A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

The aim with this book is to provide the reader with a holistic view of the vegetable residents of our gardens. To do this we’ll want to consider vegetables in all aspects: their botanical peculiarities, their family membership, the symbology and meaning bestowed upon them in different cultures, the myths and stories concerning them, and their healing potential and general traditional uses. We will do this in parts, starting with common vegetables—from asparagus to Jerusalem artichoke to tomato—before discussing the forgotten, rare, and less-known: both of vegetables (such as burdock, Good King Henry, and skirret) and of lettuce greens (such as miner’s lettuce, purslane, and rampion).

For readers fortunate enough to call a vegetable patch their own, I have included invaluable Garden Tips from my friend Larry Berger, a pioneer organic gardening expert with many years of experience. His advice is labeled with an “LB”; those with no label are my own. For those who like to cook, another friend of mine, Swiss gourmet cook Paul Silas Pfyl, has created some novel recipes that perfectly bring out the spirit to be found within each vegetable or lettuce—from both the common as well as the lesser-known varieties.

![]()

Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis)

Plant Family: Asparagaceae: asparagus family; formerly Liliaceae: lily family

Other Names: garden asparagus, sparrowgrass

Healing Properties: cleanses blood, especially for those suffering from rheumatism or bladder, kidney, or heart ailments; rejuvenates energy; promotes urination (diuretic)

Symbolic Meaning: nobility, wealth, refined eroticism; signature of the goddess of love: Aphrodite/Venus, Kamadeva

Planetary Affiliation: mainly Venus and Mars; also Jupiter

In northern Europe asparagus season is a very special time of year. Easter and Pentecost (Whitsuntide), which are celebrated as joyously as is Christmas, would not be complete without a dish of buttered asparagus. As such there are many recipes highlighting this culinary delight.

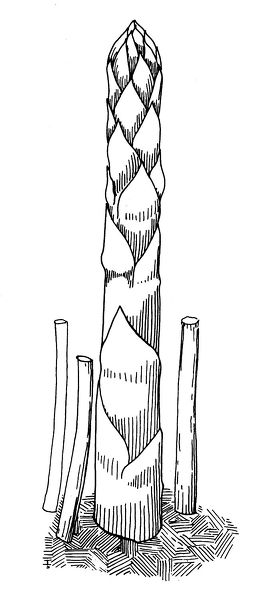

Illustration 8. Asparagus (illustration by Molly Conner-Ogorzaly, from B. B. Simpson and M. Conner-Ogorzaly, Economic Botany, 1986, 120)

In early spring, when fresh asparagus begins to appear in the markets in northern Europe, everyone knows that warmer days are just around the corner. This vegetable somehow bears within it the promise of warm summer days after the long, cold winter. The way that asparagus has always been eaten—and in some cases is eaten still—surely makes it what anthropologists call “ceremonial” food: food eaten in a special context. The delicate, fast-growing spring shoots of this Liliaceae family member fit perfectly to the image of nature finally awakening in the spring and to the Easter festival when the Savior was “resurrected.” For the Easter dinner asparagus is usually served with ham, and for good reason; while their flavors do complement each other, there is an archaic symbolic element to the pairing as well. Pigs were once considered a symbol of life, joy, and fertility for the Celtic-Germanic-Slavic northern Europeans. On certain special occasions, Germanic tribes sacrificed a pig or a wild boar for Freyr, the phallic god of fertility and brother of the beautiful goddess Freya. The celestial twins were believed to ride over the countryside in a wagon in the spring, Freya all the while strewing flowers from the carriage. In pre-Christian times people celebrated an orgiastic May festival during the time of the full moon. They raised the phallic maypole, danced rounds, and indulged in ecstatic sensual love. After the Christianization of Europe, this festival was changed into Whitsuntide or Pentecost, celebrating the Holy Spirit who descended upon the people such that they spoke in tongues. For this reason, the Pentecost Sunday meal usually consists of cooked (cow) tongue served with asparagus.

This lacy plant of the lily family is definitely an aristocrat. Cookbooks praise it as the finest of vegetables, and it has been lauded throughout the ages. Modern-day plant expert Fritz-Martin Engel reports: “Pharaohs, emperors, kings, generals, and great spiritual leaders, princely poets such as Goethe and gourmands like Brillat-Savarin—all of them ate and eat asparagus with great enthusiasm.” It follows that old astrological herbal doctors saw in asparagus the signature of the god Jupiter, lord and enjoyer of all sensual pleasures.

For the ancient Egyptians asparagus was a sacred food; for this reason they included it in offerings to the gods. Archeologists have found valuable dishware during excavations at the Pyramid of Sakkara (Saqqara) that had food traces clearly identifiable as asparagus. Bundles of asparagus tips—alongside figs, melons, and other sumptuous foods—were also found in the graves of rich Egyptians buried some five thousand years ago. At around the same time in China, honored guests were treated to a relaxing asparagus footbath upon their arrival. Ancient Greeks harvested wild asparagus; the ancient Romans went further, having developed the necessary painstaking garden methods to cultivate this vegetable. Caesar Augustus is supposed to have been especially fond of asparagus—perhaps because the shoots were regarded as one of the greatest aphrodisiacs—and what the emperor does, everyone else does. And historical chronicles report that Emperor Charles V (1500-1558), the ruler of the Habsburg Empire, paid an unexpected visit to Rome during the time of fasting. Since there were not many supplies at hand at such short notice, the cardinal in charge had an idea that saved the day. He had the cooks prepare three different asparagus dishes, served on three different perfumed tablecloths along with three different exquisite wines. It is said that the emperor praised these delicacies for years on end. Asparagus dishes were also cherished at the court of the “Sun King,” Louis XIV. Whoever wanted to win over Madame de Maintenon, the king’s second wife, only had to bring her a new asparagus recipe. She wrote all of the recipes into a book; asparagus soup à la Maintenon is still common knowledge for gourmands.

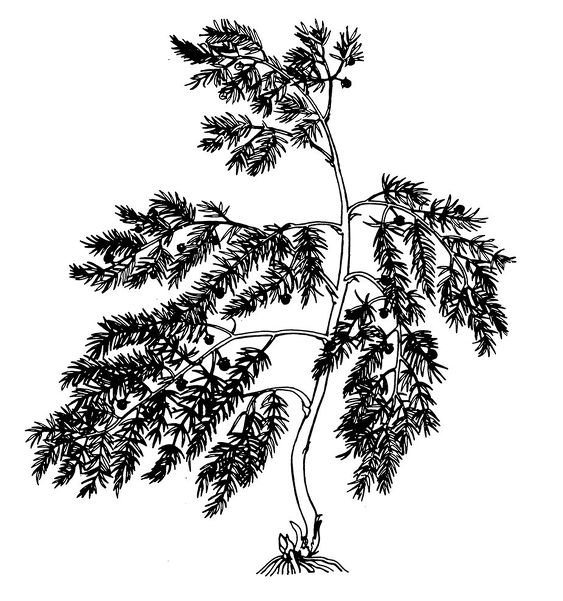

Illustration 9. In eastern Europe icons are decorated with feathery asparagus fronds (illustration by Molly Conner-Ogorzaly, from B. B. Simpson and M. Conner-Ogorzaly, Economic Botany, 1986, 236)

Much of the aura of asparagus concerns its reputation as a rejuvenating aphrodisiac. Indeed, backing this description is the belief that the fast-growing, phallic shoots will increase sexual desire and potency. The ancient Greeks ascribed asparagus to the goddess of love, Aphrodite. The Boeotians made wreaths for brides out of asparagus fronds. The poet Apuleius, author of The Golden Ass, is supposed to have won over the heart of the wealthy widow Pudentilla with a love potion containing asparagus, crab tails, fish eggs, dove blood, and a bird’s tongue. (The marriage earned him a court case for witchcraft, but he was acquitted.)

Though this fine vegetable was placed under the rule of Jupiter, it does not reside there exclusively. Medieval doctors, not surprisingly, also attributed it to Venus, the planetary goddess who rules over urinary and sexual organs. Consequentially, these doctors prescribed cooking the root in water or wine and drinking it “to increase semen” and stimulate libido. (Galenic humoral doctors also prescribed the plant for “obstructions of the liver, spleen, and kidneys,” as well as for kidney stones since it was considered “dilutive, diuretic, and dividing.”)

Asparagus was regarded as a sex tonic in other cultures as well. The Hindus ascribed it to their “cupid,” Kamadeva, who could help a beautiful maiden, young Parvati, beguile even the highest ascetic god, Shiva; this he did by aiding Parvati in distracting the ash-covered ascetic god just long enough for him to fall in love with her. Though he later married Parvati, the extreme yogi Shiva was furious at having his deep meditation interrupted, and burned Kamadvea to ashes with his fiery third eye. Shocked, the goddesses begged Shiva to bring the god of love and sensual desire back to life. Shiva finally conceded and revived Kamadeva, but as he no longer had a body he became even trickier, especially when invisibly shooting his honeyed arrows into hapless hearts.

Traditional Medicinal Use

In the Indian Ayurveda medical tradition, although wild asparagus (satavar or satamuli; sat = one hundred, muli = roots) is also used as a heart and brain tonic, it’s generally considered a healing plant for sexual ailments and infertility, especially in that it’s thought to increase ojas, general life energy. The juice of the roots is cooked with clarified butter (ghee), lemon juice, honey, long pepper (Piper langum), and milk to create an aphrodisiac that increases semen, increases mother’s milk, and tones the uterus. In a similar tradition, Muslims cook the roots (safed musli) in milk as a substitute for salep, the famous elixir made of orchid bulbs for increasing masculine prowess and for “thickening and increasing semen” (de Vries 1989, 303). And in China, asparagus (known for over five thousand years by the name Tien men Tong) is used as a diuretic and expectorant. Asparagus came to America with the European settlers; it escaped from gardens to become a rampant wild plant, an invader growing along roadsides and railroad tracks.

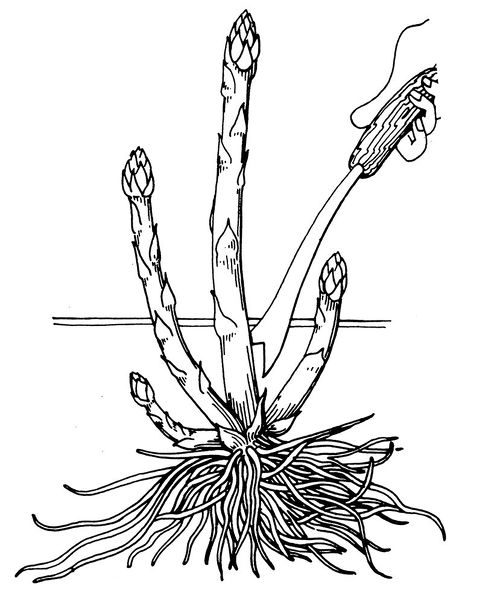

Illustration 10. Aristocratic vegetable asparagus (illustration by Molly Conner-Ogorzaly, from B. B. Simpson and M. Conner-Ogorzaly, Economic Botany, 1986, 236)

In the seventeenth century asparagus began to be cultivated in central Europe as a vegetable and a medicinal plant; from that time forward it finds mention in herbal books. In the apothecaries the root was called “officinal”—from which comes the botanical name officinalis—which means it was in the officinarum, the workroom of the apothecaries. This also means that asparagus root was recognized by the Galenic doctors as a proper medicine, specifically for “blood thinning,” for “hip pain” (rheumatism, sciatica), hepatitis, kidney stones, and urinary disorders. Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501-1577), the personal physician of the Habsburg emperor, wrote in his 1544 herbal book: “Asparagus makes men have pleasant desires,” a belief also shared among the simpler folk, as a tongue-in-cheek Swabian folk saying goes: “The pastor knows very well why he has asparagus in his garden.” In Transylvania it was known as “spindle in the pants.” In Styria, Austria, the former home of Arnold Schwarzenegger, wine with asparagus seeds was prescribed for infertility.

In modern phytotherapy, asparagus is still considered to be an effective diuretic. Preparations from the rootstock are made for renal gravel, edema, arthritis, rheumatism, gout, cardiac insufficiency, and liver and spleen ailments. As such, it’s effective for diabetes, heart ailments, and lesser kidney ailments.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: Given how difficult it is to grow, asparagus is understandably a costly deluxe vegetable. Each asparagus plant—like a typical aristocrat—needs much more room than do other ordinary vegetables. Because the plant is originally from the eastern Mediterranean, it also needs plenty of sun and warmth. Asparagus grows best in any kind of environment where vineyards thrive. From the sowing of the seeds, which only reluctantly germinate, until the first harvest, four whole years have to pass. In the first year, in “kindergarten,” the seeds grow into small plants with buds and thick outrunner roots that look like tarantulas. Each of these spider-like formations should be planted about two feet apart from each other and almost a foot deep. They should then be well covered with sand and humus. The best fertilizer is composted dove or pigeon dung—I can testify for this out of my own gardening experience. (Note that doves are also under the rule of Venus.) At this stage, it is important to make sure the beds remain free of weeds.

Not until three years have passed will this plant of the Liliaceae family finally blossom. Its greenish white blossoms develop into coral red berries, which attract birds. The seeds of the berries, which pass through the birds undamaged, have been thus distributed throughout America, South Africa, and Australia. The red berries hint that Mars, Venus’s lover, is also in the plant signature. Occultists and advanced Harry Potter adepts are mindful to collect the berries in the new moon. Magister Botanicus, the classic German handbook on plants, reports that in inside circles the berries are sold as “Ferrari testosterone.”

In the fourth spring the first harvest begins. And though it is tempting to want it all, it is important to not be too greedy; be sure to leave at least half of the shoots so the plant can strengthen with the sunlight. By summer the shoots develop into four-foot-tall, beautifully delicate fronds. In eastern Europe these fronds are used to decorate religious icons. In Livonia asparagus is called “God’s plant”; in Lithuania it is called “sacred plant.”

Asparagus can usually be harvested for up to fifteen years before it gets too worn out—at which point one can begin again with a new garden bed and new plants.

SOIL: Though it takes a few years to establish a producing asparagus bed—even when grown from roots rather than seeds—if cared for properly an asparagus bed can last for up to fifteen years. The plant prefers a loose, sandy, and somewhat alkaline soil that is also rich in humus, yet it will do well in heavier soils as long as they drain well. Select a sunny corner of your garden, one with rich, deep soil. And note: the heroic measures formerly taken to plant asparagus on soil mounds in eighteen-inch-deep trenches are no longer considered necessary; roots (of the young plants) planted two to eight inches deep do just as well. These planting beds should be well prepared with plenty of powdered limestone and well-rotted manure. Mulch the bed and wait a year before planting, which should produce your first two-to-three-week harvest. After five years, your harvests will likely last for up to ten weeks.

Recipes

Asparagus Dessert with Mallow Blossoms ✵ 4 SERVINGS

3 cups yogurt ✵ 1 pound green asparagus ✵ 2 tablespoons raisins ✵ 3 tablespoons honey ✵ 2 tablespoons ground hazelnuts ✵ 1 pinch saffron ✵ 30 mallow blossoms

Put the yogurt in cheesecloth (or a dishcloth) and drain for 12 hours at room temperature. Cut the asparagus into small wheels and steam until soft. Let cool. In a large bowl mix the drained yogurt with the raisins, honey, ground nuts, saffron, and the asparagus wheels. Garnish with mallow blossoms and serve.

Asparagus Tureen with Rhubarb Sauce ✵ 4 SERVINGS

TUREEN: 2 pounds (905 grams) green or white asparagus ✵ 1 pinch marrow from a vanilla bean ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ 7 tablespoons cheddar cheese, grated ✵ 2 eggs, plus 2 egg yolks, whisked together ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) cream (18% fat)

RHUBARB SAUCE: 1 cup rhubarb, cubed ✵ 2 tablespoons butter ✵ 1 tablespoon honey ✵ 1 tablespoon apple vinegar ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) sweet basil leaves

TUREEN: Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Steam the asparagus with the vanilla and herbal salt until tender. Set aside 8 asparagus spears. Purée the remaining asparagus in a large bowl and pepper to taste. Cool for about 30 minutes. Once it’s cool, mix into the asparagus purée the cheese, eggs, egg yolks, and cream. Place the 8 asparagus spears in a 9 by 13-inch ovenproof dish. Cover the spears with the asparagus purée. Place the dish in a larger pan with sides higher than the dish; add water to the height of the contents of the dish. Bake in this water bath, covered, at 350 °F (175 °C) for about 40 minutes. It’s ready when golden brown on top. Transfer to a serving tureen.

SAUCE: In a medium pan sauté the rhubarb in butter until nicely blended, about 5 minutes. Add honey. Season with herbal salt and pepper. Add the vinegar and vegetable broth and let simmer for about 20 minutes. Stir in the basil and serve with the asparagus tureen.