The Movie Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained) (2016)

INTRODUCTION

Movies are so much a part of today’s culture that it is hard to imagine a time when they weren’t there at all. It’s hard, too, to appreciate the awe felt by the public of the 1890s at seeing moving pictures for the first time, as ghostly figures came to life before their eyes. From a 21st-century viewpoint, however, the real shock is how far those “movies” changed in the next three decades—quickly evolving into gorgeously vivid feature movies.

Magic on screen

For the early filmmakers, there were no masters to learn from. Some had a background in theater, others in photography. Either way, they were breaking new ground, and none more so than Georges Méliès. As soon as this sometime magician had begun entertaining the French public with movies, he looked for ways to make them more splendid and spectacular. In America, too, visionaries were at work. There, cinema thrived thanks to the likes of Edwin S. Porter, a former electrician who ended his 1903 feature The Great Train Robbery with a gunman turning toward the camera and appearing to fire at the audience.

Other filmmakers had grander plans. A few years later, Porter was approached by a fledgling playwright who hoped to sell him a script. Porter turned down the script, but hired the young man as an actor—and that same young man, the gifted and still controversial D. W. Griffith, later become a director himself, helping to father the modern blockbuster.

Movies as art

Although the pioneers clustered in France and America, it was in Germany that the movies first became art. In the aftermath of World War I, a country mired in political and economic chaos gave rise to a string of masterpieces whose influence still echoes today. The silent era was filled with some of the most glorious, pristine filmmaking that cinema would ever know: the works of Robert Wiene, F. W. Murnau, and Fritz Lang. Yet even then, it wasn’t just directors who deserved the credit—take the giant Karl Freund, a huge man with an equally vast knowledge of cameras, who would become a master cinematographer, strapping the camera to his body and setting it on bicycles to revolutionize how a movie could look.

Painters were also drawn to the screen, and in 1929, the famed Surrealist Salvador Dalí worked with a young movie fanatic named Luis Buñuel on the eternally strange Un Chien Andalou; Dalí then stepped away from movies, but Buñuel continued making iconoclastic movies into the 1970s. There were revolutionaries of the political kind, too. In the Soviet Union, cinema was embraced as the art form of the people. Movies became key to the global battle for hearts and minds.

Hollywood begins

Back in America, the cinematic hustlers became the first studio bosses of Hollywood. They built their businesses on stars such as Rudolph Valentino, Douglas Fairbanks, and Greta Garbo.

The biggest stars were clowns, and of all the wonders of the silent age, it is the comedies that most reliably delight today. In Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, Hollywood found two true geniuses who had honed their craft in American vaudeville and British music hall and now worked their magic on camera. Masters of mime, slapstick, and pathos, they could make audiences laugh just by looking at them. They were also meticulous filmmakers with a taste for innovation.

If one person defined the early movies, it was the phenomenally famous and endlessly ambitious Chaplin. By the end of this era, sound arrived—it was 1927 when Al Jolson declared in The Jazz Singer: “You ain’t heard nothing yet!” But Chaplin’s love for silent movies was such that he kept making them, and in 1931, with City Lights, he made one of the very greatest. By then, he had already helped the movies claim their rightful place, where they still are today—in the center of people’s lives.

"Charlie Chaplin and I would have a friendly contest: Who could do the feature film with the least subtitles?"

Buster Keaton

IN CONTEXT

GENRE

Science fiction, fantasy

DIRECTOR

Georges Méliès

WRITERS

Georges Méliès, from novels by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells (all uncredited)

STARS

Georges Méliès, Bleuette Bernon, François Lallement, Henri Delannoy

BEFORE

1896 Méliès’s short movie Le Manoir du Diable (The Devil’s Castle) is often credited as the first horror movie.

1899 Cinderella is the first of Méliès’s movies to use multiple scenes to tell a story.

AFTER

1904 Méliès adapts another Jules Verne story with Whirling the Worlds, a fantasy about a group of scientists who fly a steam train into the sun.

As its title suggests, the 12-minute-long movie A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune) is a fantastical account of a lunar expedition. A group of scientists meets, a huge gun is constructed, and astronauts are blasted to the moon, where they fall into the hands of the moon-dwelling Selenites. They are brought before the King of the Selenites, but manage to escape. They return to Earth, where a parade is held in their honor and an alien is put on display.

Magic tricks

Some pioneers of the cinema, such as the French Lumière Brothers, saw the new medium as a scientific breakthrough, a means of documenting reality. Frenchman Georges Méliès, the director of A Trip to the Moon, however, recognized it as a new way of performing magic tricks.

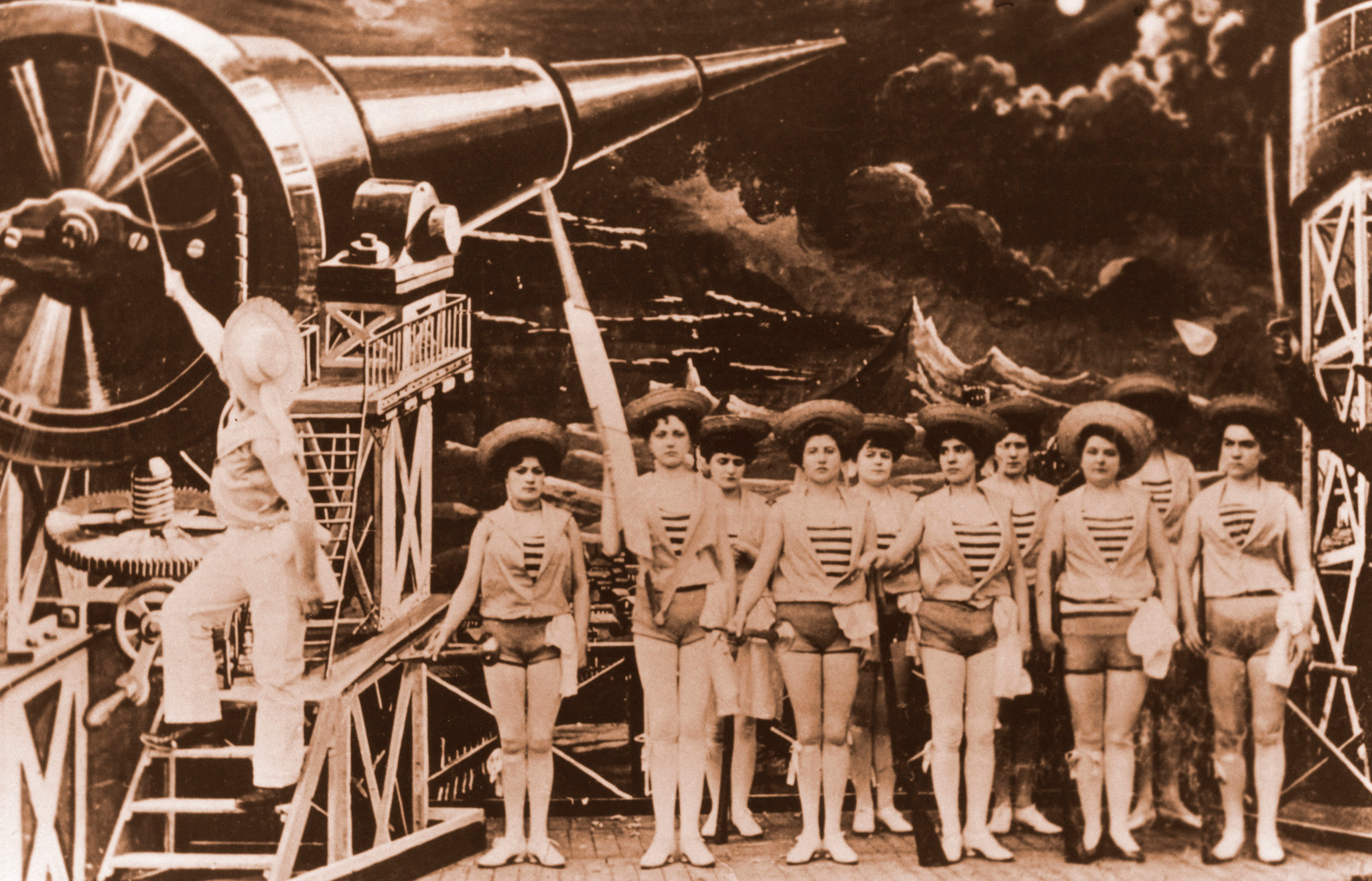

Méliès’s short movies were simply entertainments, created for the sensation seekers who roamed the boulevards of fin-de-siècle Paris. Filled with chorus girls, ghosts, and Mephistophelian devils, the movies started out as recordings of simple magic acts and evolved into fanciful stories realized through innovative and audacious camera trickery—cinema’s fledgling special effects. By 1902, Méliès was ready to pull off his biggest illusion: to take his audiences to the moon and back.

Chorus girls line up to fire the Monster Gun that will blast a spaceship to the moon. Méliès’s overblown theatrical style keeps the action more absurd than heroic.

Sci-fi and satire

A Trip to the Moon was the first movie to be inspired by the popular “scientific romances” of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, and is widely acknowledged as the world’s first science-fiction movie. But while it is true that Méliès conjured up the basic iconography of sci-fi cinema—the sleek rocket ship, the moon hurtling toward the camera, and the little green men—the director did not set out to invent a genre. His aim was to present a mischievous satire of Victorian values, a boisterous comedy lampooning the reckless industrial revolutionaries of Western Europe.

In Méliès’s hands, men of science are destructive fools. Led by Professor Barbenfouillis (played by Méliès himself), they squabble and jump up and down like unruly children, and when they land on the lunar surface, their rocket stabs the Man in the Moon in his eye. They cause chaos in the kingdom of the Selenites—whom they treat as mindless savages—and they only make it home by accident. A statue of Barbenfouillis appears in the final scene—a caricature of a pompous old man, resembling one of Méliès’s political cartoons. Its inscription reads “Labor omnia vincit” (Work conquers all), which, in light of the chaos that has preceded it, takes on a decidedly ironic tone.

When they reach the moon, the scientists discover a strange land. Their arrogant attitude toward the moon people has led the movie to be seen as an anti-imperialist satire.

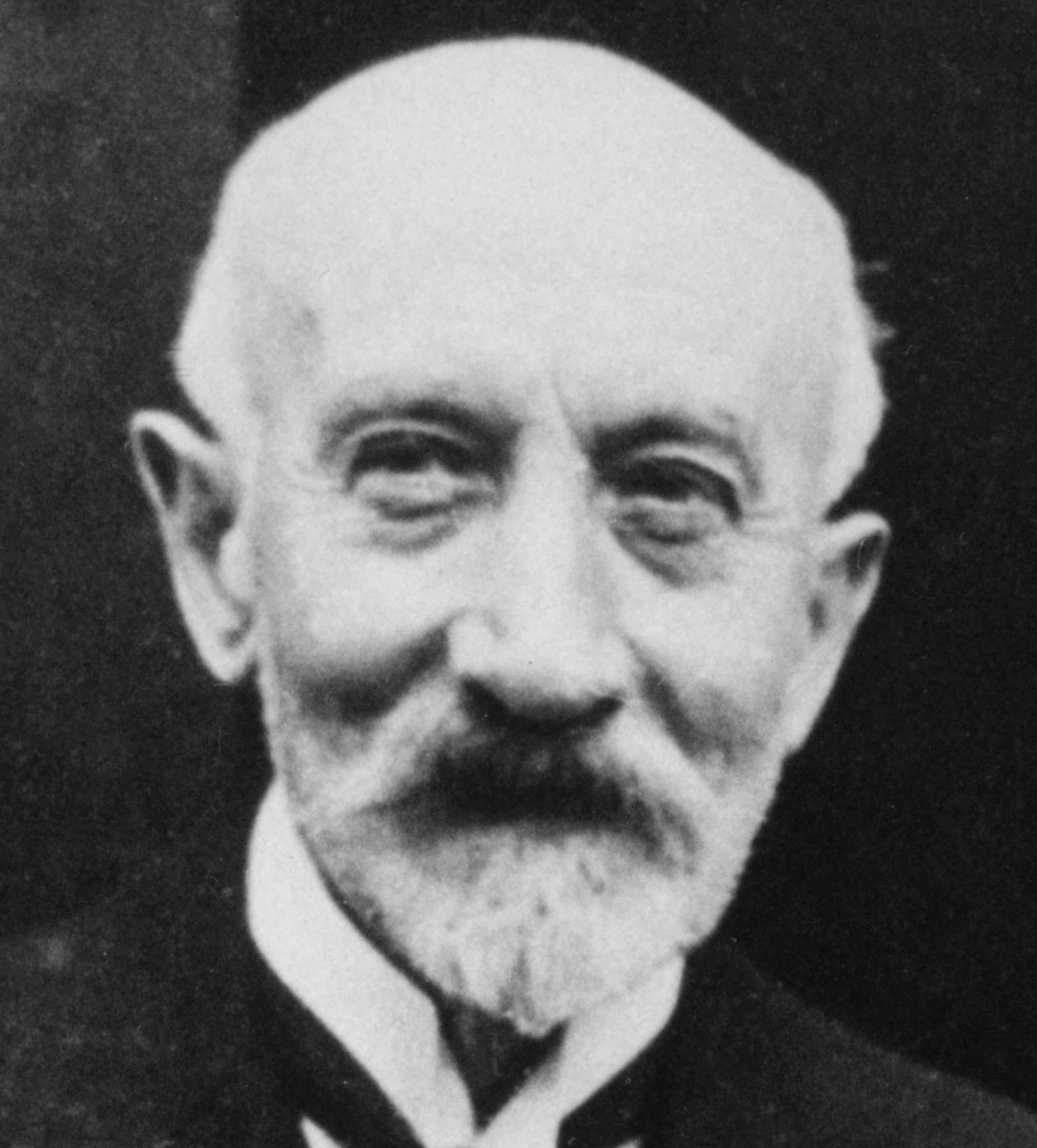

GEORGES MÉLIÈS Director

Méliès’s early short movies experimented with the theatrical techniques and special effects he had mastered as a stage magician. He used the camera to make people and objects disappear, reappear, or transform completely, and devised countless technical innovations. Méliès wrote, directed, and starred in more than 500 motion pictures, pioneering the genres of science fiction, horror, and suspense.

Key movies

1896 The Devil’s Castle

1902 A Trip to the Moon

1904 Whirling the Worlds

1912 The Conquest of the Pole

What else to watch: The Man with the Rubber Head (1901) ✵ A Trip to Mars (1910) ✵ Metropolis (1927) ✵ The Invisible Man (1933) ✵ First Men in the Moon (1964) ✵ Hugo (2011)