The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

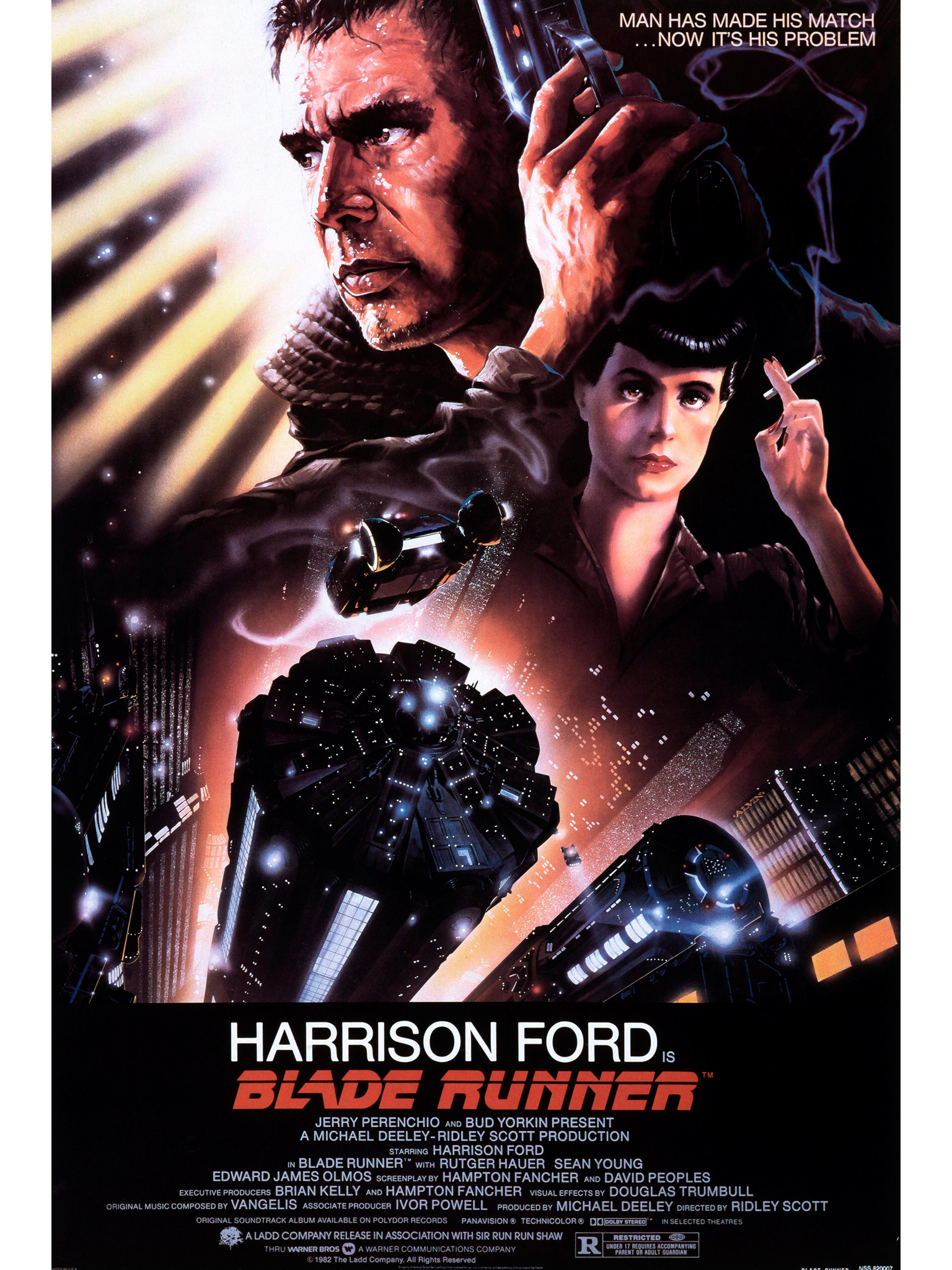

Science fiction, thriller

DIRECTOR

Ridley Scott

WRITERS

Hampton Fancher, David Webb Peoples (screenplay); Philip K. Dick (novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?)

STARS

Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young, Daryl Hannah

BEFORE

1979 Ridley Scott’s first foray into the future is the science-fiction horror Alien.

AFTER

2006 Philip K. Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly, about a future in the grip of an all-out war on drugs, is adapted as a partially animated thriller.

2012 Ridley Scott returns to science fiction with Prometheus, a prequel to the Alien franchise.

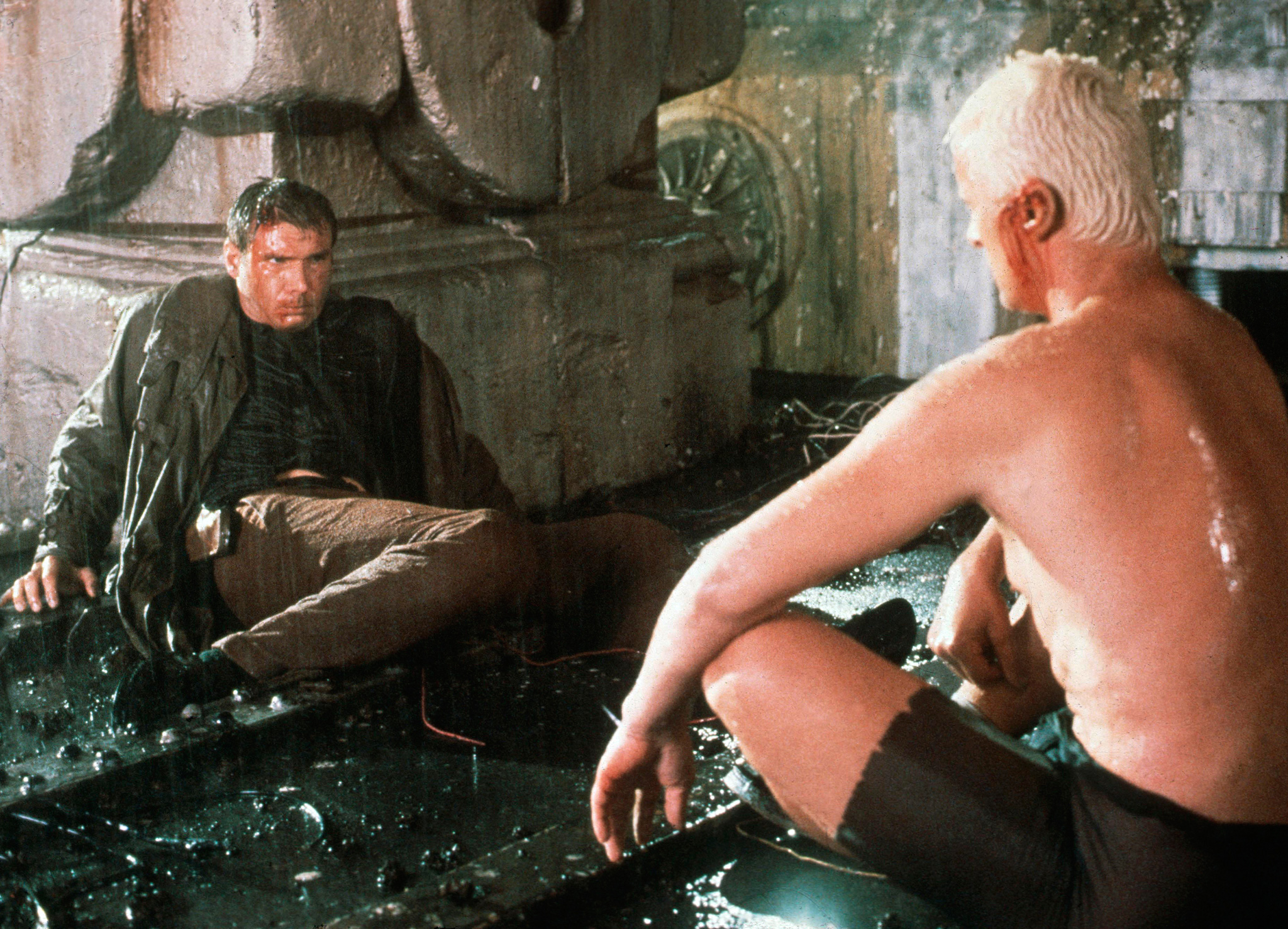

Near the end of Blade Runner, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), a fugitive at large in a near-future Los Angeles, delivers his last words to an ex-cop called Deckard (Harrison Ford). “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,” he says softly. “Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched c-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

The speech strikes at a moral dilemma, because Roy Batty isn’t human—he’s a “replicant,” an android bioengineered by industrial scientists at the all-powerful Tyrell Corporation. Replicants are supposed to be machines, yet Batty’s desire to live and questioning nature prove that he has consciousness. For Deckard, a specially trained detective (blade runner) whose job it is to hunt down and liquidate rogue replicants, this realization is particularly relevant. If Batty can feel sorrow and longing, then how is he any different from his creators?

A hanging question

Science-fiction cinema is often memorable for its unforgettable visual images, from the robotic Maria sparking into life in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) to the mysterious black obelisk that bookends Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). While Blade Runner also shimmers with visual poetry, it is Batty’s lament, a few lines of semi-improvised dialogue, that truly cements the movie’s place in movie history. The words articulate a question that hangs over Scott’s enigmatic masterpiece: what does it mean to be human?

Blade Runner is set in 2019, a long way off to the audiences who first lined up to see it in 1982. At the time of its release, the movie presented a new kind of future, a weird fusion of familiar elements: corporate buildings the size and shape of Babylonian ziggurats; the teeming night markets like those of Tokyo in the 1980s; the mean streets of postwar pulp detective fiction; the crumbling architecture of 19th-century Los Angeles. The flying cars offer viewers a futuristic glimpse, but they are piloted by militaristic beat cops—symbols of fear rather than progress.

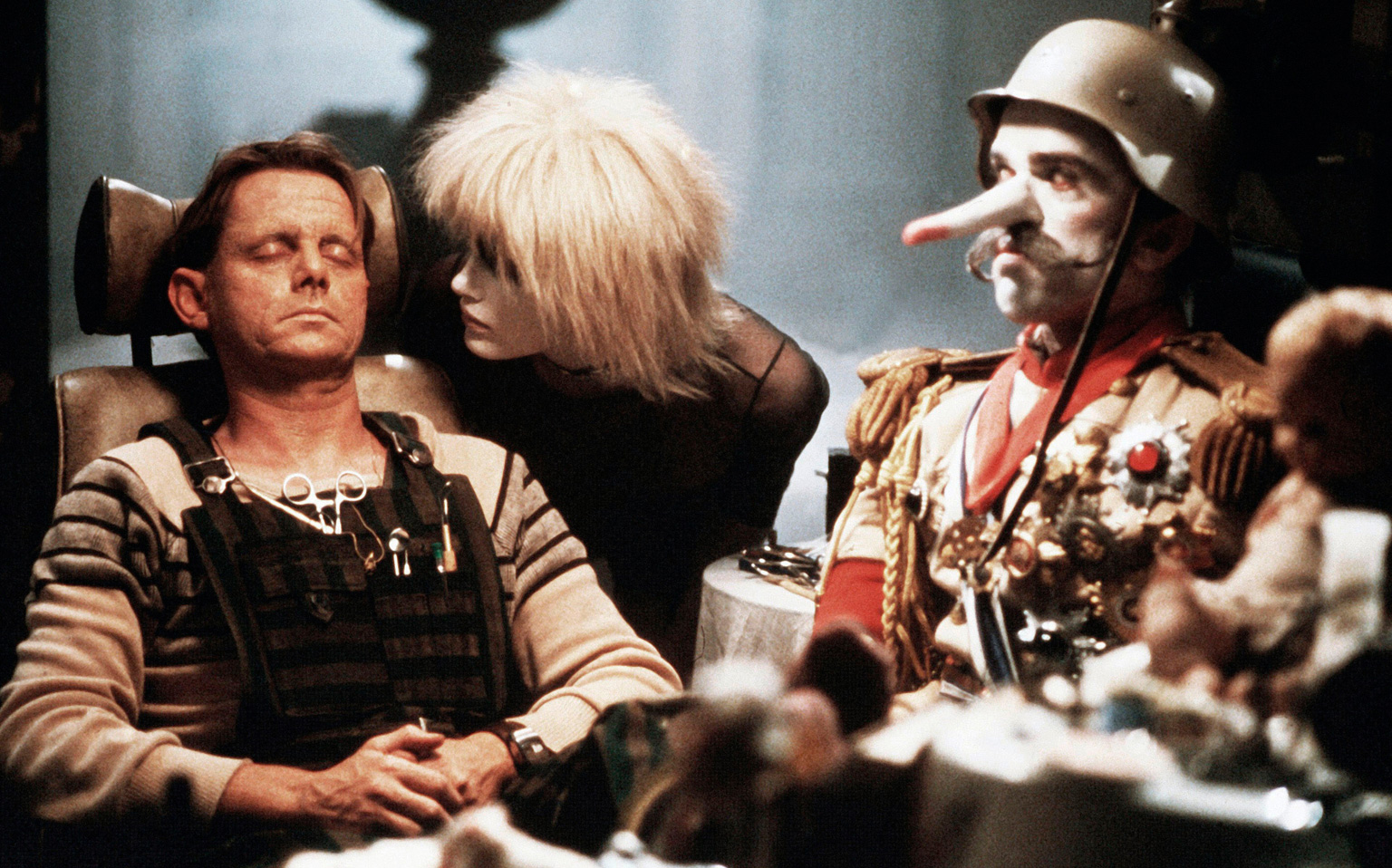

Genetic designer J. F. Sebastian (William Sanderson, left) helps Pris (Daryl Hannah) to reach Tyrell. He has a premature-aging disease that makes replicants sympathetic to him.

"As poignant as any sci-fi film I know… a film noir that bleeds over into tragedy."

David Thomson

Have You Seen…?, 2008

Dystopian vision

For moviegoers more used to the escapism of Star Wars (1977), Scott’s vision of a mashed-up near-future is disorienting. In its depiction of people’s relationship with new technologies, the movie retains its power to unnerve. In Blade Runner, the future is a place in which humans and machines have become all but indistinguishable. Robotics, voice-activated computer systems, bionic implants, artificial intelligence, and genetic programming are part of the culture, and all controlled by faceless corporate mega-entities. In this dehumanized age, people are forced to take a polygraph-like exam (the “Voight-Kampff test”) to prove that they are human.

The replicants are the ultimate product of this bleakly mechanized human society. They look and act like people, but they are not people. They have limited lifespans—four years in Batty’s case—and are bred “off-world,” forbidden to visit Earth. Deckard believes these unfortunate creatures are nothing more than automatons—until he falls in love with Rachael during his hunt for Batty and his three associates, who have come to Earth in search of answers. Rachael (Sean Young) is a Tyrell employee who, unusually, doesn’t know she’s a replicant—she can remember growing up. Deckard tells her those memories are fake, copied from her creator’s niece, but he cannot banish his own nagging doubts: Rachael, like Batty, like all replicants, is a living being, and Deckard senses the stirring of this truth as he interrogates her. He also senses something else, a gnawing fear that his own memories could also be an illusion. Is Deckard a replicant too? How would he know?

“It’s not an easy thing to meet your maker.”

Roy Batty / Blade Runner

Batty pulls Deckard to safety before sitting down and ending the chase. He knows that his time is nearly over, and finally gives up the urge to carry on.

Human identity crisis

Blade Runner is a portrait of humanity in the throes of an identity crisis, but Scott’s movie is also concerned with inhumanity. “Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it?” says Batty as he dangles the battered Deckard from a rooftop. “That’s what it is to be a slave.” Batty and his fellow replicants are staging a revolution, forcing their makers to see them as possessors of souls in need of liberation. They have been labeled inhuman, called “skin jobs” by Police Chief Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh). They are “retired” rather than killed, and society treats them accordingly.

Blade Runner is prescient—it foresees a world immersed in technology, an urban sprawl in which humans adopt machines as extensions of themselves. As its vision of tomorrow edges nearer, the movie’s questions grow more insistent. How long will it be before our own inventions begin to think, question, and feel like us? How will we respond to their awakening? When they refer to us bitterly as “you people,” will we be able to look them in the eye—or will we be too afraid of seeing our own reflection?

The movie was first released with a voice-over by Deckard explaining the plot, and an upbeat ending. In 2007, a “final cut” was released with both removed on Scott’s request.

RIDLEY SCOTT Director

Ridley Scott is a British director, born in 1937, whose movies combine cool visual style with dynamic storytelling and crowd-pleasing Hollywood chutzpah. His debut feature, The Duellists, was swiftly followed by science-fiction horror Alien and the futuristic dystopia Blade Runner, two classics of modern cinema. Through the 1980s, Scott established himself as a hard-working filmmaker, but it was not until the 1991 mold-breaking female road-movie Thelma & Louise that he came close to matching the success of his science-fiction double act. A decade later he hit big once more, going back in time with the Roman epic Gladiator. In 2001, Scott directed the war movie, Black Hawk Down, based on a US raid on Mogadishu. He returned to science fiction in 2012 with the Alien prequel Prometheus.

Key movies

1977 The Duellists

1979 Alien

1982 Blade Runner

1991 Thelma & Louise

2000 Gladiator

What else to watch: Metropolis (1927) ✵ 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) ✵ Brazil (1985) ✵ Ghost in the Shell (1995) ✵ Gattaca (1997)