The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Mystery drama

DIRECTOR

Orson Welles

WRITERS

Orson Welles, Herman J. Mankiewicz

STARS

Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore

BEFORE

1938 Welles directs a radio adaptation of H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, about an invasion from Mars. Its news-bulletin style is said to have caused some listeners to believe that it was real.

AFTER

1958 Welles’s noir thriller Touch of Evil tells a story of corruption in a Mexican border town.

1962 Welles makes a visually stunning adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial.

I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life,” says Charles Foster Kane, the towering press-baron protagonist of Citizen Kane. And yet the genius of this movie—cowritten, starring, and directed by Orson Welles at the age of just 25—is that it does just that: takes a single word that captures the origin and essence of the mercurial Kane, and teases the audience with it for nearly two hours, before offering an enigmatic clue to its meaning.

Shot in secrecy to preempt legal attempts to block production, and ambiguously billed as a love story, Welles braced himself for trouble upon its release. Kane’s character was not only based on a living person, but one who was extremely powerful.

Citizen Kane is a murder mystery without a murder, even though it famously opens with Kane, in old age, as a dying man. Starting his movie at the end is just the first of Welles’s many innovative temporal devices. The narrative then switches to a newsreel clip that recalls the life and deeds of the great Kane. It shows the building of his stately home, Xanadu, a sprawling mansion that he fills with art (“Enough for ten museums—the loot of the world”). It shows Kane’s influence spreading across the US and then across the world, as he stands on a balcony next to Adolf Hitler (cutting to a shot of Kane declaring, pompously, “You can take my word for it, there will be no war”). Next come the women in his life, and how an illicit affair cut short his political career. The audience is shown his rise, fall, and withdrawal from public life.

"Your faithful bystander reports that he has just seen a picture which he thinks must be the best picture he ever saw."

John O’Hara

Newsweek, 1941

The riddle of Rosebud

When the newsreel ends, its producer isn’t satisfied: he wants to know who Charles Foster Kane was, not what he did, and sends reporter Jerry Thompson (William Alland) to discover the meaning of the word Kane uttered with his last breath: “Rosebud.” At this point, Citizen Kane essentially becomes two movies. The framework is Kane’s life as recounted by his friends and enemies, as Thompson squares up to this extraordinary riddle wrapped in a larger-than-life enigma. But Welles also slyly offers the audience other scenes from Kane’s life in flashback, a technique that will finally allow him to reveal the truth that will elude Thompson and all the others.

A good deal of the movie’s artistic success can be attributed to Welles’s experience of working in theater. Citizen Kane is a movie that not only uses temporal devices in the narrative, but spatial ones, too, so that it can sometimes almost seem like a 3D movie. In a crucial early scene, Thompson discovers how Kane was born to a poor family who discovered gold on their land and, as part of a business deal, handed the boy over to a wealthy guardian. As the bargain is made in the foreground, we see the young Kane through the window, playing in the snow, oblivious. It is a simple perspective trick imported from theater, and it is used to capture the tragedy that befalls Kane. It is the moment in which the life he should have led ends.

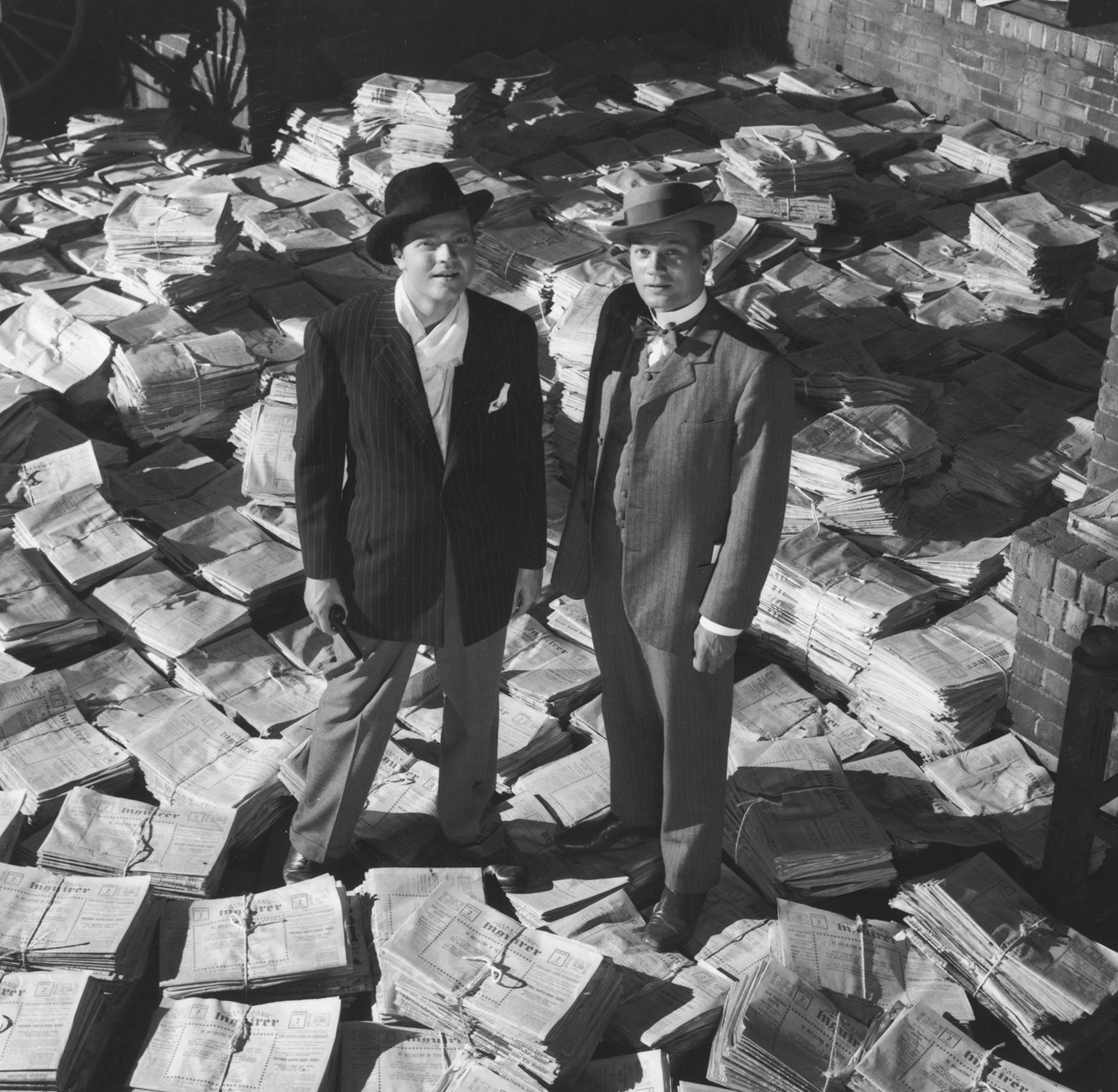

In happier days, Kane and Leland stand surrounded by copies of the Inquirer. Kane intends to use the paper to campaign for ordinary folk, a pledge that Leland will later throw back at him.

“Old age. It’s the only disease…that you don’t look forward to being cured of.”

Bernstein / Citizen Kane

Innovative shots

Welles and cameraman Gregg Toland employed such spatial devices throughout the movie, a feat achieved with deep-focus lenses and camera angles so low that Kane may appear, variously, as a titan and as a gangster. This in itself was a novelty, since prior to Citizen Kane filmmakers rarely used such upward shots, for the simple reason that few studios had ceilings due to the lighting and sound equipment. (“A big lie in order to get all those terrible lights up there,” said Welles.) Yet Welles took his camera so far down that, for a scene in which Kane talks with his friend Leland after losing his first election, a hole had to be dug in the concrete studio floor.

Toland’s input is a vital part of Citizen Kane’s legacy, since, although it would seal Welles’s status as one of America’s first auteur directors, this was very much a collaborative effort. Also vital was the risk Welles took with his cast and production team—for whom Citizen Kane launched their careers in movies. Many of the actors were unknown to audiences—they came from Welles’s Mercury Theatre group. His editor, Robert Wise, would soon begin a successful directing career of his own; and the score marked a debut for Bernard Herrmann, later to form an extensive creative partnership with Alfred Hitchcock. But more than anything, the movie’s brilliance is due to its script, which Welles cowrote with screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz. Although Mankiewicz’s exact contribution has been disputed, often by Welles, the movie does bear extensive traces of Mankiewicz’s satirical style: at one particularly loaded moment, having his affair discovered by his wife, Kane simply says, dryly, “I had no idea you had this flair for melodrama, Emily.”

Leland (Joseph Cotten) speaks at Kane’s political rally. Ultimately the campaign, and their friendship, will be derailed by Kane’s obsessive affair.

"The film’s style was made with the ease and boldness and resource of one who controls and is not controlled by his medium."

Dilys Powell

The Sunday Times, 1941

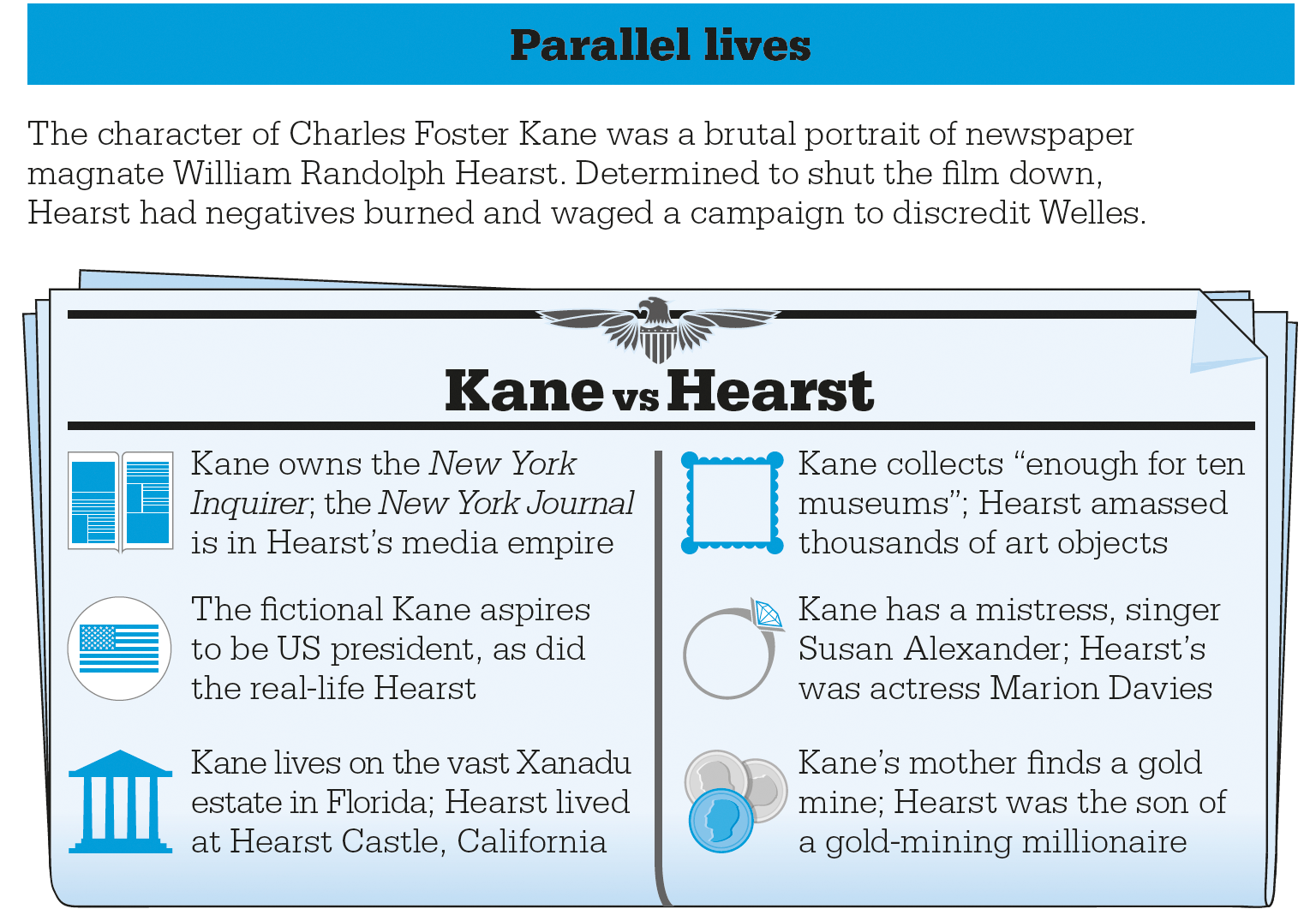

Parallels with Hearst

Despite the arguments over who wrote what, it is agreed that it was Mankiewicz who first came up with the idea for the movie. Having attained some success as a writer in the silent era, Mankiewicz became a sought-after script doctor, and it was in this capacity that he came to know the press tycoon William Randolph Hearst and his mistress, the movie actress Marion Davies. Although everyone denied it—including Hearst, who behaved with a very Kane-like determination to destroy the movie and its makers’ reputations—the parallels between Hearst and Kane were all too clear. It is a common fallacy that the movie flopped on release (it was the sixth-highest grossing movie of the year and nominated for nine Oscars), but a blanket ban by Hearst’s vast media empire ensured that its success was short-lived. Although it satirizes several cherished ideals, including the American dream (Kane sees no irony in being an autocratic capitalist who claims to fight for the common man), Citizen Kane does have sympathy for its subject. With Kane dead and Thompson unable to finish his quest, Welles’s camera takes viewers through the clutter of Xanadu, where Kane’s vast and gaudy art collection is being packed away.

Finally, the shot settles on the sled, named Rosebud, that Kane was playing with in the snow outside his parents’ shack. No one knows but us, and Kane, that this sled represents the key moment of his life: the moment he lost his innocence and happiness.

Welles’s eye for publicity was evident in the posters for the original release, which talked up the movie without giving anything away.

ORSON WELLES Director

Welles’s life mirrors that of Charles Foster Kane, in that he was taken in by a family friend, having lost both parents at 15. In 1934, he began working on radio plays and in 1937 founded the Mercury Theater—two things that would bring him great notoriety in 1938 when the company performed War of the Worlds as a live news broadcast. Welles was approached by RKO Studios in Hollywood, where he was given unheard of privileges for a new director, including the final cut for Citizen Kane. His next movie The Magnificent Ambersons, was butchered by RKO, the first of many creative quarrels that would plague his career. He died at 70 in 1985.

Key movies

1941 Citizen Kane

1942 The Magnificent Ambersons

1958 Touch of Evil

1962 The Trial

What else to watch: The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) ✵ The Lady from Shanghai (1947) ✵ The Third Man (1949) ✵ Touch of Evil (1958) ✵ The Trial (1962) ✵ Me and Orson Welles (2008)