Mafia Inc.: The Long, Bloody Reign of Canada's Sicilian Clan - André Cédilot, André Noël (2011)

Chapter 11. PROJECT OMERTÀ

ANOTHER MAN BEING HOUNDED by Canadian tax authorities was Alfonso Caruana, the new head of the Cuntrera-Caruana clan. Try as he might to ignore them, the assessment notices were piling up. In 1986, Revenue Canada had seized $827,624 in his bank accounts as payment for back taxes. After initially contesting the decision, Caruana had given up and flown the coop to Venezuela, hooking up with Nicolò Rizzuto and the Cuntrera brothers.

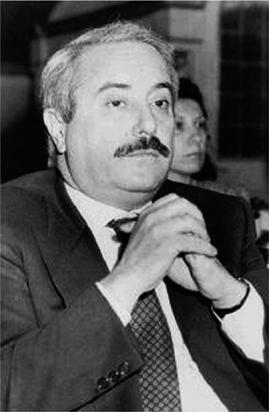

When he returned to Canada in November 1993, the tenacious revenue inspectors were quick to remind him of Benjamin Franklin’s timeless adage about the only certainties in life. The inspectors knew beyond all doubt that Caruana had amassed a colossal fortune in the narcotics trade. The Cuntrera-Caruanas were anathema to Italian judge Giovanni Falcone, who often said of them: “If we wish to destroy the drug trade, we must apprehend them.” Indeed, just three days before his assassination, the anti-Mafia crusader had met with the Venezuelan justice minister to request that the leaders of the clan be extradited to Italy.

René Gagnière, who worked for a special Revenue Canada unit in Montreal, devoted a four-year slice of his career to investigating Alfonso Caruana, which included poring over invaluable data gathered by RCMP Sergeant Mark Bourque. One piece of information in particular caught his attention: in 1981, during a span of just eight months, no less than $21.6 million had transited through one of Caruana’s accounts. The money had been deposited in small bills, withdrawn soon after in the form of bank drafts, then routed to Swiss accounts.

Immediately after Caruana’s return to Canada, Revenue Canada inspectors sent him a new notice of assessment. The amount due was nearly $30 million: $8.6 million in unpaid income taxes, plus accrued interest and various penalties representing a further $21.2 million.

Caruana’s response to the taxman’s request came on March 6, 1995: he filed for bankruptcy, declaring assets of $250. At the time, the self-described pauper was living at his sister-in-law’s house on Grosvenor Avenue, in Westmount, Montreal’s richest neighbourhood. He soon quietly moved with his wife to an elegant home in Woodbridge, just north of Toronto.

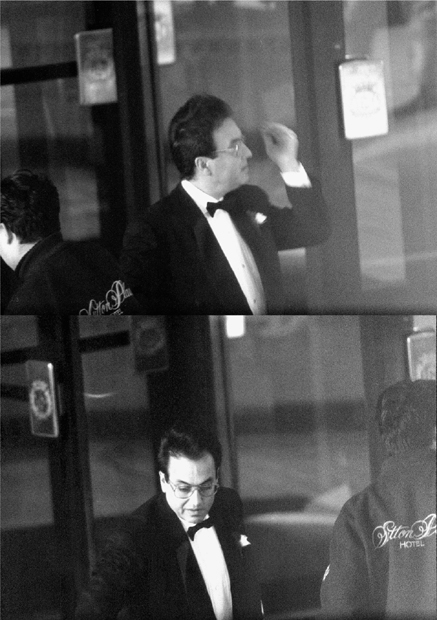

On April 29, as he entered the upscale Sutton Place Hotel on Bay Street in Toronto’s downtown core, an unsuspecting Caruana was caught on videotape by Detective-Constable Bill Sciammarella and his unit based in the town of Newmarket, also north of the city. Using a camera hidden behind a window in a government building across the street, the police were conducting a favoured and almost always productive brand of surveillance: they were filming a Mafia wedding.

Among the tuxedoed guests, police recognized Vito Rizzuto and several of his henchmen: Agostino Cuntrera, who had been convicted for his role in the murder of Paolo Violi; Francesco Arcadi, a nearly illiterate hard case who served as Vito’s lieutenant (despite the fact that he was Calabrian) and specialized in bookmaking and drug dealing; Rocco Sollecito, formerly the owner of the Consenza Social Club; and other equally distinguished gentlemen. As police watched, another guest, a fiftyish man wearing glasses, pulled up to the hotel in a Mercedes. His well-coiffed hair was black—unnaturally so for a man his age. Sciammarella and his crew videotaped his entrance. He turned out to be Alfonso Caruana, father of the bride, Francesca Caruana, who was getting hitched to one Anthony Catalanotto.

In June 1996, Inspector Paolo Palazzo of Turin, Italy’s Raggruppamento Operativo Speciale Carabinieri, Sezione Anticrimine (Special Operational Group, Organized Crime Unit) requested Canadian assistance in tracking down Alfonso Caruana and his brothers, whom they suspected of running a vast transnational narcotics trafficking and money-laundering network from their base in Canada. Working with the American DEA, the Italians had amassed information proving that the clan’s operations had continued unabated following the September 1992 expulsion from Venezuela of the Cuntrera brothers, Pasquale, Paolo and Gaspare, and their subsequent arrest in Italy.

Sciammarella’s unit, working with the RCMP, launched its own investigation. They began keeping tabs on various suspects, identified from their video recording of the wedding of Alfonso’s daughter the year before. The Caruanas were doing business in the United States, Italy, South America, Switzerland, France, Germany and Great Britain, but they didn’t travel much themselves. The probe proceeded at a snail’s pace until the Mounties caught a break: a U.S. undercover agent who had infiltrated the underworld in Atlanta, Georgia, told them that a South American broker had approached him about taking delivery of a million dollars in Canada. Finally, the investigators had uncovered money flowing between the Caruanas and their international drug business.

Fifty-year-old Alfonso Caruana was living in a spacious white house rented from his nephew Giuseppe Cuntrera in a newly developed subdivision of Woodbridge. The twenty-five tightly spaced luxury homes stood near an expansive country club, a creek and a protected woodland. Caruana’s two-storey residence at 38 Goldpark Court was far more modest than the posh manor house he had occupied in London’s stockbroker belt during his time in Great Britain, but its well-manicured front lawn and elegantly patterned driveway nonetheless suggested that the tenant had considerable income at his disposal. Alfonso and his wife, Giuseppina Caruana, owned a late-model Volkswagen Golf GTI and a 1994 Toyota Previa, and he soon bought a Cadillac. Alfonso’s younger brother Pasquale, then aged forty-eight, lived in Maple, a twenty-minute drive northeast. Their older brother Gerlando, fifty-three, resided in Rivière-des-Prairies, in east-end Montreal. He had been released from prison in March 1993 after serving one-third of a twenty-year sentence for his role in the plot to smuggle heroin concealed in exotic teak furniture shipped from Thailand via England (see Chapter 6).

In early 1997, Revenue Canada took Alfonso Caruana to Quebec Superior Court in Montreal, challenging his claims of bankruptcy and seeking to convict him for delinquency in paying the thirty million dollars in back taxes, interest and penalties that he owed. The lawyer for the federal tax agency, Chantal Comtois, noted that Caruana was a Canadian citizen but for years had not paid a penny in income tax. She alleged that when he had fled to Venezuela eleven years earlier, it was to evade Revenue Canada’s grasp.

At the bankruptcy hearing, Caruana, represented by defence attorney Vincent Chiara, cast himself in the role of a struggling ordinary working man forced to ask family members for help in making ends meet. He claimed to earn a net salary of about four hundred dollars a week working at a used-car dealership. “I wash cars, I move them around,” he sighed. He said he spent one hundred dollars a month on gas and public transit fares. His wife, Giuseppina, the court was told, worked in a disco. Their combined monthly income was around $3,500, but their rent alone cost them $1,500. The tax collection department was being asked to swallow a real sob story.

Revenue Canada lawyer Comtois was unmoved, and Superior Court Justice Derek Guthrie wasn’t about to fall for the accused’s tale of woe either. Comtois wondered how it was possible that, in a mere eight months, $21 million had passed through the bank account of a family of such modest means.

“The money wasn’t all mine,” Caruana said through an interpreter.

“But $21 million in your name … that’s an awful lot of money, don’t you think?” Comtois asked.

“I did it that way to provide services to others,” was Caruana’s reply. He testified that most of the money belonged to his uncle Pasquale Cuntrera and his brother-in-law, Giuseppe Cuffaro, and that he had personally deposited only $800,000 in the account—money that he claimed he eventually lost in a failed bid to restart a pig farm in Valencia, Venezuela.

The judge wanted to know how the money had wound up in Caruana’s account. “You went back and forth—Venezuela, Montreal, Switzerland?” he asked.

“No, I had it brought to me,” Caruana answered.

“By whom?” a visibly annoyed Justice Guthrie wanted to know.

“By travellers,” Caruana said.

By then frustrated herself, Comtois asked, point-blank: “Are you not the godfather of the Italian Mafia?” The judge ordered the question withdrawn. The Revenue Canada lawyer then brandished a magazine article claiming that the Cuntrera-Caruana clan owned 60 percent of the island of Aruba, just north of Venezuela and Colombia. Holding the magazine out to Caruana, she asked what he thought of the allegation. “If only it were true,” he said.

It was perhaps no longer true as of 1997: under international pressure, the government of the former Dutch colony had expelled members of the family. Prior to that, however, many observers had remarked that the clan wielded considerable economic and political influence in the island nation. In the opening sentences of Thieves’ World: The Threat of the New Global Network of Organized Crime, Claire Sterling wrote:

The world’s first independent mafia state emerged in 1993. The sovereign Caribbean island of Aruba, sixty-nine square miles of emerald hills and golden sand, proved to belong to the Sicilian Mafia in fact if not in name … Aruba was bought and paid for by the most powerful mafia family abroad: the Cuntrera brothers—Paolo and Pasquale—of Siculiana, Sicily, and Caracas, Venezuela, who had amassed a billion dollars of their own in their twenty-five years as kingpins of the mafia’s North American heroin trade.

Comtois asked Caruana if it was true that he once owned 160 square kilometres of land in Venezuela, near the Colombian border. “Everything is false,” he replied. (He wasn’t lying: the federal lawyer had seriously underestimated the area of the land in question. Through front companies, Caruana and his associates had in fact owned some 400,000 hectares in Venezuela, or 4,000 square kilometres.)

Just prior to leaving Montreal for Venezuela in the late 1980s, Caruana and his wife had sold two buildings they owned on Jean-Talon Street, a plot of land in the Pointe-aux-Trembles neighbourhood, and a house in Laval, all for approximately $1.2 million. But where had the money they used to buy those properties come from in the first place? Comtois wanted to know. When she took the stand, a callow Giuseppina Caruana replied that she couldn’t recall.

“Still, the money didn’t just fall from the sky!” the judge exclaimed.

“These were amounts that I brought back a little at a time from Venezuela,” she said.

At the conclusion of the hearing, Justice Guthrie was a hair’s breadth from branding Alfonso and Giuseppina Caruana liars. “I don’t believe a word he said,” he told the court, saying that Caruana “had almost no memory of extraordinarily large sums of money and what he did with [them] … I don’t believe the bankrupt [Caruana] and his wife, whose testimonies were full of holes, hesitations and incomplete explanations, but I must render my judgment based on proof, not suspicions.”

Revenue Canada was therefore unsuccessful in recovering the amounts due. The Caruanas were officially bankrupt. The judge had to be content with ordering the couple to pay $90,000 of the tax bill to the federal government in monthly instalments of $2,500 over a three-year period. Caruana and his wife returned to Toronto. As they exited the courtroom in Montreal, Alfonso could not suppress a smile, while his lawyer, Chiara, answered journalists with a wink when they asked if he was happy with the court’s decision.

If Alfonso Caruana thought his troubles were over, he was sorely mistaken. The RCMP had launched a secret probe, Project Omertà, specifically targeting him and his clan. A key accomplice of the family, a man named Oreste Pagano, had been operating as a Mexico-based middleman between Colombian cocaine sellers and the Cuntrera-Caruanas. Near the conclusion of Project Omertà in 1998, Pagano became an informant and went on to provide very illuminating testimony about the power of the clan and the role played in it by Vito Rizzuto.

A month after he gave his evasive replies to Chantal Comtois and Justice Derek Guthrie at Quebec Superior Court in Montreal, Alfonso Caruana was at Pearson Airport in Toronto, picking up a visitor: Oreste Pagano. Travelling under the alias Cesare Petruzziello, Pagano had boarded a plane in Port of Spain, Trinidad. Caruana drove his guest to his home on Goldpark Court.

Round-the-clock RCMP surveillance teams took turns listening to their headsets, working to decipher the coded language their suspects used on the phone. They were soon convinced that Pagano had a very specific task to perform while in Canada: he would arrange for the delivery of thousands of dollars to the clan’s Colombian cocaine suppliers. He was also heard making several calls to South America to set up cocaine shipments totalling nearly two thousand kilos to Canada and Italy. Police listened as talk revealed plans for a second consignment of five thousand kilos, destination unknown.

One supplier, Juan Carlos Pavo, told Pagano that he had sent two couriers to Canada to pick up the money; they were staying in a Toronto hotel. Giuseppe Caruana entrusted Pagano with two gym bags containing $750,000 in twenty-dollar bills. Pagano headed for a meeting with the couriers to deliver the bags but gave up when he realized he was being tailed by police. He made one more attempt but again noticed he was being followed. He paid the couriers for their trouble, told them to go back to South America and then got back on a plane himself. The aborted exchange was just one minor episode in the long association of Alfonso Caruana and Oreste Pagano.

Pagano was born on July 15, 1938, in Naples. The fact that he was from the mainland normally would not have ingratiated him with the Sicilian Mafia. But he had extensive criminal experience and an outstanding network of contacts that made him indispensable. No doubt he would have found Caruana’s poverty defence at his bankruptcy hearing hilarious: if anyone knew that Caruana was obscenely rich, it was Pagano. And if there was anyone who knew the true meaning of poverty, that person too was Oreste Pagano.

Growing up during the Second World War, he had often gone hungry. His father, an out-of-work electrician, struggled to feed his wife and their children, two daughters and two sons. And with the family’s house near the port of Naples repeatedly suffering damage from Allied bombs, simply surviving was a daily challenge. Pagano’s father tried to earn some money for his family by fashioning cosmetics bags from tortoise shells, but to little avail. “What I remember the most is a very miserable childhood,” Pagano recalled decades later after he eventually decided to confess to police.

At an age when Canadian children normally begin elementary school, the young Oreste was begging for change on the mean streets of Naples. One day he decided he would be better off trying to make a living outside the family home. “I always tried to get away from this poverty,” he said. “And so at the age of eight, nine years old, I started running away from home.” Every time Oreste disappeared, his mother begged the police to go and find him. By age fourteen, he was deemed incorrigible and sent to reform school, where he lived for two years. When he got out, he hightailed it to Rome. One evening, he and a friend were out walking in the capital when a transvestite approached them, offering cash in exchange for sexual favours. The two young ruffians threw the unfortunate man to the ground, beat him up and stole his money. They were eventually arrested, charged with theft and convicted. Pagano was sentenced to four months in prison. During his testimony, he called the episode “the first real disaster of [his] life”—for his criminal record later kept him from getting a legitimate job.

Once freed, he settled in Brescia, a city of about 150,000 halfway between Milan and Venice. There, he married his first wife and got a job selling linens in the street. Finding the earnings from that line of work inadequate, he supplemented his income through activities that tended to be more profitable, though they were hardly commendable: fraud, theft, forgery. Before long he was back behind bars on a weapons charge. That second trip to jail would mark a turning point in his life. “I met a certain Raffaele Cutolo,” he recalled. Cutolo, who had earned the nickname o’ Professòre thanks to his academic way of speaking and passion for teaching up-and-comers the workings of various con games and criminal schemes, was serving a life term for first-degree murder. From his cell, he was working to revive the Camorra, the Neapolitan equivalent of the Mafia. He recruited prospects from among the prison population and had them swear allegiance to his Nuova Camorra Organizzata (NCO), during a ritual that involved extracting a drop of blood from the initiate’s wrist.

Cutolo provided financial assistance to Pagano and his family. The apprentice showed his eternal gratitude by giving his protector a stray spaniel that had been found and cared for by a kind soul. Then, after his release from prison, Pagano sent clothing, food and money to Cutolo’s older sister and loyal accomplice, Rosetta. Nicknamed Occh’egghiaccio (Eyes of Ice), Rosetta was a hardened criminal who once nearly succeeded in blowing up the police headquarters in Naples. She regularly visited her jailed brother, bringing donations from followers on the outside. In 1978, Raffaele escaped from prison. “He calls me to … go to Naples because he wants to talk to me,” Pagano recalled. The fugitive asked if he could hide out at Pagano’s house in Brescia. Pagano enthusiastically obliged. One evening, he told his house guest that he was going out for a while, and went to a gambling den in Milan. Among the players that night were several highly placed men of honour in the Sicilian Mafia, including Alfredo Bono. “That night, it was my unlucky and lucky night,” Pagano said. By early morning, he had soundly beaten Bono at cards. The latter settled the large debt with promissory notes, which Pagano then gave to Cutolo, who was headed back to Naples in secret.

The head of the NCO was discovered and arrested, however. The police also laid their hands on the money drafts, and when they saw that they bore Pagano’s signature, they had proof of his complicity in Cutolo’s escape. Pagano spent another two years behind bars. As soon as he was freed, he resumed his drug dealing—which earned him another ticket to jail. His life became a not-so-merry-go-round of incarceration and freedom. After five years of one jail term had elapsed, just before Christmas 1988, prison authorities granted him a temporary release pass. When he returned home, he was so appalled at the sight of his children’s poverty that he decided against returning to prison. He was going to make big money and get his family out of the poorhouse. They fled overseas. “This is where I really started drug trafficking,” he told his Canadian handlers. “I had never abandoned my family.”

He started slow, shipping a few kilos of cocaine to Italy, first from Spain and eventually from a new home base: Venezuela. In 1991, a Sicilian trafficker, also on the run, introduced Pagano to Alfonso Caruana. Over dinner on Margarita Island, a popular resort destination in Venezuela, Caruana asked him if he had contacts who could help him purchase very large quantities of cocaine. Pagano had the contacts; Caruana had the money—lots of it. It was the beginning of a fruitful friendship. “Finally I could see something good,” Pagano said. “At least now I could get out of poverty.” He knew the Cuntreras and the Caruanas by reputation and correctly described them as one extended family: “They are descendants of the Mafia,” he said in one of his debriefing sessions. “The grandfather [of Alfonso Caruana] was a Mafioso. His father was a Mafioso. The uncles are Mafiosi.”

Pagano retained a measure of nostalgia about his life. During his lengthy sessions with RCMP investigators, he repeatedly said he had been born into an honest family, blaming his criminal existence on an accumulation of unfortunate circumstances. “My father was an honest and humble working man … My mother is a housewife, very honest … No member of my family has ever been in prison … If I were born in Canada, I would never have a charge in my life … The Canadian legislation is very permissive … because before you arrest a person and … put them in prison, you need concrete evidence. That is why I am saying that if I had been born in Canada, I would never have been convicted,” he said.

Pagano achieved his goal: he escaped from poverty. After a few years in the narcotics trade, he was able to display some of the ostentatious symbols of wealth: sparkling gold Rolexes, other very expensive jewellery, million-dollar homes in Latin America, Italy and Florida. He liked gambling, specifically baccarat. (His love for that game, incidentally, led police to crack the code he and his accomplices used when exchanging telephone numbers. It was inspired by the scoring in baccarat, in which the point values of cards in a hand are added up, with the best possible score being nine. Each digit in the coded telephone number had to be subtracted from nine to arrive at the correct digit: two meant seven, six meant three, etc.)

The RCMP kept Pagano on their radar all through Project Omertà. By the spring of 1998, he was working out of the office of a real estate agency that he owned in Cancún, Mexico. He set up a delivery of two hundred kilos of cocaine, to be delivered to his contact in Houston, Texas, while Alfonso Caruana assigned members of his crew in Montreal the task of finding couriers to pick up the powder. At 12:48 P.M. on April 21, the RCMP intercepted a conversation between the two men. Pagano referred to “stuff” that was stashed and couldn’t be moved right away. “We will wait a week and then do it,” he advised Caruana, then asked him how much he had sent. Answer: “1.4 and 250.” Meaning: Can$1.4 million and U.S.$250,000.

Alfonso’s brother Gerlando had the right man for the Houston pickup: Nunzio LaRosa, age fifty. LaRosa hired two young truckers who had experience moving dope across the border: twenty-nine-year-old John Curtis Hill, of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, and thirty-one-year-old Richard Court, from Saint-Laurent, Quebec. The pair travelled by pickup truck to meet him in Houston. LaRosa was given instructions to hide the two hundred keys of blow under a false floor in the truck. But he was nervous and stupid, and anxious for the load to get to Montreal: the operation was running behind schedule. He divvied up the bricks of powder, packed them in eleven large black plastic garbage bags, tossed them pell-mell behind the driver and passenger seats, and threw a sleeping bag over it all. U.S. officers, tipped off by their RCMP co-investigators, were observing the entire scene as it unfolded at a Shamrock service station.

On Saturday, May 16, Hill and Court hopped into the van and set off, while LaRosa and an accomplice, a fifty-one-year-old Montrealer named Marcel Bureau, followed in a second vehicle. An hour out of Houston, northbound on U.S. Route 59, Hill forgot to signal a lane change. It was the moment Texas Department of Public Safety Troopers C.E. Kibble and John Hart were waiting for. They signalled for Hill to pull over. More intelligent men might have seen through the ruse, but the two couriers fell for it. The state troopers searched the vehicle, immediately found the coke and took Hill and Court into custody. But they let LaRosa and Bureau continue on their way: they wanted them to think the bust was simply rotten luck for Hill and Court, not part of a carefully mounted international narcotics investigation. The RCMP tightened its net. Alfonso Caruana knew he was under surveillance; even his neighbours had noticed the unmarked police cars cruising the area over the past few months. The Project Omertà team had finally amassed the evidence they needed to take down the Caruana clan: a seized cargo of cocaine and several hundred hours of electronic surveillance, during which the suspects discussed exchanges of money and narcotics. They planned mass arrests, to take place at dawn on July 15.

Some eighty police officers were marshalled in Montreal; another fifty in Toronto. Two RCMP officers flew to Mexico City. The Canadian investigators asked their Mexican counterparts to arrest Oreste Pagano on July 15, which happened to be his birthday. For some reason, they didn’t wait until the appointed hour—7 A.M. EDT—to move in: dozens of armed officers broke down the door to Oreste’s house around two in the morning.

“Oreste, Oreste, how are you? Happy birthday!” was one officer’s greeting, just after a bleary-eyed Pagano awoke to the sight of police cars surrounding his house and the sound of helicopter blades thwacking the night air overhead. Along with his son-in-law, Alberto Minelli, whose job was to launder the profits of their drug trafficking, he was handcuffed, whisked to a military prison, photographed and then taken to a small airport. There the two were put on a small plane bound for Mexico City, and transferred to Toronto on board a Gulfstream jet crammed with soldiers.

The Mexican pilot decided to fly over the United States without making a refuelling stop, and the Gulfstream penetrated Canadian airspace much sooner than expected. Having received no flight plan, air traffic controllers were surprised when the pilot radioed for authorization to land. Official recordings captured the confusion in the control tower: “Where the hell did this Mexican military plane come from?” one air traffic controller is heard saying to a colleague. He then asks the pilot: “What are you doing in this airspace? Please identify yourself.”

Apparently, this was the spicy Mexican recipe for getting rid of undesirables. The Canadian style was, as usual, bland by comparison. Officers rang doorbells, held up arrest warrants and ushered the offenders into the rear seats of patrol cars. Nine were pinched in Montreal and Toronto, including Alfonso Caruana, his brothers, Gerlando and Pasquale, and a nephew, Giovanni.

“These arrests were the culmination of a two-year investigation which has effectively dismantled an alleged Mafia family, the Cuntrera-Caruana group,” RCMP Inspector Ben Soave, head of the CFSEU, said emphatically. Press conference descriptions of the scope of police operations are often embellished, but in this case, Soave’s words were not hyperbole. Italy’s carabinieri had put the Cuntreras behind bars; now the Mounties and other Canadian police had netted the Caruanas.

Officers searched Alfonso Caruana’s house and found $40,000 in cash along with jewellery worth $304,229 hidden in a secret compartment. They also inspected the office of Giuseppe Cuntrera (son of the late Liborio Cuntrera) in Toronto and discovered a suitcase hidden in the drop ceiling. It contained $200,000 in twenty-dollar bills. Oreste Pagano would later confirm that this money was partial payment for a further shipment of coke, yet to be delivered. The police next paid a visit to the office of a second Giuseppe Cuntrera, son of Paolo. The keys to two safes attracted their attention. When they opened the strongboxes, they found more than Can$390,000 and more than U.S.$11,000, along with jewellery and collectible coins worth in excess of $310,000.

Three months later, in October 1998, Venezuelan authorities seized some 400,000 hectares of land in the state of Bolívar, six apartments, a dozen luxury automobiles, two yachts, and the contents of several bank accounts, totalling U.S.$14 million. In the Greater Toronto Area, the RCMP identified eleven buildings and eighteen businesses linked to the Cuntrera-Caruana clan. They included a gym, a nightclub, a restaurant, a supermarket, a tanning salon, a car wash, a pool hall, a travel agency, a meat-packing plant, a hotel management company and an import-export firm, along with several shell companies—holdings and numbered companies with no actual operations, used exclusively for money laundering. Millions of dollars per year had transited through the account of one company that officially reported annual sales of less than ten thousand dollars.

At the time of their arrests, Alfonso Caruana was preparing to return to Venezuela, while his brother Gerlando was setting up a holding company to muddy the traces of money earned legally and illegally in Montreal. He hoped one day to settle quietly with his girlfriend in Belize, in Central America. While awaiting their trial on drug trafficking and money-laundering charges, Oreste Pagano, Alfonso Caruana and the members of their organization swelled the ranks of the boarders at the Toronto East Detention Centre. Pagano may have been a high-ranking member of the Neapolitan Camorra, but that didn’t equate to credentials in the eyes of the higher-ups in the Sicilian Mafia. He was not one of them. He had served the Caruanas well, but now he was of no further use. The Caruanas owed him a lot of money—some of it for a five-hundred-kilo cocaine shipment that had made it to its destination in Montreal—but refused to pay him. Pagano didn’t even have enough money to hire a lawyer: his assets, though scattered throughout several countries, had all been seized.

One day, as inmates stretched their legs in the prison’s exercise yard, Pagano walked up to Alfonso Caruana, who proceeded to act as though his former associate didn’t even exist. It was this humiliating snub that sparked Pagano’s decision to turn state’s evidence. He sent a message to prison authorities that he wanted to talk to the police. The first debriefing took place at the detention centre. Pagano dangled a carrot: he was ready to spill information that would not only furnish investigators with extra evidence against the Caruanas but also provide proof of the involvement of other ringleaders, including the Rizzutos. In return, he wanted a lot: a new identity, secure relocation for him and his family, return of the money and property that had been confiscated by the Mexican police, freedom for his girlfriend, who was currently imprisoned in Venezuela, and an escort to help her get out of the country, among other things. Pagano was transferred to another correctional facility. Negotiations dragged on for months, and lawyers for the Canadian government eventually made some concessions. They attempted to recover two million dollars that Pagano had kept in a safe at his home in Cancún, but the money had “disappeared” on the night of his arrest. In the end, the turncoat was given money so that he could hire a lawyer.

Once a satisfactory deal was reached, Pagano made a lengthy confession, documented in twenty-six hours of videotaped declarations. An initial session took place in July 1998 at a Travelodge hotel in Sudbury, Ontario, far from the eyes and ears of underworld acquaintances. Pagano confirmed that in 1991, after meeting Alfonso Caruana on the Venezuelan island of Margarita, he had set up eight cocaine shipments. Asking his handlers for a pen and paper, he jotted down several figures and added them up—the total amount of coke had been 3,500 kilos, he informed the police. Shipments to Canada always went through Montreal, often by sea but sometimes by truck. The street value of the cocaine was between thirty thousand and fifty thousand dollars per kilo. Some deliveries failed. Shipments were sometimes seized by police; this had happened in Puerto Cabello, Venezuela, and Houston, Texas. Such were the risks of the trade, Pagano said. But, he added, the profits were far greater than the losses.

Pagano told his police handlers that Alfonso Caruana paid him $28,000 per kilo of coke at the time. Picking up the pen again, he calculated that Caruana must have earned around $36 million thanks to him. He arrived at that total by subtracting his commission and the amount paid to the Colombian wholesalers. Caruana, he explained, had never revealed to him how much he made from trafficking: “He never told me exactly … Nor would I ever ask him, because I think that these questions are a bit intrusive between people.”

Pagano explained that cocaine deliveries picked up again, and even increased in frequency, after the two hundred kilos were seized near Houston in May 1998. A few weeks later—on June 3, to be precise—a boat loaded with five hundred kilos of the white powder left Venezuela bound for Montreal. A man Pagano identified only as Yvon, who claimed to be a legitimate businessman running a trout farm, was to take delivery of the shipment on his sailboat. From Cancún, Pagano had to make calls to make sure the cargo had arrived safely in Montreal.

By July 14, Pagano still had no news. “I called the lawyer, Chiara, to know whether something had happened to Alfonso,” he told investigators. “Chiara [said] that nothing had happened. Therefore, I asked for the telephone number of Gerlando [Caruana] and I called him. I asked him if everything was fine, if Alfonso was fine and if the goods had arrived. He told me that the goods had arrived … Then, the same night, I was arrested.”

Montreal was only the North American drop-off point for the coke that the Caruanas bought; they also made regular deliveries to Europe. The head of Project Omertà, RCMP Inspector Ben Soave, estimated that the clan moved between two and three hundred kilos to various locations every three weeks. In Italy, the group had previously been linked to shipments totalling eleven tonnes. Members of the clan were not particularly upset if the odd shipment fell into police hands; in one conversation overheard by investigators, they described the loss of the two hundred kilos that had left Houston as “the price of doing business,” Soave explained. “That loss of six million dollars [the estimated value of the cocaine] took part of maybe a couple of minutes in the conversation and then they went on to the other shipments they had lined up. Well, six million dollars would break a lot of businesses in Canada, and for them it was the subject of a few minutes’ discussion. I’m sure they had concerns about what went wrong, but, you know, life went on.”

“If organized crime were a hockey game, Mr. Caruana would be [Wayne] Gretzky,” Soave concluded.

Pagano next met with police, accompanied this time by a federal government prosecutor, on September 21, 1999. The location was Room 925 of the Embassy Suites Hotel in Markham, near Toronto. Pagano explained how he had spent time with the Cuntrera brothers in Venezuela, before their arrest and extradition to Italy, as well as with Alfonso Caruana, before his return to Canada. Back then, the clan often hid cocaine shipments in barrels of tar, and frequent deliveries were made to Genoa, Italy.

Finding sources of the drug was never a problem; big-time Colombian exporters numbered in the hundreds. Most had ties to revolutionaries and guerrilla groups, Pagano said, adding: “I wanted to explain to you … the trafficking of drugs will never end.” He ridiculed the U.S. “war on drugs” and similar efforts by Western countries, saying that the millions sent to the governments of Colombia and Peru to stem the northward flow of narcotics were regularly siphoned off, and that cocaine production in those countries had doubled in recent years despite the increased aid. “All the money that is sent to these governments is only used to buy arms,” he said.

It would be only a matter of time before everyone learned that he was talking to the police, Pagano nervously predicted. Former business contacts would then be lining up to murder him. “I have many enemies that want to kill me,” he said. “They would like to cut me up to little pieces … I need security for me and my children.”

With Alfonso Caruana now in prison, a successor would surely be named to head the Cuntrera-Caruana clan. Who would be the one to make that decision? Pagano’s handlers wanted to know. He reminded them that, as a Neapolitan, he was seen as an outcast. “That [decision] would be made in Sicily,” he surmised. “I wouldn’t know. They are Sicilian; I am not Sicilian.”

“You have to be Sicilian to know these secrets?” one of the interrogators asked.

“Exactly,” Pagano replied.

On November 18, 1999, Pagano was questioned again at the Embassy Suites Hotel. During this session he revealed how Alfonso Caruana and Vito Rizzuto had felt betrayed by senior Venezuelan government officials whom they had bribed but who had failed to help them.

Alfonso Caruana had become infuriated, Pagano said, after Venezuelan authorities arrested the three Cuntrera brothers, seizing hotels they owned and opening their safety deposit boxes. Clan members believed they had been the victims of a plot: Alfonso was convinced the Americans were behind it all and had paid off the Venezuelans to bust the Cuntreras. He quoted a Sicilian proverb: “Whoever has money and friendship can screw justice.”

Alfonso Caruana had gone so far as to contemplate assassinating the Venezuelan interior minister, the informant revealed. But he decided the best strategy was to save his own skin. “Not long after that, Alfonso left the city [Caracas] and came here to Canada … He feels very safe in Canada … He knows that being a Canadian citizen, after his release, he will be free in every aspect,” Pagano explained. Caruana had told him that in the worst-case scenario, he would spend no more than five years in prison. “He says, ‘Even if [I] get twenty-five years of jail, which is the maximum imprisonment … I only serve five years.’ ”

Caruana was half right. In February 2000, trapped by Pagano’s duplicity and thousands of pages of transcribed phone conversations, he pleaded guilty in Ontario Superior Court to charges of importing and trafficking in narcotics. He was sentenced to eighteen years—a term that was commuted to three years, to end in April 2003. But he was never able to enjoy so much as a second of freedom. Ontario police kept Alfonso in custody, citing an international arrest warrant that called for his extradition to Italy, where he had been convicted in absentia by a Palermo court. The sentence was severe: twenty-two years’ imprisonment for his role in importing massive amounts of cocaine.

Caruana fought the extradition order as long as he could. In November 2004, a lower court ruled that he should be deported to Italy. The Mafioso took his case to the Ontario Court of Appeal, which upheld the ruling. The Supreme Court of Canada then refused to allow a final appeal request, and Caruana was extradited on January 29, 2008. His brothers, Gerlando and Pasquale, were sentenced in Canada to jail terms of eighteen and ten years respectively. Oreste Pagano pleaded guilty to several charges on December 7, 1999, and was immediately sent to Italy—where, in return for his collaboration with authorities, he received a payment of $100,000, protection for his family, and assurances that he would be taken into the national witness protection program. On November 17, 2004, interrogated by Italian investigators, he described his relations with Vito Rizzuto in detail.

“I know Vito Rizzuto, and I had the chance to work with him in the 1990s,” he said. “In particular I can tell you that I heard about him in Venezuela, while I was staying at the Hotel Royal, owned by Pasquale Cuntrera. Umberto Naviglia pointed to Vito and told me that he was the boss of the Mafia in Canada, linked with the Sicilian Mafia … In 1993, Alfonso Caruana introduced me to [him]. The meeting took place in a hotel in Montreal where Caruana and I were staying. Rizzuto joined us in the afternoon after a golf game. At the time, I had a Venezuelan passport with a fake identity; my name was Cesare Petruzziello. I learned at that time that Vito was an avid golf player.”

Pagano went on, explaining how he subsequently met Vito at the wedding of Alfonso Caruana’s daughter, in Toronto: “At that time, Vito proposed the first deal in relation to the importation of cocaine into Canada, from Venezuela, through a man that he trusted. This guy was a Canadian and he owned a mine in Venezuela. I practically had to deliver the cocaine to him … That importation was successful, and I knew because I was involved in that deal. I knew that the deal was coordinated by Vito Rizzuto.”

Every month, the owner of the Venezuelan mine, which was located in the state of Bolívar, shipped minerals to Canada for processing. Pagano used this connection to send an initial one-hundred-kilogram load of cocaine. Other shipments followed.

“Also in the 1990s, Vito Rizzuto asked me the favour to arrange the murder of a Venezuelan lawyer,” Pagano revealed. “The lawyer defended his father [after the 1988 cocaine possession charge] and asked for $500,000 in legal fees, with the promise that he would be acquitted, and released right away, but he failed and his father was convicted … At that time, I was living in Venezuela, but I didn’t feel I could carry that out. I tried to find a reason to postpone it, but I could not do that without compromising my relationship with Vito Rizzuto, because not to comply could create serious and dangerous consequences for me. I tried to postpone, tried to find excuses.

“Then at the end of 1994, we organized another importation for five hundred kilos, using the same channels. That importation didn’t go well. The drugs were seized in Venezuela. Many people were arrested, including the son of the owner of the gold mine … After the seizure I expressed my disappointment to Vito, but he told me he would find out if anyone had made a mistake. Not only would he pay, but he would also bring me the head of the person responsible on a plate. Then he paid part of my investment.

“So I met him again a few months later, when his son Nicolò Jr. got married [on June 3, 1995],” Pagano continued. “I attended the wedding with Alfonso Caruana and his wife. At the wedding, I saw someone that I recognized. I asked Alfonso, ‘Who is that guy?’ He told me that it was Salvatore Scotto,* the representative of the Bono family in Italy. He was wanted for the murder of a police officer and his pregnant wife, but he came to Canada to pay the respect of [that] major Sicilian Mafia family to Rizzuto … The wedding was attended by almost six hundred people. There were representatives of New York and Sicilian families, but I didn’t ask for their names.”

Pagano took advantage of the wedding to huddle with Vito Rizzuto and map out a massive cocaine importing scheme. The Montreal godfather said he wanted to bring in up to ten thousand kilos. Pagano’s job would be to get the drugs onto a Canadian ship departing from Venezuela. Once in international waters, the cargo would be transferred from the mother ship to a second vessel. “In that case, the second boat avoided customs,” Pagano explained to the Italian investigators.

As part of his earlier videotaped statements in Canada, Pagano had told RCMP officers about the symbiotic relationship between the Rizzuto and Caruana clans: “When I met Vito, I realized that he trusted the two [Caruana] brothers. I had the impression that they were all part of the same organization … They are neither rivals nor competitors because many times they would work together … I know that Vito Rizzuto was the boss of the Mafia in Canada … [He] is a kind of manager … He utilizes people who don’t belong to his family to do the dirty work. In Italy, everything is done within the organization. They don’t use outside people.”

One month prior to the arrest of Oreste Pagano, an event occurred that may have seemed relatively trivial but in fact spoke volumes about Vito Rizzuto’s “manager” role as well as his ascendancy over a significant swath of the Montreal underworld, not just members of the Mafia. In a manner befitting his godfather role, Vito was a keen arbitrator of conflicts.

Monday, June 15, 1998, was shaping up to be a slow news day in Montreal’s Palais de Justice: the courthouse corridors were practically deserted, and none of the trials in progress seemed worthy of attention. Journalists were chatting about what they’d done on the weekend and sharing jokes with lawyers. On a whim, a reporter for La Presse went up to Room 3.08, where a preliminary hearing was being held for an Ontario drug trafficker named Glen Cameron. The odds of the writer getting enough material for a story seemed slim: the case had been subjected to a publication ban. He took a few notes, then slipped his notebook into his back pocket and stepped back out into the hallway. A ripple of commotion spread around the third floor: there was Vito Rizzuto, exiting a small conference room used by lawyers and clients. He leaned against the wall, speaking in hushed tones with his lawyer, Jean Salois.

The reporter called a photographer, who rushed over. The don gracing the courthouse with his presence was a rare sight indeed. The photographer clicked away, shooting one picture after another, his camera’s motor drive whirring. Rizzuto ducked behind his lawyer in a vain attempt to evade the lens. Then, growing annoyed, he buttonholed the two men from La Presse. “Seems to me you’ve taken enough pictures,” he said in English, his tone firm but polite.

It turned out Rizzuto had been called by the prosecution to testify at Cameron’s preliminary hearing. His testimony was postponed, however. Eleven days later, on June 26, Vito stood in the witness box in Room 3.08.

Cameron was accused of having laundered three million dollars in drug money. He was an independent trafficker who supplied hashish oil to the Rock Machine biker gang in Montreal, as well as to criminal bikers in Kingston, Sudbury and Toronto—territories coveted by the Hells Angels.

At the start of the so-called Biker War in 1994, the Hells Angels had warned Cameron to stop dealing with their rivals, the Rock Machine. He basically told them to take a hike. This was, obviously, an unwise tactic. Their second warning came in the form of a machine-gun attack. Cameron was hit in the leg, an injury that would leave him with a permanent limp. The assailant then pointed the barrel of his weapon at Cameron’s temple. “Why are you doing this to me?” Cameron croaked, sweating from every pore. Nine months later, he had resumed supplying hash oil to customers on both sides of the Biker War. A few years later, a Montreal police officer told him that the Hells Angels were still out to get him.

Cameron went to Vito Rizzuto, asking him to intercede with Maurice “Mom” Boucher, leader of the Nomads, the Hells Angels’ elite club in Quebec. He offered the Mafia chieftain at least fifty thousand dollars in exchange for his arbitration services. Rizzuto acknowledged in court that he had met with Cameron on two occasions at a seafood restaurant in the Marché de La Tour shopping centre, in Saint-Léonard. He said he had agreed to get involved as a favour to a friend, Juan Ramón Fernández.

Fernández, a loyal Rizzuto soldier, had first met Cameron in prison, when the latter approached him in the company of another trafficker from his organization, Luis Lopes. Subsequently, relying on contacts outside, Fernández had helped Cameron and Lopes import hash oil from Jamaica.

At their first meeting, Rizzuto conversed with Cameron and two acquaintances in the rear of the seafood restaurant, then huddled alone with Cameron for ten minutes or so. “Cameron, he told me … that he would do anything … if I could fix things,” Vito told the judge. As the meeting wrapped up, the godfather said, “Let me see what I can do for you.” At a second meeting, Vito explained that he had met with the Hells Angels and that Cameron had nothing more to fear from them.

A police search of Cameron’s house in the small town of Glenroy, Ontario, had turned up a datebook for 1997. Cameron had written, on two pages, the number “50,000” and the word “Vito.” Under questioning by the lawyer for the prosecution, Rizzuto admitted that Cameron had wanted to pay him for his mediation services, but he had refused to accept any money. His version of the story was that he told Cameron he “didn’t want anything,” but urged Cameron to do a favour for Fernández if ever the opportunity came up.

By 2000, there were clear signs that the Nomads had gained the upper hand in their bloody conflict with the Rock Machine. Vito Rizzuto, naturally, had aligned with the side that looked set to emerge victorious. In the past, he had been content to work with Mom Boucher on an ad hoc basis; now, he moved to make their partnership a formal one. In April, he delegated his son Nicolò to hold a series of exploratory meetings with Normand Robitaille, a member of the Nomads and a trusted associate of Mom Boucher. The goal was to mark out cocaine distribution territories and set a wholesale price for the drug on the Montreal market.

The negotiations took place in secret; rank-and-file members of both the Nomads and the Sicilian Mafia knew nothing about them. Some Mafia drug dealers eventually learned of the meetings, but kept on doing business with the Rock Machine anyway. One of them was Salvatore Gervasi, a hulking thirty-one-year-old. His father, Paolo Gervasi, was an old-school Mafioso who had consorted with the Rizzutos for years and owned the Castel Tina strip club in Saint-Léonard, where Vito kept an upstairs office. The doormen allowed Rock Machine members into the club, despite the patches they overtly displayed on their leather jackets and vests. The bikers even had a permanently reserved table.

Salvatore Gervasi’s main contacts in the Rock Machine were the paunchy Tony Plescio—held in high esteem by the elder Gervasi as well—and members of the Dark Circle, considered the biker club’s elite death squad. Vito and his lieutenant Francesco Arcadi repeatedly asked Paolo Gervasi to tell his son to stop dealing with Rock Machine members.

If Paolo did, the warnings went unheeded.

On April 20, 2000, Salvatore Gervasi was shot in the neck and killed. The assassins wrapped a plastic bag around his head, then loosely rolled his body up in a tarp and stuffed it into the trunk of his Porsche, which they left near the corner of Couture and Belmont Streets in Saint-Léonard—not far from the victim’s parents’ home, his last known address. Passersby found it odd that the expensive sports car was sitting there with its sunroof open, and alerted police. Investigators called it a “clean hit”; in other words, it bore the hallmarks of a Mafia murder.

A grieving Paolo Gervasi, obsessed with finding his son’s killers, met with Vito Rizzuto on a number of occasions, hired a private detective, and travelled to Italy looking for clues. He reportedly offered $400,000 to whoever could finger the killers, and compiled a blacklist of twelve likely suspects. Then, in a rage, he ordered his own club, the Castel Tina, bulldozed.

Gervasi and Francesco Arcadi met in a restaurant, but police were unable to ascertain what was said. Days later, on August 14, 2000, a man approached Gervasi as he left a bank on Jean-Talon Street. He spoke to him briefly, then pulled out a gun and shot him. Seriously wounded, Gervasi was taken to hospital.

Two days later, Arcadi conferred with Vito Rizzuto in the alleyway behind the Consenza club in Saint-Léonard. Police found a way to eavesdrop but were only able to capture snatches of the conversation. “There’s only one way, a bullet to the head,” one of the Mafiosi said. Had they decided it was time to liquidate Gervasi? No one can say for certain.

At any rate, a bomb was rigged to explode under Gervasi’s Jeep Cherokee on February 25, 2002. Police got an anonymous tip about a suspicious package beneath the vehicle, which was parked in front of the Consenza. The charge consisted of a dozen sticks of explosives—Magnafrac, to be precise—connected to a remote-control receiver. Had the device gone off, it could have left a very messy scene indeed: the Consenza was in the middle of a small strip mall. Police immediately evacuated businesses and residences within a wide perimeter. Staff at a nearby daycare centre hustled children onto a hastily requisitioned school bus: as soon as the door shut, the driver sped the kids away.

There would be no further warnings or failed attempts on the life of Paolo Gervasi. On January 19, 2004, he had just walked out of a Jean-Talon Street pastry shop and got behind the wheel of his Jeep when a man approached the vehicle and opened fire. The bullets shattered the side window and tore into Gervasi, killing him instantly. He was sixty-two years old and had spent the last four years of his life searching for the men who had murdered his son.

In June 2000, the preparatory negotiations between Nick Rizzuto Jr. and Normand Robitaille were deemed successful, and a meeting was scheduled to finalize a deal with the Hells Angels. Vito decided to attend in person. He was accompanied by three other Mafiosi, including Tony Mucci (infamous as the man who had walked into the newsroom of the daily newspaper Le Devoir on May 1, 1973, and shot three times at journalist Jean-Pierre Charbonneau, wounding him in the arm). The summit was held at the Tops Resto-bar, owned by real-estate magnate Antonio (Tony) Accurso. Normand Robitaille headed the biker delegation, seconded by Michel Rose and André Chouinard. Mom Boucher called Chouinard to say he was on his way but, for reasons unknown, he never showed up.

The Sicilians and the Hells Angels agreed to fix the wholesale price of cocaine at fifty thousand dollars a kilo, the highest in Canada—and anywhere in the Americas, for that matter. They also decided how to split up distribution on the Island of Montreal: the Mafia could sell the drug in the city’s north and northeast ends: in Saint-Léonard, Anjou and Rivière-des-Prairies, as well as the Little Italy district. They also retained their distribution monopoly in the bars and clubs on lower Saint-Laurent Boulevard, Crescent Street and other tony downtown spots. All the rest was decreed to be Hells Angels turf. At first glance, it looked like a significant concession by the Mafia. In reality, they gave up very little, since their specialty was bulk sales and not street-level retail distribution. It was a savvy move on Vito’s part: he was assured of the Hells Angels’ support in enforcing the outrageous hike in the price of cocaine, which would only swell the profits from traffic in the drug.

There were other meetings. On July 17 and 31, 2000, thirty-three-year-old Nick Jr. and an associate, Miguel Torres, discussed cocaine deals with Robitaille in an Italian restaurant on Saint-Laurent Boulevard. That summer, an average of 250 kilos of coke was being dealt in Montreal every week. Investigators, though, had a front-row seat from which to track the traffickers’ moves: Robitaille’s bodyguard, Dany Kane, was an informant. Kane was very active and privy to all manner of conversations, which he regularly recorded for the benefit of police. At the end of one exchange, Robitaille told Kane that the Italians were very powerful, “and that if they were at war with them, the Hells Angels would have more trouble with them than they had with the Rock Machine.” Robitaille was also impressed by Vito Rizzuto’s sense of fair play, telling Kane, “He’s an okay guy.”

Not surprisingly, the new arrangement worsened tensions between the rival biker gangs. The leaders of the Rock Machine, founded fifteen years earlier by Salvatore Cazzetta, were not pleased that they’d been frozen out of the deal. Their violent conflict with the Hells Angels had flared up in July 1994 and would last until June 2002, resulting in more than 160 deaths in Quebec, including several innocent bystanders. In 1995, an eleven-year-old boy, Daniel Desrochers, was killed by a shard of metal from a vehicle that exploded outside a biker hangout on Adam Street in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, a working-class neighbourhood in east Montreal. The tragedy sparked public fury and led to the creation by the RCMP, the SQ and Montreal police of a crack anti-biker unit dubbed Carcajou (Wolverine). Two prison guards, Diane Lavigne and Pierre Rondeau, were shot and killed in 1997. On August 26, 1999, Serge Hervieux, a father of two, was shot to death at his place of work, a garage in Saint-Léonard, by an assailant wielding a .357 Magnum. The killer had mistaken Hervieux for a co-worker with the same first name: Serge Bruneau, a major cocaine supplier for the Rock Machine.

On July 7, 2000, Hélène Brunet, a thirty-one-year-old waitress, was gravely wounded in a shooting at a café in Montreal’s north end. She was serving breakfast to two Hells Angels members when a pair of masked men burst in and opened fire. One of the Angels used Brunet as a human shield; the other was shot dead. Then on September 13, 2000, veteran crime reporter Michel Auger was shot several times in the parking lot of his newspaper, Le Journal de Montréal. He survived, but the attempt on his life spurred a further wave of public anger. Police forces in Quebec ramped up efforts to put the bikers out of commission.

On the one hand, the situation was to the Sicilian Mafia’s advantage. Police lacked the resources to fight crime on all fronts and, as long as their energies were channelled into hunting down the biker gangs, they couldn’t clamp down as firmly on Italian organized crime. On the other hand, public pressure in reaction to the Biker War eventually prompted the federal government to toughen up its anti-gang legislation, putting criminal groups of all stripes at greater risk of prosecution. Police were given broader powers and, whenever convicted individuals could be linked to organized crime, they faced stiffer jail sentences. Vito Rizzuto and other influential members of the Montreal mob decided it was time to put a stop to the violence.

Analysts including Guy Ouellette, of the SQ, and Jean-Pierre Lévesque, with Criminal Intelligence Service Canada (CISC), are fairly sure the Mafia played a role in peace talks between the Hells Angels and Rock Machine. On September 26, 2000, three weeks after the attempted murder of Journal reporter Auger, Mom Boucher met up with the leader of the Rock Machine, Fred Faucher, in a room at the Quebec City courthouse. A peace deal was cemented on October 8 at Bleu Marin, an Italian restaurant on Crescent Street in downtown Montreal. A photographer for crime tabloid Allô Police got a message on his pager: Would he come down to the restaurant and capture the moment for posterity? It was a good marketing coup: the photos of the rival biker “brothers” formalizing their truce, surrounded by assorted henchmen, caused a sensation.

“Rather than suffer the consequences, the representatives of the various organized crime families exerted pressure to ensure they would reach an understanding,” CISC’S Lévesque commented. “The first to speak up were the heads of the Italian Mafia … The bikers up against the Italian Mafia; that’s a bit like comparing Marty McSorley to Mario Lemieux,” he said. (McSorley, a tough-guy defenceman then with the Boston Bruins, was being tried in criminal court and would eventually be convicted of assault with a weapon for striking an opponent with his stick, while the Pittsburgh Penguins’ Lemieux, a gentleman player and superstar, had by then been inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame.)

If the bikers were consciously rolling out a public-relations campaign, it soon fizzled. On October 10, Mom Boucher was arrested: the Quebec Court of Appeal had ordered a new trial in the case of murdered prison guards Lavigne and Rondeau. Then on December 6, Fred Faucher and fourteen members of the Rock Machine, who had just “patched over” to the Bandidos—a powerful bike gang with clubs in the United States and Europe—were packed off to prison as well. And police were readying even bigger arrests. But in the meantime, blood continued to be spilled. The truce was clearly a sham.

Three members of the Rowdy Crew, a gang affiliated with the Hells Angels, attacked one Francis Laforest in front of his home in broad daylight, beating the twenty-nine-year-old man to death with baseball bats. Three weeks earlier, Laforest had refused to let the bikers sell drugs in his bar in Terrebonne, an off-island suburb northeast of Montreal.

The December 2000 amalgamation of the Rock Machine into the Bandidos gave the latter group a beachhead in Ontario. The Hells Angels responded by absorbing the members of most other clubs in the province—Satan’s Choice, Last Chance, the Lobos and the Para-Dice Riders—as well as a handful of dissident Rock Machine and Outlaws members. At a ceremony held on December 29 in Sorel, Quebec, 179 Ontario bikers became full-patch Hells Angels, and eleven others were accepted as prospects.

Ontario had emerged as a new battleground. Canada’s richest and most populous province represented a huge market for narcotics sales and all manner of other rackets.

It was a prize toward which Montreal’s Sicilian Mafia, ruled by the iron hand of Vito Rizzuto, next turned its attention.

* Scotto was arrested by Italian police in 2001, after eight years on the run, and received a life sentence for his role in the 1992 Palermo car bombing that killed anti-Mafia judge Paolo Borsellino and his five-man bodyguard detail.

The seventeenth-century Chiesa Madre (Mother Church) with its single bell tower overlooking Cattolica Eraclea.

Perched on a low hill, Cattolica Eraclea was once a prosperous farming community.

Nicolò Rizzuto lived in this house before he immigrated to Montreal in 1954 with his wife and two children.

The home of Antonino Manno, grandfather of Nicolò Rizzuto.

Few vehicles travel the quiet, narrow streets of Cattolica Eraclea.

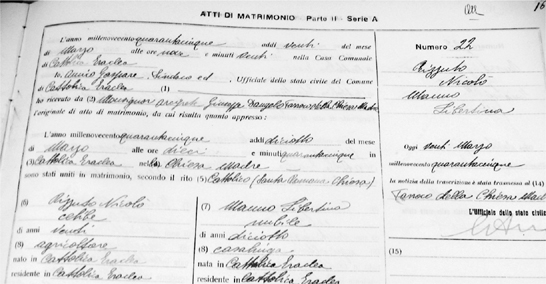

Nicolò Rizzuto and Libertina Manno married in 1945. He was twenty-one years old; she was eighteen.

The couple’s marriage certificate, found in the archives of Cattolica Eraclea.

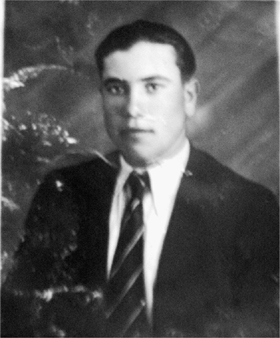

Nicolò Rizzuto had just turned thirty when he arrived in Montreal.

November 26, 1966: The wedding of Vito Rizzuto and Giovanna Cammalleri in Toronto. Nicolò and Libertina stand with their son and his bride.

The wedding of Maria Rizzuto and Paolo Renda (at right) in Montreal. Left, Giovanna and Vito Rizzuto; middle, Libertina and Nicolò Rizzuto.

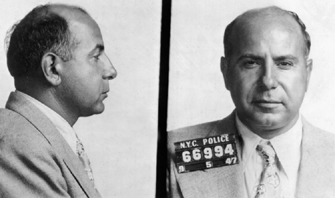

NYPD mugshots of Carmine “Lilo” Galante.

November 28, 1966: Salvatore “Bill” Bonanno (second from left) and five other U.S. Mafiosi are arrested in Montreal; police seize four handguns from their cars. At far left is Luigi Greco, the Sicilian clan’s representative in the Cotroni crime family.

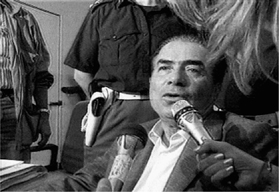

Paolo Violi at the time of the CECO hearings, at which he refused to testify.

Giuseppe “Joe” LoPresti.

February 22, 1978: Paolo Violi lies slain on the floor of the Bar Jean-Talon (formerly the Reggio Bar). (photo credit col2.1)

Agostino Cuntrera (left) and Domenico Manno, two of the three men who pleaded guilty to conspiracy to murder Paolo Violi.

November 16, 1980: Vito Rizzuto and his wife, Giovanna, attend the lavish reception after the wedding of Mafia kingpin Giuseppe Bono in Manhattan.

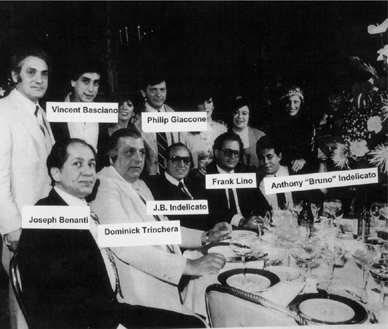

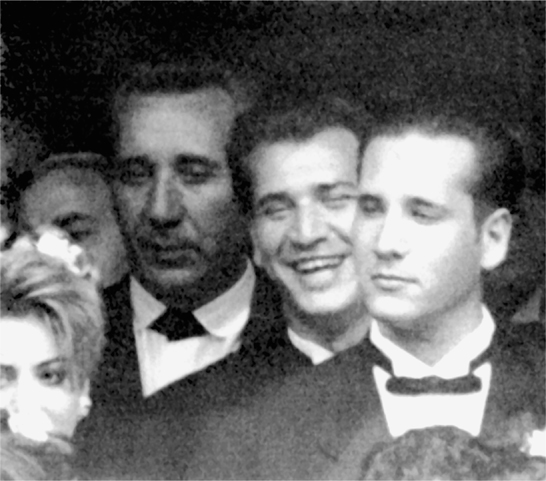

Also attending the Bono wedding reception, mere months before they would be murdered, were renegade Bonanno family capos Philip “Philly Lucky” Giaccone, Dominick “Big Trin” Trinchera and Anthony “Sonny Red” Indelicato.

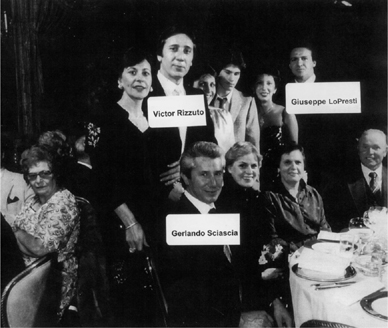

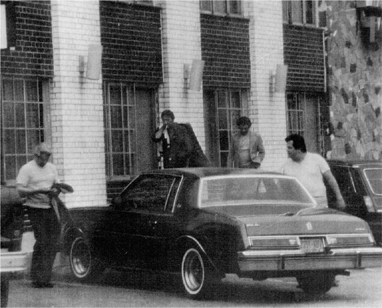

May 6, 1981: The day after the murder of the three capos, Vito Rizzuto and Gerlando Sciascia are photographed by police as they leave the Capri Motor Lodge in the Bronx. With them are Bonanno family associates Joseph Massino and Giovanni Ligammari.

Italian judge Giovanni Falcone, whose investigations brought him on occasion to Canada. The 1992 assassination of the anti-Mafia crusader caused a public outcry in Italy.

Falcone died in the white car seen at right, shattered by a bomb hidden in a highway culvert outside Palermo, on May 23, 1992. His wife and three of their bodyguards were also killed in the attack, blamed on the Mafia.

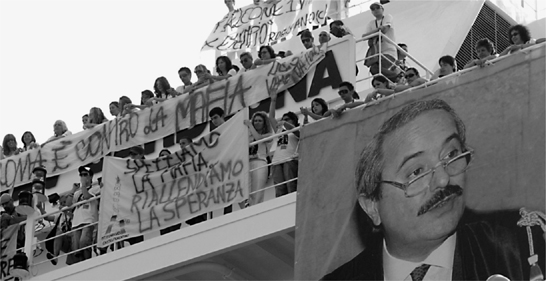

Outraged citizens unfurl banners following the murder of Giovanni Falcone. (photo credit col2.2)

Vincenzo “Vic” Cotroni.

Luigi Greco.

Frank Cotroni.

Frank Cotroni, seen here with Paolo (Paul), the second of his five sons, who would be murdered in 1998 in the driveway of his Repentigny, Quebec, home.

Lawyers Vincenzo Vecchio, Richard Judd and Joseph Lagana were frequent customers at the currency exchange covertly operated by the RCMP in downtown Montreal from 1990 to 1994.

Christian Deschênes, a close associate of the Sicilian clan, was arrested while attempting to recover a huge shipment of Colombian cocaine flown into a remote airstrip in Quebec.

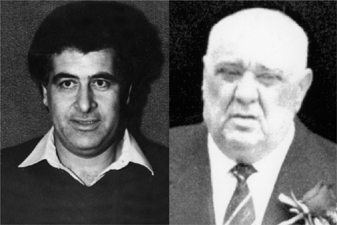

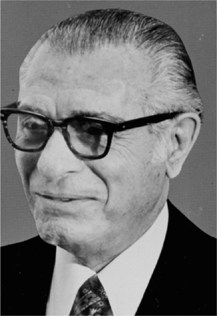

Pasquale Cuntrera.

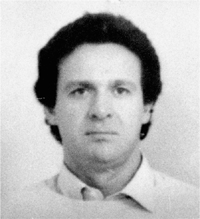

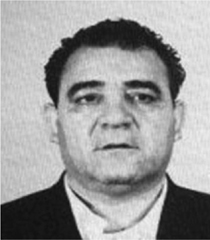

Pasquale Caruana.

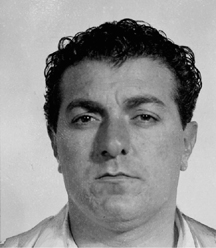

Gerlando Caruana.

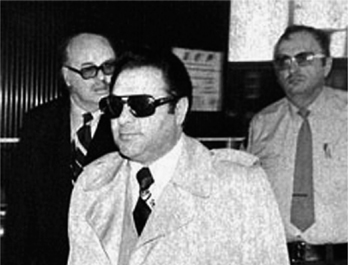

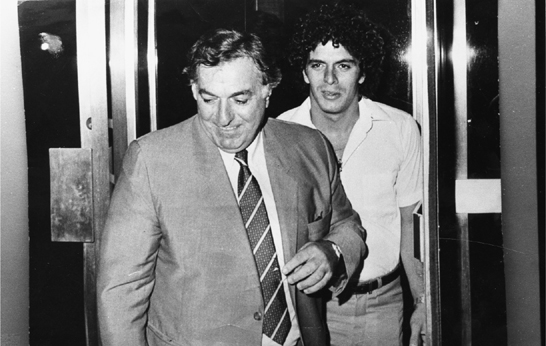

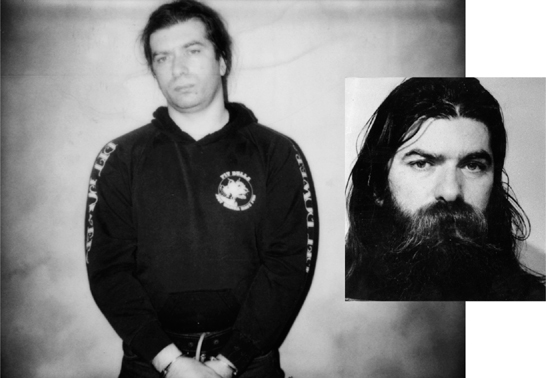

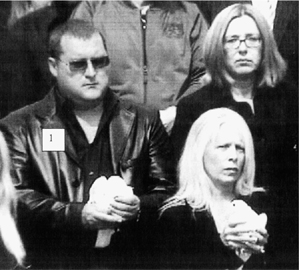

April 29, 1995: Alfonso Caruana, his hair dyed black, is seen in stills from police surveillance video of the wedding of his daughter in Toronto.

Two views of Salvatore Cazzetta, former head of the Rock Machine biker gang and one of the most influential figures in Montreal organized crime.

Normand Marvin “Casper” Ouimet and Mario Brouillette, two members of the latter-day “business-oriented” incarnation of Quebec’s Hells Angels.

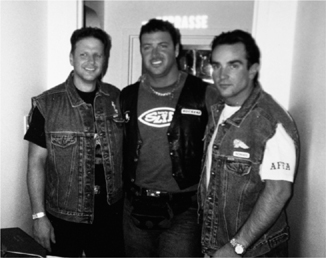

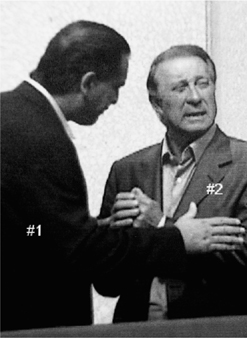

October 8, 2000: The Hells Angels and the Rock Machine cement their truce at Bleu Marin restaurant in downtown Montreal. (photo credit col2.3)

Normand Robitaille (foreground), of the Hells Angels Nomads, negotiated the wholesale price of cocaine with the Montreal Mafia in the summer of 2000.

Outlaw bikers André Chouinard, Jean-Guy Bourgouin and Normand Robitaille were all arrested and convicted in the wake of Operation Springtime 2001.

Happier times before the fall: Vito Rizzuto with his elder son, Nicolò (Nick) Jr., and his younger, Leonardo. Nick would be murdered in December 2009.

The remains of Philip Giaccone and Dominick Trinchera, two of the three murdered Bonanno capos, were found in 2004 in Ozone Park, New York, not far from the spot where, twenty-three years earlier, a group of children had stumbled upon the still-fresh corpse of Anthony Indelicato. The discovery would prove a key step in the extradition of Vito Rizzuto to the US and his later incarceration in a Colorado prison. (photo credit col2.4)

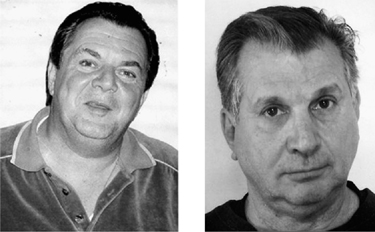

The men who betrayed Vito Rizzuto: Joseph “Big Joey” Massino (left), head of the Bonanno family, and his right-hand man (and brother-in-law), Salvatore “Good-Looking Sal” Vitale.

August 17, 2006: after the final appeal to block his extradition to the United States is denied, Vito Rizzuto is led under heavy police escort to Montréal-Trudeau Airport, where he will board an FBI jet.

Domenico Macri, a rising star in the Sicilian clan ranks, was shot to death in August 2005.

One Sicilian clan associate particularly upset by the murder of Macri, whom he viewed as a brother, was Francesco Del Balso.

The killing of Nick Rizzuto Jr. (left) and the kidnapping of Paolo Renda (right) were severe blows against the Rizzuto family. The two are seen here at the funeral of Domenico Macri.

Calogero “Charlie” Renda (bottom left), his father, Paolo (middle right), and Rocco Sollecito (middle, with dark glasses) at the Macri funeral.

Four frames from police video surveillance of the Consenza Social Club on Montreal’s Jarry Street. Between February 2, 2004, and August 31, 2006, carefully concealed cameras recorded 192 separate transactions in the backroom of the club. Men brought in bundles of cash in plastics bags or boxes; the bills were then counted on a round table and divided into stacks, destined for the Sicilian clan’s top five leaders: Nicolò Rizzuto and his son, Vito, Paolo Renda, Rocco Sollecito and Francesco Arcadi.

The exterior of the Consenza Social Club, which served as the Montreal Mafia’s de facto headquarters for at least thirty years.

Nicolò Rizzuto in his final years.

Vito Rizzuto.

Rocco Sollecito.

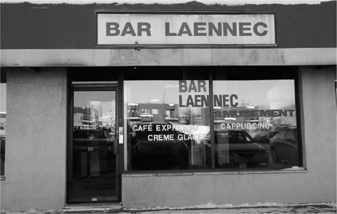

The Bar Laennec in Laval, which became the hangout for the new generation of Mafia from the Rizzuto-Arcadi clan.

Lorenzo “Skunk” Giordano.

Francesco Arcadi.

The final blow: a single bullet hole in the kitchen window of Nicolò Rizzuto’s home on Antoine Berthelet Avenue in Montreal, from the shot that killed the clan’s patriarch on November 10, 2010. (photo credit col2.5)