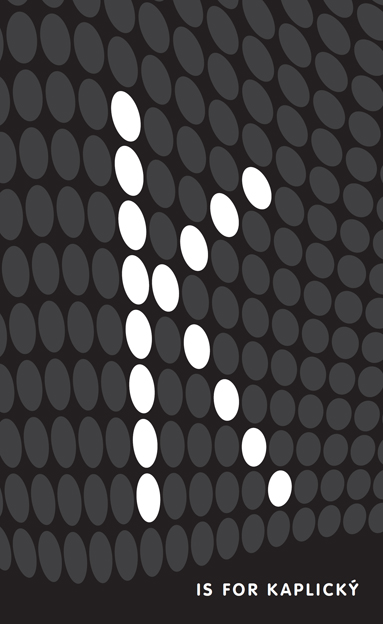

B is for Bauhaus, Y is for YouTube: Designing the Modern World from A to Z (2015)

When you are writing about architecture for a living, you feel a certain obligation to put what little money you have where your pen is. And so it was that I asked Jan Kaplický to remodel a flat inside a white-stucco terraced tenement in London’s Maida Vale for me. I was at the Sunday Times; he had just been made redundant by Norman Foster, who was going through one of his periodic downturns.

Kaplický and I had talked every so often for years, and it was clear to me that he was an architect like no other. He was born in Czechoslovakia, and had been educated behind the Iron Curtain. But what he was fascinated by was the future. He loved the idea of designing robotic spacestation buildings, demountable houses for helicopter pilots, and nose-cone shelters that could be buried on a beach or a mountaintop. I wasn’t expecting to get anything like that. But there was always something new that he was becoming enthusiastic about.

Kaplický was once asked to choose an artefact to be photographed with from an exhibition about tools at the Design Museum. He picked a Bren gun, designed in Brno, in what is now the Czech Republic, and made in Enfield in England. He was always looking for ways to reconcile the two worlds in which he lived. In Britain, he talked to me about Tatra limousines, the curiously reptilian Czech ancestors of the Volkswagen, the Villa Müller in Prague, designed by Adolf Loos, Czechoslovak military fortifications from the Second World War, and showed me the pictures that he brought with him of the handful of projects that he had built before he left Prague in 1968, when he fled the arrival of Soviet tanks. These were designs that would be startling in their freshness in any context. In what we thought we knew of life in the countries of the Warsaw Pact, they were extraordinary.

Kaplický lived a life fractured by the tragedies of the twentieth century. He was a baby when Czechoslovakia fell to the invasion of Hitler’s army and the young republic’s brave experiment in modernity was extinguished. And he was a child when Czechoslovak democracy was destroyed once more by the Soviet Union in 1948. By 1968, just as he was beginning to make his way as an independent architect, the Soviet Union’s tanks arrived in Wenceslas Square.

He had already been to America by this time. He had even seen the work of Charles Eames and Buckminster Fuller at first hand, albeit in Russia. Kaplický had seen the American National Exhibition in Moscow, designed by George Nelson with an installation by Charles and Ray Eames, during which Khrushchev had the famous kitchen debate with Richard Nixon. Kaplický made his way to London in 1968, but not before he had painted, in careful Cyrillic, a sign on a wall at the National Museum in Prague, inviting the Russian neighbours to go back to where they had come from, and checking with his mother that he had got the grammar right.

The first time that I saw the inside of Loos’s Villa Müller was for Jan’s funeral. He died the day that his daughter, Johanka, was born in Prague. A few days later, his family and a few friends gathered to say goodbye to him inside the villa. He had been married there and, sixty years earlier, he had played with the Müller children in the villa’s garden when he was growing up in Prague in the 1940s.

Kaplický was a Czech, and Loos was a German-speaking Bohemian. But in terms of their architectural output and general demeanour they have a certain amount in common. They were both polemicists, even if Loos believed that it was his duty to celebrate the sober, and the appropriate, and Kaplický was convinced that architecture that was not, in some sense, shocking or abrasive or outrageously sensuous was not worth thinking about.

London in the 1960s put Kaplický at the centre of an architectural world which he had only previously glimpsed through a keyhole of smuggled copies of Vogue and Life. Once he got there, he had a habit of being in the right place at the right time. He is in the group photographs of the Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers team that won the competition to build the Pompidou Centre in Paris. He went on to work for Norman Foster, on the early stages of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank.

He had a flat that was decorated with a photographic image of a hamburger that took up a whole wall, and an aluminium dining table that was full of holes and looked as if it had been borrowed from a Wellington bomber.

But Kaplický was living in another world, all this time. He was living in the world as it ought to be rather than the world as it is in reality, a world in which architecture was not the messy, muddy business that it actually is but in which he could design robot-built orbiting space stations, in which emergency shelters could be helicoptered into position slung from beneath the belly of a Chinook. A vision that he could only sustain by an unquenchable optimism that he could take the rest of us with him into a one-piece Neoprene-lined solar-powered rocket ride to the future; an optimism that sometimes he could not understand why we were conspiring to stop him from sharing with us.

With his friend David Nixon he started Future Systems, a name that suggests a corporation staffed by hundreds. It was sustained mainly by Kaplický’s determination, and the exquisitely beautiful drawings that he made. Elegant ink lines that recall, perhaps, the precision of his mother’s work as an illustrator.

Future Systems became more than a dream when Kaplický set up his own studio. Job One was my flat, a spaceship trapped and tethered inside a nineteenth-century London terraced house. He borrowed builders from his fellow Czech exile the architect Eva Jiřičná to make it happen. He created a series of aluminium-skinned platforms that stopped short of the walls, and what he called a culinary workstation - a T-shaped kitchen unit with a fibreglass top. If you put anything hot on the fibreglass, you risked a domestic version of the China syndrome.

Kaplický was able to turn some of his constant stream of ideas into physical reality. Others stayed as dreams that inspired others, among which were the design for the National Library of France in Paris, a glass canyon split by a footbridge across the Seine, and a brilliant scheme for the Parthenon Museum in Athens.

Finally there were big things to build with Amanda Levete: his department store for Selfridges in Birmingham, the press box at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London. And then he won a competition to design the National Library in Prague and was also asked to design a concert hall in České Budějovice; both were projects that attracted a great deal of attention, but were unrealized.

His architecture was always a celebration of beauty. He found aesthetic inspiration in the wing of an aircraft, the curved blade of a helicopter rotor, in the legs of a lunar lander, in a metal dress by Paco Rabanne, in the curves of a human body, and they are all there in his architecture, showing us another way to understand the world around us.