradeiser. In the Odenwald, near the Rhine, locals still call the fruit “Adam’s apple” in memory of the first victim of female seduction.

Illustration 85. The Voyages of Christopher Columbus

Even though people were suspicious of this exotic “love apple” or “gold apple,” it did find a place in European gardens—as a decorative plant. As an expression of his otherwise inexpressible hopes and wishes, many a suitor pooh-poohed the usual gift of flowers, giving the lady he hoped to win a basket of ripe, lush red tomatoes instead. For a long time tomato juice was considered to be a secret love potion, one that in the eyes of the Puritans “leads to licentiousness”—as wrote modern-day ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch, an expert on aphrodisiacs.

Gradually, however, the tomato’s medicinal properties were discovered. According to its signature, the red fruit was believed to heal wounds. The fresh juice was trickled into wounds in order to prevent the build-up of pus and the development of erysipelas. Those who were versed in medical lore experimented with tinctures made of fresh stems. They got the idea from the similar fruits of the bittersweet nightshade, which was used for pustules and skin diseases of a scrofulous nature, such as occurred from syphilis and the misuse of mercury salves. According to the way of thinking of the times, it was only logical that this “love apple” could alleviate the symptoms of venereal disease, the disease with which the goddess of sensual love, Venus, had smitten humanity. After all, it was Columbus’s sailors who first contracted the dreadful sexually transmitted disease, bringing it back with them from the New World. The medical doctrine of the time stated that the place where a sickness originated was also where the cure could be found.

But it would take until the sixteenth century before Europeans ever considered eating tomatoes. The Italians were the first to dare to eat the dreaded fruit. Perhaps it was a rejected lover who wanted to take his own life with the poma amoris, the apple of love; perhaps it fell onto his toasted bread, or into his pasta of olive oil, garlic, and parsley. In any case, botanist Joachim Camerarius the Younger (1534-1598) wrote: “In Italy many have the habit of eating these fruits cooked with salt, vinegar, and oil, but it is a very unhealthful food.” In time, Italy became the second home for tomatoes, which plunged into intimate wedlock with pasta. By the eighteenth century, entire fields of tomatoes were under cultivation in northern Italy. Farmers from the region of Parma were the first to conserve them by cooking the juice or drying the fruits in the sun.

It took the northern and western Europeans and North Americans very long to overcome the taboo of eating tomatoes. Though herbalist William Salmon (1644-1713) reported seeing tomatoes growing in the early American colonies—in what is now South Carolina, in 1710—it was presumably only as an ornamental plant. An American colonel named Robert Gibbon Johnson was declared crazy in 1820 when he announced that on September 26 he would publically eat a whole basket of tomatoes while sitting on his open porch. On the appointed day more than two thousand curious onlookers appeared to witness the spectacle; to the astonishment of all—excepting himself, we presume—he survived.

Illustration 86. For a long time it was believed that the tomato was the “apple of paradise” that had caused humanity to plunge to its perdition (Baum der Erkenntnis, 1531)

In as late as 1866 in Northern Germany the “love apple” was still considered an ornamental plant, whereas in Southern Germany it was cultivated and eaten as a side dish or as an ingredient in soups. But still scientists and physicians has their doubts: they claimed that, as an acid-producing vegetable, the tomato acidifies the blood and body tissue and makes it susceptible to rheumatism, gout, and arthritis—and, worse, it supports cancer. (Today we know that exactly the opposite is the case.)

It was not until after 1920 that the tomato became really popular. Agribusiness cultivated huge fields of standardized hybrid tomatoes1 in the new arable areas in the desert of Southern California. As a result the U.S. market was flooded with tomato juice, tomato paste, canned tomatoes, tomato soup, and ketchup.2 For Hollywood stars, tomato juice became as much a part of the daily ritual as orange juice and spinach; and during Prohibition a popular cocktail, the “Bloody Mary,” nicely disguised the vodka lurking within. Today the average American eats some fifty pounds (twenty-five kilos) of tomatoes a year.

Not long after, doctors found their way to attesting considerable health advantages to the newly fashionable and profitable vegetable. They [correctly] reported that tomatoes are good for dyspepsia, liver troubles, gout, rheumatism, and heart and kidney ailments. Fresh tomatoes increase pancreas secretion and stimulate bowl movement. In addition they are full of high-quality vitamins, including vitamin C, carotene (a pre-stage of vitamin A), thiamine, and vitamin E, the “fertility vitamin.” Folk healers also befriended the vegetable. Modern-day herbal healer Maurice Mességué recommends it for acidosis (stomach acidity, such as in heartburn), constipation, for thinning the blood, and for gout-related ailments. He also recommends hanging the stems and leaves in closets to keep out moths and insects.

Anthroposophists, however, still have doubts about the tomato. They note that this nightshade plant just does not have the proper “power to grow upright,” that the tomato is “weighed down with matter.” The anthroposophically oriented botanist Alfred Usteri (1869-1948) was suspicious of what he called “a rapacious plant that thrives on its own composted waste and debris.” He claims the tomato reflects the materialism that took root in the beginning of the fifteenth century and that is the mirror image of the human egoism that led to racism, nationalism, and consumerism. The tomato, thus, can cause diseases in the human being, which represent the physical expression of these mental configurations. In other anthroposophical writings there are also warnings about the “surplus expansive force” in the tomato, and about the “misguided formative forces that can help promote cancer, rheumatism, and gout” (Pelikan 1975, 186).

It is interesting to note that recent research indicates exactly the opposite: the tomato is anticarcinogenic. In fact, there are statistically fewer cases of cancer in areas where a lot of tomatoes are eaten. One study has shown that—thanks to the high concentration of the carotene lycopene—it is especially beneficial for lung cancer. The fruit’s lycopene content makes it one of the top-rated antioxidant foods as well.

And what about the crazy imaginations that deemed the tomato a witch’s plant that can cause insanity and hallucinations? Those myths have long since been cleared up as well. The glycoalkaloid solanine found in tomato leaves and stems is indeed poisonous; it can cause dizziness, nausea, gall and kidney irritation, cardiac flutter, profuse sweating, cramps, and unconsciousness—but it is absolutely not a psychedelic. Or maybe it is, just on another level? Or maybe it has a tendency in that direction? I would like to share an unusual, enlightening experience the tomato once gave me. I had been busy all day in a large biodynamic garden near Geneva, Switzerland, tying tomato plants to posts and pinching off side shoots. The aromatic evaporation of the plants in the closed-off plastic tunnel was almost overwhelming. As is usual when doing that kind of work, I let my thoughts wander. I was thinking about Buckminster Fuller’s 1967 hypothesis of our “spaceship Earth” and about the fragile, thin film of chlorophyll upon which all life on earth depends. In my mind’s eye I saw the unnecessary destruction of the forests and the spreading of the deserts. The thought that “we are living on a dying planet” overwhelmed and saddened me. But suddenly I felt “beamed” into another dimension. An angel or god—it must have been the tomato deva—said to me: “You are wrong. The green cloak of the earth is only an external expression of the fullness of life that flows through the entire universe. Life and consciousness belong to the essence of being, not just matter and energy, and they cannot be irrevocably destroyed. Do not worry, just do your work and do not be afraid!” That message came from such depth that it has become a lifeline for me. To this day I am thankful to the tomato for giving me this insight. I know that it is not an “uncanny spirit” that lives in the plant, but a strong and friendly one.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Tomato seeds should be started indoors about eight weeks before the last frost. Tomatoes should be planted in an open place, for they need full sun and good air circulation for maximum growth and production. The soil can be well composted in advance of planting; an extra handful of well-aged compost may be thrown in the planting hole before you transplant. You should plan to stake your tomatoes. Drive in a stake at planting time and tie the young plant to the stake (tightly around the stake and loosely around the tomato stem.) After that allow just two main shoots to grow, pinching off any side shoots, until the plants have reached about two feet in height. After that you can allow side shoots to develop. Keep the shoots tied to the stake as they grow. (LB)

SOIL: Tomatoes grow best in a sandy loam that offers good drainage and aeration. Never plant tomatoes where puddles form, for this indicates poor drainage and a great possibility of bacterial wilt, stunting, and fruit rot. Good air circulation is equally important, since this will help prevent blights and fungal diseases.

Recipes

Tomato Salad with Plums and Plum Vinegar Dressing ✵ 2 TO 4 SERVINGS

SALAD: 4 ripe tomatoes, cut into ¼ inch slices, 4 firm, tart plums, cut into slices ✵ sea salt ✵ pepper ✵ 3 ounces (80 grams) alpine cheese, coarsely grated ✵ DRESSING: 2 tablespoons plum vinegar ✵ 5 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 3 ounces (80 grams) onions, finely chopped ✵ some chives, finely chopped

Layer the tomatoes and plums in a serving bowl. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Sprinkle the cheese over top. In a small bowl, mix the vinegar, olive oil, onions, and chives. Drizzle over the salad.

Tomato-Potato Soup with Marjoram and Nuts ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1½ pounds (680 grams) potatoes, peeled or unpeeled, cubed ✵ ¾ pound (~350 grams) onions, chopped ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 4 tomatoes, cubed ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ sea salt ✵ pepper ✵ fresh marjoram ✵ 4 garlic cloves, chopped ✵ 2 ounces (50 grams) raw pumpkin seeds ✵ 3 ounces (80 grams) cottage cheese

In a large pot, sauté the potatoes and onions in the olive oil, covered, for about 8 minutes, stirring regularly. Stir in the tomatoes and cook for another 2 minutes. Pour in the vegetable broth. Bring to a boil and boil for 1 minute. Move the pot off the burner and season with ground nutmeg, honey, salt, and pepper. In a small serving bowl, mix the marjoram, garlic, pumpkin seeds, and cottage cheese; season with salt to taste. Serve with the soup.