Higher: 100 Years of Boeing (2015)

10 Boeing Today and Tomorrow

The 787 Dreamliner has set a new standard for comfort and efficiency in commercial flight.

After the historic mergers and acquisitions of the 1990s, Boeing’s vast workforce stretched across all 50 U.S. states and more than 65 countries. The company had to manage the internal challenges of combining diverse product lines, business processes, and people to succeed in the new era of globalization—with competitors snapping at its heels.

Globalization meant far more than merely selling products to international customers or establishing operations in these countries. The company had to move beyond just conducting commercial transactions toward engaging in a true partnership with its foreign customers and suppliers, becoming more a part of the cultural fabric of the communities with which it did business. Boeing’s aim was to make use of the best talent and resources available, no matter where they were located, to advance the company’s position at the forefront of innovation.

In this quest, Boeing worked to erase both organizational and geographical boundaries to bring together the ideas of talented people with different backgrounds and experiences across the enterprise. To enhance this global value creation, the company continued to engage in new acquisitions, partnerships, joint ventures, and supplier relationships.

Sending a clear message about the company’s new direction, Boeing made the decision in 2001 to relocate company headquarters to Chicago, separate from Boeing’s engineering and manufacturing centers in Seattle, St. Louis, and Southern California. The move signaled to the world that this was a new Boeing.

One of the first projects the new Boeing took on was development of a new commercial airplane—always a risky endeavor. “Commercial aerospace is not a business for the faint of heart,” said Harvard Business School professor Willy C. Shih. “The magnitude of investment in new aircraft programs exceeds $20 billion … basically ‘bet the company’ type investments where you may not earn a return for 15 or 20 years. When you get to 15 or 20 years, you’ll find out if you had the right product strategy. And if you’re wrong—that’s a bitter pill to swallow.”

Boeing and Airbus reached different conclusions about “the right product strategy.” Airbus committed to offering greater passenger capacity, convinced that airlines would continue to fly hub-to-hub routes and serve these hubs through a network of smaller regional routes. To this end, Airbus put the Queen of the Skies herself—Boeing’s prized 747 jumbo jet—in its crosshairs by launching the full-length, double-deck A380 superjumbo, which boasted a larger capacity and longer range than the 747.

Boeing took a different tack, emphasizing aircraft speed for swift point-to-point connections in its next-generation airliner, the proposed Sonic Cruiser. The jet was designed with a cruising speed of up to Mach 0.98 (just under the speed of sound) and a passenger capacity of 250. Its unusual design featured a delta wing and small wing-like canards toward the nose, giving it an arrow-like appearance.

A rendering of the Sonic Cruiser shows the conceptual aircraft in flight. The plane, which was intended to have a cruising speed of up to Mach .98, was discontinued when Boeing’s focus switched to development of the 787.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, brought these plans to a sudden halt. Both manufacturers soon confronted the harsh economic realities of the post-9/11 world. Stock markets worldwide suffered unprecedented drops. The price of fuel skyrocketed and the volume of travelers declined, causing several airlines to declare bankruptcy. The airline industry was in chaos.

Although the 9/11 attacks did a great deal of damage to the commercial aviation side of the business, Boeing’s acquisitions of the previous decade helped mitigate the effect on the overall enterprise. Declines in the airline industry were counterbalanced by sharp increases in military spending, a trend that continued for more than a decade. Contracts for military aircraft and systems such as the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) weapon system, C-17 Globemaster III transport, F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and F-15E Strike Eagle fighters, and CH-47 Chinook and AH-64 Apache helicopters kept the company on course.

Likewise, the company remained a crucial partner to NASA in programs such as the International Space Station—unquestionably the greatest international cooperative venture in the history of science, technology, and engineering. In addition to designing and building the laboratory module and other major U.S. components of the space station, Boeing was responsible for integration of the hardware and software coming from its many international partners. This meant ensuring that the pieces of the station that were constructed on the ground and transported into space would fit together and function perfectly the first time, a task that made the most of Boeing’s proficiency in large-scale systems integration.

While defense forces around the world ramped up and engaged in the global war on terrorism, the airline industry began to regroup. The carriers that remained in operation had little interest in superjumbos like the A380 because of their high operating costs and limited route flexibility. Rather, they sought next-generation aircraft that could do two things much better than current planes could: travel farther on a tank of gas and do so at lower operating costs. Economics became the driver.

Boeing abandoned the Sonic Cruiser design but not its conviction that passengers preferred to fly point-to-point rather than connect through hubs. Opportunely, the company had been simultaneously developing another type of aircraft using the same technology as the Sonic Cruiser—a conventionally configured yet super-efficient jetliner known initially as the 7E7 (the E stood for “efficiency,” among other things).

As work proceeded, the plane was redesignated the 787. It also became the first Boeing commercial airliner in decades to be given a name as well as a number. In 2003, more than half a million people all over the world voted online to choose a name. The winner, Dreamliner, echoed the name of the classic Boeing Stratoliner, the first plane to enter service with a pressurized cabin years before.

The name signaled that, standard appearance aside, the 787 would be a revolutionary airplane using new materials, aircraft systems, and production methods. More important, it would meet airlines’ need for a plane that used less fuel while also flying longer routes, reducing environmental impact, and creating a more comfortable flying experience for passengers.

It was an audacious objective, one that would call for the best efforts of Boeing’s workforce and an international network of suppliers and partners. And it would be guided by new Boeing chairman and CEO Jim McNerney, who was named to those positions in 2005 after a series of ethics scandals had led to the departure of previous senior executives.

McNerney represented a fresh start for Boeing as the first company leader since Bill Allen to be brought in from outside the organization. At the same time, he was familiar with the industry, having previously led the aircraft engines division of General Electric, and with the company, having served on the Boeing board of directors while he was chairman and CEO of 3M. It was up to the new CEO to establish future strategy, inspire confidence in his mission, and renew the trust of the workforce and Boeing’s global partners.

Like other company leaders at critical junctures in Boeing’s history, McNerney was both prepared for and energized by the challenging duties in front of him. He applied his extensive management experience to operating Boeing more efficiently as a business and unifying the global enterprise into what he called “One Boeing.” Such unification was especially needed as Boeing undertook the development of its next commercial airplane—a complex global production effort like no other in the industry’s history.

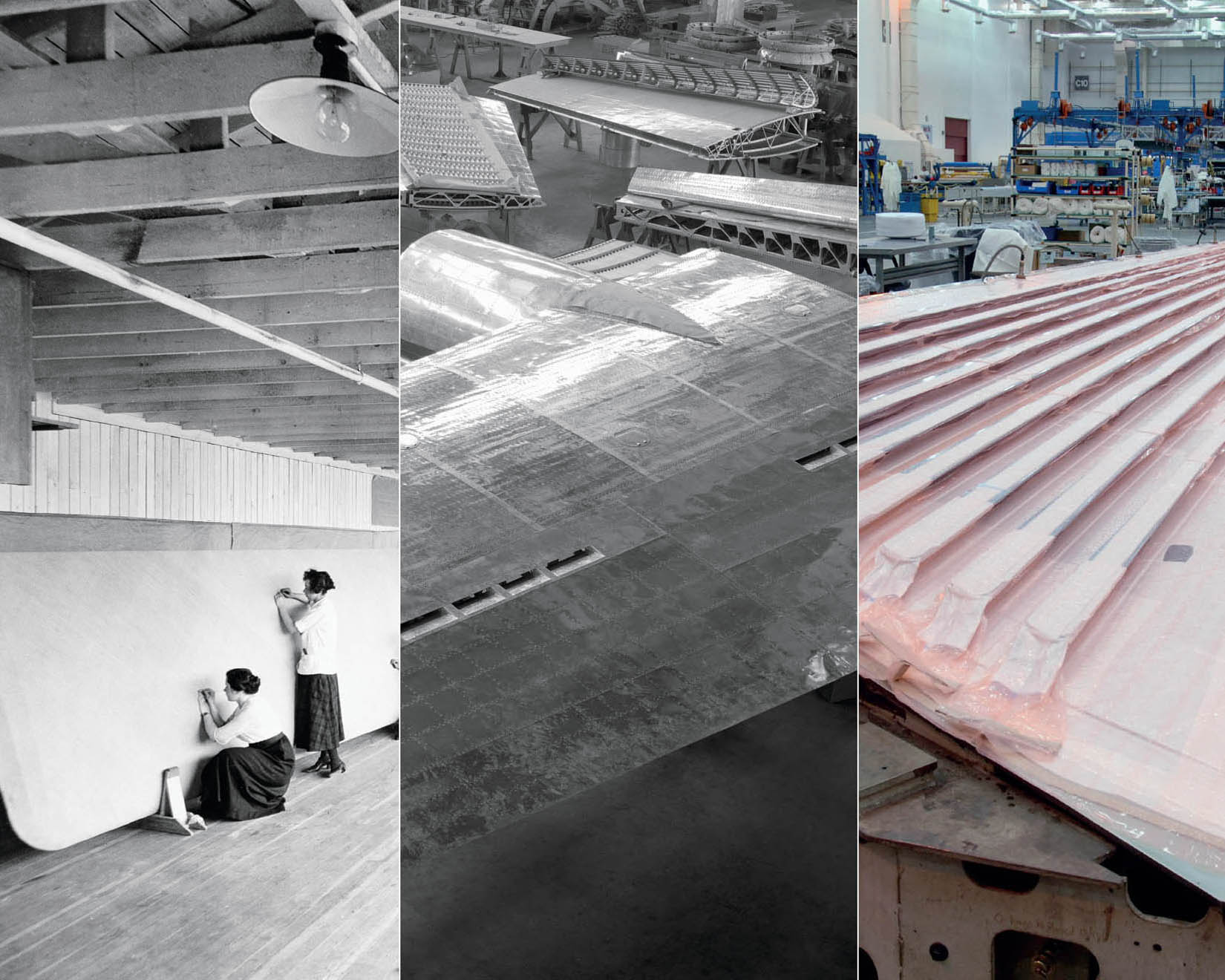

From wood and cloth to metal to carbon-fiber composites, the physical makeup of airplanes has changed as dramatically as the industry.

The 787 Dreamliner takes off for the first time as a crowd of employees and media looks on.

To reduce the weight of the 787, Boeing engineers planned to use composite structural materials to a greater extent than ever before. The 787 represented a reinvention of airplane composition—the second such reinvention in company history. In 1933, Boeing had introduced the first all-metal Model 247, replacing the wood, wire, and muslin planes of the past. Since then, almost all planes had been made of a metal fuselage and metal wings. But that was about to change.

Although the company had successfully used composites in the tail of the 777 and the structures of several military aircraft, Boeing had to assuage potential customer concerns over the use of composite materials in the new jet’s fuselage and wings. The overarching question was: would the airlines accept a passenger jetliner made with such a large proportion of unconventional materials?

The company responded creatively to the challenge. While airline executives watched, Boeing representatives took a sledgehammer to a sheet of lightweight composite material. It did not fracture or even chip, alleviating the executives’ apprehensions.

Building on their experience with using new materials and computer-aided design and manufacturing on the 777, Boeing engineers designed the 787 airframe so that nearly half the structure was made from carbon fiber—reinforced plastics and other composites, strong, lightweight materials that allowed for an average 20 percent reduction in aircraft weight compared to more conventional designs.

Manufacturing the composites was as challenging as designing them. Boeing’s embrace of globalization allowed an industry-wide collaboration by a multitude of suppliers worldwide, all of them collaborating according to the most stringent timetables. Large composite structures from all over the world were shipped to plants in Charleston, South Carolina, and Everett, Washington, for final assembly.

“Sixty-five percent of the parts were coming in from abroad,” said aviation writer Guy Norris. “You’re looking at supplies from all around the world … that finally have to wind up on that airplane on that day at exactly the right time, in the right sequence. It was a fantastic program and truly representative of the industrial-scale change that Boeing was undertaking.”

Many modules, such as the fuselage barrel sections, were extremely large. Ordinarily, these gigantic components would be transported by ship, but this process would take much too long for Boeing to maintain its production schedule. To solve the challenge, the company modified a fleet of four wide-body 747-400 cargo jets, based on a conversion design produced by Boeing’s engineering bureau in Moscow, Russia. The company called the cargo freighters Dreamlifters. The Dreamlifters, all of which were operational by 2010, succeeded in their purpose: delivering wings and fuselage barrels built by supply partners in Japan and Italy, respectively, in just hours, as opposed to the more than 30 days it normally took by ship.

An army of international players came together as One Boeing to create the 787. When the first Dreamliner rolled out of production on July 8, 2007, the milestone was marked with a ceremony attended by roughly 15,000 employees, airline customers, supplier partners, and government dignitaries.

Novel features on the 787 include larger windows that can be dimmed electronically.

Advanced aerodynamics, propulsion, and electrical power systems increase efficiency and comfort, while reducing noise and emissions.

Once complete, the Dreamliner delivered what airlines wanted: a midsize airplane with the range of a big jet, at 20 percent lower fuel consumption and with more cargo revenue capacity than comparably sized aircraft. For passengers, the 787 offered a more comfortable interior that conveyed feelings of spaciousness with higher ceilings, enhanced lighting, increased humidity, and a two-stage cabin air filtration system. Larger windows with novel window dimmers provided near-panoramic views of the horizon.

Newspapers and magazines trumpeted the new jet as a quantum leap forward in aircraft technology. By 2014, the three configurations of the 787 had captured more than 1,000 orders from airlines and leasing companies around the world.

Not everything went smoothly with the delivery of the first Dreamliner. A series of unexpected manufacturing problems led to a three-year delay before the jet finally was delivered to launch customer All Nippon Airways in September 2011. Even after the first planes were delivered, the fleet was grounded for a four-month period due to issues with the innovative lithium-ion batteries.

Once these problems were resolved, the 787 was soon in regular operation with airlines around the world. The new aircraft received high marks from passengers. Boeing quickly ramped up production, turning out more than 10 Dreamliners per month by 2014.

While production of the 787 was picking up, the military side of Boeing saw a downturn because of cuts in U.S. defense spending. As a result of these cuts, Boeing ceased production of the Collier Award—winning C-17 Globemaster III. However, employment reductions on the defense side were nearly matched by increases in the commercial business.

The company also continued to be active in space exploration and launch systems. In 2006, Boeing and Lockheed Martin became partners in the United Launch Alliance, providing launch services to NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense. The program, which uses Boeing Delta II and Delta IV launch vehicles as well as Atlas V rockets, has sent more than 90 objects into space, including telecommunications satellites and the NASA Mars Exploration Rovers.

As Boeing concludes its first century, it has a balanced, diversified portfolio of products and programs. Using lessons from the development of the 787, the company is refreshing its entire commercial airplane family with offerings such as the 747-8 Intercontinental, 737 MAX, and 777X that provide airlines with greater fuel efficiency and passengers with more comfort. Orders have been robust; in 2013, Boeing booked 1,355 net orders, the second highest number in company history.

Asian markets represent a huge opportunity for Boeing. China is expected to be the world’s single largest purchaser of Boeing aircraft in the next two decades, projected to buy as many as 6,000 new jets at a combined value of approximately $780 billion. The company has sold aircraft to China since President Richard Nixon’s historic 1972 visit to the country resulted in a deal for China to buy 10 707s. Boeing has maintained strong relations with the country, assisting in the building of its aerospace infrastructure, helping train its pilots, and guiding its regulatory equivalent of the FAA. Although China has ambitions to become a competitor at some point, Boeing’s preeminent technologies and unparalleled skill sets have given the company a long lead.

The 787 Dreamliner, with components made all over the world, exemplifies the globalization of the aviation industry. The Dreamlifter is a specially modified 747 cargo jet that is large enough to carry 787 wings and fuselages from overseas to the United States for final assembly.

On the defense side, Boeing continues to be the nation’s number-two contractor, managing a diverse portfolio of programs with U.S. and international governments for leading-edge fighters, helicopters, and launch systems—as well as newer endeavors such as cybersecurity and global support and logistics that are a natural extension of the company’s expertise in computing and large-scale systems integration. Looking to the future, Boeing and Lockheed Martin are following up their successful partnership on the U.S. Air Force F-22 Raptor tactical fighter by teaming up for the Air Force’s Long-Range Strike Bomber competition.

In addition to conventional fighters and other aircraft, Boeing is now providing an important new tool in the U.S. Navy’s defense arsenal: the P-8 Poseidon, nicknamed the “sub hunter,” a military derivative of the 737-800 (with 737-900 wings) designed to conduct anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface warfare, shipping interdiction, and electronic signals intelligence. Another commercial-defense crossover is the Boeing KC-46 Pegasus aerial tanker for the U.S. Air Force, derived from the venerable 767 jetliner.

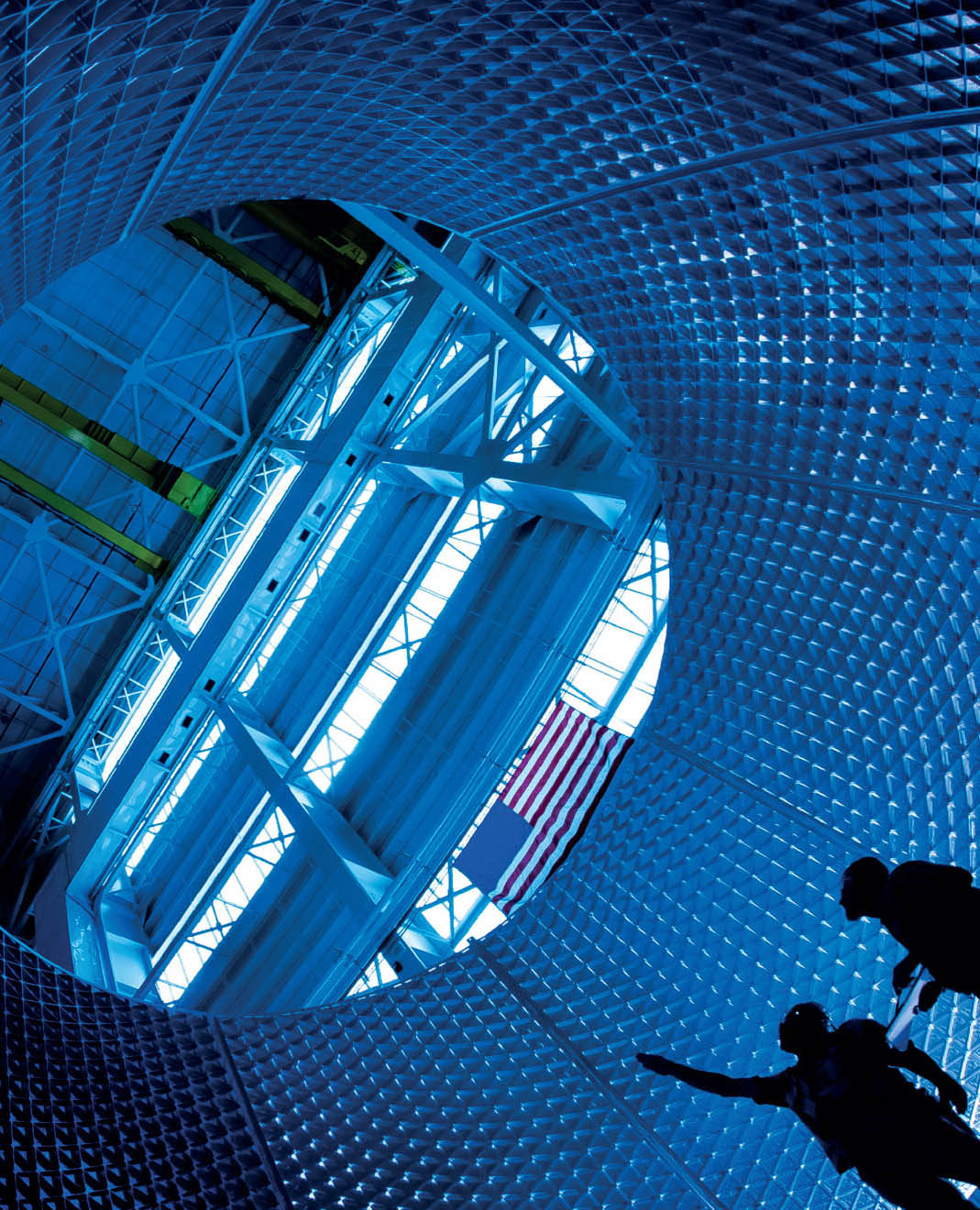

Boeing continues to pursue innovative technologies that will enable humankind to fly higher, farther, and faster. Boeing’s Phantom Works division, whose name echoes that of the famous F-4 Phantom II combat jet, is the advanced prototyping arm of the company’s defense and security enterprises. The division gathers wide-ranging skill sets from throughout the global enterprise for a single purpose: to break through technological barriers to develop singular technologies into prototypes. If all goes according to plan, these prototypes are then transformed into actual products.

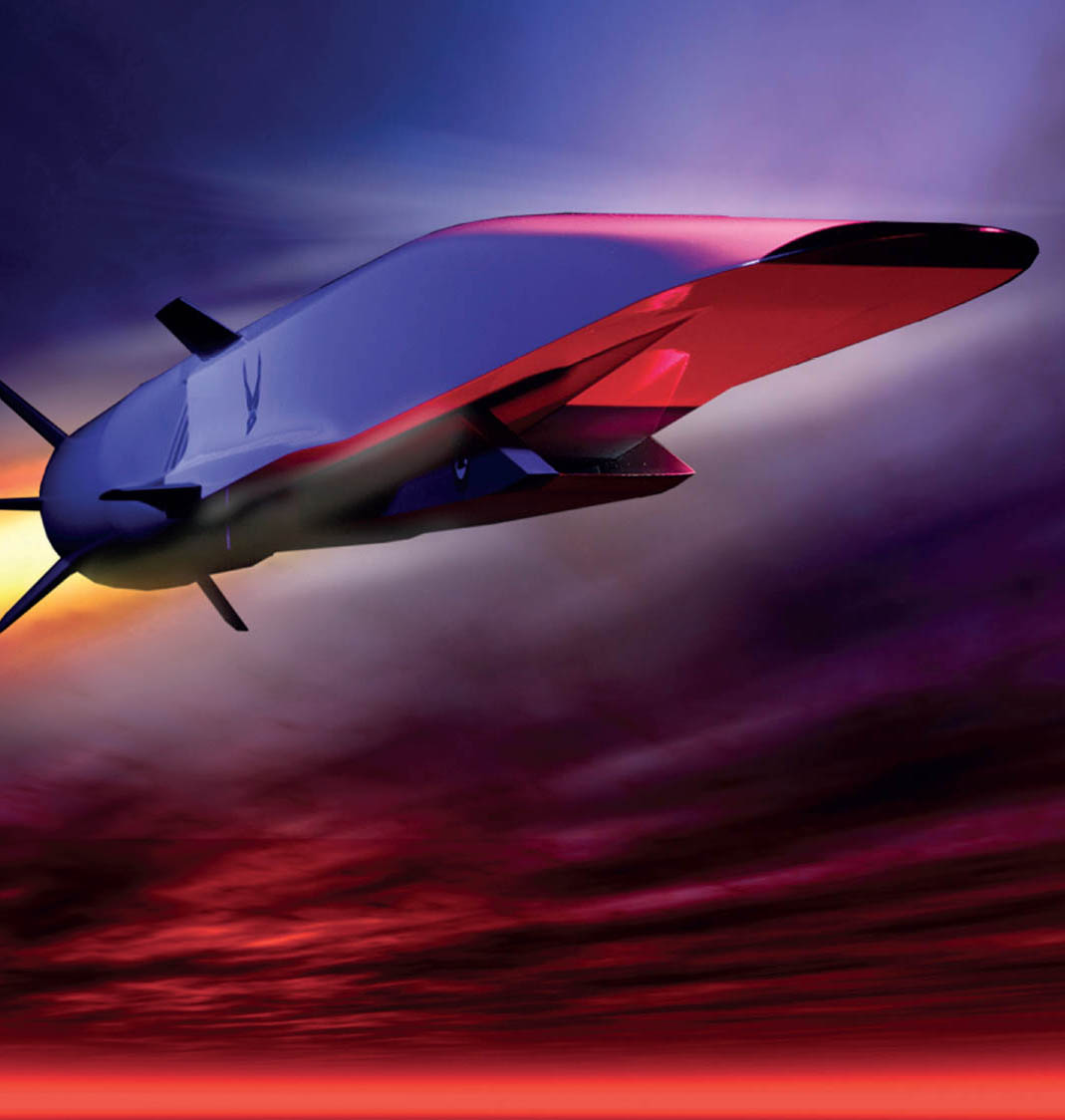

One such prototype from Phantom Works is the Boeing Phantom Eye, a high-altitude, long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) designed to provide advanced intelligence and reconnaissance. Phantom Eye uses a liquid hydrogen propulsion system to achieve flights of up to four days at high altitude. Another revolutionary concept is the X-51 WaveRider, an experimental UAV whose name derives from its inventive use of sonic shock waves to add lift to the aircraft. A supersonic combustion ramjet engine called a scramjet powers the UAV, using hydrocarbon fuel to reach hypersonic speeds (Mach 5 and higher). Unlike conventional rocket engines, the scramjet engine does not require oxygen tanks, instead harvesting oxygen as it flies through the atmosphere.

In 2013, the X-51 reached Mach 5.1, approximately 4,000 miles per hour, flying over the Pacific Ocean. With experimental tests now successfully concluded, its legacy is the depth of knowledge it is providing to scientists designing and developing hypersonic aircraft for the future.

“We’re extremely excited about it,” said former U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General David Deptula. “If you can fly at hypersonic speeds for minutes and then can do [the same thing for] hours, it [creates] the ability to get anywhere on the surface of the Earth rapidly, which opens up an entirely new spectrum of capabilities.”

An equally important initiative at Boeing is the creation of cleaner, more efficient products. Boeing is leading a global aerospace industry effort to develop more sustainable aviation biofuels that reduce carbon emissions and the industry’s reliance on fossil fuels. Under a contract with NASA, Boeing also is conducting research for the Subsonic Ultra Green Aircraft Research (SUGAR) program, developing the SUGAR Volt concept vehicle, a twin-engine aircraft that uses hybrid electric engines and an innovative truss-based wing to decrease fuel consumption.

The KC-46A Pegasus extends Boeing’s 50-year franchise in aerial refueling tankers, which began with a modified B-29 Superfortress.

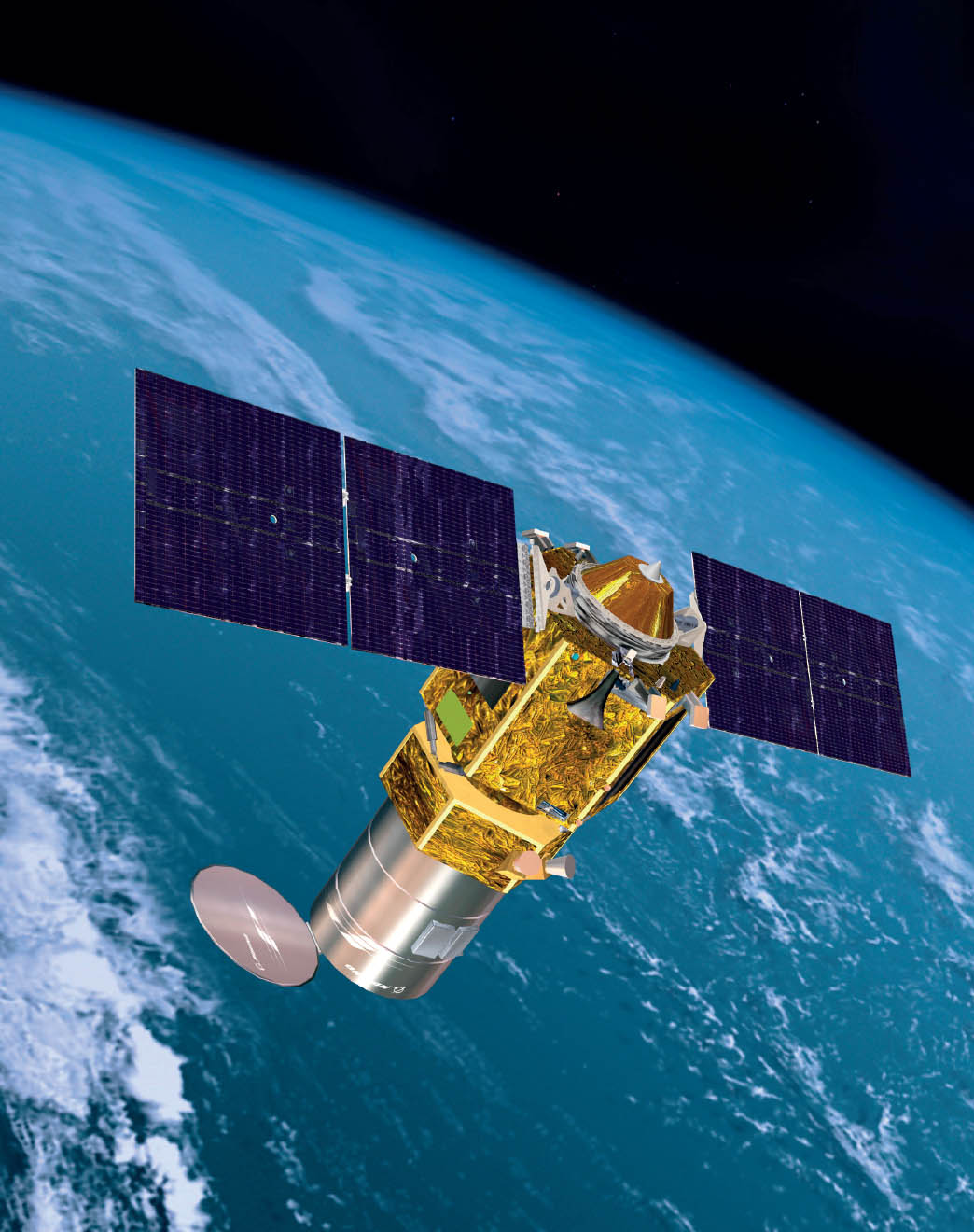

The Boeing 502 small satellite, seen above in an artist’s rendering, will carry the first high-resolution hyperspectral payload.

The Boeing Phantom Works X-51 WaveRider, an experimental unmanned aerial vehicle that uses its own hypersonic shock-waves for lift and travels at more than five times the speed of sound, is shown in an artist’s rendering.

Working in partnership with American Airlines and with funding from the Federal Aviation Administration, Boeing also converted a 737 jetliner into an ecoDemonstrator to test a variety of advanced technologies designed to reduce the environmental impact of commercial aircraft.

Years after the last shuttle flight, Boeing continues to be involved in manned and unmanned space exploration programs. The International Space Station supports a wide range of scientific experiments in micro-gravity conditions and is expected to be a gateway to deeper space destinations, including the moon and eventually Mars. The company’s contributions to research integration support and payload development services will enable the station to remain fully operational through 2024.

Boeing also has contracts to support work on the NASA Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV)—the next-generation manned spacecraft—as well as the new NASA Space Launch System (SLS) that will take Orion and its crew to the International Space Station, the moon, and even Mars.

In 2014, Boeing was selected by NASA to manufacture the CST-100 vehicle to transport passengers and cargo to the International Space Station and other planned commercial space stations in support of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Boeing space exploration engineers partnered with its commercial airplane designers to adapt the passenger-pleasing cabin layout and lighting of today’s Boeing airliners to the new space vehicle.

The company’s satellite business has progressed at a rapid pace in recent years. Since the beginning of the Global Positioning System (GPS) program in 1974, Boeing has built 40 of the 62 satellites launched in the series operated by the U.S. Air Force. In 2008, Boeing constructed a 20,500-square-foot satellite mission control center in El Segundo, California, to manage up to four commercial or government satellite missions at one time. Two years later, the company developed and built the first GPS IIF satellite, launched in May 2010 to enhance navigation and positioning accuracy on Earth. Boeing is under contract to build another 11 of the satellites.

Despite the U.S. aerospace industry’s consolidation following a historic spate of mergers and acquisitions, global competition is expected to increase. Although Boeing’s chief rival today in the commercial airliner space is Airbus, new competitors are emerging in Brazil, Russia, Japan, and China. On the military side, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman are Boeing’s top competitors, although there are other international players. With entrepreneurs including Richard Branson and Elon Musk now taking an interest in commercial space travel, Boeing has a potential new market—and new challengers.

In 2012, Boeing regained its market share leadership in commercial airplanes, which it had lost to Airbus in 2004. Today, Boeing is the world’s largest, most diverse aerospace company. A true global enterprise, Boeing continues to build strong business momentum across the world. “It used to be winning in America meant you won everywhere,” said Boeing chairman and CEO Jim McNerney. “Today, you have to win everywhere to win in America.”

The largest and most powerful rocket ever built, the Space Launch System (SLS) will enable NASA to make manned missions to Mars. Boeing is the primary contractor for the SLS core stage.

Phantom Eye is an unmanned reconnaissance vehicle powered by liquid hydrogen under development at Boeing Phantom Works. The larger scale version will eventually be capable of up to ten days of autonomous flight without refueling.

A century is a long time for any business to survive. For a company to thrive that long in the aerospace industry is an extraordinary achievement. From its humble beginnings in a boathouse, The Boeing Company has endured to become the world’s premier aerospace company, the largest manufacturer of commercial jetliners and military aircraft combined, and the United States’ biggest exporter. A company that once made biplanes of wood and fabric now manufactures jets of composite materials that didn’t exist a century ago. From a single customer in the U.S. government, Boeing now tallies thousands of customers in 145 countries.

Along the way, Boeing has pushed through boundaries that were thought to be impenetrable. The company led the manufacture of military aircraft in World War II and made good on a young American president’s plan to put humans on the moon. At great financial risk, it manufactured the first swept-wing jet and the wide-body Queen of the Skies. Even when it fell flat—when competitors beat it to the gate with a better model, when government regulations forced its hasty breakup, or when foreign policy and global economics conspired against its business—the people of Boeing persevered, learned from these setbacks, and did what they had set out to do: make better aircraft.

In the 100 years since Boeing opened for business, it has welcomed hundreds of thousands of workers. Indeed, the company’s long history has been shaped as much by these individuals’ ingenuity, dedication, and integrity as by their innovative solutions to vexing problems. Time and again, the company’s skilled leadership, ability to reposition quickly, employees’ can-do resolve, and passion to satisfy customer needs have lifted Boeing.

Since the dawn of the 20th century, Boeing has explored and embraced new technologies that improve the way we live, communicate, and travel. In the 21st century, last century’s aviation giants—Boeing, Douglas, McDonnell, North American, and Hughes, now united as a global enterprise—continue on this journey.

Bill Boeing first articulated the company’s basic philosophy a century ago: “We are embarked as pioneers upon a new science and industry in which our problems are so new and unusual that it behooves no one to dismiss any novel idea with the statement ‘It can’t be done.’ ” It is this philosophy that continues to drive Boeing today.

When complete, the 777X series (shown here in an artist’s rendering) will be the world’s largest and most-efficient twin-engine jet.