Apollo - Fritz Graf (2009)

KEY THEMES

3. ORACULAR APOLLO

As soon as he is born, Apollo stakes out the areas of his responsibility - “the lyre, and the curving bow,” and “to proclaim the unerring counsel of Zeus” (Hymn to Apollo 131f.), that is mousik![]() , shooting, and divination. We talked about the former two in the preceding chapters; this chapter is devoted to the third item. Divination - rituals to acquire “the foresight and knowledge of the future,” in Cicero’s somewhat narrow definition (On Divination 1.1) - played no great role in the Homeric world. Certainly, there were the seers: Calchas who accompanied the army in the Iliad, Tiresias whose ghost Odysseus consulted in the Underworld, and the Trojan Helenus who claimed to “hear the voice of the timeless gods” (Il. 7.53). And there were two main oracles, that of Zeus in Dodona “where thy prophets live, the Selloi, bare foot and sleeping on bare earth” (Il. 16.234), and Apollo’s oracle in Delphi where Agamemnon asked for advice about the outcome of the expedition to Troy (Od. 8.80). But neither Homeric poem seems aware of the important and often decisive role oracles played in the ancient world, from the Archaic Age of the Greeks to the end of pagan antiquity.

, shooting, and divination. We talked about the former two in the preceding chapters; this chapter is devoted to the third item. Divination - rituals to acquire “the foresight and knowledge of the future,” in Cicero’s somewhat narrow definition (On Divination 1.1) - played no great role in the Homeric world. Certainly, there were the seers: Calchas who accompanied the army in the Iliad, Tiresias whose ghost Odysseus consulted in the Underworld, and the Trojan Helenus who claimed to “hear the voice of the timeless gods” (Il. 7.53). And there were two main oracles, that of Zeus in Dodona “where thy prophets live, the Selloi, bare foot and sleeping on bare earth” (Il. 16.234), and Apollo’s oracle in Delphi where Agamemnon asked for advice about the outcome of the expedition to Troy (Od. 8.80). But neither Homeric poem seems aware of the important and often decisive role oracles played in the ancient world, from the Archaic Age of the Greeks to the end of pagan antiquity.

Divination was as much concerned with the present as with the future: most of the time, it was a present crisis more often than a future undertaking that led people to use divination. Like the members of most societies around the globe, Greeks or Romans could choose between several different ways of seeking divine advice about their problems. On the one hand, there were long-established institutions that offered divinatory services through ritual means; most of them belonged to Apollo. In some cases, the client would directly meet with the divinity, usually in a dream. After specific rituals that prepared him for contact with the divine, he would spend a night in the sanctuary, in what was often called the “sleeping room,” enkoimeterion; if the need arose, temple-priests would help to interpret the dream in the morning. This method, called “incubation” after the Latin for “to sleep in,” incubare, was widely practiced in the healing sanctuaries of Apollo’s son Asclepius, and it survived in Christian times when local saints began to replace the pagan healing divinities. Contact also could be indirect and rely on a medium who connected the human petitioner with the divinity, such as the famous Pythia in Delphi. Such a human medium was thought to have access to the god’s mind because she or he was possessed by the divinity. Spirit-possession as a way of communication with the supernatural world is an almost global phenomenon, although the specific forms and explanations vary from culture to culture. Sometimes, however, the communication relied solely on a set of oracular texts, inscribed on lots or on a chart; the petitioner drew a lot or threw one or several dice in order to determine which answer would be his. Sometimes, a human medium was added to this, such as the boy who, in the oracle of Fortuna Primigenia in Roman Praeneste, modern Palestrina, drew the lot for the petitioner. Children were thought to have an easier access to the divinity, and they also acted as medium in many private oracular cults in antiquity.

Besides these institutional oracles, there were the “free-lancers.” Professional seers inspected the entrails, especially the livers, of sacrificial animals, interpreted the flight of birds, or knew how to perform divination with a bowl of water or a mirror or by yet another of the many methods of private divination we hear about in antiquity. Oracle-sellers (chresmologoi) sold answers from bookish collections of texts that had been uttered, as they claimed, by famous inspired prophets, such as the Sibyl. Interpreters of dreams counseled people whose dreams seemed to predict some future event, and astrologers, in growing number through the centuries, offered the services of their discipline that was riding on the tenuous borderline between science and religion. Sometimes, these free-lancers were quite respectable: they served as seers with the commanders of regular armies or of mercenary groups, or advised kings and emperors. Often enough, however, they were on the margins of society, foreigners traveling from city to city, selling their services to whoever was willing to pay for them, and complementing these divinatory services with other useful rituals, such as initiations into mystery cults that promised a better life after death, or spells that put one’s enemy out of action, attracted a desired person, or helped one’s favorite charioteer win the race.

In cognitive terms, divination exploits the human need to make sense of as many data as possible that are constantly fed into our brains. This ability to make better sense of the world than our animal competitors gave humans the cutting evolutionary edge. Recently, scholars have begun to explain religion in the same terms. To put it somewhat simplistically: to understand otherwise inexplicable (and therefore disturbing and frightening) data with which the human brain must deal, we assume that superhuman agents intervene in our lives. These divine agents act and react just like we do, but they are stronger, wiser, and better than we are. This theory explains why what to our modern rationality are random phenomena were understood as signs in ancient divination - mostly opaque signs that needed further interpretation but that certainly were not random. The shape of a sheep’s liver, the flight of birds, a chance uttering overheard in a critical situation, the constellation of certain planets at a given time, or the working of the brain during sleep were all taken as signs with which a divine agent announced future events or answered anxious questions in a crisis. When divination did not focus on random natural events, it created them in a ritual process. Throwing dice, drawing lots (helped by naive children or irrational animals), falling into a trance, viewing the chance patterns made by oil on a surface of water were randomizing devices that opened up a crack in the rational causality of daily life; through it the hand or voice of a superhuman being signalled an answer to the more or less pressing question a human might put before it.

APOLLO’S DIVINATION

Nothing of this was necessarily connected with Apollo; he was not the only oracular divinity in the ancient world. If one assumed that gods knew more than humans, then any divinity could reveal the future; the same was true for heroic seers, and perhaps even for all dead ancestors. Zeus was not only consulted in Dodona but also in his sanctuary at Olympia and, in the guise of the Egyptian god Ammon, in his oasis sanctuary of Siwa in Northeastern Egypt. Ammon became famous among the Greeks when he greeted the visiting Alexander as his own son - hence the ram’s horns on coins of Alexander, the ram being sacred to Ammon. Hermes presided over oracles that were guided by chance, such as those relying on dice or a chance utterance by an unrelated passer-by. The Boeotian god or hero Trophonios received visitors under the earth; they arrived after a harrowing Underworld journey. The hero Calchas sent prophetic dreams to whoever slept on the hide of a sacrificial ram in his Southern Italian cave sanctuary.

But these cases pale in number, quality, and impact before the role Apollo played in divination. The god himself was well aware of it. When, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, the new-born trickster Hermes tries to blackmail his older brother into granting him the gift of divination, Apollo flatly refuses: “It is divinely decreed that neither you yourself nor another immortal may learn it. Only the mind of Zeus knows the future, and I in pledge have agreed and sworn a mighty oath that I alone of the immortal gods shall know the shrewd-minded counsel of Zeus” (v. 533-538). Prophecy is Apollo’s, and Apollo’s alone. This became more and more pronounced over the course of time. In the second or third century CE, someone asked Apollon in Didyma why so many oracles in the past were inspired either by sacred springs or by vapors rising from the earth but had now disappeared. The god himself answered:

Wide Earth herself took some oracles back into her underground bosom; others were destroyed by long-lasting Time. By now, there are left under Helios who sends light to the humans only the divine water in the valley of Didyma, and the one of Pytho under the high peaks of Parnassus, and the spring in Clarus, a narrow opening for a prophesying voice.

(Porphyry, Fragment 322 F.)

Only the three major Apolline oracular shrines, Didyma, Delphi and Clarus, remained functional, out of a much larger number in the past.

But already long before this date, almost all Greek oracular sites that had an international reputation belonged to Apollo, with the sole exceptions of Zeus’ oracles in Dodona and, later, Siwa in Egypt. And there was a host of minor oracular shrines of Apollo throughout the Greek world, sometimes known to us only through the text of an ancient author or the chance-find of an inscription. A single inscription provides the evidence that the sanctuary of Apollo in the beautiful sacred grove at Gryneion in the Troas functioned as an oracle in late Hellenistic times, and a single text tells us of an Apolline oracle in Hierakome (“Sacred Village”) in the Maeander valley: “There is a venerable sanctuary of Apollo and an oracle; the prophets are said to give responses in poetry of some elegance” (Livy 38.43, in an aside when describing a military expedition in the region). Minor oracular deities, such as the Boeotian god Ptoios, were identified with Apollo, as were indigenous Anatolian deities that had oracular cults. Even the dream healer Asclepius often operated in the shadow of his father Apollo: in several sanctuaries throughout the ancient world, Asclepius’ cult was later added to an old cult of Apollo.

This dominant role is not easy to explain. After all, it is not Apollo whose plans and designs make the world function, but Zeus. The Greeks could rationalize this by saying that Apollo had access to Zeus’ thoughts and plans as his favorite son, as does an oracle in Herodotus (7.141), or Apollo himself when he explains to his little brother Hermes why Hermes could not take over his brother’s divinatory powers. But some Greeks at least were not so sure that Apollo simply proclaimed Zeus’ counsel. One Hegesipolis first consulted the oracle of Zeus at Olympia, and then went to Delphi and asked Apollo “whether the son was of the same opinion as the father.” Aristotle, who tells the story (Rhetorics 2.23 p. 1398 b 34), is silent about Apollo’s reaction. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, historians explained Apollo’s role as an oracular god from his role as god of music and poetry, and constructed an impressive tribal past for it. “The god of Delphi, in fact, possesses all the attributes of the medicine-man, song, divination, healing, the unseen darts which strike down his opponents, and even the wand of laurel,” as one scholar phrased it. Nowadays, medicine-men or, as they were called in more recent times, shamans, have lost some of their lustre as an explanatory paradigm in Greek religion (as we saw in the last chapter). Rather, most oracular shrines were situated outside the city and the outlying farmland in what the Greeks called escháti![]() : it was in the wilderness, outside the space of civilized human activity, where humans were most likely to meet a god. One area of Apollo’s activity is this wilderness, as it is his twin sister’s, Artemis, whom scholars have called “Mistress of (wild) animals,” Pótnia therôn, and “Lady of the Wilderness.” Here, Apollo hunted game and chased nymphs such as Daphne, the daughter of a river-god who escaped his wooing by being changed into the laurel (daphn

: it was in the wilderness, outside the space of civilized human activity, where humans were most likely to meet a god. One area of Apollo’s activity is this wilderness, as it is his twin sister’s, Artemis, whom scholars have called “Mistress of (wild) animals,” Pótnia therôn, and “Lady of the Wilderness.” Here, Apollo hunted game and chased nymphs such as Daphne, the daughter of a river-god who escaped his wooing by being changed into the laurel (daphn![]() ), Apollo’s sacred tree. Here too, he presided over the training of the young city warriors, the ephebes. Many myths talk about the isolation of Apollo’s oracular shrines. The Cretans whom Apollo abducted to Delphi to become his priests were dismayed and shocked by the loneliness of the barren mountain he had moved them to. The foundation legend of the Didymaean sanctuary tells how Apollo seduced young Branchus “in the sacred wood” near Miletus (Callimachus, Fragment 229): Branchus was rewarded with the gift of prophecy and the “sacred staff of the god,” and he became the ancestor of the Branchidae, the clan from which Didymaean prophets came in the Archaic Age. The Asklepieion of Epidauros was founded at the spot in the woods where the future healing hero was born, at the bottom of a hill on whose top Apollo had a lonely peak sanctuary.

), Apollo’s sacred tree. Here too, he presided over the training of the young city warriors, the ephebes. Many myths talk about the isolation of Apollo’s oracular shrines. The Cretans whom Apollo abducted to Delphi to become his priests were dismayed and shocked by the loneliness of the barren mountain he had moved them to. The foundation legend of the Didymaean sanctuary tells how Apollo seduced young Branchus “in the sacred wood” near Miletus (Callimachus, Fragment 229): Branchus was rewarded with the gift of prophecy and the “sacred staff of the god,” and he became the ancestor of the Branchidae, the clan from which Didymaean prophets came in the Archaic Age. The Asklepieion of Epidauros was founded at the spot in the woods where the future healing hero was born, at the bottom of a hill on whose top Apollo had a lonely peak sanctuary.

THE HISTORY OF THE THREE MAJOR ORACLES OF APOLLO

Divination was a serious matter, from the peasant asking for advice about whether he should take up sheep-farming to the king consulting the god about matters of state. According to a story told by Herodotus (1.46-53), Croesus, the rich and powerful ruler of Lydia in Asia Minor in the sixth century BCE, went about the process with more than customary care - after all, he was planning an attack on the Persian Empire, the greatest power of his time. Thus, he first tested the most prominent oracles, those of Apollo in Delphi, Didyma, and little-known in Abae in Phocis, of Zeus in Dodona, and the Egyptian Zeus Ammon in his oasis in the Libyan desert, of Trophonios in Boetian Lebadeia, and of the seer hero Amphiaraus in Oropus in the borderland between Attica and Boeotia. He asked them all to tell him what he was planning at that very moment - but only the Pythia in Delphi and Amphiaraus in Oropus answered correctly: the king intended to cook a turtle and some lamb in an iron pot with an iron lid. Elated by this success, he sent immense sacrifices and gifts to Delphi, and he asked the god the second, vital question: should he attack the Persian king? The god gave the famously ambiguous answer: “When Croesus goes beyond the Halys, he will destroy a large empire” - his own, as it turned out, and not the Persians’, as Croesus had assumed.

Fame and decline of Delphi

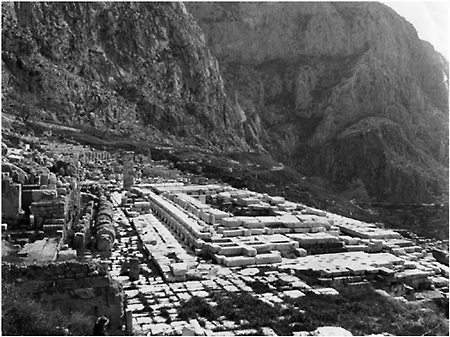

Even though Herodotus saw Croesus’ fabulous dedications in Delphi, the story might be an invention, but it highlights the fame of Delphi in the Archaic Age. The antiquity of the Delphic sanctuary was already being debated in antiquity. Myth made Apollo its third or fourth oracular god, after Earth (Gaia), Themis, and perhaps Phoib![]() (whoever she may be): this may date the foundation of the oracle before the reign of Zeus who was the lover of Themis. Such a mythical date does not reflect any actual history. There are no traces of a Bronze Age antecedent for the Iron Age sanctuary: Delphi must have been founded in the early Iron Age, at some time between 900 and 700 BCE. But it soon made a deep impact on the Greek world, as already Homer shows, and was regarded as the major Greek oracle sanctuary of the Archaic and Classical Ages. Its early architectural splendor impressed the Greeks. Homer’s audience must have admired the stone temple (the “stone threshold”) of Delphi, an unusual sight anywhere in Geometric Greece, and even more so high up in these lonely mountains, far away from civilization: no wonder Greeks sometimes thought that Apollo was his own architect and builder. During the Archaic Age, this lone stone temple developed into the bustling sacred complex that we still can see today, even in its ruined state. A wide and curving road lead through a forest of statues and past dazzling buildings (the marble treasuries which the most powerful Greek cities vied with each other to build) up to the impressive temple on its terrace, with a monumental altar in front (figure 4). And if one looked at the landscape while walking up towards the temple, one could see the mountain peaks of Parnassus towering above the sanctuary; one could see the deep valley and the far sea below, with a narrow, steep and winding road that lead up from a small harbor. These vistas brought home once again what Apollo’s civilizing force could achieve in the wilderness that was early Greece, as soon as one was outside its small cities. All this splendor resulted from Delphi’s central role in Archaic Greek political and religious life. The Delphic god approved of most colonial ventures around the Mediterranean. He sanctioned laws such as the Spartan constitution, the so-called “Rethra,” or the complex regulations of ritual purity for the colony Cyrene that we still possess; he legitimated changes in the constitution, such as the democratic revolution which Cleisthenes imposed upon Athens. He advised the Greeks on matters small and large, on how to be saved from the Persians as well as who should be honored with public dining in the city hall. And his advice was central to the denouement of many mythical narratives, not the least those put on the Athenian stage, such as the story of the Theban king Oedipus or of the Athenian king Aegeus and his wish for a son. So it does not surprise

(whoever she may be): this may date the foundation of the oracle before the reign of Zeus who was the lover of Themis. Such a mythical date does not reflect any actual history. There are no traces of a Bronze Age antecedent for the Iron Age sanctuary: Delphi must have been founded in the early Iron Age, at some time between 900 and 700 BCE. But it soon made a deep impact on the Greek world, as already Homer shows, and was regarded as the major Greek oracle sanctuary of the Archaic and Classical Ages. Its early architectural splendor impressed the Greeks. Homer’s audience must have admired the stone temple (the “stone threshold”) of Delphi, an unusual sight anywhere in Geometric Greece, and even more so high up in these lonely mountains, far away from civilization: no wonder Greeks sometimes thought that Apollo was his own architect and builder. During the Archaic Age, this lone stone temple developed into the bustling sacred complex that we still can see today, even in its ruined state. A wide and curving road lead through a forest of statues and past dazzling buildings (the marble treasuries which the most powerful Greek cities vied with each other to build) up to the impressive temple on its terrace, with a monumental altar in front (figure 4). And if one looked at the landscape while walking up towards the temple, one could see the mountain peaks of Parnassus towering above the sanctuary; one could see the deep valley and the far sea below, with a narrow, steep and winding road that lead up from a small harbor. These vistas brought home once again what Apollo’s civilizing force could achieve in the wilderness that was early Greece, as soon as one was outside its small cities. All this splendor resulted from Delphi’s central role in Archaic Greek political and religious life. The Delphic god approved of most colonial ventures around the Mediterranean. He sanctioned laws such as the Spartan constitution, the so-called “Rethra,” or the complex regulations of ritual purity for the colony Cyrene that we still possess; he legitimated changes in the constitution, such as the democratic revolution which Cleisthenes imposed upon Athens. He advised the Greeks on matters small and large, on how to be saved from the Persians as well as who should be honored with public dining in the city hall. And his advice was central to the denouement of many mythical narratives, not the least those put on the Athenian stage, such as the story of the Theban king Oedipus or of the Athenian king Aegeus and his wish for a son. So it does not surprise

Figure 4 Temple of Apollo in Delphi. View from the west. Copyright Alinari/Art Resource, NY.

that many grateful cities, kings, and aristocrats sent splendid gifts to Delphi and instituted sacrifices or festivals to Apollo Pythios at home; these gifts displayed the generosity and wealth of their donors to the international crowd that frequented the sanctuary. The Pythian Games, Delphi’s athletic and musical contest, were among the four most prestigious contests in Archaic and Classical Greece, almost on a par with the Olympic Games. And even though the oracle was suspected to side with the Persians when they attacked Greece in 490 and again in 480 BCE, after the Persian Wars this was conveniently forgotten; Delphi’s glory and credibility were quickly restored. In Hellenistic times, the oracle advised the senate of Rome, as it had advised the king of Lydia centuries earlier. Its fame was so great throughout the Mediterranean that even pirates heeded it: when the Romans sent a golden mixing bowl to Delphi, to thank the god for helping them conquer Veji in 395 BCE, pirates from the island of Lipari intercepted the ship but let it go when they learned about the addressee of the cargo (Livy 5.28). A lasting moment of glory came in 278 BCE, when a snowstorm or, as pious legends had it, the god himself drove away a marauding army of Gauls who had pushed south from the Balkans and were attracted by the gold hoarded in the sanctuary. The Delphians seized this as an occasion for self-propaganda, instituted a new festival and new games, the Soteria, “Salvation Day,” and sent out invitations to all Greek cities to participate.

The decline of Delphi began in 88 BCE. The Greeks let King Mithridates of Pontus, a minor local ruler in the southeastern corner of the Black Sea, seduce them into a misguided revolt against the oppressive rule of Rome; in Ephesus alone, a resentful mob killed 80,000 Italians. Rome’s bloody and destructive revenge led to sharp economic decline throughout Greece and Asia Minor.

When traveling back from Asia Minor, I sailed past Aegina towards Megara, (a friend of Cicero wrote in 45 BCE) and I began to look around. Aegina was behind me, Megara in front of me, to the right was the Piraeus, to the left Corinth: all these places were once flourishing, but now you see only ruins lying in the fields.

(Servius Sulpicius, in Cicero, Letters to his Friends 4.5.4).

This decline affected Delphi, as it affected other oracles all over the Greek world that, after all, lived off the fees (“gifts”) of their grateful clients. A century later still, Plutarch of Chaeroneia (about 46-120 CE), a philosopher, historian, and a Delphic priest, felt compelled to write a dialogue on The Decline of Oracles in which he pondered the reason for the loss of influence and prestige Delphi and many other oracles suffered. In Plutarch’s time, however, Greece was on the rise again, not the least thanks to Nero’s love for everything Greek. Half a century later, the new economic and cultural splendor was consolidated by hellenophile emperors, such as Trajan and Hadrian. This brought some glamor back to Delphi. The sanctuary survived, albeit in a diminished form, until a fire, perhaps intentional, destroyed the temple in the Christian fourth century. Restorations under the short-lived pagan revival of the emperor Julian (360-362 CE) had no long-term effect. In 385 CE, the Christian emperor Theodosius prohibited the practice of divination under penalty of death. At the time, Delphi had already ceased to give oracles.

Clarus and Didyma

During the Imperial epoch, two other oracular shrines of Apollo eclipsed Delphi’s fame by far. Both were situated in Western Asia Minor, in the old colonial region that the Greeks knew as Ionia and that the Romans had organized as the province of Asia; it contained several impressive and old cities, from Smyrna and Ephesus in the north to Miletus in the south. One was the shrine in Clarus outside of the city of Colophon not far from Smyrna, the other the sanctuary of Didyma in the territory of Miletus. Both sanctuaries date back well into the Archaic Age; at that time, however, Didyma was much more important and visible than the rather small shrine at Clarus.

Clarus is mentioned already in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. Its oracle, although not far from Lydia, did not attract the attention of Croesus, unlike the oracle of Didyma; it must have been too small, as was another oracular shrine of Apollo, at Gryneum, not much further north. The Clarian sanctuary lies in a small valley between Colophon and its harbour city Notium, and was surrounded by a sacred grove, as were the shrines of Didyma and Gryneum and many other temples of Apollo and his son Asclepius. The excavated temple remains belong to early Hellenistic times. But its greatest fame came later, when it had grown into an important international sanctuary, thanks to the sponsorship of Roman generals and emperors. Recent excavations have brought to light the main altar of the temple with provisions for the sacrifice of a hecatomb, one hundred cows or bulls: a lavish offering to the helpful god. During the second and third centuries CE Clarian Apollo was consulted by embassies from small and large cities in Western, Central and Southern Anatolia and as far north as the Hellespont, and he was so famous as to appear in some magical texts in far-off Egypt. The fame of Clarus survived into Christian times, despite the end of the cult imposed by the new religion: in some of its oracles, Christian writers argued, Apollo had spoken out in favor of monotheism. When asked “What is God?,” he had answered in a long hexametrical text which begins thus: “Born from itself, teacherless, motherless, unshakable, not giving in to one name, but having many, living in fire: this is god, and we, his messengers (ángeloi) are a tiny bit of God.” The text impressed a Christian thinker enough to cite it, centuries later, in a Christian collection of pagan arguments for monotheism.

Unlike Clarus, Didyma was consulted by Croesus in the middle of the sixth century BCE. Its history goes back even further than that. Pausanias claimed that the site preceded the settlement of the Ionians, and the myth names it as the place where Zeus had seduced Leto, the mother of Apollo and Artemis. Historical reality is less fantastic. The archaeological record of the sanctuary goes back to the eighth century BCE; the first preserved oracular inscription dates to shortly before 600 BCE. At that time, the sanctuary stood alone in its sacred grove, about ten miles south of Miletus to which it belonged politically. Milesians could reach it by sea: the sanctuary had its own small harbor. If they preferred, they could walk: a long and splendid sacred road connected the city with its outlying sanctuary; processions regularly used it. The last part of this road, before it entered the sanctuary, was built as an alley of magnificent statuary, after the example of monumental entrances into Egyptian temples; Milesian merchants had been doing business in Egypt and must have been deeply impressed by its splendor. Today, most of the statues are in the British Museum: an impressive monumental lion, statues of local dignitaries, princes, and aristocrats, but especially oracular priests, solemnly sitting on their thrones. The priests must have belonged to the clan of the Branchidae whose members were running the sanctuary in the Archaic Age: the major priest, the ![]() or prophet, had to come from this family. Their mythical ancestor Branchus was Apollo’s boy lover and, as in other cases, the god rewarded the boy with the gift of prophecy (Conon, FGrHist 26.33).

or prophet, had to come from this family. Their mythical ancestor Branchus was Apollo’s boy lover and, as in other cases, the god rewarded the boy with the gift of prophecy (Conon, FGrHist 26.33).

After Croesus’ misguided decision to attack the Persian king, bringing about his own downfall, the Persians conquered and ruled Asia Minor. We lack information about the fate of Clarus; again, as when Croesus disregarded it, it must have not been significant enough to attract attention. The noble Branchidae however, we are told, surrendered eagerly and handed over their treasure to the Persians. This did not prevent the destruction of their sanctuary, together with the city of Miletus, as a brutal reaction to the revolt of Ionia against the Persians in 494 BCE. When the Greeks liberated Ionia after the battle of Salamis in 479, the Branchidae went into exile to Persia, together with their treasures and the cult statue. Xerxes gave them a city; a century and a half later, Alexander destroyed it, and his successor Seleucus brought the statue back to Didyma. During most of this time, the sanctuary must have stayed silent, although annual processions from Miletus to Didyma resumed immediately after the liberation from the Persians. The oracle itself sprang back into life for Alexander, proclaimed his divine descendance, and foretold his victory over the Persians. Seleucus in turn not only returned the cult image, he also initiated the rebuilding of the temple on a much grander scale: this is the temple whose imposing ruins still stand today. The sanctuary rapidly grew rich and survived the vicissitudes of late Hellenistic history surprisingly well, pirate raids included. But its most prosperous phase came, as with Clarus, under the philhellenic emperors of the second century CE. The emperor Trajan not only paid for the reconstruction of the sacred way from Miletus to Didyma, he even accepted the office of honorary prophet, as did his successor Hadrian and, much later, the emperor Julian whom the Christians called “the Apostate.” Together with the entire Mediterranean world, the sanctuary suffered from the economic and military crisis in the third century, and even more from the hostility of the Christians. A Christian author gleefully preserves the oracle with which Apollo answered the emperor Diocletian when he consulted the god about how to treat the Christians: Apollo was plainly hostile to Christianity (Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum 11). The end, however, was inevitable, and the edict of Theodosius that outlawed divination sealed the fate of this sanctuary as well. To mark the Christian victory, the innermost sanctum of the temple, the very place where the prophetess had sat and relayed the god’s messages, was converted into a church.

METHODS OF DIVINATION

There were many methods of divination, in ancient Greece as elsewhere; this is not the place to list them all. One method, however, seemed to be the most widespread, and the most noble in the eyes of the Greeks: ecstatic divination, or, as Socrates calls it, madness (manía). “The best things,” Plato has him say,

arrive with us through madness when the gods give it as their gift. The prophetess in Delphi and the priestesses in Dodona have worked many gods for the Greeks, both for private men and for states, when they were in a state of madness, while they did little or nothing when they were in a sober mind. And if I would also talk about the Sibyl and all the others, I would unduely draw out my discourse.

(Plato, Phaedrus 244 ab)

And in order to underline his point, he resorts to etymology: does not the Greek term for the science of divination, téchn![]()

![]() derive from the term for science of madness, téchn

derive from the term for science of madness, téchn![]()

![]() This etymology is whimsical and playful, but it makes its point: “mad” divination is the main Greek way to gain access to divine foreknowledge. The Delphian Pythia, the prophet in Clarus, the prophetess (and, perhaps, before the interruption worked by the Persians, the male prophet) in Didyma as well as the Sibyl or Cassandra uttered their prophecies in an abnormal state of mind, beyond sober rationality. They were, to the Greeks, éntheoi, “having a god inside,” or kátochoi, “held down,” being controlled by a superhuman agent.

This etymology is whimsical and playful, but it makes its point: “mad” divination is the main Greek way to gain access to divine foreknowledge. The Delphian Pythia, the prophet in Clarus, the prophetess (and, perhaps, before the interruption worked by the Persians, the male prophet) in Didyma as well as the Sibyl or Cassandra uttered their prophecies in an abnormal state of mind, beyond sober rationality. They were, to the Greeks, éntheoi, “having a god inside,” or kátochoi, “held down,” being controlled by a superhuman agent.

It is not easy to translate what this meant to the Greeks into our own cultural perceptions. Historians of religion usually called all this possession, even spirit-possession, and psychologists made a case that the ability to enter such a state may be common to all humans. Even if this is true, it has also become clear that every culture has its own set of phenomena that manifest themselves in such an altered state of consciousness, and its own way of thinking about them. Modern anthropologists and historians of religion prefer the term (spirit-) possession to any other, thus following the lead given by the Greek term kátochos; the term, however, seems to have a somewhat negative Christian bias. The Gospels as well as many saints’ Lives tell stories about demons possessing a human being and driving it into all sorts of antics. The saint or Christ himself has to restore serene normalcy by driving out the demon: autonomy of the mind seemed preferable to superhuman control of it. But there is also, at least in early Christianity, a positive view of such experiences, presumably carried over from the Jewish prophets. Paul is aware that God, or rather his Spirit, can grant “the gift of prophecy” or “the gift of tongues of various kinds” (1 Corinthians 12:7-10), and he is not averse to this, since it may show “that truely God is in you” (1 Corinthians 14:25). After all, he had such an experience himself when he “was caught up into paradise and heard words so secret that human lips may not repeat them” (2 Corinthians 12:4). However, once Christianity developed a strong hierarchy with the aim of controling religious teaching and spiritual life, Church authorities realised that it was easier to control minds that were not able and even proud to receive their own divine revelation. Thus, already in the third century CE the Montanist Christians, a group that practiced individual prophecy, were outlawed as heretics.

Paul’s description of the church of Corinth makes another point. The altered state of consciousness of his congregation could take many forms, among them prophecy and glossolalia (speaking in tongues), but also healing, miracle-working, or interpreting the words of those who were speaking in tongues. Modern assessments of these types of ritual behavior - as frenzy, ecstasy, chaos, or loss of control - are unable to do justice to such a variety of forms. In order to keep away from such notions, I prefer to use the term “inspired divination,” in the case of Paul or the Montanists as well as for Apollo’s prophets and prophetesses.

THE PROPHETS OF APOLLO

The Pythia

The medium in Delphi was usually called the Pythia, reflecting simply that she was a part of the religious establishment at Pytho, Delphi’s other name. When the Pythia becomes visible through our texts, she is a mature woman: in the opening scene of Aeschylus’ tragedy The Eumenides, she describes herself as old (v. 36), and vase paintings of this scene show her with white hair. A much later account explains her age as the result of a reform: originally, the Pythia could be a young woman and a virgin, but when a Thessalian raped a young and very attractive Pythia, the Delphians decided that, in order to avoid further incidents of this sort, no Pythia should begin her office before the age of fifty. But even being an old woman she should wear a maiden’s dress in memory of the former state of affairs (Diodorus of Sicily, 16.26). The dress was more than just a symbol: during her time in office, the Pythia was always supposed to live chastely; but since she was not elected before a mature age, she could not be expected to have lived a celibate life during the many preceding years. And virginity was never a condition for election: in some inscriptions, proud Delphians claimed the Pythia as their grandmother. However, a virginal life was expected from her colleague, the prophetess in Didyma; here, nothing is said about an age limit, and it seems reasonable to assume that the Didymean prophetess was elected as a young girl into a life of permanent celibacy.

Behind all this is a specific view of inspiration and sexuality. Christian authors could be quite crude about it, for obvious reasons: Apolline inspiration competed with their own inspired religion, and they did not like it.

They say that this woman, the Pythia, sits on the tripod of Apollon and spreads her legs; a nefarious vapor enters her body through her genitals and fills the woman with madness (mania ): she loosens her hair, falls into a frenzy, has foam around her mouth and utters words in a state of madness.

(John Chrysostom, Homily in 1 Corinthian 29, 260 BC [after 350 CE])

This is a polemical parody of a divinatory session in Delphi which did not just influence all later Christian authors; modern accounts of the frenzied Pythia leave out the sex but keep the foam. But as with every successful parody, there is a factual basis to it, although heavily distorted. Apollo, as we saw already with Branchus, distributed prophetic gifts as rewards for sexual gratification. Furthermore, in some descriptions of possession, there was a sexual undertone: it was unmistakable when Virgil described the possession of the Cumaean Sibyl by Apollo (Aeneid 6.77-80), and Herodotus told how the ecstatic priestess of Apollo in the Lycian city of Patara slept with the god in the sanctuary (1.157). Similar ideas are found in other cultures as well. This explains why the Pythia, Apollo’s prophetess, had to be a virgin, no human’s lover: the god is a jealous lover, as many of his myths make clear, and he would not bestow the gift of prophecy upon someone else’s beloved. If this condition was impossible to meet, as with many Pythias, it could at least be created by ritual: there is no need to think that a Pythia was always a young girl.

We do not know how a Pythia was selected. Presumably, she had to show a disposition for mediumship, but no sources tell us whether or how this was tested. In Imperial times, some Pythias came from leading families in Delphi, just as the Didymaean prophetesses of that period came from the leading local families of Miletus: a disposition for mediumship might be hereditary and bring prestige. On the other hand, Plutarch the Delphian priest is aware that the woman who was serving as Pythia in his time “grew up in the house of poor farmers and brought no poetical skill or any other faculty and experience with her: … inexperienced, uninformed in almost everything and a virgin in her soul, she is together with her god” (On the Oracles of the Pythia 22. 405 CD). And as with every other Pythia, she was prevented from gaining more experience during her entire period of office. She lived in her own house, somewhere inside the sanctuary, and was carefully isolated from contact with any foreigner. This may have been intended to keep her from being unduely influenced by any client’s interests.

Most of the time, a Pythia’s life must have been fairly monotonous, if not outright boring. Originally, our sources assert, the god only spoke once a year, on his birthday - the seventh day of the spring month Bysios. Later he deigned to answer once every month, or more frequently when special guests came. But even then, the Pythia might in the end remain silent. Whoever sought the god’s advice first had to pay a fee and then had to offer a sacrifice, usually a goat - had not Apollo promised abundant sacrificial meat to the shocked Cretans whom he had abducted as his first priests? His imposing marble altar, a gift from the island state of Chios, is still visible next to the temple doors. Before being killed, the sacrificial animal was drenched in water: if it did not very vigorously and audibly shake the water off, the god was not ready for consultation. This developed from regular Greek sacrificial practice; there, the animal was sprinkled with water to make it nod its head as if consenting to the sacrifice. The Delphic practice exaggerated the traditional rite: there was more at stake than the simple consent of the victim, the god must also be willing to communicate intimately with the Pythia. We know of one case when the priests forced the Pythia to prophesy despite the goat’s bad omen: she lost her mind and died a few days later. However, if the sacrificial animal signaled the god’s agreement, the Pythia entered the most holy room (ádyton), took her place on the tripod, Apollo’s sacred symbol, and waited for the answer from the god. To prepare herself, she bathed with water from one of the sacred springs, Castalia, and fumigated flour on a small altar in the sanctuary. The adyton was in the innermost part of the temple, though all archaeological traces have been destroyed by the construction of a church. Archaeologists have discerned the traces of a barrier (or a thin wall) that separated the first third of the temple’s interior from this innermost part. While some personnel - a priest, a prophet (if he is not the same as the priest), the “Sacred Men” - accompanied the Pythia into the adyton, the client waited in this ante-room from which he could at least hear, if not see the Pythia.

The details of how the Pythia communicated with her god are still highly debated. A French scholar remarked pertinently: “The last Pythia took this knowledge with her into her grave.” Two issues are crucial: did she prophesy in ecstatic frenzy (as John Chrysostom graphically depicted), and was she possessed by the god? Opinions have diverged widely over time. Ancient accounts are few and contradictory, and the crucial area of the temple is lost beyond restoration. Lack of evidence has never prevented scholars from attempting answers, however. For a long time, it seemed accepted knowledge that the Pythia prophesied in an incoherent ecstasy, caused by gaseous emanations arising from the soil; the priests then turned her babblings into proper hexameters, and inserted their own political reading. More recently, scholars have objected to the crude materialism and simplistic Machiavellianism of this picture. Although some ancient sources mention specialists who were versifying the Pythia’s utterances should they be in prose, this does not mean that the Pythia talked gibberish, or that the priests needed such an instrument of political manipulation. Thus, scholars preferred to understand her as a spirit medium comparable to modern examples such as the famous Madame Blavatsky, with the god entering into her and using her vocal organs as if they were his own. Others again, still thinking of ecstatic frenzy, followed a lead in a Byzantine author that she was chewing laurel; well before drug-induced trance became fashionable after 1968, these scholars assumed that the leaves contained a hallucinogenic substance which brought about her ecstasy. Other late sources tell that she was drinking water from a sacred spring that flowed in the adyton; this was recently combined with reports of possible hallucinogenic vapors into the hypothesis that this water contained traces of a psychotropic substance.

Over time, most of these ideas have been disproved. Chemical analysis showed that laurel does not contain any hallucinogenic substance, and archaeologists who valiantly tried to chew it ended up with nothing more spectacular than green teeth. Archaeological excavations showed no trace whatsoever of a spring in the adyton; a small spring, the Cassotis, was flowing at some distance uphill from the temple, but its water never entered it. More fundamentally, it has been shown that the Pythia did not speak in frenzied ecstasy, with loosened hair and foam around her mouth, or in tongues as Paul’s Corinthians. Ancient accounts about the actual session insist on the serenity and clear language of the Pythia, and vase-paintings always show a composed female prophetess sitting on the tripod, be it the Pythia or her mythical predecessor, the goddess Themis; vase painters were able to depict ecstasy, as the many menads on Greek vases show. Only one pagan text talks about her frenzy, but this was the result of her being forced to enter the adyton against her own and the god’s will; this was the incident that killed her. Plutarch contradicts the idea that the god spoke through her vocal organs; he insists that one heard only the Pythia’s voice: “Neither the sound nor the inflection nor the vocabulary nor the metrics are the god’s, but the woman’s; he grants only the inspiration and kindles a light in her soul towards the future; such is her enthousiasmós” (On the Oracles of the Pythia 7.397 CD). And his contemporary Dio Chrysostom, a famous orator from Prusa in Western Anatolia, pointed out that Apollo would speak “neither Dorian nor Attic” nor any other human language, but that it was the medium’s language one was hearing: the Pythia basically was a translator of Apollo’s thoughts, and if already translations from one human language into another are always defective, even more so the translation from god to human: “That is why oracles are often unclear and deceive humans” (Oration 10.23). Thus, far from being frenzied and talking in tongues, the Pythia as a translator is as much traduttore as traditore, in the famous Italian saying.

All this does not mean that the Pythia, when prophesying, was in an ordinary state of mind: she could quietly and lucidly answer the questions of her clients, and nevertheless be in that altered state of consciousness that her own culture associated with being inspired. After all, everybody agreed that she prophesied in a state of mania, madness, and that she was kátochos, controlled by Apollo. In the Eumenides, Aeschylus has her talk on her own function: “I tell the future wherever the god leads me” (Eumenides 33). He is in control, not she: “The god makes use of the Pythia in order to be heard by us” (Plutarch, On the Oracles of the Pythia 21.404 D).

Control, however, is ambivalent. It can come from outside, as with a puppet on a string, or from within, with the god slipping into a human body. Both views are found in antiquity. “It is utterly simplistic and childish,” says one of the interlocutors in Plutarch’s On the Obsolescence of Oracles, “to believe that the god himself would slip into the body of the prophetess (as in the case of the bellytalkers who … are now called Pythones) and that he would speak using their mouths and vocal chords as his instruments” (9. 414 DE). This protest has a theological basis. The divine world is essentially different from the human - how could a god slip into a human body? But the vehemence of the criticism shows that the very idea existed, and that Apollo could be understood as a body-snatcher, in Delphi and elsewhere. Why else would the bellytalkers (Greek engastrímythoi, “having words in their bellies”) be called Pythones, with a word that is again connected with Delphi’s other name, Pytho? But Plutarch’s friend, as other ancient observers, opted for the other solution: the god controlled the Pythia from outside.

Despite the many voices that insist on the Pythia’s serenity, the view that Delphic prophecy implied some sort of violent trance is not entirely unheard of in antiquity. It existed in the Christian parody; and the parody was based on pre-Christian stories. There are two competing myths about the origin of the Delphic oracle. One is the story told in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, where the god himself founded his oracle after having killed a dragon, and where he called the place Pytho, “Stinkton,” after the stench of the dragon’s rotting body. The other is the account of how Delphi’s divinatory properties were discovered; here, these properties pre-exist the foundation of Apollo’s sanctuary. The story is attested long after the Hymn: it is repeated in several sources with only minor variations, from Diodorus of Sicily in the first century BCE onwards; parts of it are alluded to as early as Aeschylus’ Eumenides. In this story, a herd of goats was instrumental in discovering the source of the oracle. In very early times, these goats were grazing around a chasm in the ground which channelled subterranean gas to the surface. This was the spot where the adyton of the sactuary would be located. Goats that happened to breathe the gas pranced about strangely and made unusual sounds, a sort of goatish glossolalia. When this happened repeatedly, one curious goatherd inspected the spot, inhaled a whiff of the gas himself, and promptly began the same sort of outlandish behavior. The travel writer Pausanias even credits him with fully formed Apolline oracles. Whatever it was, news of the occurrence attracted a crowd who, in turn, shared the same ecstatic experience. The early Delphians founded an oracular shrine on the spot and dedicated it to Gaia, the goddess of what there is in the earth. Later, the oracle was taken over by Themis, goddess of divine justice, and finally by Apollo, its present-day owner. The story explains the role of the goat as the main sacrificial animal. Goats were as susceptible as humans to the phenomenon, and thus came to play a major role in the oracular ritual. It also defines the state of consciousness in which humans gave oracles as ecstatic (enthousiasmós, in Plutarch’s words); it attributes this to the force of a subterranean gas that was fed into the adyton; and it sketches a divine history of the oracle: from an oracle of Gaia, it developed into an oracle of Apollo.

Thus, there is a double tension already inherent in the ancient accounts of Delphi and its prophecies. First, as to the Pythia being controlled by the god: Some understood this as the result of possession, with the god entering the Pythia’s body, others contradicted this view on theological grounds. Secondly, as to this control expressing itself as an altered state of the Pythia’s consciousness. In the foundation myth, this took the form of ecstatic behavior and even some sort of glossolalia, whereas in the reality of the oracle’s daily practice, the Pythia spoke in her own voice, either in hexameters or in a prose that experts then versified. This double tension has to be explained. For practical reasons, any divinatory system tries to keep the line of communication between the divine source of information and the human client as short as possible. The shortest distance possible would be the immediate revelation of a god to a human, but this happens very rarely in any religion. Given the essential gap between god and human, some distance is unavoidable, and in the cultic reality of Delphic divination, it is the Pythia - a human being who has a special relationship with the god - who bridges the divide. The myths, however, extrapolate from this to indicate a much larger distance between humans and gods. Possession by a god means the loss of a vital and central part of one’s humanity - loss of control, memory, and identity. Both views, the mythic and the cultic, are necessary for the function of the oracle where two such incompatible worlds, god and humans, come together, and they supplement each other. Modern scholars created a monolithic theory out of what in reality had only been complementary views.

This leaves us with the mysterious gas, the source of inspiration and ecstatic behavior both in the foundation stories and Christian polemics. Its existence and role had been challenged already by Plutarch; the Church Fathers took it as a given, since such a materialistic view helped them to unmask the oracle as substance abuse. In the first century BCE, the geographer Strabo described the adyton as

a cave, very deep but not very wide at the top, out of which an inspirational gas (pneuma enthousiastikón ) was rising and over which a high tripod was set; the Pythia ascended it, received the gas, and prophesied in prose and in metre.

(9.3.5)

Other sources concur and make the gas a standard feature, and one might even be tempted to derive the name Pytho with its easy etymology (“Stinkton”) from a very specific and not very agreeable smell in the region. The French excavations of the temple that started in the late nineteenth century found only solid rock, with no visible chasm or cave out of which a gas could rise. This seemed to be the end of the story: archaeology, once again, had exploded the ancient myths.

The reality, however, seems to be more complex. Among Apollo’s oracles, Delphi is the only site where we hear of a gas as the source of the medium’s ecstasy. Under another oracular temple of Apollo, in Hierapolis in Phrygia, a late philosopher claimed to have found a cave in which toxic gases collected; excavations have confirmed it. But no ancient source connects this with ecstatic prophecy; inscriptions attest only to a lot oracle in this sanctuary. Moreover, no one ever came up with a convincing explanation as to why so many ancient sources mention vapors rising from a chasm in the adyton to induce the Pythia’s trance: why not assume that they, after all, knew more than we do? And it seems that antiquity may have been finally vindicated. A few years ago, the Greek government ordered a geological survey of the wider region of Delphi, for reasons that had nothing to do with archaeology: the government needed a site for an underground waste deposit that would be safe from earthquakes. The geologists found two fault lines that cut through the mountains behind Delphi; they cross each other exactly under the adyton of the sanctuary. The original French excavation reports in their turn had mentioned tiny fissures in the rock, but they were dismissed as insignificant: conditioned by the ancient sources, the archaeologists were looking for the chasm or cave mentioned in the texts, not for minuscule cracks, although even those could have released subterranean gas. More interestingly still, the faults lead down to geological layers that carry petroleum and from which gas might emanate. Chemists surmise that these fumes might be related to the kind of gas used as an anaesthetic in nineteenth-century dentistry. Rising through the fissures, it would have appeared above ground; the smell may have led to the installation of the oracle. And if it collected in the closed space of the adyton, its presence would have been even more strongly felt.

But there are still problems with such an explanation. Already Plutarch had insisted that only the Pythia was affected by trance, never her attendants in the adyton or any other person in the temple. Yet would not the vapors be dispersed through the entire interior of the temple (On the Obsolescence of Oracles 46)? Plutarch used this observation as an argument against any presence of vapors; the Platonist could not agree with a material explanation. But it might simply show that, whatever substance it was, it was not strong enough to induce trance; it simply smelled. And there is no urgent need to explain the trance in purely material terms. Trance, like any altered state of mind, can be induced by mental processes alone; it is a conditioned reflex, set off by any sensory trigger to which a susceptible person has been conditioned. In the case of Delphi, the Pythia had been well prepared for her encounter with the god through a series or ritual acts, from a preliminary bath to sitting on the tripod; the smell of the gas might function as the final trigger. In our present state of knowledge, this is not much more than a hypothesis that may explain some of the idiosyncrasies of the Delphic oracle. Future archaeological research is needed in the adyton to verify the presence of fissures and, if possible, to trace the source of the gas, if there was gas.

Clarus and Didyma

There are those who give oracles having drunk water, such as the priest of Clarian Apollo in Colophon; others are sitting over openings in the ground, such as the women who give oracles in Delphi; others again are breathing inspiration from water, such as the prophetesses in Didyma.

With these words, the Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry (243-ca. 305 CE) characterized the inspirational methods in the three major oracle shrines of Apollo (Iamblichus, On the Mysteries of Egypt 3.11, p.123.14). Like Plato, he emphasized divine inspiration as a divinatory method, whatever the exact method of achieving it: the Neoplatonists were convinced that ecstasy was the only route to knowledge of the supreme god.

Clarus

Clarus and Didyma have the use of water in common. Both sanctuaries are built around a sacred spring; both are well excavated: this supplements the meager literary record. In the Clarian sanctuary, the spring flowed in an underground chamber, at the very end of a somewhat labyrinthine subterranean floor under the temple; this spring chamber was directly under the image in the temple cella (figure 5). From its front hall (pronaos), two symmetrical flights of stairs led into a narrow hallway that opened into a large chamber with benches on two sides. From here a passage led into the small spring chamber. When asked to prophesy, the priest descended into this chamber, drank from the spring, entered into inspired contact with his god and answered in verses; like the Pythia, he was “a man without great knowledge of letters and poetry.” According to the historian Tacitus, who gives us this description (Annals 2.54), he did not even know the question: “It was enough to hear the number and the names of the visitors.” It was the visit of the prince Germanicus in 18 CE which prompted Tacitus to this description; “we are told,” Tacitus concluded his account, “that he predicted an early death to Germanicus,

Figure 5 Sanctuary of Apollo in Clarus, late fourth century BCE. View of the underground chamber from the west. Copyright Vanni/Art Resource, NY.

although in an ambiguous way, as oracles are wont to do.” This description, the only substantial one we have of a visit to Clarus, is vivid and detailed; perhaps Tacitus was drawing on the memoirs of Germanicus’ wife Agrippina who traveled with her husband.

Germanicus, the descendant of Augustus, and a visitor of distinction, could presumably descend into the underground chamber; but he had to wait on the benches in the larger room. From here, he would have heard the murmur of the spring and the verses spoken by the inspired priest. Not everybody, however, was allowed to come so close: in order to “go down” (embateuein), one had to undergo an initiation, a presumably costly privilege offered only to the select few. Throughout Greece, initiations were a ritual means of entering into close and often personal contact with a divinity. At the same time, the ritual imposed utter secrecy on the experience of such an encounter: this must have been true for Clarus as well. Ordinary clients waited upstairs, in the pronaos of the temple, for an attendant priest to bring them the oracle’s answer, written down and sealed.

At least when a city sent an ambassador to Clarus, as cities did with all oracles (nor had Croesus traveled to the shrine, but he sent an emissary), he was not supposed to learn the god’s answer before his return. Once he was back in his city, he would report to the assembly; only then, he would break the seal and read the text. His voice served as a substitute for the god’s, as it does in this oracle for the city of Pergamum:

To you, descendants of Telephos - you are living in your lands, more honored by king Zeus than most others, and the children of thundering Zeus, his gray-eyed daughter Athena who withstands all wars, Dionysus who makes forget pain and makes grow life, Asclepius the healer of evil disease; among you, the Kabiroi, sons of Ouranos, were the first to see new-born Zeus, when he left his mother’s womb on your acropolis - to you, I will tell with unlying voice a medicine in order to escape a terrible plague….

(Merkelbach and Stauber, Epigraphica Anatolica 27, 1996, 6 no. 2.1-11)

The text is too long to be cited in full, but its style is clear: it is a complex poetical composition in which the god addresses the city directly. He evokes its mythic history and its major myths and cults: the city as the birthplace of Zeus, founded by Zeus’ son Telephus, and protected by Zeus and Athena, whose sanctuaries were on the acropolis, and by Asclepius, whose healing sanctuary at this period, the mid-second century CE, was one of the major sanctuaries of the region. The god, it seems, was well adapted to an age that had a mania for mythic history, and preferred a poetic style that privileged almost baroque complexity over unadorned simplicity.

Didyma

Whereas the priest in Clarus drank the water from the spring in the sanctuary, the prophetess at Didyma had a less direct contact with the sacred water. After Seleucus had brought back Apollo’s statue from Persia, the Milesians replaced the earlier temple with an unusual and monumental building that centered on a sacred spring. From the outside, the building looked like an ordinary temple, albeit a very large and roofless one. A flight of steps led to the impressive pronaos with two rows of giant columns in front of the main entrance. This monumental entrance did not lead into a cella, as in any other temple: its double doors opened over a threshold that was almost as high as a man. No human could step over it; it led into another realm. On the other side of the threshold, a flight of stairs descended into the main space, a monumental roofless enclosure that took the place of the usual cella. Its high walls surrounded a large open area containing a small temple that sheltered the sacred spring. At the beginning of a prophetic session, the prophetess either dipped her foot into the spring water or wetted the hem of her sacred dress with it: this was enough to send her into a trance. Like the Pythia, she uttered her oracle while sitting on a special seat; our only source calls it “axle” (axôn), whatever that means (Iamblichus, On the Mysteries of Egypt 3.11, p.127.6). She had prepared herself for this task by bathing and fasting, methods commonly used to purify oneself for an encounter with a god. Visitors to the oracle, one imagines, were waiting in the vast pronaos: after a preliminary sacrifice to Apollo, they had already handed over their request to a temple attendant. Then, once the prophetess had uttered her oracle, a priest walked up to the door and repeated the text to its addressee, or perhaps handed it down in written form. We know some of these oracles from inscriptions that were dedicated in Miletus, or in the sanctuary at Didyma itself. Other oracles are transmitted in literary sources, not least the Neoplatonist and Christian authors who were interested in the theology contained in Apollo’s answers. Didymaean oracles of the second century CE are couched in verses just as grandiose as those from Clarus: Apollo had adapted to the style of the epoch in Didyma just as he had in Clarus.

We have no information from either place about the characteristics of the sacred water that inspired the prophets. Was it ordinary spring water, or did it contain a hallucinogenic substance such as some scholars have suspected in Delphi? Iamblichus rejects the claim that “a divine spirit (pneûma) passed through the water” of Clarus, whatever that meant (On the Mysteries of Egypt 3.11, p. 124.17). The learned Pliny insisted that the Clarian water, while it inspired the priest, also shortened his life, but he did not explain why this was so (Natural History 2.232). One could suspect that the water was enriched with minerals: the wider region is rich in mineral sources - the hot springs of modern Pamukkale are not that far away, and closer still are other hot springs, the bath of Agamemnon where the king of Mycenae was cured of an ailment during the Trojan War; it still functions as a spa that cures rheumatism. However, the water that nowadays fills the Clarian temple basement is ordinary groundwater that is seeping in from the local river. The Didymaean source provided the locals with water in times of crisis, and none of them began to prophesy. And no mineral water has ever been known that would induce ecstasy: again, we are probably dealing with a conditioned reflex of the medium who was carefully prepared for the task.

Other Apolline oracles are also said to have made use of water or, in one case, of the blood of a sacrificial victim; animal blood is even less likely to contain hallucinogens than is mineral water. More importantly, the use of liquids as a trigger for inspirational divination is wide-spread in Apolline divination; Delphi with its chasm and its vapor is the one exception. But Delphi had sacred springs too. There was the small spring a few yards above the temple, the Cassotian Spring or Cassotis, and the large and famous source outside the sanctuary, the Castalian Spring or Castalia; the Castalia provided the water for the Pythia’s preliminary bath. It is at least conceivable that in late antiquity, when Delphi paled before the fame of Clarus and Didyma, their rite, drinking sacred water, was introduced in Delphi as well. There are two authors from the second century CE, the satirist Lucian and the travel writer Pausanias, who affirm that the Pythia drank water from a sacred spring. Lucian combines water drinking with chewing laurel, and Pausanias claims that the Cassotis went underground and surfaced again in the adyton. This, however, is not accurate, for as we saw earlier, the latter is disproved by the excavations and and the former by experiment. And there is no earlier evidence for Delphic water-drinking: either Delphi adopted the practice of the more successful shrines, or the information we have is simply wrong.

OTHER PROPHETS: CASSANDRA, HELENUS, THE SIBYL

Apollo’s role as patron of divination did not manifest itself only in specific oracular shrines. At least in mythology, many seers also were closely connected with him.

Cassandra

Mythical Troy had two seers, both children of king Priam: the twins Helenus and Cassandra. When their parents visited the shrine of Apollo Thymbraeus not far from Troy, they left the twins behind in the sanctuary. Coming back next morning, they found them asleep, and two snakes were licking their ears and eyes: this is why Helenus could hear the voice of the gods, as the Iliad has it (7.53), and why Cassandra had prophetic visions. But unlike Helenus, Cassandra was a highly problematic seer. The most beautiful among Priam’s daughters, not only was she raped by the lesser Ajax in Athena’s sanctuary, she attracted the attention of Apollo himself. The god promised her the gift of prophecy as a reward for her love; but as soon as he had bestowed his skills on her, she refused to surrender, and he took cruel revenge: while he could not remove his gift, he could see to it that nobody would believe her prophecies. Divination can be a problem to the prophet. In his Agamemnon, Aeschylus has Casssandra utter a last ecstatic prophecy in Argus immediately before her death in front of a chorus of Argive citizens. She invokes Apollo who “has ruined me utterly for the second time” (v. 1082), and foretells not only her own murder at the hands of Clytaemnestra, but also that of Agamemnon who had brought her home as part of the booty. The chorus is amazed that she, although now a slave, still prophesies: “The divine remains in the mind, though it be enslaved” (v. 1084). But then they stubbornly refuse to understand her: “Of these prophecies I have no understanding” (v. 1105).

The Sibyl

Another mythical prophetess was the Sibyl, and like Cassandra, her prophecies were ecstatic: “The Sibyl sounds with raving mouth,” according to Heraclitus (late sixth century BCE). She was thought be the daughter of a nymph and a human: the human father made her mortal, the divine mother long-lived (according to some, nine hundred years) and, perhaps, prone to ecstasy; a Greek way of describing that someone was in an altered state of consciousness was to say that he was “seized by a nymph,” nymphóleptos. Over the centuries, several places in the ancient world claimed to have been the home of the Sibyl, from Babylon to Praeneste in Italy. Ancient scholars solved this problem by assuming a plurality of Sibyls: this is why, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo could combine Biblical prophets with Sibyls as the representatives of pagan and Biblical prophecy. Many Sibyls were thought of as priestesses of Apollo - such is the case with the Sybil of Erythrae in Ionia, the Sibyl of Troy who was a priestess of Apollo Smintheus, or the most famous one, the Sibyl of Cumae in Italy. When, in Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas visits her, he finds her in the vicinity of the temple of Apollo that was on the town’s acropolis (Aeneid 6.9-10). Another Sibyl was connected with the sanctuary of Delphi. Not far from Apollo’s temple, visitors were and are still shown a rock on whose top “the first Sibyl sat after her arrival from Helicon, where she had been reared by the Muses” (Plutarch, On the Oracles of the Pythia 9): like the Muses (and like the Pythia), the Sibyl spoke in hexameters. And like the Pythia and Cassandra, the Sibyl was a virgin, for the very same reason: it was Apollo who claimed exclusive control over her sexuality.

But unlike the Pythia whose oracles were spoken and reflected the knowledge of Apollo himself, the Sibyl prophesied alone. Unlike the Pythia, she could no longer be consulted in person: she was dead in historical times, despite her life-span of nine hundred years; instead, her oracles were collected in books. Rome was said to possess three of these. According to legend, an old woman - the Sibyl of Cumae, as it turned out - visited the Roman king Tarquinius Priscus and offered him nine books; they contained, as she claimed, the fates of Rome. Tarquinius refused to buy them; the Sibyl burned three of them and insisted on the same sum of money. The king refused once more, and the Sibyl burned the next three while still demanding the same price. Finally, perplexed and angered, the king gave in and bought the three remaining books. These offered guidance to the Roman senate in times of crisis: at such moments, the senate would order one of its standing committees, the “Committe on the Performance of Rituals” (de sacris faciundis), to consult the books and relate the oracle to the senate. The books were kept on the Capitol in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the main god of the Roman state. When in 83 BCE the temple burned down, the books were destroyed with it. The senate set up a committee that was to collect samples of Sibylline oracles from all over the Mediterranean world and to find out which of the rival Sibyls was the “real” one. When the committee selected the verses of the Sibyl from Erythrae, the senate sent its members to the small Ionian city to buy all the available verses and to organize them into a new set of Sibylline books. Later, the emperor Augustus had the books transferred to his new temple of Apollo on the Palatine. It proved to be a wise decision, since the Capitoline temple burned down again during the civil war of 69 CE. Apollo proved a better guardian of the Sibyl’s verses than Jupiter had been, and only the Christianization of Rome ended the consultation of these books.

At that time, the Sibyl herself had been adopted by the Christians. Since she was speaking in her own name and not in Apollo’s, any god could inspire her. In the struggle of Judaism against hellenization, the Sibyl turned into a prophetess inspired by the One God, who had already inspired his own prophets in their fight against over-powerful Jewish kings. After the rise of Christianity, the Sibyl again switched sides: her oracles began to “predict” the arrival of Christ, his miracles, and his Passion. The Emperor Constantine, impressed with these prophecies, issued “from the temple of foolish superstition” (Oration to the Saints 18-21); his contemporary, the Christian writer Lactantius, collected the parallels between the sayings of the Biblical prophets and of the Sibyl and showed that these oracles were not fictions, as some pagans asserted, but true prophecies (Divine Institutions 4.15). For this reason, almost the only Sibylline oracles preserved today are a set of eleven books of Jewish and Christian origin.

SUMMARY

Throughout antiquity, Apollo remained the central god of prophecy. His little brother Hermes became the patron of minor divinatory forms, such as lot and dice oracles, and in Dodona and Siwa in Egypt, humans could access Zeus directly to gain information. But it was Apollo’s major shrines - Delphi, Didyma, Clarus - where Apollo informed humans through his inspired priests or priestesses; and there existed smaller sanctuaries that offered similar services. The methods for gaining inspiration - for entering the altered state of mind that opened a window to the god’s mind - varied from oracle to oracle and depended on local conditions. The main principle, however, remained the same: a priest or priestess, selected for the task because of his or her special ability for mediumship, served as the channel of communication between the god and the human inquirer. Mythical figures such as Cassandra, Helenus, or the Sibyl followed the same pattern of inspiration. Oracles from Delphi, Clarus, and Didyma were inscribed on stone and collected in books by pagan and Christian authors, in the latter case to prove Christianity’s claims even through the mouth of a pagan god. In a similar way, Apollo’s inspired prophetess the Sibyl served not only pagans, but Jews and Christians as well, and Sibyls could be paired together with Old Testament prophets to represent the reality and truth of divine inspiration.