A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Red Beet and Swiss Chard (Beta vulgaris)

Family: Amaranthaceae: amaranth family; formerly Chenopodiaceae: goosefoot family

Other Names: beetroot, beta, chard, borscht, mangelwuzel, mangold

Healing Properties: regulates acidity, builds blood, activates liver metabolism, inhibits tumors

Symbolic Meaning: keeps us “grounded”; spirit of rationality

Planetary Affiliation: Mars, Saturn (Culpeper); SUGAR BEET: Jupiter

The beet is the most intense of vegetables. The radish, admittedly, is more feverish, but the fire of the radish is a cold fire, the fire of discontent not of passion. Tomatoes are lusty enough, yet there runs through tomatoes an undercurrent of frivolity. Beets are deadly serious. Slavic peoples get their physical characteristics from potatoes, their smoldering inquietude from radishes, their seriousness from beets.

With these lines the red beet, otherwise denounced as a boring vegetable, stepped on to the stage of world literature from the first page of Tom Robbin’s 1984 novel Jitterbug Perfume. And though an old Ukrainian proverb warns that “a story that begins with a red beet ends with the devil,” Robbins was willing to take that risk.

Unlike all other vegetables, the red beet exits our body with the same color it had when it entered. Borscht, the favorite soup of the eastern Slavic peoples, is red due to red beets, which are a significant part of eastern European folk culture. (Though this root vegetable is not quite as well known in western Europe, health enthusiasts do know about vitamin-and-mineral-rich red beet juice and tasty beet salad made with cooked red beets and onions.)

Many years ago, an elderly woman told me that red beet “builds up blood.” At the time I could barely hide my skeptical smile; just because the red beet turns the stool red does not mean it’s good for the blood. To me, such was as much an old superstition and outdated “signature teaching” as Enlightenment scientists considered of similar claims made by ancient Greeks and Romans, including Dioscorides, Galen, or Pliny the Elder. But, despite criticism, traditional folk belief held on to this claim—which was based on experience handed down from generation to generation.

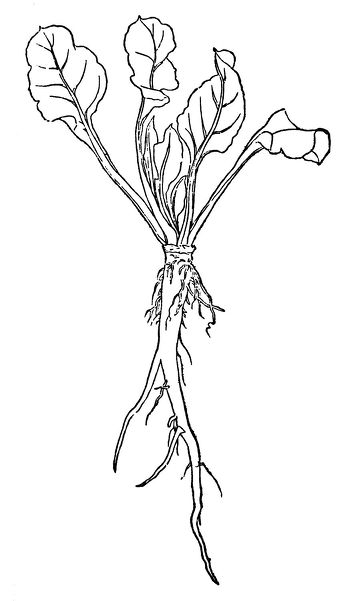

Illustration 71. Swiss chard (Otto Brunfels, Herbarum Vivae Eicones, 1532)

It turns out that recent clinical research supports the traditional folk belief. Red beet juice is given for leukemia, anemia, and malaria as it is thought it helps regenerate and increase red blood corpuscles. The juice also traps radicals and contributes to lowering elevated blood fat levels, the latter of which has a positive effect on the health of the heart and circulatory system. The traditional folk medicine belief that expectant mothers should eat plenty of red beets is another example: it so happens that the juicy globes contain exceptional amounts of folic acid, a vitamin substance that helps the embryonic vertebrae develop properly so that there is no risk of spina bifida.

Swiss herbal healer Alfred Vogel (1902-1996), popularly known as “the little doctor,” considered red beet juice supportive in case of viral flu, Hodgkin’s disease, blood pressure ailments, irritated appendices, and—because of its iodine content—goiter. It activates gall bladder and liver metabolism. Research done by Dr. Alexander Ferenczi in 1961 made headlines when he claimed to have discovered anti-tumor properties in betaine, which is responsible for the color of red beets. In his study, patients who’d drunk one liter of fresh beet juice daily for three months showed a stronger blood count than did the control group. It should be noted that, though such was a medical study, establishment medicine strongly doubts this positive effect. But naturopaths point out that not all red beet juice is alike; only beets that are grown organically (without artificial nitrate fertilizer) and get full sunlight can produce juice that has therapeutic value. But whether the juice actually helps heal X-ray and other radioactive damage—as medical doctor S. Schmidt from Germany claims—is another question.

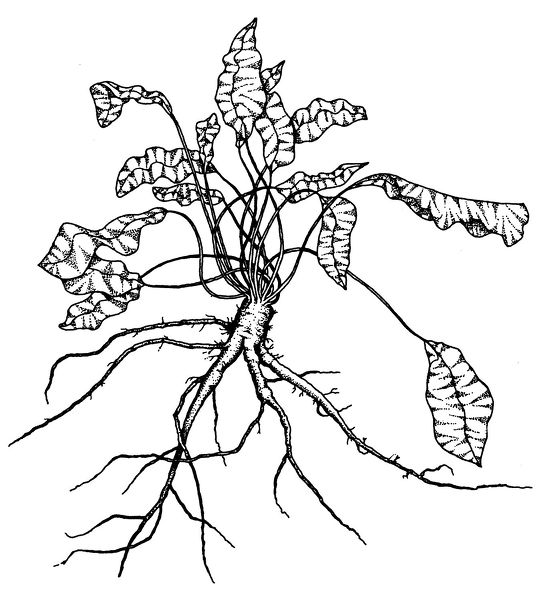

Illustration 72. Red beet in full blossom (Leonhart Fuchs, De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes, 1543)

Chinese traditional healing lore uses the red beet globe to strengthen the heart, regulate conditions of agitation, rev up a sluggish liver, ease the hormonal concerns of menopause, and improve the blood. Ayurvedic medicine also praises the beetroot as a blood builder since it supports a healthy base-acidic balance, which helps to prevent the body tissue from becoming overly acidic. As in the European tradition, Ayurveda also uses the juice for liver disease, constipation, and intestinal ailments. For bad skin, pimples, pustules, or even scabs on the scalp, Indian medicine prescribes the following: the water in which red beets have been cooked is mixed with vinegar in a 3:1 juice:vinegar ratio to be used externally or massaged into the scalp. It is interesting to note that in 1649 Nicholas Culpeper noted a similar recipe—a decoction of red beet water with vinegar—for cankerous abscesses, boils, tumors, blisters, frostbite, scabies, dandruff, and even hair loss. Culpeper, who was also an astrologist, puts the plant under the rule of Saturn because of its “mineral nature.” Others stress the influence of Mars because of its blood building properties and its color.

Illustration 73. Wild chard: precursor of the red beet, sugar beet, Swiss chard, and Good King Henry

Like spinach, orache, and Good King Henry (which we discuss among other forgotten, rare, and less-known vegetables), the red beet is a Chenopodium or goosefoot plant. Chenopodiums thrive best on salty, alkaline, strongly mineralized soils of the salt steppes, along seashores, as well as on rubble and garbage dumps near human settlements. The original wild plant (Beta vulgaris var. maritime) still grows as a tough-leafed beach plant on the coast of the Mediterranean, the Caspian Sea, the Dead Sea, and the North Sea. Prehistorians assume that foragers as far back as the Stone Age gathered the plant for soups. Surely they cooked it with meat and other ingredients as by itself it has a rather caustic, unpleasant, bitter taste—due to its saponins and oxalic acid, substances that make the teeth feel “dull.”

The oldest archeological findings of this plant are from a New Stone Age settlement (4000 BC) in Holland. Ethnobotanists assume, however, that it was first cultivated intentionally in the Mediterranean area, specifically in Sicily. From the wild form, primitive farmers selected and cultivated two kinds: a beetroot (usually red, but sometimes yellow) and a leaf vegetable—the precursor of Swiss chard. We also know that “silqua,” as the bulb was called in the antique Near East, was cultivated in the gardens of the Babylonians and Phoenicians in the second century BC, and that red and white beets were sold in Athenian markets in the fourth century BC.

Since seed bundles of red beets or Swiss chard were found in Roman military camps and civilian settlements in the Rhine-Main river areas, it’s clear the Romans brought the cultivated “beta” (from this Latin term comes our word “beet”) to their cold, foggy provinces in northern Europe. But, apparently, the Germanics and Celts were not particularly interested in the new vegetable, content as they were with their turnip (Brassica rapa subspecies rapa) or the yellow turnip or rutabaga (B. napus). And though Charlemagne (742-814) ordered the cultivation of the beta throughout his Western European land holdings, and monks cultivated it in cloister gardens, for hundreds of years red beets scarcely had a place at the northern table.

Not until the sixteenth and seventeenth century is the vegetable—the red root globe as well as the leaf chard—mentioned again. At that time Europeans were turning away from the otherworldly mysticism of the High Middle Ages and beginning to focus more attention on the material world and its laws. Interest in alchemy gave way to interest in the “hard science” of chemistry; the belief that good or bad health was the result of witch’s spells or demonic influence gave way to belief in logical reasoning and mechanical natural laws—as presented by enlightened medical doctors. Similar to the potato, which came somewhat later to northern Europeans, the beta played a significant role in the nutritional paradigm change that took place at that time. (From there European settlers brought the beet to America and though it is not clear when the plant arrived, it was well known there by the eighteenth century.)

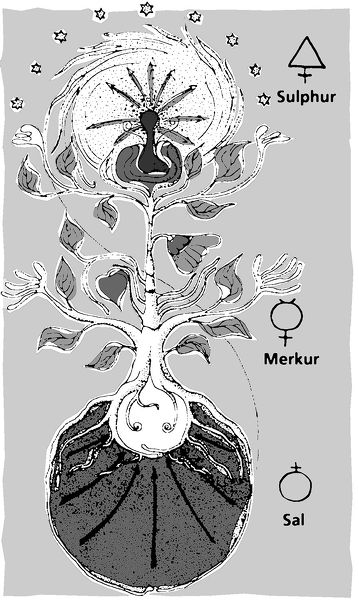

To better understand how the beet fit into the nutritional paradigm it behooves us to take a closer look at one of the basic ideas of alchemy. The alchemists, the forerunners of our empirical scientists, distinguished three states of matter, three formative, active building principles in nature: sal (salt), mercurius (mercury), and sulfur. They described sal as absorptive, receptive, concentrating, consolidating, and hardening. The power of “salt” is focused in the human anatomy in the head, with its hard skull and its ability to concentrate thought and gather impressions from the senses. With plants the sal-force is the strongest in the root, the densest part of its anatomy, which takes up water and minerals from the surrounding soil.

The second state of matter, sulfur, is the diametric opposite of sal. As a principle “sulfur” is a centrifugal force, bringing about dissipation, dissolution, and evaporation. In the human being this pole is found in the lower body: in the reproductive and digestive organs and in the function of excretion. In plants the sulfur processes take place in the blossom, where the plant dissipates itself in scent, nectar, and abundant seed production—thus communicating with its environment.

The principle of mercurius is characterized by rhythm and fluctuation between the two outer poles. In human anatomy this is expressed in the inhale/exhale working of the lungs as well as in the heartbeat, with its rhythm of systole and diastole animation. In plants the mercurial principle is located in the region between the root and the flower, namely in the stalk and leaf regions where rhythmic growth takes place and gases—oxygen and carbon dioxide—are exchanged between the plant organism and the atmosphere.

If we apply this threefold system to the red beet, we recognize that the sal pole is predominant in the plant. The root bulb greedily absorbs and concentrates various minerals—calcium, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, iron, copper, sulfur, iodine, boron, lithium, strontium, chlorine, and also traces of rare minerals such as rubidium and cesium. Like other members of the goosefoot family, this plant is immune to salt. It even takes to a bit of cooking salt sprinkled in the rows before sowing! By contrast, the sulfur pole of the red beet is very weakly developed, almost atrophied. Its tiny, unspectacular blossoms, without color and without scent, are barely noticeable. It is as if the colors normally found in the flowering pole have slid down two stories, right down into the soil. The sweetness, the nectar, which is usually concentrated in the blossom, is also drawn down by sal power into the root. Indeed, the bulb has so much sugar that in ancient Greece beet juice was boiled down to syrup and used as a healing elixir instead of honey. Crystallized beet sugar, to which we are increasingly addicted to in this materialistic age, is also the result of a sal process.

It is interesting to note that, as Western Civilization became more head-oriented and materialistic, beta vulgaris became a more interesting plant for the Europeans. During the time of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century—when rational thinking became dominant over gut intuition, and when the traditional medieval European three-field system was replaced by modern agricultural methods—this plant started to play a new and important role. At this time a new kind of beet was developed that was lighter in color and had more bulk, known as the fodder beet, mangelwurzel, or field beet. Fields that had previously been fallowed for one year were now planted on a large scale with these field beets. They were stored over the winter in big insulated heaps or shredded in silos similar to sauerkraut and served as fodder to the cows, swine, and other animals—thus the name “fodder beet.” This beet made it possible to bring more animals through the winter; as a result the meat supply for the population, especially for the well-to-do citizens, noticeably improved.

Illustration 74. Salt, mercury, and sulfur in the archetypal plant (illustration by Lambert Spix, from Wolf D. Storl, Der Kosmos im Garten, 2001)

Beta vulgaris contributed another achievement to the way of life at that time. The chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (1709-1782) demonstrated that this new beet contained considerable amounts of sucrose that was identical to precious cane sugar. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, pharmacist Franz Karl Achard (1753-1821) cultivated what became known as “the white beet of Silesia”: a bulb with a sugar content of 8.8 percent (today it contains around 20 percent). At that time, with Napoleon having conquered most of mainland Europe and a British navy embargo on all the ports, the continent was cut off from sugar imports from the Caribbean. But, thanks to the sugar beet, a mighty new industry grew in the shadow of the embargo. Granulated sugar, hitherto a scarce commodity available only to rich aristocrats or for medical use in apothecaries, suddenly became a cheap mass product—with wide-ranging results. The working masses thereafter could afford to generously spread their bread with energy-rich sugar beet molasses at breakfast and sweeten their substitute chicory coffee. Candy stores, alcohol stores, and soft drink companies flourished, as did dentists. To wit: Europeans became severely addicted to sugar. (Few people realize that sugar is an addicting drug!)

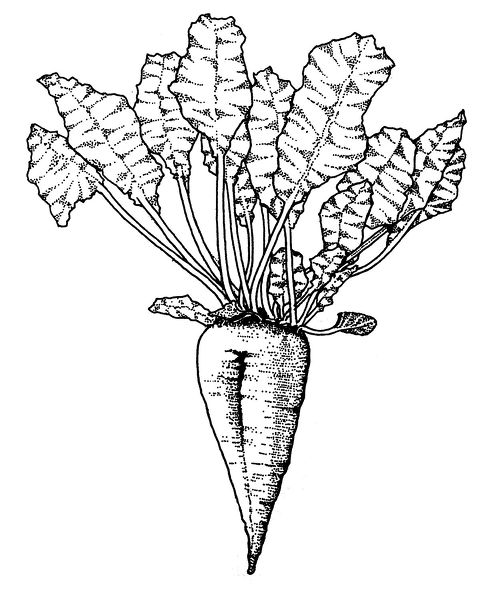

Illustration 75. Sugar beet

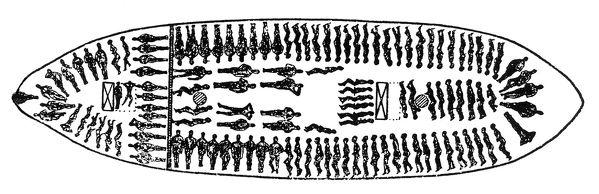

Illustration 76. Cultivation of sugar beets ended slavery in Central America; shown here, the loading plan of a slave ship

But the thus-lessened health of the sweetened Europeans had a significant benefit for humanity: the slavery-based sugar plantations in the Caribbean soon became unprofitable, ultimately leading to slavery being prohibited and abolished. In benefitting human beings who had been considered nothing more than working machines, the beet could be thought of as a plant deva, one that helped to establish human rights and “democratize” human culture.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: There are few plants that are easier to grow than red beets and Swiss chard. Sow the seeds directly in the bed as soon as the earth is ready in the spring; later, thin the plants to about eight inches apart. Swiss chard can be picked as soon as the leaves are nearly of a desirable size, as they will continue to grow after being cut. The fresh greens from thinning out red beets are delicious when prepared like spinach. (LB)

SOIL: Both red beets and Swiss chard grow well in any good garden soil as long as they have a sunny, open spot. Note that the vigorous roots can grow as far down as six feet, breaking up the subsoil and improving drainage wherever they roam.

Recipe

Red Beet Salad with Olive Sauce ✵ 2 SERVINGS

10 ounces (285 grams) raw red beets, cut into fine strips ✵ 2 green onions ✵ 1 cup alfalfa sprouts ✵ 3 ounces (100 grams) dried, pitted black olives ✵ 2 ounces (80 grams) hazelnuts, ground ✵ 4 tablespoons cold vegetable broth ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 2 tablespoons wheat germ oil ✵ herbal salt ✵ black pepper ✵ ½ cup lovage, finely chopped (for garnish)

Mix the olives, hazelnuts, broth, olive oil, and wheat germ oil in a blender on high until smooth. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

In a serving bowl, mix the onion and alfalfa sprouts. Arrange the beet strips on the spouts. Pour the olive sauce over the beets and sprouts. Garnish with the lovage and serve.