A Curious History of Vegetables: Aphrodisiacal and Healing Properties, Folk Tales, Garden Tips, and Recipes - Wolf D. Storl (2016)

Common Vegetables

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

Family: Compositae: composite, daisy, or sunflower family

Other Names: Canada or French potato, earth apple, girasole, pig’s potatoes, sunchoke, tuberous sunflower, topinambour

Healing Properties: curbs the appetite, improves intestinal flora; ideal for diabetes diet

Symbolic Meaning: the sun god Helios imparts the strength of the higher self; exoticism, luxury; but also hunger and need

Planetary Affiliation: Sun

Many today have no idea what a Jerusalem artichoke, or sunchoke, is, especially as the information about it found in cookbooks or garden literature is often both minimal and incorrect. Occasionally one may find the reddish purple, beige, or pale brown tubers in stores—alongside exotic vegetables such as ginger, Inca berries, mangos, and okra—and some gourmands are willing to pay a pretty penny for them. Sometimes they’re assumed to be sweet potatoes, although the latter belongs to the morning glory family.1 (In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, merchants and common people alike were confused about the various exotic tubers from the New World.) For the French or Germans, who call it tobinambour, Jerusalem artichokes conjure up images of the jungle and the Amazon.

The root tuber is tasty when prepared correctly. Sliced raw into salads, seasoned with oil and lemon, it’s similar to the refreshing, crunchy Chinese water chestnut.2 When roasted, steamed, or boiled it has a slightly sweet flavor, somewhere between artichoke hearts and salsify. It’s a delicacy when pickled like cucumbers. For the Europeans who survived the Second World War, however, the Jerusalem artichoke is considered anything but exotic; for them the mild, sweetish vegetable awakens memories of hardship, deprivation, and hunger. This was because it was grown everywhere in Europe at the time, and for good reason: the plant produces three to four times as much edible bulk as would potatoes on the same amount of land, it requires minimal tending, and it doesn’t leech the soil. After the economic boom in the 1960s the tuber mostly sank into oblivion. Hunters planted it to feed the deer and other wild animals in the European forests. Only anthroposophists remained faithful to the plant. They saw it as an “astrally sunny” alternative to the—in their opinion—more dubious, dark, “materialistic and Ahrimanic” potato of the nightshade family.

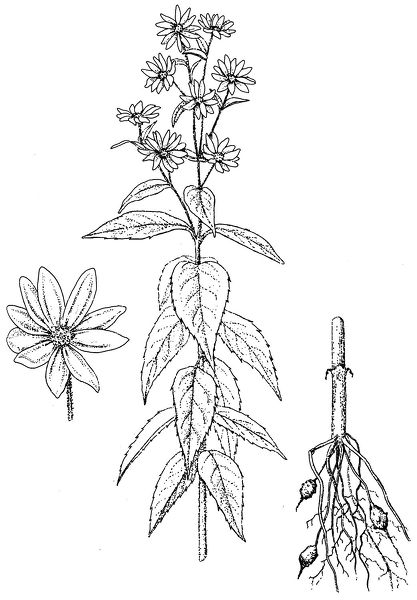

Illustration 42. Jerusalem artichoke: leaves and roots

The Jerusalem artichoke is actually a kind of sunflower with storage roots and flowers that are three to five inches in diameter. Like its sister, the much larger common sunflower (H. annuus), its blossoms rotate in following the sun’s daily movement across the sky. A native of the North America prairie, it grows from Saskatchewan to the Mississippi Delta. Jerusalem artichokes and other kinds of sunflowers grew in the endless expanse of six-foot-high prairie grass that once fed the huge population of freely roaming bison. The sunchokes lifted their yellow floral disks above the waving ocean of grass much like dandelions or daisies do in our mowed lawns. But the Jerusalem artichoke differs from its annual sunflower cousins in that it keeps its life force concentrated in its tuber rather than expending its energy on a huge blossom with many heavy, oil-bearing seeds before dying off. As a short-day plant, the sunchoke blossoms only after the fall equinox, when the days become noticeably shorter than the nights. In Canada and Norway the plant is often surprised by the sudden onset of winter and cannot even make seeds—thus highlighting the value of its storage roots energy source. Not only does the plant send out vital offshoots in all directions, which take on mass as they expand, but the tubers are also carried off and widely distributed by rats, prairie dogs, gophers, and voles. Each small piece that rodents drop sprouts and becomes a new plant.

The Prairie Indians considered Jerusalem artichoke—“pangi” or “panhi,” as they called it—an important edible plant. In the dearth of springtime, when winter provisions were running out, the freshly dug tubers made survival possible. All the same, some of the Native Americans didn’t value the plant as much. For the Omahas it was “nourishment for orphaned boys who have no relatives to feed them.” The Sioux did not like it because it causes flatulence—which complicates life inside a tepee. (In Europe the cooked tubers are often seasoned with caraway, which counters their flatulent effect.)

The Huron and other eastern forest tribes both gathered the tubers and cultivated them in round raised beds. Samuel de Champlain (1574-1635), the founding father of French Canada, discovered the plant—the “sun root” to the Algonquian—in Native American gardens near Cape Cod. When he later brought some back to France, these “Canadian potatoes (batatas de Canada)”—“as thick as a fist, with an artichoke taste and incredibly fertile” (Histoire de la Nouvelle France, 1609)—became a sensation in the French court, a delicacy in high demand.

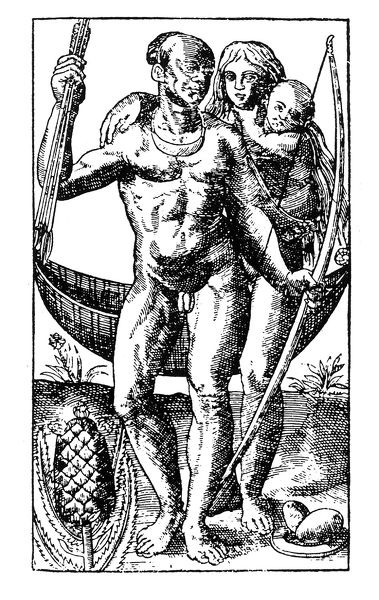

A side story explains how the plant got its modern exotic name. Around the same time (1613), a French nobleman returning from Brazil brought with him some Indians from the tribe of the “Tupinambous” as a living present to his queen. The abducted Amerindians—already known to the French—belonged to a larger ethnic group, Tupí-Guaraní, that lived near the Amazon region in palisaded villages. They were previously known in Europe because the Hessian adventurer Hans Staden (1525-1576), who’d been captured by this warrior-like tribe, wrote a book about his adventures, True Story and Description of a Country of Wild, Naked, Grim, Man-Eating People in the New World, America (1557).3 In addition, French seafarers had traded with them, winning them as allies against the Portuguese. And now these native people, celebrated as “Allies of La Grande Nation,” stood in the flesh for everyone to gawk at and paw over—after having first been baptized and anatomically examined by scientists before being passed around, not least of all for erotic amusement, in French society. As such, the “Tupinambá” were a grand sensation. Their name became a fashionable word for everything that was exotic, strange, and fantastic. And so, the new tuber was sold as “the vegetable of the marvelous Topinambous,” despite the sheer lack of connection these South American Natives had with the North American prairie plant. All the same, it soon joined Parisian haute cuisine under the name “topinambur.”

Illustration 43. South American Tupí-Guarani Indians, “exhibited” in France in 1619; the tuber is named after them (from Le Voyage au Brésil de Jean de Léry, 1556-1558)

Soon thereafter the “Canadian potato” also became known in England. Botanist John Parkinson (1567-1650) described it as “a delicacy fit for a queen.” Benjamin Townsend, gardener of a British lord, wrote in his 1726 The Complete Seedsman, “The cooked tuber is most appropriate for Christmas dinner.” Given the vegetable’s burgeoning popularity, it inspired many venturesome recipes. The tuber was baked, peeled, and sautéed in butter, wine, and expensive spices; or it was baked with bone marrow, dates, ginger, and raisins in a sherry sauce. It was also cooked in milk and served with roast beef.

The Italians also made friends with the “sunflower that tastes like artichoke.” It was first cultivated in the famous Farnese Gardens near Rome, and known as girasole articiocco. (English gardeners later distorted the name into “Jerusalem artichoke.”) But the simple folk didn’t glorify the vegetable as others had done, and considered these tubers much as they did potatoes. They were both grown in the ground and were both called “earth apples”—pommes de terre. Like ordinary potatoes, they were also often distilled to make homemade liquor.

But the Jerusalem artichoke’s popularity wasn’t to last. For one thing, it grows prolifically—once planted it can hardly be removed. This makes it a poor candidate for the age-old practice of rotating crops and leaving fallow fields. Instead, the summer crops of broad beans, millet, and lentils were cultivated instead. Then, in the nineteenth century, with the development of modern agriculture, those time-worn crop-rotation practices were abandoned as well, and potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) were planted in every field. Soon boiled potatoes and fried potatoes became the mainstay of both industrial workers and the soldiers of modern draft armies. Already pushed out of the field, and difficult to harvest with machines, the Jerusalem artichoke could not compete with the ordinary spud. With the increasing mechanization of agriculture the sunchoke sank slowly into near oblivion, serving only as emergency food in times of hunger and as fodder for hogs. Indeed, they proved very useful with pigs, who in grubbing them out of the ground with their snouts simultaneously ploughed and manured the soil. And so the once-proud vegetable of lordly banquets became “pig’s bread” or “pig’s potatoes.”

Fortunately for us, modern organic gardeners and nutritional researchers have rediscovered the Jerusalem artichoke. More popularly called “sunchokes,” they are praised as highly nutritional and healthful. They have far more mineral nutrients than potatoes, more blood-building iron than spinach, and six times more potassium as bananas. (Potassium has a strong flushing, cleansing effect.) Sunchokes are very rich in calcium carbonates and silica, good for teeth and bones, as well as vitamins and protein. They’re also a good source of fructooligosaccharides (FOS), which trigger an increase of bifid bacteria in the lower intestines—thus contributing to intestinal health and, by extension, the immune system.

They are also regarded as appetite suppressants. The tuber does not contain starch, but inulin; in the liver the inulin gets converted into glycogen, a polysaccharide that stabilizes blood sugar levels and, by extension, reduces hunger. It’s no wonder, then, that so many Jerusalem artichoke products—juice, pills and supplements—abound in the health food stores. In addition, sunchokes’ fructose compound inulin makes it a delicate potato for diabetics. As inulin stimulates insulin production in the pancreas, it’s ideal for early stages of diabetes and adult-onset diabetes. In fact, in as early as 1878 the “sleeping prophet,” Edgar Cayce (1877-1945), brought out of the spiritual realm a message declaring that the Jerusalem artichoke was capable of waking “God’s forces” in diabetics. (Cayce was an interesting character; while in a trance he was able to diagnose and prescribe cures and medication—considered accurate today—knowledge he did not possess in his waking consciousness.)

Anthroposophical medicine also recognizes Jerusalem artichoke for healing diabetes. According to Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), sugar is mineralized sunlight. If the “Self”—our spiritual essence—is not strong enough to support the processes of sugar digestion in the organism, then help from nature becomes necessary. That is when this sunny tuber comes into consideration. In imparting (or conveying) macrocosmic sun/sugar power, the sunchoke helps the internal “true being,” the “spiritual sun,” bring order into one’s metabolism.

Garden Tips

CULTIVATION: This tuber is best planted in a sunny, sectioned-off spot; since they spread out very fast, they can easily overtake a garden if left to do so. They should be planted much like potatoes in rows or hills, set about a foot apart. Plant either a whole tuber or a tuber cut into pieces with at least one eye per piece. Planting should be done around the same time as potatoes. Harvest the tubers after the first frost in the fall and continue to harvest as needed until the ground becomes too frozen; they will survive the winter and continue to grow in the spring. They can be stored as one would potatoes. Another benefit: because the plant grows so tall (up to six feet), it makes an attractive screen against prying eyes. (LB)

SOIL: Jerusalem artichokes/sunchokes grow in any soil except heavy clay. Contrary to most vegetables, the plant even prospers in poor soil. Too much nitrogen forces greater top growth and the tubers remain small.

Recipes

Sunchoke Soup with Nutmeg ✵ 4 SERVINGS

1 pound (455 grams) sunchokes or potatoes, peeled or unpeeled, finely chopped ✵ 3 ounces (85 grams) leeks, cubed ✵ 2 ounces (60 grams) pumpkin, cubed ✵ 1½ quarts (1½ liters) vegetable broth ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ 1 ounce (30 grams) brown lentils, ground ✵ herbal salt ✵ pepper ✵ 2 ounces (60 grams) cream cheese ✵ 1 tablespoon hazelnut oil ✵ chervil, finely chopped

In a large pot boil sunchokes (or potatoes), leeks, and pumpkin in the vegetable broth until tender. Season with nutmeg to taste. Stir in the ground lentils. Bring the soup to a boil again. Season with herbal salt and pepper to taste. Add the cream cheese. Transfer the soup to individual bowls. Garnish each with a few drops of hazelnut oil and a pinch of chervil.

Sunchoke Gratin with Plums ✵ 4 SERVINGS

Butter for greasing ✵ ground nutmeg ✵ cinnamon ✵ 1 pound (455 grams) sunchokes, sliced ½ inch thick ✵ 2 pitted, tart plums (~100 grams), halved ✵ ¾ cup (175 milliliters) vegetable broth ✵ ¾ cup (175 milliliters) cream (18% fat) ✵ 2 eggs, whisked ✵ 1½ ounces (40 grams) ground hazelnuts ✵ 3 ounces (85 grams) cheddar cheese, grated ✵ herbal salt

Preheat the oven to 350 °F (175 °C). Butter the casserole dish; sprinkle with nutmeg and cinnamon. Put a layer of sunchokes in the dish. Add the plums in a layer. Top with the remaining sunchokes. In a separate bowl, combine vegetable broth, cream, and eggs; season with herbal salt. Pour the mixture over the sunchokes and plums. Sprinkle the hazelnuts and cheese on top. Bake at 350 °F (175 °C) for 1 hour or until firm and golden.

TIP: This dish pairs nicely with a delicate salad.