A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Radish (Raphanus sativus)

Family: Cruciferae or Brassicaceae: mustard family

Other Names or Varieties: black Spanish round, crimson giant, daikon, perfecto

Healing Properties: inhibits fungi and bacteria; activates gallbladder and liver; helps prevent gallstones, kidney stones, and bladder stones; improves intestinal flora; prevents scurvy (antiscorbutic); promotes urination (diuretic)

Juice: clears mucus (expectorant)

Symbolic Meaning: quarrel and strife, hardy vitality, affluence (Japan), spring and the perpetual renewal of life (Near East), an attribute of the wind and weather gods, St. Peter and Donar

Planetary Affiliation: Mars

Even though the radish is said to have originated in Northern China and has been cultivated there for thousands of years, most Europeans also consider it a native plant (Schwanitz 1966, 127).1 Black, white, purple, and red radishes rank among the favorite crops in Europe and the U.S. Radish roots were part of the daily food supply of the slaves who built the Egyptian pyramids, and the ancient Greeks used various radishes medicinally. Roman admiral Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) who wrote a thirty-seven-volume treatise on natural history (Historia naturalis) after his retirement from the military, reported that the Egyptians were mainly interested in the oil from the seeds. He also noted that radishes thrive in cold climates so well that in “Germania” a single one grew to the size of a newborn baby.

“Radih” (from the Latin radix = root) is the Old High German word for radish. In Bavaria they still call radishes “radi,” which they eat with their “soul food,” Bavarian veal sausage with sweet mustard, and their locally brewed beer. (Only the Japanese and Chinese eat more radishes than these southern Germans do.) In earlier times, “liquid bread” (beer) eaten with grated, salted radishes kept the country population healthy over the long winter months, as radishes contain enough vitamin C to protect against scurvy. In addition the root has vitamins A, B1, and B2, phosphor, and a lot of potassium. The glucosinolates in radishes also have an antibacterial and antifungal effect, which helps prevent colds. And those not minding their P’s and Q’s (pints and quarts) in the tavern could protect their livers by eating plenty of fresh grated radishes, which trigger hepatic metabolism and increase gall secretion. Bavarians prefer the quite strong black radish, usually grated and generously salted; sometimes it’s doused with fresh cream and eaten with buttered bread.

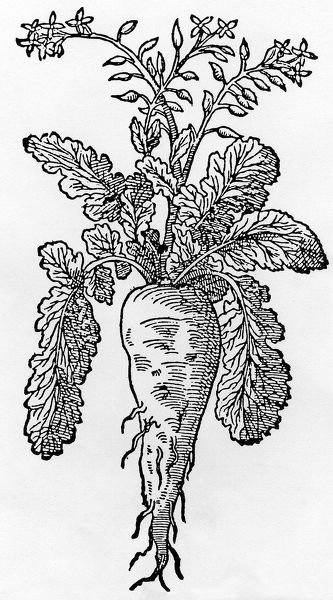

Illustration 67. Radish (Joachim Camerarius, Neuw Kreütterbuch, 1586)

The radish is—like most cruciferae, such as cabbage and horseradish—packed with vitality. Thanks to its sulfuric oils it can take cold outside temperatures, and it keeps well throughout winter in a cool, moist cellar or in a sandbank. The Bavarians say the radish compares to a strapping example of the male species: it is a kind of vegetable Arnold Schwarzenegger. Popular belief in Southern Germany and France claims men who eat a lot of radish will have a stronger erection due to the gases that accumulate in the lower body regions. Otto Brunfels (1488-1534), botanist and official city physician of Basel, Switzerland, noted, “Radish is also said to encourage unchastity.” The radish—as doctors of earlier centuries knew—has the signature of the masculine planet Mars. This is made obvious by its pungency and red color and by its effect on the Mars organ, the gall bladder. This gland, which produces bitter bile, was also seen in earlier times as the organ in which anger had its seat. (What in English is referred to as “breathing fire and brimstone” is called in German “spitting gall and poison.”)

Because Mars rules over the radish, it follows that it was a symbol for quarrel and strife in the Middle Ages. It was believed that especially quarrelsome spirits—such as the legendary and unruly mountain spirit Rübezahl (in Polish, Liczyrzepa; Krakonoš) at home in the mountain range between Bohemia and Silesia—were especially enthusiastic about this fiery tasting root vegetable. In the old “language of flowers,” with which court damsels and knights communicated without having to speak, wearing radish leaves or flowers meant: “Through you I have had to suffer a lot of pain and sadness.” Wherever the radish plant appears in old paintings it has a similar meaning. For example, in Albrecht Dürer’s 1496 painting The Prodigal Son, a young man kneeling in a pigsty has turned his back on a radish, meaning he is regretful and wishes to leave any disputes behind him.

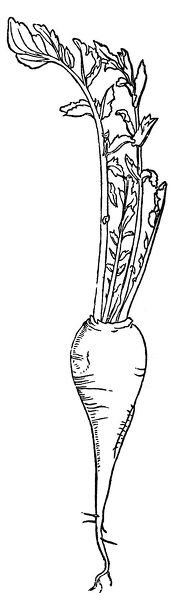

Illustration 68. Radish (Otto Brunfels, Herbarum Vivae Eicones, 1532)

So that the radish did not cause too much strife, precautions were taken to consecrate it. Radish consecration was traditionally done on the day of the festival of the Chair of St. Peter (February 22). This apostle was known for his choleric nature, which was brought to peace only through the gentle hand of the Lord himself. The European belief that St. Peter is responsible for the weather leads one to assume that the radish was under the protection of the thunder god Thor in pre-Christian times. Thor was also known to be very potent, earthy, and occasionally extremely hot tempered—he cast thunderbolts and lighting by throwing his mighty hammer.

The Healing Power of Radishes

The statement that radish “sweetens the blood” has some truth in it, as it affects the acid-base balance of life’s precious fluid. A stressful lifestyle together with a diet that contains too much sugar can lead to an increase in the carbon dioxide level in the blood, making it slightly acidic; this in turn can lead to burgeoning health issues. The black radish in particular helps to raise the pH level of the blood to its normal balance of 7.4.

Illustration 69. Radish in blossom

This pungent taproot has been prominent in traditional folk medicine since early times. The juice is rubbed into the scalp to vitalize the hair and make it grow. Radish seeds are cooked into a brew to counteract mushroom poisoning. Peasant dairy farmers use the crushed leaves to heal cows’ udders. Radish slices are placed on corns to soften them. An effective syrup to treat a chronic cough or bronchitis was made from radishes: a hollowed-out radish was filled with honey or sugar water and let stand for about ten hours, after which the syrup was taken a spoonful at a time. Radish juice rubbed on the skin helped restore a rosy glow to a pasty, sallow complexion. (In India there is also a cure made of ground radish seeds to help against leukoderma.) All of the stone ailments (calculosis)—gall, kidney, and bladder stones—were treated with radish juice. In particular, English herbal doctor Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) prescribed the juice mixed with wine for gallstones.

The radish is also cherished in India, where it is called “muli” (root); the word is also found in the Muladhara chakra, the “root” chakra. Indian hepatitis patients are given radishes, especially radish juice. As in traditional European healing lore, the juice is mixed with honey and salt for coughing and lung ailments. Ayurveda prescribes radish juice for urinary retention and painful urinating; for lithiasis (stones and gravel) one cup of radish juice daily is prescribed for two weeks.

Modern phytotherapy confirms most of the traditional uses of radish for healing. It is good for keeping a base milieu in the intestines and improves intestinal flora. The nineteenth-century Bavarian herbalist Sebastian Kneipp recommended eating it without salt. Its high potassium content makes radish into a diuretic, a desiccating agent for those with gout and rheumatism. It’s also good for a cold because it dissolves mucus and has an anti-inflammatory effect on the mucus membranes in the nose, sinuses, and throat. And as a tonic for the liver and gall bladder it is hard to surpass.

Radish Customs and Use Around the World

In earlier times—and to a degree today—gardeners carefully observed sowing times. It was believed that radishes sown on certain days—St. Kilian’s Day (July 8), St. John’s Eve (June 23-24), and Corpus Christi (celebrated 60 days after Easter Sunday)—would thrive especially well. If sown when the moon is in Aquarius or Pisces they would be juicy; in Sagittarius they would shoot into flower; in Cancer or Capricorn they would grow lots of small roots; and in Aries they would taste especially strong. The Pennsylvania Dutch chant while sowing: “As long as my arm, as thick as my leg!” If the radishes developed long “tails” it was thought a strong winter was about to come.

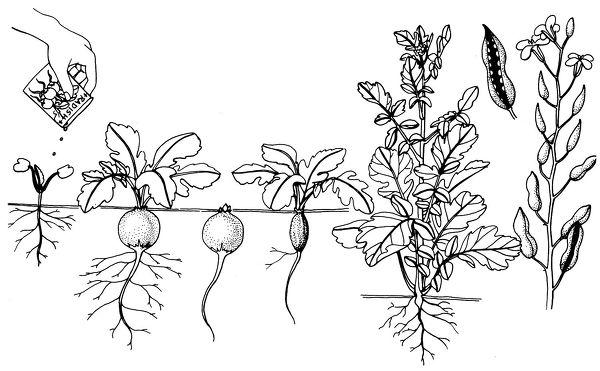

Radishes are cultivated all over the world. European settlers brought the radish to North America, where it was quickly picked up by the Native Americans. Since that time gardeners distinguish between the hardy, fall kinds that keep well and the summer kinds, which are consumed immediately. In Europe there are some twenty different kinds of both radish types. Small, red radishes are a relatively new cultivation that originated in Italian Renaissance gardens before spreading throughout eighteenth-century Europe. These small red radishes are actually not even roots—they are thickened root crowns (hypocotyl); the actual root is the small thread or tail below the crown.

Illustration 70. Radishes in their biennial growth period (illustration by Molly Conner-Ogorzaly, from B. B. Simpson and M. Conner-Ogorzaly, Economic Botany, 1986, 217)

Eastern Asia knows an abundance of radish varieties. In China and Japan the roots are eaten both raw and cooked, the leaves cooked as a vegetable. Varieties with seeds especially rich in oil (oilseed radishes) are used to make nutritional and lamp oil. Original China drawing ink is made from the soot of the flame of radish oil. Then there are edible radish seed pods, which are eaten in salads or as a vegetable. When my red radishes go to seed, I add the delicious pods to mixed vegetables in the wok.

The biggest radish is the mild Japanese daikon, which is cooked as a vegetable, used as animal fodder, and pickled like we pickle sauerkraut. And as they can grow up to three feet long and weigh up to fifty pounds, it is no wonder they are a symbol of wealth in Japan.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Radish seeds sprout quickly. Like alfalfa, cress, or mung beans, they are also good for sprouting in winter in dishes as a source for vitamins. For spring cultivation the seeds can be sown right in with carrots, as they are good row markers and are harvested long before the carrots need the space. Fall radishes are sown about sixty days before the first frost, so they will mature during cooler weather. Watering during any late summer heat spells will help cut their bite. Note that they will shoot to seed once it becomes too hot for them to thrive. (LB)

SOIL: As taproots, radishes prefer loose, sandy loam that is free of obstructions. And just as for carrots and parsnips, the soil should be well-composted—just not to the depths needed for the longer taproots.

Recipe

Radish-Grape Salad with Pumpkin Seeds ✵ 2 SERVINGS

SALAD: 2 black radishes (or a bundle of red ones) ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) red grapes ✵ 1 ounce (40 grams) pumpkin seeds ✵ SAUCE: 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar ✵ 3 tablespoons olive oil ✵ some fresh lovage ✵ 1 ounce (40 grams) raw pumpkin seeds, chopped ✵ honey ✵ sea salt ✵ white pepper

Grate or slice the radishes in thin slices. Put in a serving bowl. Cut the grapes in half and add to the bowl. In a separate small bowl mix the vinegar, olive oil, and lovage. Season with honey, salt, and pepper to taste. Pour over the radishes and grapes, tossing until evenly covered. Sprinkle with the pumpkin seeds and serve.