A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Onion (Allium cepa)

Family: Amaryllidaceae: daffodil family; formerly Liliaceae: lily family

Other Names and Varieties: baby onion, gibbon, green onion, long onion, onion stick, precious onion, salad onion, scally onion, spring onion (in Britain), syboe, table onion, yard onion

Healing Properties: thins blood, lowers blood sugar levels, arouses desire (aphrodisiac), stimulates the heart (cardiotonic), strengthens the immune system (antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiviral), clears mucus (expectorant), promotes urination (diuretic)

Symbolic Meaning: sacred plant of Isis, goddess of the moon; menstruation, fertility; absorbs poison and disease; potent etheric life energy; poverty

Planetary Affiliation: moon, Mars

The onion is one of the world’s earliest cultivated plants. In the Neolithic period it was grown in India, China and the eastern Mediterranean. The Greek historian Herodotus (484-425) noted how an inscription on the Cheops (Khufu) pyramid in Egypt indicates the quantity of onions, garlic, and radishes eaten by the slaves who built it. And the Bible tells us how the Hebrews longed for the onions of Egypt as they trekked through the desert; such is, incidentally, the origin of the German expression “longing to go back to Egyptian onions”—longing for the good old days.

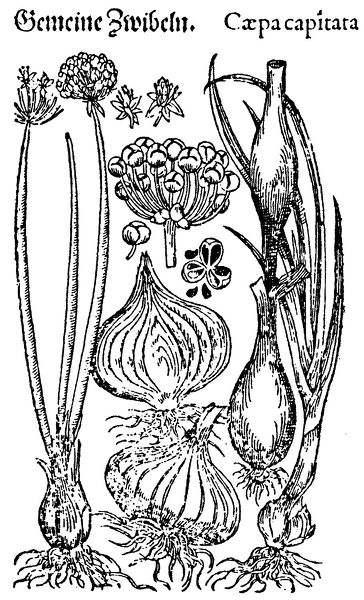

Illustration 52. Shallots and onions (Joachim Camerarius, Neuw Kreütterbuch, 1586)

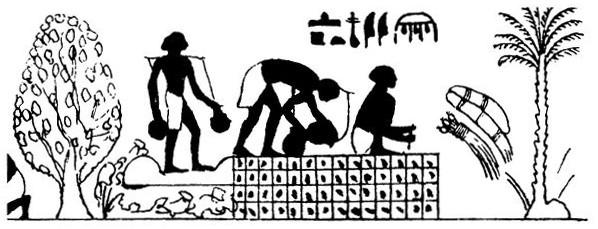

Illustration 53. Ancient Egyptians watering and harvesting onions (depiction in chamber tomb no. 3 in Beni Hasan; copy of the original by Percy E. Newberry, 1893)

In classical Roman times cultivated people avoided those who reeked of onions, and “onion eater” was a derogatory term. Nonetheless, Varro, a Roman contemporary of Caesar, wrote, “Our grandfathers were very decent people even though their words smelled of garlic and onion.”

The onion has historically remained one of the cheapest foods on the market; as such it has long been an ally to the poor, as both food and as an important healer—especially for those unable to afford a doctor’s visit. Even today it is still a super star among the healing plants used in folk medicine. Poultices made with finely chopped, steamed onions are successfully used for many ills, including sinus infections, abscesses and boils, lung inflammations, middle-ear infections, and tonsillitis. Swiss pastor and herbal healer Johann Künzle (1857-1945) subscribed to traditional usage when he announced: “chopped, steamed onions pull sickness out so strongly that they become black and smelly; the onions soak up the poison of the disease.”

Belief in the bulb’s ability to soak up poison and negative “radiation” was shared from England to eastern Europe. The English would hang a bunch of onions in the kitchen to “soak up bad luck,” and even wore an onion as an amulet or rubbed raw onion on the soles of the feet in order to draw sickness out of the body. In Bohemia and in the Erz Mountains, consecrated white onions were hung in the living room on Three Kings’ Day “because they attract and neutralize fevers.” Similarly, Dutch country folk would hang a linen satchel of chopped onions over a sick child’s bed.

From such practices, it was but a small step for the onion to be used apotropaically—as means of warding off dark magic. Onion was believed to keep at bay not only sickness and plague but also wicked witches, bad spirits, and vampires. Italian lore claims that carrying an onion in the pocket protects from the evil eye. Serbs would tuck an onion into the bosom of a young bride to protect her from any bad wishes envious neighbors might harbor toward her. And such superstitions regarding onions spread well beyond Europe. In India in times of cattle plague farmers hang red-painted onions on a rope across the village entrance. In China it was common to wear an onion “necklace” during a cholera epidemic. In many places it was considered a good omen for a convalescent to dream of an onion, a signal guaranteeing returning health.

One can certainly rely on onions to help cure a cold. Anti-inflammatory, expectorant, and sedative onion syrup (onion juice reduced in honey or sugar) is popular in many places for bronchitis or a persistent cough. This recipe is known in India as well as in America, brought from Europe by the Pennsylvania Dutch. For a runny nose Swiss natural healer Alfred Vogel (1902-1996) recommends onion tea—sliced onions brewed with boiling water and steeped, to be sipped throughout the day. Inhaling the steam of cooking onions is beneficial for colds as well; for headaches and fever a steamed, chopped onion poultice can be wrapped around the soles of the feet.

Folk medicine similarly recommends holding a hot onion poultice for fifteen minutes on muscles cramped with lumbago. Rheumatic joints, sciatic pain syndrome, and neuropathic pain—even insect bites and warts—can all be treated with freshly chopped raw onion. In a similar treatment, raw, salted onion slices can be wrapped on corns overnight.

And what does modern analysis say to all of this? It attests that the sulfur compound allicin—that which causes tears to flow when onions are cut—has an antiviral, antimicrobial effect. In addition allicin strengthens the immune system by increasing the activity of killer cells. It hinders cholesterol oxidation in the blood, thus protecting against arteriosclerosis. Regular “onion eaters” have better blood values; this is because allicin slows platelet adhesion and accelerates the dissolving of blood clots. It also hinders nitrifying bacteria and therefore the development of carcinogenic nitrosamines in the intestines. But the benefit to blood doesn’t end there; the phenolic acid and flavonoids in the onion also have a beneficial effect on the circulatory system, including lowering the blood sugar levels of diabetics. These research results confirm famous modern-day herbal healer Maurice Mességué, who advises that diabetes patients and heart patients include plenty of onions in their diet.

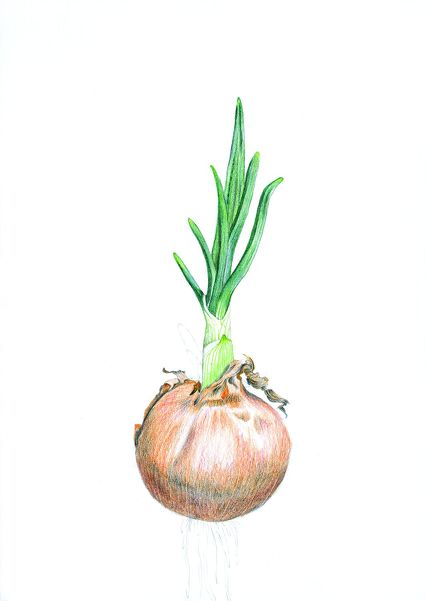

The onion, a triennial plant of the onion-garlic or allium genus, originates from the Asian steppes, an extreme climate to which it is completely adapted. In the moist springtime the small, marble-sized baby onions or “sets” begin to bud and start to soak up light and warmth into early summer. Later, when the weather becomes drier, the succulent, half-subterraneous bulbs—that is, the full-sized, mature onions—are formed. The following year these sprout and shoot into blossom and seed. In the meantime, in order to survive the dry, icy cold winter of the steppes, the bulbs store the watery life forces of the moon in their layered skins, enriching them with sulfuric glycosides. According to the alchemists of old, sulfur is a transporter of light and warmth. It is this combination of lunar water from the moon and fire energy from Mars that gives onions their extraordinary healing power.

Wild leeks and onions of various kinds are also to be found in the steppes of northern America, where Native Americans gathered them for both food and for healing. (Indeed, the name “Chicago” derives from a word of the Fox Indians that means “a place that stinks of wild onions.”) Just like their Eurasian counterparts, Native Americans used onions for insect bites, infections, and inflammations; they drew poison and pus out of carbuncles and abscesses with onion poultices or reduced onion syrup (a method particular to the Iroquois). To help heal colds and sinus infections, Black Foot Indians put onions on red-hot rocks and breathed in the caustic steam. Nursing Native American women drank onion tea so as to transfer its healing qualities to their infants in their milk.1

Onions have a long history in the folk customs, symbolism, and healing practices in India, China, and the eastern Mediterranean. For example, the Chinese symbol for “intelligent” (ts’ung) is the same as for “onion.” Chinese midwives traditionally touched the head of the newborn with an onion so it would grow to be intelligent.

Illustration 54. Onion (drawing from Hortus Sanitatis, 1491)

The onion was also a sacred plant in ancient Egyptian five thousand years ago. Onion bulbs were offered to the gods and placed into the hands, on the eyes, or on the genitals of mummies. Sacred oaths were sworn on onions. The delicate, juicy plant was dedicated to the great goddess Isis, and it was forbidden for her priests to eat onions. Isis is the mistress of the periodicity of the moon and women’s rhythms. Egyptians believed that the growth of the onion was connected to the moon’s phases just as women’s menstruation is. The Egyptian hieroglyph for the moon in its waning and waxing form is an onion. The moon gives the plants their life energy and rules over life’s liquids. As the mistress of the moon, the goddess also rules over the waters, the cosmic milk of life. The onion absorbs this cosmic milk; when a person eats that onion, the glands are activated—including the reproductive glands. Thus, the onion also became a symbol of lust and procreation. The ancient Egyptian word for testicles—separate from the moon hieroglyph mentioned above—was the same as for onion. Indian Ayurveda also claims that onions nourish a man’s seed (shukra), for which reason doctors prescribe it to increase the amount of semen. Indeed, Indian penitents and ascetics (sannyasi) who have sworn off worldly matters and procreation avoid eating onions and garlic under any circumstances.

Classical antiquity and early Christianity saw another aspect of the onion’s various members of the lily family: they were seen as symbols of purity, innocence, and virginity. In Greece it was believed that lilies sprang out of the earth from milk that dripped from the breasts of cow-eyed Hera, the queen of heaven. For Christians the lily became a symbol of Virgin Mary’s immaculate conception: archangel Gabriel floated down from heaven with a white lily in his hand when he announced the conception to Mary. These beliefs are based on the perception that lily plants are not strongly bound to the earth; their roots are shallow, and the way the bulbs round out at the bottom resembles a drop of water. These bulbs symbolize the path taken by incarnating souls as they pass from high heaven, crossing over the gateway of the moon down to the material sphere of the earth. But also they symbolize the return from earth back to the eternal womb of being.

Kitchen onions and garlic don’t just belong to the watery moon and the gentle white goddess; they also contain the pungency of Mars, the god responsible for fiery drive. For this reason the Greeks believed onions stimulate sex drive and general vivaciousness. With the Romans it was no different—as this Roman saying regarding male impotence declares: “If onions cannot help, nothing will!”

In their conquest of northern lands Roman legionaries brought cultivated onion varieties that they planted in their gardens. The Celts and Germanics were enthused about this new “leek,” especially since bear’s garlic, also called “ramsons” or “wild garlic,” was already considered sacred by the northlanders, who regarded it as vitalizing, blood cleansing, and aphrodisiacal. This foreign “leek”—for which the barbarians used various names, such as ynnlek, allouk, oellig, ublek or ullig—found its way into each woman’s house garden, where it remained. German botanist Hieronymus Bock (1498-1554), who had heard about the Egyptians’ worship of the sacred onion, commented: “We Germans can also not do without such godly goods… . There are many who believe that if they eat some raw onion on an empty stomach the first thing in the morning they will be protected from bad, poisonous air for the entire day… . Many use it for lustful pleasure, and others use it medicinally.” Furthermore, he noted that in Germany hardly anything was used more for baking pies than onions. To this day in southern German regions onion pie is a specialty. Every year on the fourth Monday in November Berne, Switzerland, holds an onion market (Zibelemärit) where one can enjoy onion pie and onion soup and where over one hundred thousand kilos of skillfully wrought colorful onions braids are sold.

Of course onion soup is also a famous French specialty, which, according to Maurice Mességué, is actually for “longue nuits de folie (long nights of [sexual] foolishness).”

For the peasant culture of Europe the onion played an important role as a healing plant, a plant for the time of Lent, and a comestible good. It is no wonder, then, that an intricate lore developed around cultivating onions. Seed onions were put into the soil in the sign of Capricorn so that they would become firm and hard—whereas in Aquarius they would rot and in Sagittarius they would shoot up without making a bulb. When planting them in the soil it was recommended to do so angrily, swearing, which would make the onions fiery. It was also thought that onions planted on Good Friday, the day the Lord was nailed to the cross, would be pungent, making “lots of tears flow” when eaten.

European peasants used onions as an oracle during the twelve days of Christmas. A teacher of mine, the old Swiss peasant philosopher Arthur Hermes (1890-1986), would peel twelve onionskins and name them after the months. Then he’d sprinkle some salt on them; the next morning he’d assess how much moisture had accumulated on them overnight. In this way he forecasted how much precipitation there would be in the following year’s corresponding months. “The oracle is always right!” he claimed. This onion oracle is known all over Europe. Young women also used the onion as a marriage oracle. On Christmas Eve they would put one onion for each bachelor they knew in a corner of the warm living room. On Three King’s Day (January 6) they would see if any had sprouted. If none had sprouted there would be no wedding in the coming year.

At the more esoteric level, opinions differ regarding onions. Like the Indian sannyasins, some people avoid eating onions so as to not enmesh the spirit in sensuality. Others, such as the Dutch alternative healer Mellie Uyldert (1908-2009), see in the onion the power of spiritual sublimation. She believed the plant absorbs etheric life force of the soil, which it stores it in its shallow-rooted bulb; then, in the second year, the energy shoots upward into flower, leaving the skins lifeless hulls. To her, this signifies that onions enrich our lower chakras with life energy—the energy needed to pull the soul upward into the spiritual realm. Onions, in other words, refine and spiritualize the subtle energies: “Onions help us sublimate, give us the strength to ascend from matter to spirit—for that reason it makes good sense to eat onions for each meal” (Uyldert 1984, 102).

Garden Tips

Cultivation:

SET CULTURE: Sets are little pickling onions used to produce scallions (when young) or cooking onions (when picked later in the season). They are of the Ebenezer type, which are either yellow or white onions. Look for plump, medium-sized sets that have not yet sent out shoots, as they will provide the best onions. Plant the sets carefully, root end down, covering them with a half inch of soil. Give them ample moisture and keep them free from weeds. In five weeks or so you can pull some as scallions, leaving the remainder to harvest at the end of the season.

PLANT CULTURE: Plant onions are bought in bunches (usually 50 to 100 to a bunch). Red slicer onions of the Bermuda type are grown from plants, as are the large yellow and white sweet Spanish varieties. Like sets, they are planted early in the spring at their natural depth.

SEED CULTURE: Sow seeds thickly in rows in early spring and thin the young plants to stand two to three inches apart. They can be further thinned during the growing season and used as needed.

OF SPECIAL NOTE: Pinch off the flower buds as soon as they appear; this prevents the neck from becoming large and stunting the bulb. When the tops begin to wither and fall over, the onions are mature. Pull the onions a few days later, during a sunny period, leaving them on the ground for a day or two to cure naturally from the sun and wind. (LB)

SOIL: Onions need deeply prepared, fertile, loose soil.

Recipes

Spring Onion Soup with Thyme Bread ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1 pound (455 grams) spring onions (green onions), chopped ✵ 3 tablespoons olive oil, plus 2 tablespoons ✵ 1 tablespoon honey ✵ 1¼ cups (300 milliliters) white wine ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ ½ cup (115 milliliters) cream (18% fat) ✵ 1 teaspoon horseradish ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ black pepper ✵ 4 slices of bread ✵ some fresh thyme leaves ✵ 4 tablespoons Parmesan cheese, grated ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil

SOUP: Sauté the green onions in 3 tablespoons of the olive oil until brown. Stir in the honey, wine, and vegetable broth. Simmer for about 40 minutes. In a small bowl, mix the cream and horseradish. Transfer the soup to a serving bowl. Just before serving the soup, gently stir in the cream mixture.

THYME BREAD: Place the bread slices on a baking sheet. Arrange the thyme leaves on the bread. Sprinkle the Parmesan on the bread. Drizzle the remaining 2 tablespoons of olive oil on the bread. Broil the prepared bread in the oven until crisp, checking every few minutes, up to about 10 minutes. Serve with the soup.

Onion-Grape Soup with Roasted Feta Bread ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1 cup (225 grams) white or yellow onion, finely chopped ✵ 3 tablespoons fresh thyme leaves ✵ 2 tablespoons olive oil, plus 1 tablespoon ✵ 1 tablespoon honey ✵ ¾ cup (200 milliliters) white wine ✵ 1 quart (945 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ ½ cup (115 grams) grapes, both red and white ✵ 4 slices whole wheat bread ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ 3 ounces (85 grams) Feta cheese, sliced ½ inch thick

ONION-GRAPE SOUP: In a large pan, sauté the onions and thyme leaves in 2 tablespoons of the olive oil until browned. Add the honey. Add the wine. Let simmer for 5 minutes. Add the vegetable broth and simmer on low for 20 minutes. When ready to serve, transfer the soup to a serving bowl. Add the grapes just before serving.

FETA BREAD: Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Place the bread slices on a baking tray. Season the bread with herbal salt and pepper. Drizzle the remaining 1 tablespoon of olive oil on the bread. Place the Feta cheese slices on the bread. Bake at 350 °F (175 °C) until brown. Serve with the soup.