The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

INTRODUCTION

Released in the last moments of the 1950s, François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows was the bridge into the decade to come, and the seismic shake ups that would arrive with it. From the very beginning of the 1960s, cinema was, like its audience, set on breaking rules.

New Wave

The impetus came from Europe, in particular from France, where Truffaut’s colleagues from the movie magazine Cahiers du Cinéma were creating a whole new language for movies. The era of the Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) would be embodied by director Jean-Luc Godard, a gifted ball of mischief who would release his own first feature in 1960: À bout de souffle (Breathless). Stylish and extremely witty, it immediately made everything that had come before look hopelessly old-fashioned.

All this was at a time when many observers thought cinema was dying, doomed by the spread of TV in Western homes during the 1950s. Cinema’s response was thrilling. Many of the greatest movies of the era were born out of a mood of bubbling outrage. In the US, the young genius Stanley Kubrick took a jab at the ongoing insanity of the Cold War with Dr. Strangelove, in which Peter Sellers paid homage to Alec Guinness’s multitasking in Kind Hearts and Coronets by playing three different characters. Later, as demands for change coursed around the world, the Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo would influence a generation of filmmakers with the incendiary The Battle of Algiers.

"The film of tomorrow will be directed by artists for whom shooting a film constitutes a wonderful and thrilling adventure."

François Truffaut

Counterculture

Elsewhere, the politics were less overt but the air just as thick with restlessness and the rejection of old orders. In Britain, another New Wave made hard-edged portraits of working-class life, such as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. And a new, boldly unsqueamish attitude to screen violence took hold as the decade went on. Taking its cues from Godard and its story from the lives of two wild young outlaws in the Great Depression, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde set a benchmark of stylized bloodshed.

While the movies got on with what they had always done best—entertaining mass audiences—some filmmakers also tapped into the avant-garde and upended ideas of what a movie was. From the post-nuclear time-travel feature La jetée (The Pier, 1962), made up almost wholly of still photographs, to the teasing Last Year At Marienbad, (1961) or the split screen of Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (1966), cinema was in the middle of a creative free-for-all. It was hardly surprising to find the ever-subversive Luis Buñuel at large in such an atmosphere, filming The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) half a century after Un Chien Andalou.

New Hollywood

In response to the prospect of losing young audiences to television, the Hollywood that had once kept such a tight grip on its filmmakers now handed over a measure of control to a new breed of singular talents.

The results were American movies shot through with cynicism and irresolution. Some are best seen as historical documents, but others are enduring masterpieces. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation is a mystery of surveillance with a dazzlingly intricate use of sound, while his saga of family and crime, The Godfather, is an all-time classic that still holds audiences in its grip. as does The Godfather: Part II, the prequel that follows Vito Corleone from the Old World to the New.

For an era that began with Truffaut and Godard gleefully riffing on Hollywood tropes, it was fitting to close with a relentless crisscross of influence between Europe and the US: visions of Boris Karloff amid the Spanish Civil War in The Spirit of the Beehive; the relocation of German-born Douglas Sirk’s lush melodramas from Hollywood to 1970s Munich in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats The Soul; and Chinatown, a noir exposé of the black heart of southern California, directed by the Polish émigré Roman Polanski.

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Satire

DIRECTOR

Federico Fellini

WRITERS

Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Brunello Rondi, Pier Paolo Pasolini

STARS

Marcello Mastroianni, Anita Ekberg, Anouk Aimée, Yvonne Furneaux

BEFORE

1945 Fellini cowrites Rome, Open City, Roberto Rossellini’s gritty Nazi-occupation drama.

1958 Marcello Mastroianni gets his big break in the stylish crime-comedy Big Deal on Madonna Street.

AFTER

1963 Fellini’s autobiographical comedy-drama 8½ follows a director (played by Mastroianni) suffering from writer’s block.

In April 1953, the partially clad body of a young woman was discovered on a beach near Rome. Had Wilma Montesi accidentally drowned or committed suicide, or had she been murdered? The police investigated, and so did Italy’s rapacious media. Gossip and conspiracy theories snowballed into a national scandal as the corrupt, hedonistic underworld of postwar Rome was illuminated by the flash bulbs of the city’s paparazzi. Politicians, movie stars, gangsters, artists, prostitutes, fading aristocrats—they were living la dolce vita, “the sweet life,” a whirl of drugs, orgies, and general depravity that had spun tragically out of control.

La Dolce Vita became the title of Federico Fellini’s satire of this turbulent period in the history of his beloved Rome. The movie contains a veiled reference to the Montesi affair in its closing scene, when a group of characters emerge from a beach-house orgy to find a dead manta ray washed up on the shore, a metaphoric reference to Wilma Montesi. They gather around the corpse in the dawn light, the sea monster’s eye staring back accusingly at them. It’s a chilling image that is both grotesque and sad—the final entry in Fellini’s catalogue of lost souls.

"All art is autobiographical. The pearl is the oyster’s autobiography."

Federico Fellini

The Atlantic, 1965

The movie poster casts Marcello Mastroianni as a paparazzo in the shady underworld, searching for light in the form of his perfect Eve.

Seven sins

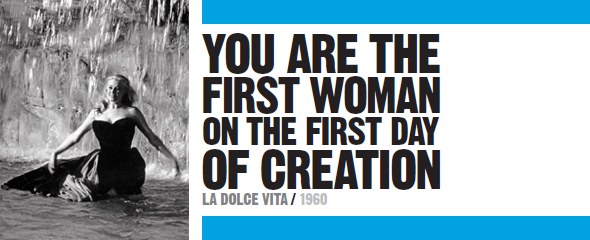

La Dolce Vita was released seven years after the death of Wilma Montesi. It takes place on the seven hills of Rome, its narrative divided into seven nights and seven dawns. If you look hard enough, you’ll also find that it contains the seven deadly sins and allusions to the biblical story of the seven days it took God to make the world. Religion is core to Fellini’s work. When the movie’s hero, a nocturnal journalist named Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni), falls for the beautiful movie star Sylvia (Anita Ekberg), he tells her, “You are the first woman on the first day of Creation. You are mother, sister, lover, friend, angel, devil, earth, home.”

It’s up to the viewer to decide on the significance of La Dolce Vita’s religious overtones and apparent obsession with the number seven. What is more certain is that the movie is concerned with the nature of men’s relationship with women. Marcello spends his nights on Via Veneto, 1950s Rome’s street of nightclubs, sidewalk cafés, and after-dark debauchery, searching for happiness in the shape of an idealized love. There are several contenders, including his suicidal fiancée, Emma (Yvonne Furneaux), and the mysterious Maddalena (Anouk Aimée). But it’s not until Ekberg’s Sylvia arrives in the city, amid a riot of adulation and publicity, that Marcello glimpses perfection. In the movie’s most celebrated scene, Sylvia wanders into the waters of the Trevi Fountain after a long, carnivalesque night on the town. She calls to Marcello to follow her in, and the viewer sees Sylvia through Marcello’s eyes: the ideal woman, unearthly in her radiance, a vision of light in the dark city. But then dawn arrives and the magical spell of nighttime is broken, just as Sylvia anoints Marcello’s head with water from the fountain. The next day Sylvia leaves Rome, and Marcello must begin his search again.

The chaos of Marcello’s night-wanderings is reflected in the movie’s meandering, episodic story structure. His adventures take him all over the city, from a field in which two children claim to have seen a vision of the Virgin Mary—the archetypal elusive, idealized woman—to the domestic bliss of Steiner’s house. Steiner (Alain Cuny) is Marcello’s best friend, and the epitome of all that Marcello envies: Steiner is stable, happily married with two perfect children, and enjoys a balance of materialistic comfort and intellectual fulfilment. When Marcello visits Steiner’s home, he ascends from the dark underworld of the streets, clubs, and basement bars, into a kind of heaven.

Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) is smitten with Sylvia, but they can only spend one night together.

“A man who agrees to live like this is a finished man, he’s nothing but a worm!”

Marcello / La Dolce Vita

La Dolce Vita takes place over seven days, nights, and dawns. While day appears to offer Marcello hope, night leads him into depravity, and dawn brings rude epiphanies.

FEDERICO FELLINI Director

Born in Rimini, Italy, in 1920, Federico Fellini moved to Rome when he was 19 years old. He went to study law, and stayed to make movies that would immortalize the city. His early adventures as a reporter and gossip columnist exposed him to the world of show business, and in 1944 he became the apprentice of famed director Roberto Rossellini. In the 1950s, Fellini made movies of his own, and established himself as one of Italy’s most controversial artists.

Fellini’s work combines baroque imagery with everyday city life, often depicting scenes of excess. He was fascinated with dreams and memory, and many of his later movies tipped into the realm of psychological fantasy.

Key movies

1952 The White Sheik

1954 La Strada

1960 La Dolce Vita

1963 8½

Illusion of happiness

But, just as Sylvia and the Virgin Mary turn out to be illusions, Steiner’s domestic happiness is also a lie, as Marcello discovers when Steiner tells him, “Don’t be like me. Salvation doesn’t lie within four walls.” That there is no comfort in either a sheltered, intellectual, domestic life nor the hedonistic “sweet life” is the existential conundrum Marcello wrestles with in the face of Steiner’s subsequent suicide. After an unspecified time lapse, we see Marcello at the beach house in Fiumicino, owned by his friend Riccardo, where the all-night party descends into mayhem. As morning approaches, he finds himself staggering across the beach, where the staring eye of the dead manta ray is waiting for him.

The final scene of La Dolce Vita contains a second allusion. The fisherman who hauls the ray out of the sea says the bloated, rotting leviathan has been dead “for three days.” In the Bible, this is the same period of time that Jesus spends in the tomb. La Dolce Vita is a carnival of Roman Catholic imagery and symbols, much of it controversial in its use. The opening sequence, in which a golden statue of Christ flies over an ancient Roman aqueduct, dangling benignly from a helicopter with Marcello following it in a second helicopter, caused outrage when the movie was first screened.

Although two Christ figures (the statue and the manta ray) bookend the narrative, they fail to offer hope or salvation to any of its characters. In fact, Fellini constantly connects religious myth with disillusionment. Marcello is looking for his Eve, the first woman on the first day of Creation, an angelic figure untainted by the corruptions of la dolce vita or any earthly experience. “I don’t believe in your aggressive, sticky, maternal love!” he tells Emma during their endlessly recurring fight. “This isn’t love,” he screams at her, “it’s brutalization!” And so whenever he dives back into the chaos of the Roman night, he knows that Eve doesn’t really exist; all he is doing is trying to forget what he knows.

Marcello is repeatedly drawn to Maddalena (Anouk Aimée), but his love for her cannot lead anywhere. She asks him to marry her, only to fall into the arms of another man moments later.

"In sum, it is an awesome picture, licentious in content but moral and vastly sophisticated in its attitude and what it says."

Bosley Crowther

New York Times, 1960

MARCELLO MASTROIANNI Actor

Following a brief period of theater work, Marcello Mastroianni became famous with a role in Big Deal on Madonna Street. He was Fellini’s only choice for the role of Marcello Rubini in La Dolce Vita. The studio had wanted Paul Newman, but Fellini fought to keep his friend, and the pair went on to make six more movies together. Mastroianni often played a version of the director in these movies.

A suave and darkly handsome figure, Mastroianni became closely associated with the glamour of Rome and its beautiful leading ladies, especially Sophia Loren (who shared the screen with him in 11 movies). He earned two Academy Award nominations during his career, one for the comedy Divorce Italian Style in 1961 and the other for A Special Day in 1977.

Key movies

1958 Big Deal on Madonna Street

1960 La Dolce Vita

1961 Divorce Italian Style

1963 8½

What else to watch: The Bicycle Thief (1948) ✵ L’Avventura (1960) ✵ Juliet of the Spirits (1965) ✵ Amarcord (1973) ✵ Cinema Paradiso (1988) ✵ Celebrity (1998) ✵ Lost in Translation (2003)