Higher: 100 Years of Boeing (2015)

8 The Queen of the Skies

The 747 earned the title “Queen of the Skies.”

Juan Trippe and Bill Allen had become good friends by the mid-1960s. The leaders of Pan Am and Boeing had conducted plenty of business together over the years, closing deals adding up to hundreds of millions of dollars. The two had even wagered a $25,000 bet on the delivery of Pan Am’s 707 jets. If the planes were delivered ahead of schedule, Allen won $25,000. Behind schedule, and Trippe got the money. It was Boeing’s president who cashed the check.

There were few subjects the men enjoyed talking about more than the aerospace business and the future of air travel. So it was not unusual that when these titans of industry were on a fishing trip, Trippe brought up Pan Am’s interest in flying bigger jet planes able to transport a larger volume of passengers. He could grasp the economics of such jets: lower aggregate costs per available seat mile due to greater fuel efficiency and higher passenger density, among other factors. This would encourage lower passenger fares, making air travel more affordable to the masses.

Allen was all ears. “Trippe told Bill, ‘If you build the airplane, I’ll buy it,’ ” said Boeing chief engineer Joe Sutter. “And Bill told him, ‘Well, if you buy it, I’ll build it.’ And they shook hands.”

The casualness of their agreement did not take into account the huge challenge that lay ahead: building the largest passenger jet in the history of the industry. At the time, the biggest planes carried no more than 250 people. Trippe was looking for a jet that would transport 450 passengers, nearly double that capacity. “They were as audacious as anybody who had ever lived,” said author Robert Daley. “Both would go bankrupt if they failed… . They were in over their heads.”

Allen tasked Sutter with leading the engineering effort to build the giant jet. Sutter quickly realized that the aerodynamics of an aircraft of the size Allen and Trippe wanted required a radically new type of plane. Unlike the 707, 727, and 737, the 747—the model number given the immense jet—would not be another iteration. It would be the first of its kind. “It wasn’t a minor step at all, it was a big step,” said Sutter.

Early meetings between Boeing engineers and Pan Am executives on the 747’s design did not go exactly as planned. In Trippe’s mind, a much larger aircraft meant a double-decker jet along the lines of London’s popular two-story buses. This concept was problematic, however. As Sutter explained to the Pan Am head at a meeting in Boston in 1965, two decks would create complications with evacuating passengers from the upper deck in an emergency. There also would be difficulties loading and unloading the galley, and very little room would be left for freight. Sutter lobbied for a different configuration: a wider fuselage instead of an elevated one.

To demonstrate how wide the plane’s cabin would be, Sutter and his fellow engineers brought along a 20-foot length of rope. They stretched it from one end of the hotel conference room to the other and then informed the Pan Am executives that they were sitting inside the wide-body jet. The engineers unveiled two mock-ups, one of Trippe’s requested double-decker and the other of the wide-body. “As soon as Juan Trippe saw the wide single deck, he changed his mind instantly,” Sutter said.

The design called for a twin-aisle jet with two and a half times the capacity of the Boeing 707. The aircraft would be as long as a city block and as tall as a six-story building. Its wingspan of nearly 196 feet would be more than half the length of a football field, or 76 feet longer than the distance traveled during the Wright brothers’ first flight. The jet’s maximum takeoff weight—735,000 pounds—would require an entirely new 16-wheel landing system to support its huge mass upon landing.

Longtime friends Boeing president Bill Allen (on the left) and Pan Am CEO Juan Trippe (at right) sealed the deal for the 747 with a handshake while on a fishing trip.

Inside the Boeing plant in Everett, Washington, the first 747 takes shape.

In April 1966, Trippe ordered 25 747s for roughly $525 million. To build a jet of such substantial proportions, Boeing required a more spacious manufacturing plant. In June 1966, the company purchased more than 750 acres of land adjacent to Paine Field in Everett, Washington, roughly 30 miles north of Seattle. More than 250 subcontractors and 2,800 construction workers cleared the dense forest, ultimately moving more earth than had been moved to build the Panama Canal and the Grand Coulee Dam—combined.

The plant was completed in less than a year. At 200 million cubic feet, it was the largest building in the world by volume and, with later additions, remains so today. Building the factory was pure misery. Two months of nonstop rain, followed by mudslides and snowstorms, challenged the workers. When the plant was finished, it was so voluminous that it actually generated its own weather. Clouds formed inside the building, requiring the installation of a state-of-the-art air circulation system.

Five months before the facility opened in May 1967, Boeing employees were already at work in Everett receiving supplies and construction materials, which were delivered via a five-mile railroad spur with the second steepest grade in the country. An army of more than 50,000 Boeing designers, engineers, scientists, mechanics, and administrators joined them in the new building. Boeing executive Malcolm Stamper, who led the project to build the 747, called them “the Incredibles.” The name stuck.

While the building and railroad spur construction was under way, the jet’s designers were at the drawing boards refining their plans. The initial design drew from a military cargo plane prototype created for a government-sponsored competition that Boeing lost to another manufacturer, Lockheed. The designers ultimately provided more than 75,000 drawings to Sutter and other key engineers to produce the final design. The jet had a main cabin with 10-abreast seating and a smaller upper deck, above the cockpit, reached by a spiral staircase. The latter was a consequence of the configuration of the cockpit, which was placed on a shortened upper deck so the jet’s nose could open as an optional loading door for oversize cargo. This accommodation gave the 747 fuselage its distinctive hump.

Needless to say, the small upper deck was of great appeal to Trippe. Although it was not the double-decker jet he originally had in mind, it nonetheless offered room for more passengers.

The aircraft’s large size required an exceptional engine. Eighty-seven tests of different engine configurations were undertaken, resulting in the failure of 60 engines. Boeing engineers finally found what they sought: the industry’s first high-bypass turbofan engine, manufactured by Pratt & Whitney. The unique engine delivered double the power of earlier turbofan engines yet consumed less than a third of the fuel.

The 747 also was the first aircraft designed with a new methodology called fault tree analysis, a deductive investigation in which the potential failure of a single part was microscopically analyzed to determine its impact on other systems. In testing the plane, Sutter estimated that his team conducted at least 14,000 hours of wind tunnel experiments using exact-scale nine-foot-long models of the jet, and they exhausted more than 10 million engineering labor hours in the endeavor.

Plans for each new iteration in the plane’s design landed on chief engineer Sutter’s desk with a thud. Trippe visited Everett many times to check on the jet’s progress and always left requesting a few additional design changes. The Incredibles took it in stride. “We were a team,” Sutter said. “We had a job to do. And people were here to get that job done.”

Not just a passenger plane, the 747 could carry a stunning amount of cargo; its design allowed for cargo to be loaded through the hinged nose of the plane.

The distinctive hump at the front of the 747 fuselage houses the cockpit and a short upper deck.

The engineers worked seven days a week, 10 hours a day to do it. “Instead of coming into an empty engineering office at six or seven in the morning, I’d find hundreds of engineers already here,” Sutter said. “At the end of the day, I didn’t walk out of an empty office.”

The endless design changes and scheduling complexities took their toll, creating huge budget overruns. Resources were stretched thin not just by the work on the 747 program, but also by Project Apollo and another major contract with the government to build a supersonic transport (SST) jet. Sutter continually requested that Allen provide more engineers for the 747, but none were available. Capital quickly evaporated, and the company had to reach out several times to its banking partners for additional funding. Anxiety levels soared. “It was literally a race against time to keep the company solvent and deliver the plane,” said author Clive Irving.

This race involved more than just Boeing personnel. Stamper had organized a vast subcontractor network to build different parts of the jets, involving thousands of suppliers in “one of the largest industrial efforts in history,” the Seattle Times reported.

Despite these many obstacles, the Incredibles ultimately pulled off a “heroic feat of engineering,” Irving said. They made the deadline with weeks to spare.

The new jet, which made its first flight in September 1968, became known as both the Queen of the Skies and the Jumbo Jet. Several configurations of the 747 were developed: an all-passenger jet, an all-cargo jet, a half-freight and half-passenger jet called a Combi, and a convertible model with the proportions of the seating versus the cargo holds directed by buyers. The convertible model was transformed from a passenger plane into a freighter by removing the seats and adding rollers to the floor to move cargo on pallets. Once Boeing filled Pan Am’s order, 26 other airlines also placed orders, totaling $3 billion, for 158 747s in all. As the Seattle Times reported, “They stepped up quickly … envisaging improved passenger appeal and airline economics with the giant super jet.”

Chief among these economics was the volume of passengers that could be flown in the plane—up to 490 people, although many buyers planned on a smaller 360-seat configuration, which was still twice the normal seating of a 707 or DC-8. To entice travelers, the same newspaper article noted, “The emphasis in 747 service will be on ‘living room comfort.’ ”

The 747 would prove to be Bill Allen’s crowning achievement. “He had the courage to go ahead with a project that would revolutionize air travel,” said Sutter. The jet’s radical size, shape, and technological ingenuity became an icon of the modern age. No other manufacturer made an airplane like it. The 747 also deepened impressions regarding what became recognized as one of Boeing’s core competencies: integrating large-scale systems involving thousands of people and parts. The 747 and the Apollo program were colossal achievements for a company that a little more than half a century earlier was making biplanes in a boathouse.

Yet at Boeing some considered the Queen of the Skies to be a less important endeavor than the company’s work on the proposed SST. Flying faster than the speed of sound, the supersonic jets were expected to attract numerous airline buyers interested in promoting shorter flight times to passengers. “Everyone figured the 747 would be an interim airplane until the supersonic jets took off,” said Sutter.

The 747’s range and high passenger capacity changed the way the world traveled, opening up affordable, long-distance flights to more people.

The 747 was known not only for its technological achievements, but also for its glamour. With a lounge, cocktail service, and sometimes even a piano, it held the promise of an elegant, relaxing travel experience (above and next).

The U.S. government had launched a competition in 1966 for a partially funded contract to build an American supersonic transport vehicle. Boeing had been studying the design and development of SSTs since 1952, and in 1958 it had established a permanent research committee to enrich these evaluations. On New Year’s Eve in 1966, the company received a belated Christmas gift: news that it had won the competition.

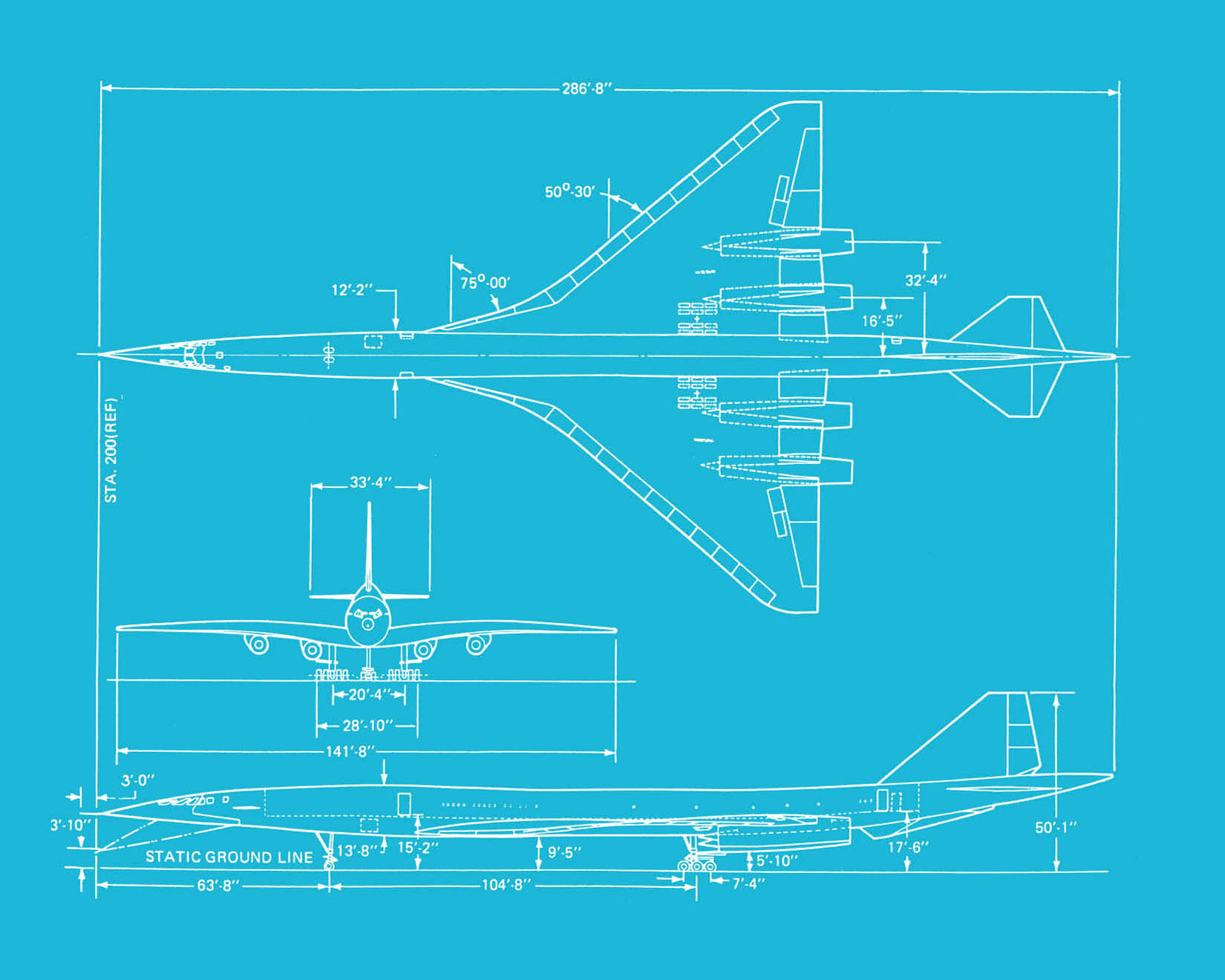

The mockup of the Boeing 2707-300, the model name for the SST, was 318 feet long and fronted by a double-jointed, needle-shaped nose that would drop during takeoff and landing for improved pilot visibility. It was large enough to seat as many as 300 passengers and could cruise at speeds in the range of Mach 2.7. These features made Boeing’s proposed aircraft much larger and significantly faster than competing designs like the Concorde, which was jointly developed by Aerospatiale and the British Aircraft Corporation. Once Boeing won the competition to design the aircraft, 26 airlines stepped up to order 122 of the jets. Along with the Apollo program and the 747, the SST associated Boeing in the public mind with unsurpassed technological ingenuity. The company’s future seemed boundless.

Similarly, McDonnell Aircraft’s F-4 Phantom II jet had established McDonnell as a company capable of technological leaps. But the mid-1960s

were a difficult period financially for the company, which suffered from cyclical downturns in military procurement. Douglas Aircraft also fared poorly, its narrow-body DC-8 jet at a disadvantage as the world’s airlines increasingly turned to wide-body aircraft.

Unlike Boeing, which had pursued a balanced postwar market diversification strategy, McDonnell and Douglas had tended to specialize in either military or commercial aircraft, not both. The two companies sounded each other out about a possible merger. Given McDonnell’s prowess making military aircraft and Douglas’s success with commercial airliners, they appeared to be a good fit. In 1967, they reached the decision to merge and combine the respective strengths of the two companies. The new McDonnell Douglas Corporation was run by Mr. Mac himself: 68-year-old James Smith McDonnell.

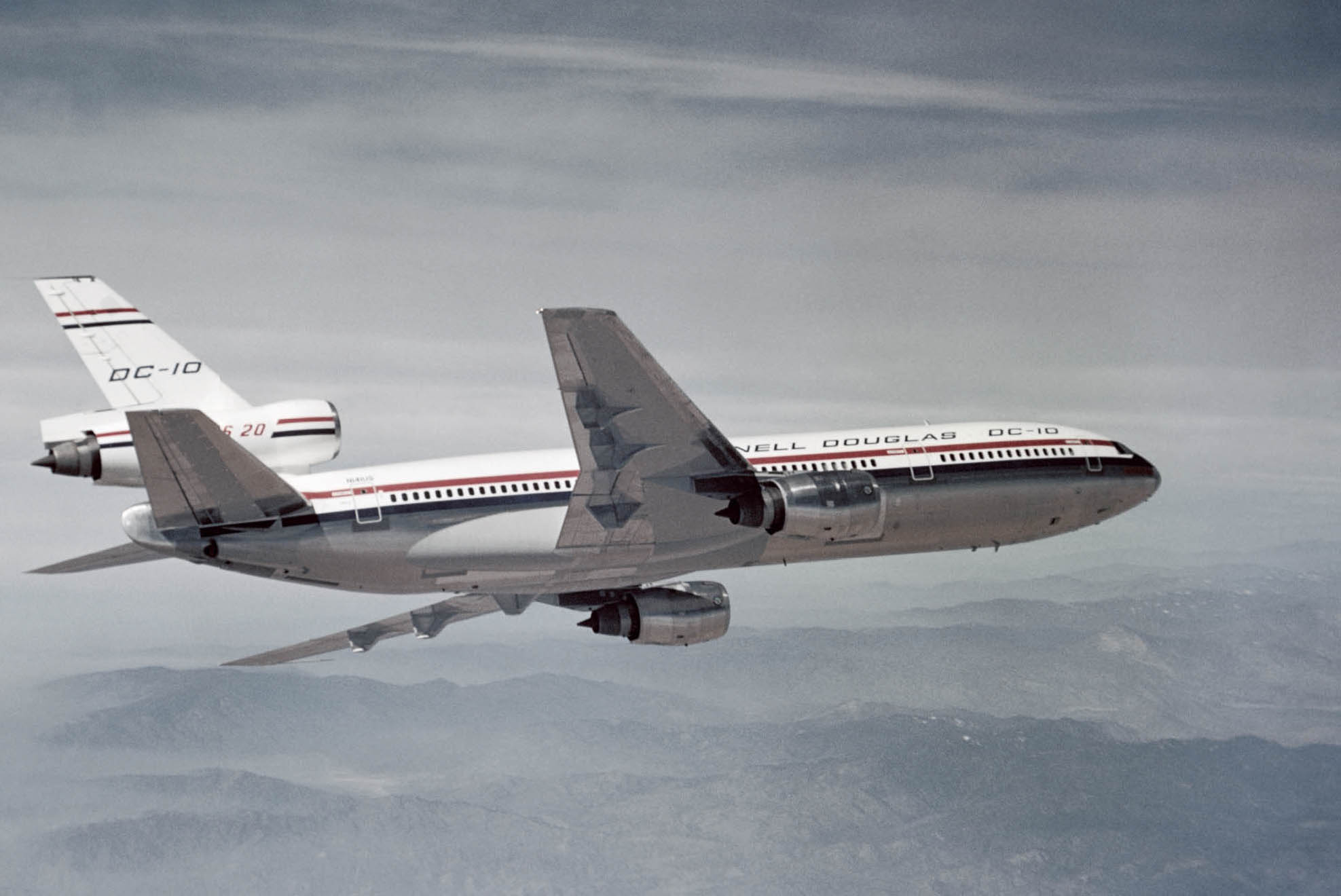

Three years later, McDonnell Douglas celebrated the maiden flight of its first wide-body jet, the DC-10, a three-engine plane capable of carrying a maximum of 380 passengers. Two years after the 747 was rolled out, Boeing’s wide-body had some real competition. Lockheed also entered the market with a wide-body trijet, the L-1011 TriStar.

American Airlines ordered 25 DC-10s; that order was followed by 30 orders from United Airlines. More than 440 DC-10s were delivered before the last one rolled off the assembly line in 1988.

North American Aviation also entered into a merger in 1967, in its case with Rockwell-Standard Corporation, which was primarily a supplier of automotive parts. After a series of subsequent mergers, the company ultimately became Rockwell International in 1973. During the previous decade, North American had introduced the XB-70 Valkyrie, a stiletto-shaped supersonic bomber designed to fly at three times the speed of sound. But the advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles and other developments rendered the project unnecessary before it went into production, and only two prototypes were made.

A CH-46A Sea Knight transfers cargo between two ships. Boeing transport helicopters such as the CH-46 Sea Knight and CH-47 Chinook carry out military and humanitarian missions around the world. The CH-47 serves the defense forces of 18 countries, including the United States.

After more than a decade of planning and competition, the contract for the supersonic transport (SST), shown in a schematic diagram and artist’s rendering, was awarded to Boeing in 1966. The program was canceled in 1971, before the first prototype was complete.

The F-4 Phantom II fighter first took to the skies in 1958 and was in service with the U.S. military for the next four decades. It served in both the Vietnam War and Operation Desert Storm.

As the 1970s commenced, the economic boom that had ignited in the postwar years fizzled for the entire aerospace industry. Boeing and other manufacturers were buffeted by a “perfect storm” of rising fuel costs, falling passenger revenue, and jetliner overcapacity. Carriers had simply bought too many planes, and many now sat idle. The industry had not experienced such difficult times since the Great Depression.

At Boeing, the impact was felt quickly. Fortunately, Thornton Wilson—or T. Wilson, as he preferred to be called—had succeeded Bill Allen as president of the company in 1968. (Allen became chairman of the board, a position he would occupy for the next four years until his retirement.) Although he took command at the pinnacle of Boeing’s success with the 747, Wilson turned out to be equally adept at steering the company through a storm. He was as straightforward, unassuming, and unpretentious as his predecessor, although his language was a bit saltier (more than once, Wilson’s remarks resulted in letters to the company scolding his use of swear words). An aeronautical engineer by training, he had hired on at Boeing in 1943, right after college, and later headed the company’s Minuteman missile program.

Wilson soon confronted substantial challenges. NASA temporarily halted progress on the Apollo space program. With the slowdown in airline orders, the financial outlook was bleak: Boeing’s earnings fell from $83 million in 1968 to approximately $10 million the following year. The pressure took a toll on Wilson, who suffered a near-fatal heart attack in January 1970. He considered retiring but decided to press on, despite the difficult decisions before him.

Over the next 22 months, Boeing’s workforce was slashed from 107,962 employees to 61,826. The layoffs had particular impact in Seattle, where the workforce fell from about 80,400 to approximately 37,200. The severe downsizing had an impact on the city’s morale; the mood was captured unnervingly by a billboard two real estate agents erected displaying the words “Will the last person leaving Seattle turn out the lights?”

The media were critical of the company’s perilous financial state. “Heady with euphoria of the early jet age in the 1960s, Boeing grew fat and sloppy,” Time magazine chided. “Seattle’s entire economy went into a slump.”

The final straw was the government’s decision in 1971 to no longer fund Boeing’s development of the SST, the project once deemed more important to Boeing’s future than the wide-body 747. Although airlines remained interested in the concept of supersonic travel, it received wide negative press. Environmental groups complained about the noise produced by the jet’s sonic boom and the impact the high amount of fuel it burned had on the ozone layer of the atmosphere. Rising alarm spurred public protests, prompting Congress to withdraw funding in 1971, before the Boeing prototype was ever finished.

Although the SST had consumed huge amounts of company resources and capital, Boeing had no recourse but to cancel the program. The SST became known as “the airplane that almost ate Seattle.” Today, what is left of the mock-up of the needle-nosed jet is in storage at the Museum of Flight’s restoration center in Everett. But the company never abandoned its research into supersonic flight.

Soaring inflation, interest rates, and unemployment gripped the United States, constraining economic growth. Business in each segment of aerospace—military, space, and commercial—fell fast. Struggling to pay for the long war in Southeast Asia and new social welfare programs, the U.S. government sharply curtailed military orders. The same factors slowed the sprinting Space Race to a walk. The passenger jet business was equally stagnant: instead of ordering new aircraft, major airlines held on to the planes they had to serve declining passenger loads.

Boeing’s formerly robust sales of 7-series jets were anemic. The company even endured an 18-month period, beginning in 1970, in which it did not receive a single airline order. “It was a matter of survival,” Wilson later told reporters.

To reduce corporate expenses, Wilson further pared the labor force to about 32,500 in 1971. Local media dubbed the severe downsizing the Great Boeing Bust. A familiar joke of the period was that a Boeing optimist brought lunch to work, while a pessimist left the car running in the parking lot. Even with substantial layoffs, analysts predicted the company was headed toward bankruptcy. Boeing survived from airplane delivery to airplane delivery.

The leaner company held on the best it could. Military programs such as Minuteman missiles and orders for Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft generated needed income. AWACS jets were modified 707s, with the military designation E-3, that carried surveillance radar and other systems to detect and track both airborne and maritime targets more than 200 miles away. The radar was housed in a 30-foot-diameter rotodome, which resembled a giant Frisbee mounted on two struts over the fuselage.

Boeing’s various diversifications also buttressed the bottom line. Boeing Vertol in Philadelphia, which usually manufactured military helicopters, received a contract to build light rail vehicles in Boston and San Francisco and rapid transit cars in Chicago. Boeing Engineering and Construction built large wind turbines for the Columbia River Gorge in Washington State, and Boeing Marine Systems manufactured commercial and military hydrofoils. The company’s 13 different computing organizations, each supporting different operations, were combined in 1970 as Boeing Computer Services, an independent subsidiary that would develop an extraordinary range of communications and information technologies in the years ahead.

Other ventures included managing housing projects for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, converting seawater to freshwater for a Virgin Islands resort, and building radio transmission voice scramblers for police departments. Although these contracts and others provided much-needed income, they were a far cry from the large orders of military jets and passenger airliners from previous years.

The company’s biggest asset during this bleak period turned out to be Wilson, who remained optimistic and confident the company would weather the recession’s impact. Throughout the crisis, Wilson adhered to the company’s practices of innovation and long-term strategic planning. He put an enormous amount of capital—more than 7.6 percent of sales—into the research and development of future aviation technologies and products. Among these were satellites, which were just beginning to become a major market in the early 1970s. “When we get moving, watch out,” the ever-upbeat Wilson said.

During the 1960s, Boeing had demonstrated again that it could envision the impossible and then create it. The 747 program had used all of the company’s trademark skills: a knack for tackling intensely complex projects, the ability to meet near-impossible expectations, and a passion for creating the best aerospace vehicles. For the time being, however, Boeing’s primary enterprises were in a holding pattern.

McDonnell Douglas’s first wide-body jetliner, the three-engine DC-10, has accumulated more than 25 million hours of revenue travel since its inaugural flight on August 29, 1970.