A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Pea (Pisum sativum)

Family: Fabaceae, Leguminosae, or Papilionaceae: bean, legume, or pea family

Other Names and Varieties: English pea, garden pea, Mange tout, snow pea, sweet pea

Healing Properties: helps prevent appendicitis, lowers cholesterol, can prevent conception, strengthens the immune system (ideal for cancer diet)

Symbolic Meaning: dwarf food, fertility, food of the dead,

Planetary Affiliation: Venus

The pea deva, the spiritual entity that shows itself in the form of a pea plant, is a pronounced friend of humanity. Pea seeds, along with vetch, wild pistachios, almonds, and various wild grains, numbered among the foods gathered by Mesolithic foragers in the Near East and west Asia. When the first tribes became sedentary some ten thousand years ago, this bean family member crept into the very first emmer and barley fields as a weed; soon it became a field crop on its own, turning into a valuable source of protein for humans and animals. The pea plant migrated up the Danube Valley into northern Europe with the swidden farmers and was cultivated at the time of the Linear Pottery Culture, the culture of the earliest central European agriculturalists. Because the pea, like all legumes, binds nitrogen with the help of rhizobia, it greatly enhanced soil fertility. Thanks to this plant these matrilineal cultivators were able to remain longer in one place before soil exhaustion led to decreasing harvests, forcing them to slash and burn a new section of primeval forest. The peas were eaten cooked into a thick soup (peas porridge), which, alongside grain porridge, was a mainstay for these tribes.

Today’s tender sweet peas (sugar peas) were yet unknown—not to mention snow peas. It was not until the seventeenth century that Dutch gardeners began to cultivate and market sugar peas, which are eaten unripe. Fresh sugar peas, which were incredibly expensive, were a new sumptuous delicacy, the absolute fashion among the wealthy. The queen of the French “Sun King,” Louis XIV, is recorded to have complained, “The young princes want to eat nothing but peas!” These popular tender peas were also introduced to North America, and Thomas Jefferson had them grown on his estate.

Illustration 57. Garden pea

Over time a lot of lore, superstitions, and rituals accumulate around such an important and old cultural plant. Ultimately, as small as it is, the pea came to play a more central role in European folklore and fairy tales than did any other vegetable. More than a few fairy tale heroes won both a princess and a castle with its help. As peas porridge is said to be a favorite dish of the wee folk, dwarves, and good house spirits, in order to please them a small bowl of it was traditionally placed in a dark corner of the house on Christmas Eve.

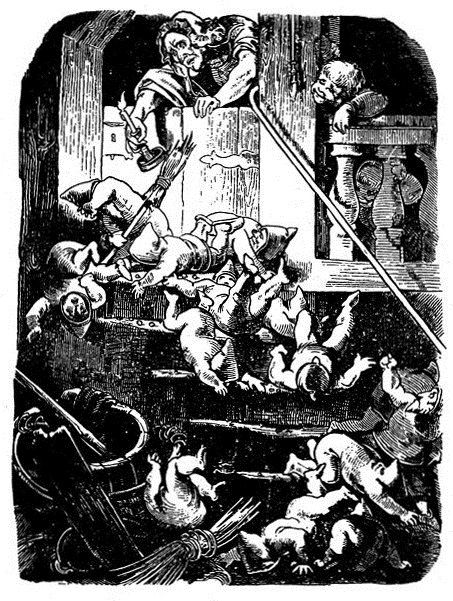

According to the German fairy tale “The Fairies of Cologne,” the wee folk used to come secretly in the night to relieve those sleeping of much of their unpleasant work. They helped with carpentry, sewed, baked bread, washed clothes, cleaned, and swept. They would probably still do this to this day had it not been for a curious tailor’s wife who thought she’d have no peace until she’d find out what they looked like. Toward midnight the nosy woman tossed a bucket of peas on the steps and lit a lantern; lo and behold, there she caught sight of the wee folk stumbling and tripping over the peas in their hasty flight. After that incident the helpful dwarfs left the city of Cologne forever, leaving the people to do their work themselves. The story is meant as a warning for all those who pry into nature’s secrets out of mere curiosity; or, as e. e. cummings put it, the tale speaks to the “naughty thumb of science” prodding sweet nature. Just like the fairies of Cologne, the ethereal beings that work wonders in nature shy away from rude curiosity and cold intellect.

Illustration 58. Curiosity drives off the fairies of Cologne (nineteenth-century sketch)

In the original Brothers Grimm fairy tale “Cinderella,” doves take the place of helpful fairies. So that Cinderella would miss the ball given by the prince, her stepmother commanded she do an impossible task: sort out the good peas from the spoiled ones; but with the help of the doves, she is able to finish in time and attend the ball, where of course she wins the prince. And then, let’s not forget, there is the story of the princess and the pea.

Folk tales also tell of nasty dwarves who plunder pea fields at night, breaking open the pods and trampling the bushes. In order to stop this naughty behavior, it is advised to go into the field before midnight and beat the ground around the pea beds with switches and whips. In doing this there’s a chance one may knock off one of the dwarves’ invisibility-rendering magic hats; this accomplished, there’s a good chance to grab one of the tiny plunderers and force him to exchange the hat for a gift, such as a divining rod for finding hidden treasures. On the other hand, it might be wiser to let the dwarves continue enjoying the peas in exchange for a rich harvest that they won’t trample.

Land cultivators the world over have historically acknowledged the importance of ritually feeding the dead, and this custom is even today especially strong in China, Africa, and Latin America. Understandably, they give these departed ancestors foods they had especially enjoyed during their lifetimes; in return, the living hoped their fields would be blessed with good harvests, their animals with good health, and, of course, their descendants with good fortune. In early Egypt (twelfth dynasty, 1900 BC), among the foods offered to the dead was the unpretentious pea. Gypsies—who originated from the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent—offered peas for the departed; Europeans offered peas and peas porridge. Indeed, despite scientific enlightenment, despite the Church’s warning against this sinful superstitio, this excessive religious observance, the practice continues in the European countryside to this day. Some prevailing beliefs: those who eat or cook peas (even only the husks) during the Holy Week will soon have a corpse in the house—perhaps their own; whoever sits on a pillow made of pea straw on New Year’s Eve will soon die; anyone who eats peas during the twelve days of Christmas will get boils on the arse or will become hard of hearing—or their chickens will stop laying eggs. Or, there’s always the possibility, as is said in Germany, that grim old Bertha—a reminiscence of the archaic European goddess of death and rebirth—will cut open the offender’s stomach and stuff it with pea straw.

What is the deeper meaning of these winter solstice taboos of foodstuffs? During this sacred time peas are food for the dead and taboo for the living. It was general knowledge that the ancestral spirits visit during the twelve days of Christmas. Since they entered the house through the chimney, the hearth must be very clean, with a bowl of peas, hemp seeds, or millet porridge placed near it in offering. In Bohemia until only recently it was a custom to pour a portion of peas porridge at all four corners of the living room, making the sign of a cross with each pouring; though it was said to be “for the mice,” it was mostly likely originally meant for the ancestral spirits.

Nearly all cultures know the custom of the funeral feast: the final farewell meal in which the departed loved one participates “in spirit” before beginning the long journey into the hereafter. In Mecklenburg, Germany, peas porridge is part of the traditional funeral feast. In Freiburg, Germany, it was the custom to serve peas porridge to the beloved departed at midnight during the wake.

The traditional cultures, such as that of peasant Europe, did not experience time as linearly as we do, but as a cycle, as a revolving wheel. In the yearly cycle, midsummer and midwinter stand opposite to each other. Peas are considered off-limits during the winter solstice festival, they are heartily enjoyed in the summer. While eating peas at Christmas may be punished with blemishes of the skin, their consumption during midsummer is recommended for healing such ailments. Indeed, in Swabia, Germany, peas cooked in the St. John’s midsummer fire are believed to have particular healing power.

Most traditional peoples believe that ancestors send fertility from the other realm. So for the cultures that make offerings of the pea, it’s not surprising that the small vegetable is associated with fertility magic in both house and barn. In the twelve days of Christmas, the farmer’s wife mixed peas into chicken fodder so the hens would produce plentiful eggs and the rooster would maintain virility and continue to crow vigorously. Baltic peasants would add peas to the pig food on New Year’s Day for similar reasons. Another custom was to walk around one’s orchard and knock on the tree trunks with a sack full of peas; the idea was that there should be as many fruits on the trees at harvest time as there were peas in the sack.

It is only logical that what works in the barn and orchard must also work for people. In many places peas played a major role in wedding festivals and festivities surrounding birth. Peas and cereal grains were thrown over the bride, or peas were put in her shoes. In some places peas are thrown against the windowpanes during bachelor parties or eve-of-wedding fests. And while modern people may shake their heads about such “silly” superstitions, who of us truly knows the extent to which the power of visualization can subtly influence ethereal realms? If nothing else, faith in such rituals frames the actions we take in our daily lives in the process of working toward our highest goals—the perseverance of which can make all the difference.

We’ve discussed how agricultural peoples of yore imagined the life force evident in both plant growth and the animal drive as that of a natural deity or daemon. This entity, whose brimming strength makes it hard to tame, was honored and celebrated in so-called “mystery dramas” at sacred points in the yearly cycle. In the European countryside this force of nature was personified as a “grain bear,” “corn mother,” “harvest queen,” “field wolf,” or “stag”—or as a “pea bear.” In the winter nights, especially during the Christmas period or during Lent, this daemon was represented by a young man dressed in pea straw. Like a dancing bear, the young man would be led by a “bear trainer” on a chain through the village. The young man acted wildly, grumbling and growling at the young women he tried to snatch—to their delight. In Thuringia during Lent a hairy “bear” ambled through the villages begging for alms. In the Rhineland on Ash Wednesday the pea bear rampaged through the streets; to increase fertility, the women tried to pluck some of the pea straw from his coat to put under theirs hens’ nests, or under their own beds. In some locales, the pea straw worn by the young man was later burned in the traditional public spring bonfire—part of the effigy of “old man winter” or the “old winter witch” that was set aflame. Folklorists recognize remnants of archaic sacrificial rites in these practices. As the Oxford scholar Robert Graves (1895-1985) claimed, in the late Neolithic era potent male animals or even young men were sacrificed to the earth goddess.

From the beginning of its influence the Church tried to ban such old beliefs and customs. For example, at the Synod of Liftinae in Belgium in the year 743 AD, the “Indiculus Superstitionum et Paganiarum (Small Index of Superstitions and Paganism)” listed prohibited pagan customs such as the “bawdy festivals in February.” Nonetheless, many of the rituals managed to live on unabated even into our modern times.

In the autumn, while the cutters harvest the fields, the vegetation daemon flees into the last sheaf of grain. This sheaf is then decorated and carried triumphantly on the harvest wagon through the village. In some places the one who bound this last sheaf is wrapped in pea straw and decorated with horns; in him, the “pea bear” momentarily takes on visible form.

For the pre-Christian Germanic peoples the pea bear was seen as an incarnation of strong, hairy, thunder god Thor (Anglo Saxon Thunar, Old High German Donar), whose nickname was “Osborn” (Scandinavian Asbjørn), which means “divine bear.” When Thor, the favorite god of the country folk, throws his lightning hammer across the sky in a thunderstorm, the fields turn green. In northern Europe, a Thor’s hammer was placed into the lap of the bride at the wedding to ensure she will be as fertile as the fields. Until recently in eastern Germany the “pea bear” accompanied the bridal procession, certainly a remnant of archaic fertility magic. In many areas it was customary to eat a porridge of peas with bacon on Thor’s day—Thursday. Even today in Swabia, Germany, peas porridge is eaten on Thursdays during the advent time, the four weeks leading up to Christmas, so as to ensure money won’t run out in the coming year. (The divine bear, as a harvest god, is thought of as rich.) In Swabian custom, during the last three Thursdays of advent one must throw dry peas against the windowpanes. Local priests claim that such is a sign of the “coming appearance of the savior,” but it is more probable that the peas are considered the roaming spirits that bring fertility. The patter reminds of the hail that often announces Thor’s presence.

The pea, thus, was not only popular as an important cultivated plant; it was essentially believed to be divine. For medieval Christians each pea has the signature of the sacramental chalice engraved in it—it is the navel of the seed. Of course, the pea had to have its own patron saint: St. Notburga of Tyrol (Austria). Patches of wild peas still grow in the area where she once lived— because, it is said, she often fed the poor with peas porridge.

Peas porridge hot, peas porridge cold,

Peas porridge in the pot, nine days old.

—Traditional English nursery rhyme, ~1760

The Pea As a Healing Plant

It would seem that such a revered plant would also play an important role in healing lore, but that is not the case. Nursing mothers traditionally applied peas porridge to treat their nipples when they were sore from nursing—but this was probably nothing more “sympathetic medicine,” as peas resemble taut nipples. Similar “sympathetic magic” was practiced when the birth pains began. Peas were put over the fire; when they began to cook—according to the belief—the birth would take place. Peas were also said to cure warts. The unsightly verruga was rubbed with a pea, after which it was put in a satchel and thrown out; whoever later picks up the bag by chance will get the wart. (This cure is considered even more effective using a pea stolen from a neighbor’s field.)

It was not until the twentieth century that the pea revealed its hidden medicinal properties. Peas are good for diabetics; they can lower harmful LDS cholesterol and, to a small degree, blood sugar levels. They are also helpful in cancer and AIDS diets because they contain protease inhibitors, which trap oxygen radicals and reduce inflammation. As a result of British research in 1986, it was discovered by chance that pea dishes help prevent appendicitis.

Dr. S. N. Sanyal, a biophysicist from the University of Calcutta, “discovered” that the pea, long considered a symbol of fertility, is actually rich with contraceptive substances. It contains m-Xylohydroquinone, which dampens fertility by intervening in the production of progesterone and estrogen. Dr. Sanyal showed that female fertility was reduced by up to 60 percent; for males the sperm count was substantially lessened. But such was, indeed, merely scientific verification of what Asian medicine had already long known; Indian women have traditionally cooked a soup out of pea pods in order to delay conception. Interestingly, in Tibet, where peas are a major source of nourishment, the population remained stable over hundreds of years. (Carper 1988, 180) Note, however, that this is not to say that pea extract can effectively replace the near-perfect efficacy of the birth control pill.

Why does the pea produce sexual hormones, as do other pulses? Ecologists presume that via these hormones such plants practice birth control on their natural predators. How so? At times when the climate is too cold or too dry for optimal growth, the plants produce these hormones in abundance so as to reduce the chance of being consumed out of existence. But during optimal conditions, when they themselves are abundant, they produce such small amounts of these fertility-reducing hormones that they have little or no influence on their predators.

It seems that the deva of this particular philanthropic legume still communicates actively with the more sensitive among us. It was through the pea that Augustinian monk Gregor Mendel (1822-1884) discovered the laws of genetic inheritance. For years in his cloister garden in Brno, Moravia, he tirelessly crossed smooth yellow peas with wrinkled green ones, recording the results. Though few showed interested in the monk’s obscure hobby at the time, his pea cultivation research has become the cornerstone of contemporary genetics studies.

The famous Findhorn Garden in northern Scotland owes its status to the pea deva. Dorothy Maclean, a “highly sensitive person,” got her first message from plant devas through the pea plant. That it was this ancient cultigen that “talked” to her is no coincidence: she had always, since childhood, cherished the plant, loving how it grows, how it flowers and smells. This empathy, rather than the scientific experimental method, brought her into contact with what she called the “soul of the pea kingdom.” The message she received: if humans open their hearts to plants, then miracles such as seen in Findhorn can happen.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Few garden crops are as highly prized as peas, which can be planted in spring as soon as the soil can be cultivated. A few light frosts will not hurt them. The seeds can be treated with a bacterial inoculant so that they produce more nitrogen. Because the pea is a trailing plant, it appreciates a trellis to climb on. As soon as the plants are big enough to climb they should be mulched to keep the roots cool. Sugar peas should be harvested when the pods are full but not yet hard. Snow peas (edible pod peas) should be picked just as the peas inside begin to form in the pod. (LB)

SOIL: In order to grow well peas like loose, sandy soil that is well composted and well fertilized with natural fertilizers.

Recipes

Cold Pea Soup with Mint ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1 pound (455 grams) unpeeled early potatoes, cubed ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ 1 pound (455 grams) fresh peas ✵ black pepper ✵ herbal salt ✵ 1 pinch vanilla powder ✵ dab of honey ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) cream (18% fat) ✵ fresh mint leaves (as garnish)

Simmer the potatoes in the vegetable broth for about 20 minutes or until tender. Add the peas and simmer for about 10 minutes. Let the soup steep for about 15 minutes. Blend with an immersion blender until smooth. Transfer to a covered container and chill in the refrigerator for about one hour or until cold. When cold, transfer the soup to a serving dish. Season with the vanilla, honey, salt, and pepper to taste. Mix in the cream. Garnish with mint leaves.

TIP: This soup pairs nicely with croutons freshly roasted in olive oil.

Pea Salad with Garlic Croutons ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1 pound (455 grams) fresh peas (without pods) ✵ ½ pound (225 grams) tomatoes ✵ 2 onions, finely chopped ✵ 1 bunch parsley ✵ bit of lovage ✵ bit of honey ✵ 1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar ✵ 3 tablespoons hazelnut oil ✵ sea salt ✵ pepper ✵ 2 slices bread, cubed ✵ 4 to 8 garlic cloves, chopped ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil

In a medium-large serving bowl mix the peas, tomatoes, and onions. In a separate small bowl, mix the parsley and lovage with the vinegar. Add honey to taste. Pour this mixture over the vegetables until they are evenly covered. Season with sea salt and pepper to taste; let rest for 10 minutes.

Fry the bread cubes and the garlic in the olive oil at a low temperature until golden brown. Let cool for a few minutes before sprinkling them over the salad.