Why Aren't We Saving the Planet?: A Psychologist's Perspective - Geoffrey Beattie (2010)

Part I. Notes on attitude

Chapter 3. Measuring attitudes to sustainability: easily, consciously and wrongly?

Allport made genuine advances in many areas of psychology. In order to develop his science of personality, He began by going through the dictionary and identifying every single lexical item that could be used to describe a person. His trawl pulled in 4500 trait-like words. In these lexical descriptors, the words used in everyday life, he saw the start of a new scientific theory of personality, rooted in the stuff of everyday life, in the words that we use consciously and deliberately to describe other people. It was four years later, in 1924 at Harvard, that Allport began what was in all likelihood the very first course on personality in the United States - ‘Personality: Its Psychological and Social Aspect’. It was the kind of course that could well fit into the modern psychology curriculum. He went on to develop theories and write books on prejudice, the psychology of rumour and the concept of the self, developing the careers of many outstanding social psychologists including Jerome Bruner, Stanley Milgram, Leo Postman, Thomas Pettigrew and M. Brewster Smith. Another of his students was Anthony Greenwald, whom we shall be encountering in a subsequent chapter. Given Allport’s stance on Freud’s fixed attentional gaze on the unconscious, it is highly ironic that Greenwald is best known for taking one of Allport’s core concepts, the attitude, and detailing the unconscious or implicit aspects of it; indeed, he challenged the whole basis for identifying and measuring it, but more of this later.

Allport himself viewed the concept of the attitude as the central plank of the new psychology. He defined it as ‘a mental and neural state of readiness organised through experience, exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related’ (1935:810). In other words, an attitude is an internal state of mind affected by what we do which affects our behaviour towards the world around us. In 1935 Allport announced proudly that this concept of the attitude was social psychology’s ‘most distinctive and indispensable concept’ (1935:798). Its importance should be clear - it should have a major impact on our behaviour (but of course it’s not the only factor and, in 1991, Azjen argued that the subjective norm, or how you think others will behave, and the level of perceived behavioural control, in other words the control you have over the particular behaviour, are also crucial).

Of course, there is nothing in Allport’s formal definition that formally excludes a possible unconscious component to the attitude (see also Greenwald and Banaji 1995:7). Indeed, Doob, another great scholar of attitude, working in the years shortly after Allport, had defined an attitude as ‘An implicit, drive-producing response considered socially significant in the individual’s society’ (1947:136) and in 1992 in an article in which he looked back at the early development of social psychology, he wrote that in the 1940s and earlier the notion of attitudes operating unconsciously was quite acceptable to many researchers.

But when you read this early work of Allport with fresh eyes, I think that you could go much further than this. I think that in Allport’s classic (1935) chapter, and despite what happened to him in Freud’s office, he initially displays considerable awareness of the unconscious dimensions of an attitude and great sensitivity to this unconscious aspect. When he talks about the early German experimentalists from the Würzburg school, he points out that they believed that attitudes were

neither sensation, nor imagery, nor affection, nor any combination of these states. Time and again they were studied by the method of introspection, always with meagre results. Often an attitude seemed to have no representation in consciousness other than a vague sense of need, or some indefinite or unanalyzable feeling of doubt, assent, conviction, effort, or familiarity. (Allport 1935:800)

Some psychologists (like Clarke 1911) clearly thought that attitudes were represented in consciousness through ‘imagery, sensation and affection’, but Allport himself seemed to hold quite a different view. Thus he wrote that

The meagreness with which attitudes are represented in consciousness resulted in a tendency to regard them as manifestations of brain activity or of the unconscious mind. The persistence of attitudes which are totally unconscious was demonstrated by Müller and Pilzecker (1900), who called the phenomenon ‘perseveration’. (Allport 1935:801)

So in this classic chapter, Allport not only displays explicit recognition of the significance of the unconscious dimensions of an attitude; he also praises Freud’s contribution to this concept, and specifically applauds him for endowing attitudes with ‘vitality, identifying them with longing, hatred and love, with passion and prejudice, in short, with the onrushing stream of unconscious life’ (Allport 1935:801). This all came from a man who had been personally put off by Freud’s attempt to psychoanalyse him in his office some fifteen years previously.

But his chapter has a historical time line underpinning it: as we get towards the middle and end of the chapter the unconscious is mentioned less and less, and by the final section the focus has moved entirely from the unconscious to the conscious - in effect, to what can be measured with the greatest ease. He seems impressed by Likert’s research which looked at white people’s attitudes to ‘Negros’ and the fact that scales could be used to determine ‘the amount of favor or disfavor toward the rights of the Negro’. The ‘Likert scales’ were measurement devices that pick up on conscious thoughts: sometimes thoughts that maybe we are not that happy with, but conscious thoughts nonetheless. Allport seems in awe of the work that had been done on intelligence testing, despite the fact that there was still huge disagreement about what ‘intelligence’ actually was. He wrote admiringly about the domain of intelligence, ‘where practicable tests are an established fact although the nature of intelligence is still in dispute’ (and, of course, he is alluding here to the huge debate then raging about how to define the concept of ‘attitude’).

These intelligence tests yielded vast amounts of quantitative data which in his view were clearly of practical value to an emergent nation. He saw the same practical application for attitude measurement and he concluded with some pride that ‘The success achieved in the past ten years in the field of the measurement of attitudes may be regarded as one of the major accomplishments of social psychology in America. The rate of progress is so great that further achievements in the near future are inevitable’ (Allport 1935:832). As soon as he found himself in the domain of intelligence testing and Likert, the unconscious dimensions of the attitude seem to have been forgotten and remained forgotten for a significant period of time. Allport wanted to measure attitudes with precision and reliability, so he went for introspective paper and pencil-type tests. He clearly had his own objection to hypothesising scientifically about unknown and unknowable forces affecting our lives through the unconscious and, given Allport’s influence on the developing field of social psychology, the focus turned away from the unconscious to the conscious, and therefore to self-report-type measures. It stayed there for the next half-century and more.

So, perhaps not surprisingly, I decided to begin my research programme proper by measuring attitudes towards carbon footprint in the tradition of Gordon Allport and the great experimentalist social psychologists who have documented our attitudes for decades, using Likert scales to reveal consciously held attitudes. It was a safe and obvious bet.

What did we already know about environmental attitudes from the available sources? The picture in the published literature is very positive (indeed, almost too positive): generally speaking people say they are extremely concerned about the environment and really do want to make a difference (although some are more than a little confused about what carbon labelling actually means). Consider the short summary of previous research in Table 3.1, which seems quite typical:

Table 3.1 Explicit attitudes towards climate change and environmental behaviour

|

Explicit measure source |

Findings |

|

70% of people agree that if there is no change in the world, we will soon experience a major environmental crisis |

Downing and Ballantyne (2007) |

|

78% of people say that they are prepared to change their behaviour to help limit climate change |

Downing and Ballantyne (2007) |

|

85% of consumers want more information about the environmental impacts of products they buy |

Berry, Crossley and Jewell (2008) |

|

84% say retailers should do more to reduce the impact of production and transportation of their products on climate change |

Ipsos MORI (2008) |

|

Only 38% of the general public understand what ‘carbon labelling’ means |

Ipsos MORI (2008) |

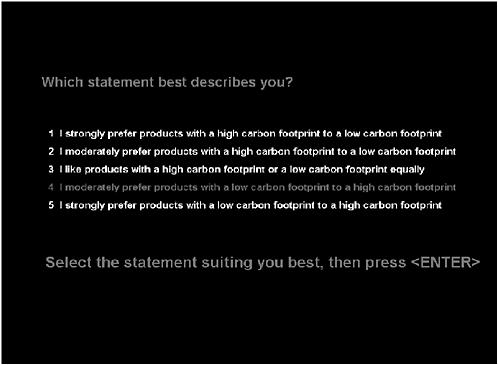

There seemed to be something of a clear consensus here, but what would my new research uncover? I used two measures - a computerised Likert scale and a ‘feeling thermometer’, which in this case would assess explicit feelings of warmth or coldness towards products with a high or low carbon footprint. The Likert scale gives a very simple measure of underlying attitude. A typical Likert scale is shown in Figure 3.1, and this is the computerised version we used in our actual research.

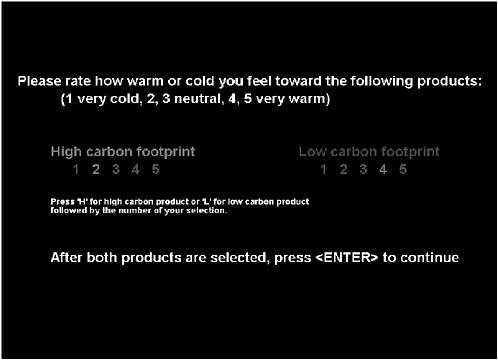

The feeling thermometer asked people to rate how warm or cold they felt towards high-carbon-footprint and low-carbon-footprint products and then the experimenter

Figure 3.1 A computerised version of the Likert scale for measuring attitudes to carbon footprint.

computed the difference between these two numbers. For example, someone with a very positive attitude to low-carbon-footprint products might tick ‘5’ meaning ‘very warm’ to the low-carbon-footprint products and ‘1’ meaning ‘very cold’ to the high-carbon-footprint products, and this would yield a thermometer difference score of ‘+4’. On the other hand, someone who had a very positive attitude towards high-carbon-footprint products might tick ‘5’ meaning ‘very warm’ on the high-carbon-footprint product and ‘1’ on the low-carbon-footprint product, thus producing a thermometer difference score of ‘-4’ (see Figure 3.2).

We found our first sample of participants for this research (Laura Sale was now officially my research assistant); we wanted to find a range of people of different ages and of different social backgrounds (not just the usual university students, but as usual somehow convenient for the environment of the university or college). Each participant was run individually and we had to do it this way to make sure that they knew what a carbon footprint actually was. In one

Figure 3.2 A computerised version of the feeling thermometer scale for measuring attitude towards high- and low-carbon-footprint products.

subsample of college kids, aged sixteen and upwards, we had to explain each time what a carbon footprint was before they could fill in the scale. Each time we administered the computerised test we had to check that they actually knew what they were rating. One seventeen-year-old lad interpreted the symbol quite literally (even after our introduction) and thought that it was the dent you made on the earth’s crust as you went about your everyday business. I never actually met this person and I thought that he had perhaps just a very visual way of understanding the nature of the world and how it works. Others were less kind.

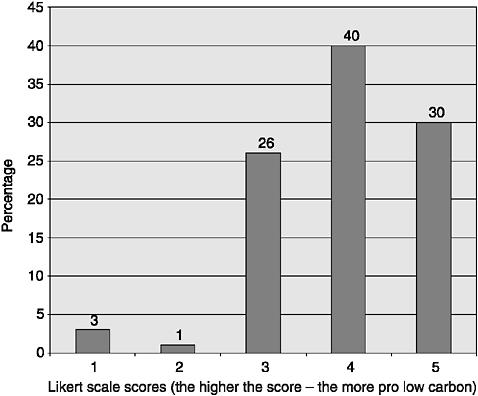

The results looked very promising. The Likert scale revealed that 30% of our participants demonstrated a preference for products with a low carbon footprint and 40% of participants demonstrated a moderate preference for products with a low carbon footprint; 26% of participants demonstrated no preference and only 4% demonstrated a preference for products with a high carbon footprint (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 Explicit attitudes to carbon footprint as revealed by the Likert scale.

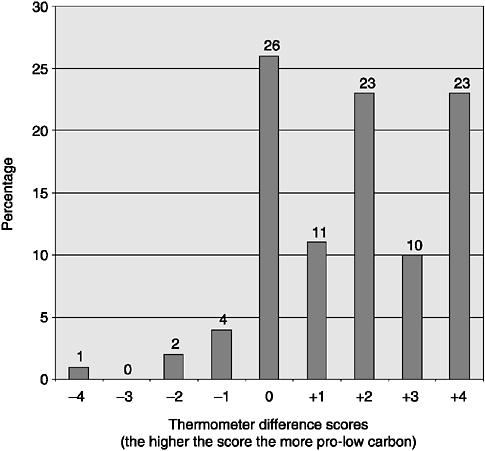

The feeling thermometer produced very similar results - 23% of participants showed a very strong preference for products with a low carbon footprint and an additional 40% showed some preference for low carbon products; 26% of participants were neutral in their attitudes (exactly the same figure as revealed by the Likert scale) and 7% of participants showed a preference for products with a high carbon footprint (see Figure 3.4).

These are clearly positive results, but just how positive depends on how you look at them. One way of looking at them (the way of the optimist) is to conclude that somewhere in the region of 67% to 70% of participants already show some significant preference for low-carbon-footprint products. The other way of looking at the data is that only 23% to 30% of people showed a strong preference for low-carbon-footprint products and that in reality we need to work on 70% of the population that are not sufficiently

Figure 3.4 Explicit attitudes to carbon footprint as revealed by the feeling thermometer.

concerned about this issue. But these results would suggest that underlying attitudes are very good.

However, there is a slight fly in the ointment that should be obvious to everyone. What happens if the expression of these attitudes is affected by the fact that everybody in our society knows that green is good? Even the lad who thought that the carbon footprint of a product reflected indentations on the earth’s crust still knew to say that low is good. How do we know that all of these easily expressed and deeply felt underlying attitudes are something more than the desire to look good in a research encounter?

We checked to see how people thought about those who cared for the environment and, not surprisingly, they thought in very positive terms about them. We found a new group of respondents and we asked them to describe the attributes of someone (1) who is environmentally friendly, (2) who is sensitive to carbon footprint and (3) who recycles, and we asked them to rate their judgement on a series of scales (from +3 to -3) - ‘considerate and inconsiderate’, ‘thoughtful and thoughtless’, ‘caring and uncaring’, ‘knowledgeable and ignorant’, ‘selfless and selfish’, and ‘nice and nasty’. The results are shown in Tables 3.2, 3.3 and 3.4and show a clear social desirability effect.

Who wouldn’t want to be seen as ‘considerate’ and ‘thoughtful’ and ‘knowledgeable’ and ‘nice’? In other words, people who are environmentally friendly are viewed in a positive light and the problem with this, of course, is that this social desirability, which is obviously very widespread

Table 3.2 Social judgements about people who are environmentally friendly

|

Attribute |

Mean |

|

|

✵ |

Considerate |

1.68 |

|

✵ |

Thoughtful |

1.64 |

|

✵ |

Caring |

1.27 |

|

✵ |

Knowledgeable |

1.14 |

|

✵ |

Selfless |

1.09 |

|

✵ |

Nice |

0.64 |

Table 3.3 Social judgements about people who are sensitive to a carbon footprint

|

Attribute |

Mean |

|

|

✵ |

Thoughtful |

1.41 |

|

✵ |

Considerate |

1.36 |

|

✵ |

Knowledgeable |

1.32 |

|

✵ |

Caring |

1.27 |

|

✵ |

Nice |

0.73 |

|

✵ |

Selfless |

0.68 |

Table 3.4 Social judgements about people who recycle.

|

Attribute |

Mean |

|

|

✵ |

Considerate |

1.64 |

|

✵ |

Thoughtful |

1.59 |

|

✵ |

Knowledgeable |

1.45 |

|

✵ |

Caring |

1.18 |

|

✵ |

Selfless |

0.91 |

|

✵ |

Nice |

0.59 |

throughout society, could potentially affect the expression of explicit attitudes towards environmental behaviour. In situations like this, it is clearly too risky to rest all conclusions on what people tell us either in interviews or even in the relevant anonymity of a computerised scale. People know that they are being judged: when you need to do research on a one-to-one basis there is always some kind of social bond between the researcher and the researched, and most human beings want to come across well. For these reasons and more I began to worry about how we get at underlying attitudes in situations like this. And then, of course, there was a more basic worry at the back of my mind - perhaps, after all, people do not know what their underlying attitude really is; perhaps Allport was wrong in the way that he developed the concept of attitude. Perhaps it does have its real roots in the unconscious. Perhaps he was right the first time when he wrote that ‘often an attitude seemed to have no representation in consciousness other than a vague sense of need, or some indefinite or un-analyzable feeling of doubt, assent, conviction, effort, or familiarity’ (Allport 1935:800). Perhaps this was what we had to try to measure. It turned out that I was not alone in my doubt; someone had got there long before me.