A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus, Hibiscus esculentus)

Family: Malvaceae: mallow family

Other Names: abelmosh, bamia, bhindi, bindi, gumbo, ladies’ fingers

Healing Properties:

TAKEN EXTERNALLY: the plant slime has a softening and soothing effect as a poultice for frostbite, lesions, and skin burns

TAKEN INTERNALLY: eases gastritis and hoarseness

Symbolic Meaning: male sexual energy, black “soul,” négritude, relaxed southern lifestyle

Planetary Affiliation: Mercury

The lush okra plant, which can grow up to six feet (nearly two meters) high, is an adornment for any vegetable garden. The beautiful blossoms, with their yellow petals and deep red pharynx that resemble the hibiscus, are excellent bee feeders. The plant constantly produces new pods—the so-called “ladies’ fingers”—until frosts come.

This member of the mallow family, a close relative of hibiscus and cotton, is a child of tropical Africa; wild forms of the plant are still found in Nubia, in the area of the White Nile. Anthropologists and paleobotanists have evidence that okra has been cultivated since Neolithic times in sub-Saharan Africa—as far back as six thousand years. Presumably the mild, slimy/gooey leaves and pods were eaten as vegetables; the stem fibers used to make rope, nets and carrying bags; the mucilage used medicinally; and the ripe seeds roasted as “coffee” or used to make cooking or lamp oil.

The mild-tasting vegetable is very healthy: it has a lot of calcium, provitamin A, vitamin C, and folic acid. The seeds are antioxidants—replete with unsaturated fats, such as linoleic acid—and they have as much protein as soybean seeds do. Today, okra seeds—which contain up to 25 percent fatty oil—are used in margarine production. Since okra is so slimy, it’s ideal for intestinal ailments.

Like the many plants described in this book, okra has made a long journey, which began when it traveled from Africa to India in Neolithic times. Even then, trade routes existed between pre-Aryan Harappan culture and eastern North Africa. Since that time one cannot imagine Indian cuisine without this delicate vegetable, which is mixed into various chutneys and used to thicken soups or bind sauces.

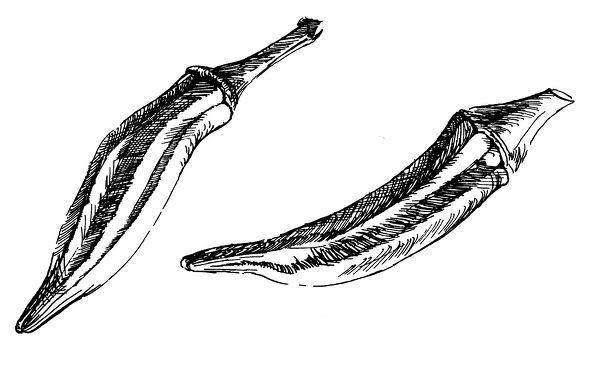

Illustration 51. Okra pods

In another phase of okra’s journey, the ancient Egyptians learned about it from Nubian Africans. Not long after, the plant conquered Arabic gardens and kitchens, where it is called “bamia.” Okra is highly valued there because its seeds smell like musk, the erotic perfume from the sex glands of musk stags.1 (Okra is a close relative of the “abelmosk” [habb-al-misk], the “son of musk,” as they share the genus [Abelmoschus].) Musk is the favorite perfume of the Islamic countries: it is the scent of seventh heaven. The Houris, the doe-eyed ladies of pleasure in paradise, supposedly wear scarves scented with musk fragrance. Musk has long been mixed with the mortar used for building mosques; even centuries later, the otherworldly scent within the walls still beguiles those who pray there. Arabs and Turks mix crushed okra seeds into coffee and cooling fruit drinks (sorbet); the seeds are sprinkled into clothes and chewed to improve the breath.

From Africa, okra headed west as well as east. Arabian conquerors brought musk to Spain and western Europe; by 1600 the vegetable was introduced to Brazilian cooking. Black slaves brought with them on their reluctant, harrowing journey to the New World—along with other cultural elements, such as mojo magic, certain dance and drum rhythms, tales, certain speech rhythms and intonations, ecstatic religious cults, voodoo—specific ways of cooking and seasoning, as well as many aspects of African healing, in addition to the seeds of their favorite plants,2 including what West Africans called “okra” and the Bantus called “gombo bambia” or “guimgumbó.” From this came the word “gumbo”; indeed, in former times blacks were also called “gumbo” in the southern states, especially those who escaped. Even today, both okra the plant and gumbo the okra stew are soul food for American blacks. Fried chicken and catfish, collard greens, pork belly, testicles, tripe, and other innards (chitterlings or chitlins) were—and to a degree still are—all part of soul food, seasoned in a more or less west-African style. In Louisiana, the dried and powdered okra leaves used to thicken soups and stews are called “gumbo filé.” African Americans in the southern states dried the leaves and the halved fruits for winter, and roasted the seeds to brew a sort of coffee.

African Americans also preserved their ancestors’ practices using okra for healing. Poultices made of the leaves ease pain and soften tissue: the plant’s mucous compounds serve as an emollient that, used topically, soothes infected tissue and softens scarred and hardened tissue. Ingested okra is both anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcerogenic, and aids treatment of digestive diseases and lung ailments. According to Indian as well as African lore, the hibiscus family makes genital organs more mucilaginous. Okra and other kinds of hibiscus are therefore used as a strengthening agent. It is said that Hibiscus mochatus will restore the manly strength of even an eighty-year-old man. Historian George Bancroft (1800-1891) reported that southern slave women observed an okra diet before having an abortion to make the uterus slithery and soft.

I got to know okra through a friend of mine, an old Texan who loved the plant and generously shared its seeds. But though he grew it with great success, not every gardener will fare as well with the plant; perhaps one needs a certain Southern magic to do so. As far as the African soul of the plant goes, a jazz musician friend from New Orleans—who conjured the coolest, most bizarre riffs on a clarinet I’ve ever heard—confided to me that his secret was eating several portions of okra every day. He felt the slimy vegetable brought him “into the groove,” that it smoothed the sound he played and protected his lungs in smoky nightclubs. Just like his favorite dish, his music, jazz, also has African roots. “Jizz,” or “jizzm” (possibly the word from which jazz is derived), is a vulgar expression for both semen, life-carrying slime, as well as for the smooth rhythmical movement of the act that makes life possible. Jazz is, then, sex as sound.

The association of okra to sexuality can also be found in India, where the god Ganesh is worshipped with hibiscus or okra blossoms. Ganesh, the elephant-headed god who loves to dance, dwells mainly in the root chakra (Muladhara); his trunk symbolizes the penis.

The sensual imagery associated with okra might not please everybody; it certainly would not have pleased my rather puritanical neighbors in the small Ohio town where I grew up. That should not, however, stop them from enjoying a meal of this delicious, nutritious vegetable.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION AND SOIL: Okra can be easily cultivated in areas where vineyards thrive and tomatoes, cucumbers, and melons grow well. After two months the tender, unripe pods can be harvested for use as a vegetable; cut crosswise, the pods have a pentagonal shape. After another two months the plant will produce ripe seeds; a smart gardener will grow the seedlings in a green house or in a nursery in peat pots before planting them out into the garden. Okra needs a good spell of summer heat, rich, well-draining soil, and plenty of water. It is a rapid-growing, heavy feeder that should be planted in a fully sunny location that has been well composted and well manured.

Sow seeds lightly in rows or in hills after all danger of frost is past and when the soil is warm. Note that, as the seeds rot easily, a rainy period just after planting could cause the seeds to rot, in which case replanting may be necessary. Once the plants are a few inches tall, thin them to stand twelve to sixteen inches apart. (LB)

Recipes

Okra Stew with Garlic ✵ 4 SERVINGS

4 potatoes, peeled or unpeeled, cubed ✵ 4 garlic cloves, peeled ✵ 4 tablespoons olive oil ✵ 1 pinch of cinnamon ✵ sea salt ✵ black pepper ✵ 1 pound okra

In a medium pan, sauté the potatoes and garlic in 2 tablespoons of the olive oil for 20 minutes. Season with the cinnamon, salt, and pepper to taste. In a separate large skillet, sear the okra in the remaining 2 tablespoons of olive oil for 3 to 4 minutes or until tender. Add the potatoes and garlic to the skillet. Mix well and serve hot.

Okra with Coconut ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1¾ pounds (800 grams) okra, chopped ✵ 3 ounces (85 grams) coconut flakes ✵ 3 tablespoons ground coriander ✵ 1 tablespoon turmeric powder ✵ 1 pinch cayenne ✵ 5 tablespoons butter ✵ 2 teaspoons caraway seeds ✵ 2 teaspoons black mustard seeds ✵ salt ✵ 1 teaspoon sugar ✵ lemon juice ✵ 6 ounces (175 milliliters) coconut milk

In a large bowl, mix the okra with the coconut flakes, coriander, turmeric, and red pepper and let rest for about 10 minutes. In a big frying pan, melt the butter and sauté the caraway seeds and mustard seeds until brown. Add the okra and coconut to the pan and sear for 5 minutes. Add the lemon juice and coconut milk and simmer for about 20 minutes or until okra is tender. Serve immediately.

TIP: Use a big frying pan for searing the okra; otherwise it will get too slimy and juicy.