The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Historical drama

DIRECTOR

Sergei Eisenstein

WRITER

Nina Agadzhanova

STARS

Aleksandr Antonov, Vladimir Barsky, Grigori Aleksandrov

BEFORE

1925 Eisenstein’s first full-length feature, Strike, tells the story of a 1903 walkout in a Russian factory and the repression of the workers.

AFTER

1928 Eisenstein’s October (Ten Days That Shook the World) uses a documentary style to tell the story of the 1917 October Revolution.

1938 In a more restrictive political climate, Eisenstein retreats to distant history with Alexander Nevsky.

Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin was commissioned by the Soviet authorities to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the 1905 Revolution, when Russian sailors mutinied against their naval commanders and protested in the port of Odessa (now in Ukraine). The result was a movie that revolutionized cinema. Ninety years later, it is rare that an action movie does not owe it something.

The opening scenes are historically accurate. The cooks did take issue with the maggot-ridden meat, only to be told that it was fit for consumption. The crew’s spokesman, Quartermaster Grigory Vakulinchuk (Aleksandr Antonov), did call for a boycott and was shot. The crew did turn on their superior officers before hoisting a red flag and sailing to Odessa, where there had been ongoing civilian unrest. And Vakulinchuk’s body was put on display, with a note: “This is the body of Vakulinchuk, killed by the commander for telling the truth.”

When the sailors reach Odessa, however, Eisenstein’s movie veers into propaganda. While it is true that Tsar Nicholas II took action against the striking citizens of Odessa, this did not happen at the Odessa Steps. Now known as the Potemkin Stairs, they were then just the Boulevard Steps, or Giant Staircase. The director made full use of the 200 steps to show the tsarist troops advancing. The crowds’ celebration with the sailors is cut short by a title card that says simply, “And suddenly.” The scenes of carnage that follow have lost none of their power. Nobody is safe from the advancing troops, filmed from a low angle and often tightly cropped: for the director, only their rifles needed to be visible. The outraged sailors fire back with shells, before heading off to sea where they are joined in revolt by other sailors.

"View it in the same way that a group of artists might view and study a Rubens or a Raphael."

David O. Selznik

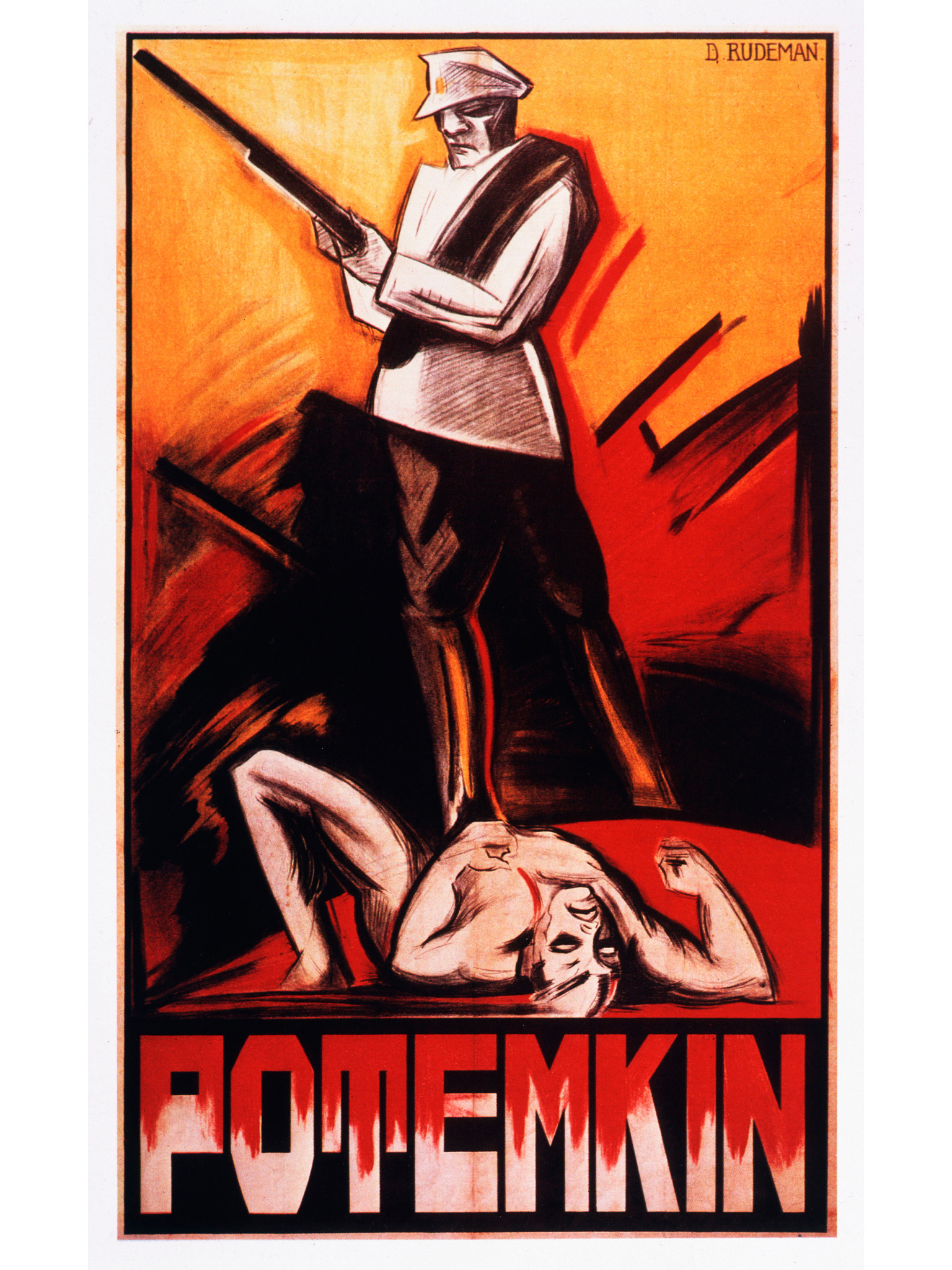

This was one of the first movie posters by Dutch designer Dolly Rudeman. It depicts a Cossack soldier with one of his victims at his feet. Its bold futurist style is typical of 1920s posters in Europe.

Montage and collision

As a history lesson, Battleship Potemkin took liberties, but factual accuracy was never Eisenstein’s concern. It was more important for him to pursue a new cinematic language, which he did by drawing on the experiments in montage pioneered by Soviet movie theorist Lev Kuleshov between 1910 and 1920. For Kuleshov, meaning lay not in individual shots but in the way that the human mind contextualizes them: for example, by using the same image of a man’s face and intercutting it with a bowl of soup, a coffin, and a woman, Kuleshov could conjure up images of hunger, grief, and desire. Eisenstein’s belief in montage—although he preferred to use images in “collision” with each other—can be shown by statistics alone: at under 80 minutes, Battleship Potemkin consists of 1,346 shots, when the average movie of the period usually contained around 600.

Manipulating emotions

Eisenstein’s approach to storytelling still seems radical today. Its juxtaposition of the epic and the intimate virtually rules out the possibility of engaging with the characters on a personal level, and in that way it is indeed perfectly communist. Even Vakulinchuk, the hero and martyr of the piece, is seen only as a symbol of humanity to be contrasted with the faceless tsarist troops. The most famous scene—a baby in a carriage tumbling down the steps—is the ideal symbol of the movie’s manipulative grip on our helpless emotions.

A carriage careers down the steps past and over the bodies of the dead and dying. The baby’s mother has been shot: as she fell, she nudged it forward, starting its headlong descent.

SERGEI EISENSTEIN Director

Born in 1898 in Latvia, Sergei Eisenstein started work as a director for theater company Proletkult in Moscow in 1920. His interest in visual theory led to the “Revolution Trilogy” of Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October. He was invited to Hollywood in 1930, but his projects there stalled. Back in the Soviet Union, he found that the political tide had turned against his “formalist” ideas, to more traditional storytelling. He died in 1948, leaving behind just eight finished movies.

Key movies

1925 Battleship Potemkin

1928 October

1938 Alexander Nevsky

What else to watch: Strike (1925) ✵ October (1928) ✵ Man With a Movie Camera (1929) ✵ The Untouchables (1987) ✵ JFK (1991)