Wild Spring Plant Foods: The Foxfire AMericana Library - Foxfire Students (2011)

SPRING WILD PLANT FOODS

The forests and fields of the mountains are literally filled with edible leaves, berries, and roots. Many of these have been used by the mountain people for several generations. In pioneer days, the use of wild plants to supplement the daily diet was a necessity, and many of the plants used served as tonics or medicines as well. Nowadays, with the lure of modern food markets, the use of many of the wild plants is a matter of choice, rather than need. Many of our informants say, “My mother, or my aunt, or my grandmother used that but we don’t bother gathering it.”

There is a revival of interest in the wild plant foods, for many who have migrated to the city are finding pleasure and good eating in returning to the country on occasion and gathering wild greens or berries. Most of the wild plants have a high vitamin and mineral content, and add greatly to the foods essential for good nutrition.

We began gathering information on this topic several years ago. Though it is not a complete handbook or guide to the woods by any means, it does reflect everything we have found so far; and everything included here has been verified and rechecked with our native informants (with the exception of those few recipes marked by an asterisk, which are recipes that came to us second-hand rather than directly from our mountain contacts).

In addition, we have enlisted for this chapter the invaluable aid of Marie Mellinger, a local botanist, who checked all our plant specimens, verified their botanical names and characteristics, tried almost every one of the recipes herself, and helped us compile all this into a chapter that would make some sense and that you might use yourselves. With her help, we’ve listed the plants according to their botanical order. Mrs. Mellinger also found Carol Ruckdeschel for us, a botanical illustrator, who provided us with the pen-and-ink drawings.

For those of you who intend to try to find and use some of these plants yourselves, we should emphasize that the plants named are those traditionally used here in southern Appalachia. Although they may well exist in your part of the country, you may need to consult a local plant guide to make sure. And we would also urge you to avoid plants that are becoming rare and on the verge of extinction in your areas. There will be no problem with the vast majority of these—dandelion, for example—but in this age of asphalt and summer home developments, edible plants such as Indian cucumber, wild ginger, and wintergreen have suffered terribly.

And we must issue a word of caution. John Evelyn wrote, “How cautious then ought sallet gatherers be, lest they gather leaves of any plant that do them ill.” NEVER GATHER A PLANT UNLESS YOU ARE FAMILIAR WITH IT! Some plants are safe to use in small quantities, for example, sheep sorrel (Rumex) and wood sorrel (Oxalis), both rich in vitamin C. Overuse should be avoided because of their high content of oxalic acid. Sometimes one part of a plant will be safe to use, such as the stems of rhubarb, while the leaves must be avoided. Some plants are safe only after cooking.

One mountain man told us that people used to follow the cows in the spring of the year, to see what they would eat. This could be dangerous, for cows are notoriously stupid, and will eat the plants that cause milk-sickness, and such deadly things as wiited cherry leaves.

Most greens and salad plants used are in the mustard family and composite family. Most of the plants of the mustard family used for greens have a most characteristic mustardy smell and sharp pungent taste. Most fruits and berries are in the rose or heath family. Plants to be avoided are those of the parsnip family, for many resemble the deadly cow parsnip, or water hemlock. Someone, sometime, must have experimented, finding the edible plants by trial and possibly fatal error. Now there is no necessity for that. Descriptions, drawings, and photographs of the edible plants all help you to determine their identity.

There is almost nothing better after a long winter (and remember, most greens are best when young and tender) than a mess of dandelion, lamb’s quarters, or cress. Absolutely nothing equals a dish of wild strawberries freshly gathered in a sunny meadow, with all the goodness of sun and rain within their tart sweetness. Have fun in the gathering, and good eating!

SPRING TONIC TIME

After a long winter, spring was the time to refresh the spirit and tone up the system with a tonic. The mountain people used teas as beverages and as tonics. They would gather the roots or barks in the proper season, dry them, store them in a dry place, and use them as they wanted them. People used sugar, honey, or syrup to sweeten the teas. Common spring tonics were sassafras, spicebush, and sweet birch.

Lovey Kelso told us, “We had to have sassafras tea, or spicewood, to tone up the blood in spring, but I never cared for either.”

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) (family Lauraceae)

(white sassafras, root beer tree, ague tree, saloop)

Sassafras is usually a small tree, growing in clumps, in old fields and at woods’ edge. It is one of the first trees to appear on cut-over lands. In the mountains, however, sassafras may grow to sixty feet tall. Twigs and the bark of young trees are bright green, older bark becomes crackled in appearance. Leaves are variable in shape, being oval, mitten-shaped, or three-divided. Leaves, twigs, and bark are all aromatic. The greenish-yellow, fragrant flowers appear in early spring and are followed by deep blue berries. The so-called “red sassafras” is identified by some botanists as Sassafras albidum variety molle, and has soft hairiness on the leaves and twigs. The recipes that follow can be used with either variety.

ILLUSTRATION 1 Sassafras in spring

Twigs, roots, or root bark are used for tea, candy, jelly, and flavorings. Leaves are dried and used to thicken soups. Blossoms are also boiled for tea.

Sassafras has a long history of use as food. It was one of the first woods exported to England where it was sold as a panacea for all ills, guaranteed to cure “quotidian and tertian agues, and lung fevers, to cause good appetite, make sweet a stinking breath, help dropsy, comfort the liver and feeble stomach, good for stomach ulcers, skin troubles, sore eyes, catarrh, dysentery, and gout.” There was even a song used to advertise sassafras: “In the spring of the year when the blood is too thick, there is nothing so fine as a sassafras stick. It tones up the liver and strengthens the heart, and to the whole system new life doth impart.”

In the mountains sassafras has always been used as a beverage and a tonic. There is an old saying: “Drink sassafras during the month of March, and you won’t need a doctor all year.” Sassafras was a blood purifier and tonic and a “sweater-outer” of fevers. Red sassafras is best, but as someone said, “Red is hard to get nowadays. The mountains used to be full of it.”

Sassafras is best gathered in the spring when the bark “slips” or peels off easily. Florence Brooks told us, “Find a small bush, pull up roots and all, or dig down by the base of a tree and cut off a few sections of root. Wash the roots and scrub until the bark is pink and clean. Peel off the pinkish bark for tea.” Mrs. Norton said that “some claim the root is better but you can just use the branches.” Big roots should be “pounded to a pulp.”

Fanny Lamb said, “Get some sassafras when the leaves are young and tender, just eat leaves and all like you have seen the cows do. Eat leaves and tender twigs and everything.”

Alvin Lee wrote, “It’s a remedy for colds, and for those down in the dumps from a long winter. It’s a spring tonic. ’Course some folks drink it year around.” Sassafras is supposed to be used on and after February 14. With golden seal and wild cherry, it makes a very potent tonic.

Sassafras tea: gather old field roots and tender limbs in March. Boil roots and limbs and sweeten with sugar to taste. Or wash roots, beat to a pulp with a hammer. Boil, strain, sweeten, and drink with ice. Or put one cup shredded bark in quart of boiling water. Boil ten to twelve minutes, strain, sweeten with honey or sugar. Or use one five-inch piece of sassafras root one inch thick. Shave into two quarts water; boil, adding sugar or honey. “Mighty tasty if stirred with a spicewood stick.”

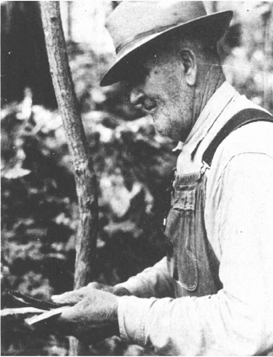

ILLUSTRATION 2 Harley Carpenter with strips of sassafras bark for tea.

Sassafras candy: grate bark, boil, strain, and pour into boiling sugar; then let harden and break into small pieces.

Sassafras jelly: boil two cups strong sassafras tea and one package powdered pectin. Add three cups strained honey. Strain and put in jars. Jelly will thicken slowly.

The leaves of red sassafras make a good addition to candy and icings. Add one teaspoonful of dried and pulverized leaves to a kettle of soup, or add one teaspoon of leaves to a warmed-up stew.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) (family Lauraceae)

(spicewood, feverbush, wild allspice, benjamin bush)

ILLUSTRATION 3 Spicebush

Spicebush is a shrub growing six to sixteen feet high in rich woods, ravine-covered forests, or on damp stream-sides. It has smooth green stems and twigs, with a strong camphor-like smell. The leaves are medium green, paler below, and fall early in autumn. Honey-yellow flowers appear before the leaves in very early spring. In fall, the bush bears bright red, or (rarely) yellow, aromatic berries.

Twigs and bark are used for tea. Berries can be used as a spice in cooking. Spicebush is gathered in March when the bark slips. Mrs. Norton told us, “You’ve heard tell of spicewood, haven’t you? Well, it grows on the branches [streams] and you get it, wash it, and break it up in little pieces. It tastes better than sassafras; it ain’t so strong.”

Spicewood tea: “Get the twigs in spring and break ’em up and boil ’em and sweeten. A lot of people like that with cracklin’ bread” (Mrs. Hershel Keener). Or gather a bundle of spicewood twigs. Cover with water in boiler. Boil fifteen to twenty minutes (or until water has become colored). Strain, sweeten with honey, if desired, or add milk and sugar after boiling. Especially good with fresh pork.

Spicewood seasoning: gather spicewood berries; dry and put in peppermill for seasoning.

Sweet Birch (Betula lenta) (family Corylaceae)

(black birch, cherry birch)

ILLUSTRATION 4 Sweet birch

The sweet birch is a common tree in the deciduous forests of the mountains, growing to ninety feet in rich ravines, along with tulip poplar and red maple. Bark on young trees is a red-brown, but becomes very crackled on old trees. The slender twigs smell like wintergreen. Catkins appear before the leaves in very early spring. Leaves are oval, tooth-edged, and deep green in color. Small seeds are eaten by many species of birds.

Buds and twigs are favored “nibblers” for hikers in the mountains, and will allay thirst. Twigs and root bark are used for tea, and trees are tapped so sap can be used for sugar or birch beer. At one time, the sweet birch provided oil for much of the wintergreen flavoring used for candy, gum, and medicine. The inner bark is an emergency food if you are lost in the woods, for it is rich in starch and sugar.

Sweet birch bark tastes quite good, and may easily be peeled off to chew like chewing gum.

Sweet birch tea: cover a handful of young twigs with water; boil and strain. Sweeten with sugar or honey. The birch is naturally sweet so needs very little extra sweetening. Good hot or cold. Or bore a hole half-inch thick into tree. Insert a topper or hollow toke of bark; hang a bucket under end of toke to collect sap. Drink plain, hot or cold.

Birch beer: Tap trees when sap is rising. Jug sap and throw in a handful of shelled corn. Nature finishes the job.

Morel (Morchella esculenta, M. crassipes, M. angusticeps)

(sponge mushroom, markel, merkel)

ILLUSTRATION 5 Morel

The mushroom most commonly gathered in spring, and a delight to eat, is the morel, Morchella. There are various signs to tell it is time to go morel hunting, but usually you look for them after a warm rain, when the dark blue violets bloom. A favorite place is under old apple trees.

All are wrinkled and pitted, and a light oak-leaf brown color. Avoid mushrooms having folds instead of pits. True morels are hollow. Morchella esculenta is found under old apple or pear trees when oak leaves are mouse-ear size. Look for the fat morel, M. angusticeps, in oak, beech, or maple forests when the service berry (Amelanchier) is in bloom. M. crassipes is found in swampy ground, almost always with jewelweed (Impatiens).These mushrooms are especially favored by people of Pennsylvania Dutch descent. They consider them the best of all edible mushrooms and use them in sauces, gravies, and soups. Morels can be dried for winter use. Hang them strung on twine, with a knot between each mushroom to keep them from touching. Hang in a dry place. Before using dried morels, soak in milk to restore freshness, or grind into mushroom powder.

Fried morels: soak in salt water. Slice crossways in rings. Dip in egg and corn meal, and fry at medium low heat. Or put one pint of morels in pan with egg-sized piece of butter. Sprinkle on salt and pepper. When butter is almost absorbed, add fresh butter and enough flour to thicken. Serve on toast or cornbread.

Stuffed morels: soak one-half hour in salt water; parboil lightly. Stuff with finely chopped chicken or cracker crumbs and butter or margarine. Bake at low heat for twenty minutes.

Merkel omelet: let stand in salt water one hour. Chop fine; mix with eggs, salt and pepper, and fry in butter.

Merkel pie: cut in small pieces. Cover bottom of pie dish with thin bits of bacon. Add layer of merkels, salt and pepper; then layer of mashed potatoes. Put in layers of merkels and potatoes, finishing with potatoes on top. Bake one-half hour.