Brick by brick: How LEGO Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry - BusinessNews Publishing (2014)

Part I. The Seven Truths of Innovation and the LEGO Group’s Decline

Chapter 2. Boosting Innovation

The LEGO Group’s Bold Bid to Keep Pace with a Fast-Forward World

Our goal, for the LEGO brand to be the strongest among families with children, is within our grasp.

—LEGO Annual Accounts, 1999

THE LEGO VP’S ANGRY RETORT HUNG IN THE AIR LIKE acrid cigar smoke: “Over my dead body will LEGO ever introduce Star Wars.”

It was early 1997, and Peter Eio, chief of the company’s operations in the Americas, had just proposed to the LEGO Group’s senior management team a collaboration that he’d been working on for months: that the company partner with Lucasfilm Ltd. to bring out a licensed line of LEGO Star Wars toys. The line would accompany the first installment of the long-awaited Star Wars prequel trilogy, which was coming out in the spring of 1999. Executives at Lucas loved LEGO and had long wanted to partner with the company. Executives in Billund were aghast. Eio had to struggle to keep his composure.

“Normally the Danes are very polite people,” recalled Eio. “We never had huge confrontations. But their initial reaction to Star Wars was one of shock and horror that we would even suggest such a thing. It wasn’t the LEGO way.”

Star Wars skeptics had a point. In the four decades since the birth of the brick, LEGO had always gone its own way, eschewing partnerships and licensing agreements. It succeeded at almost every turn. Year after year, the company’s master toy makers had unerringly divined what kids wanted next. Wheels, minifigs, trains, themed kits such as Space and Castle—for years, the LEGO Group’s ever-expanding range fueled steadily surging sales. For proud, self-sufficient LEGO, the notion that it should license another outfit’s intellectual property, even if the partner was an unstoppable hit maker such as Lucasfilm, was repugnant. So was the fact that if LEGO licensed Star Wars, it would have to play by Hollywood’s rules. “It was almost as if LEGO didn’t trust outside partners,” said Eio. “The thinking was always, ‘We’ll do it ourselves. We can do it better.’ ”

Aside from the go-it-alone culture that pervaded Billund, the biggest obstacle to a Lucasfilm/LEGO licensing deal was the prospect of introducing attack cruisers, assassin droids, and other Star Wars armaments into the LEGO Group’s milieu. Even today, LEGO continues to embrace one of founder Ole Kirk Christiansen’s core values: to never let war seem like child’s play. LEGO executives who opposed the deal feared that by aligning the company’s squeaky-clean reputation with the Star Wars brand, it might well diminish its own. “The very name, Star Wars, was anathema to the LEGO concept,” Eio asserted. “It was just so horrid to them that we’d even consider linking with a brand that was all about battle.”

Despite resistance from LEGO managers, Eio believed that his battle—to persuade the company to marry the brick with the Force—was one he had to win. For Eio, the most compelling reason to do a deal with Lucasfilm was the danger of not doing one.

From his base at the LEGO Group’s North American headquarters in Enfield, Connecticut, Eio was alarmed at how the United States was becoming a license-driven market at a far faster rate than Europe. Hit movies and TV cartoon series were spinning off countless licensed products, from Buzz Lightyear to Transformers, accounting for half of all toys sold in the United States. Heavyweight rivals Hasbro and Mattel were bulking up on licensing pacts with Disney and others, while LEGO hadn’t deigned to get into the game. Eio feared that if LEGO didn’t tap into the global pop culture phenomenon that was Star Wars, the future would catch it out and it would remain a licensing laggard.

Working with Howard Roffman, Lucasfilm’s licensing chief, Eio launched an internal campaign to convince the LEGO Group’s brain trust that Star Wars was more Ivanhoe than G.I. Joe—that despite its sci-fi trappings, the series presented a classic confrontation between good and evil, with little blood and no guts. Eio also suggested a proposal so sensible that no one could assail it: why not ask the parents? And so they did. LEGO surveyed parents in the United States and Germany to learn whether they’d say yes to a marriage between LEGO and Star Wars. U.S. parents overwhelmingly backed the idea; surprisingly, so did German parents, who at that time were the company’s largest and by far its most conservative market.

Despite the approval of most surveyed parents, some LEGO executives still refused to countenance Star Wars. In the end, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, who was an ardent Star Wars fan and was buoyed by the polling, overruled his tradition-bound executives and gave the deal his imprimatur. And so launched one of the most successful and enduring partnerships in the toy industry’s history. Released on the wings of the blockbuster The Phantom Menace, LEGO Star Wars was a staggering hit, accounting for more than one-sixth of the company’s sales.

And yet, even at the very moment that Eio and his allies won the skirmish over Star Wars, sweeping changes in its competitive landscape put LEGO in grave peril of losing the wider war. The battle for Star Wars would prove to be just the first of several consequential debates that were boiling up within LEGO, as the company confronted an increasingly disruptive world and a toy industry that was becoming more volatile with each passing year.

The LEGO Star Wars X-Wing Starfighter.

For decades, the LEGO Group’s proven ability to twine education with imagination and creativity with fun gave it a near monopoly over the market for construction-based toys. Year after year, LEGO sets jumped off the toy shop shelves and the profits poured into the corporate coffers. In the 1990s, however, the brick’s fairy-tale story began to lose its luster.

The first challenge to the brick maker’s growth streak actually arose in 1988, with the expiration of the last of the LEGO Group’s patents for its interlocking brick. After that, any company could produce a plastic brick that was compatible with LEGO bricks, so long as it didn’t use the LEGO logo. As a result, the LEGO Group’s long-standing monopoly on its stud-and-tube brick quickly fractured, giving rise to competitive anarchy. A throng of upstart, low-cost competitors—Mega Bloks from Canada, Cobi SA from Poland, Oxford Bricks from China, and many more—flooded the market with cheap knockoffs of bricks and minifigs that could snap onto LEGO sets. LEGO punched back with a flurry of lawsuits, arguing that although the patent had expired, the design of the LEGO brick was so ubiquitous, any other company’s production of it violated trademark law. In every country where LEGO employed the strategy, it ultimately lost.

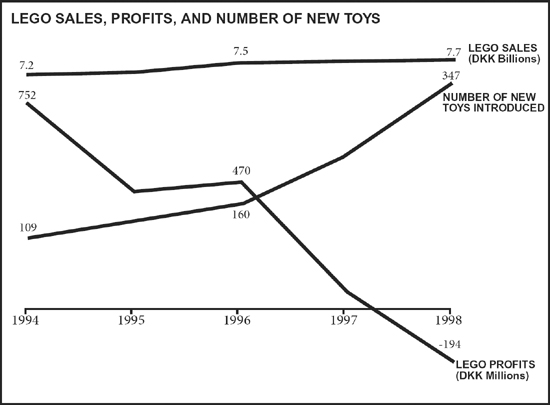

A second setback was one of the LEGO Group’s own making. In 1993, the toy maker’s remarkable fifteen-year stretch of double-digit growth had stalled out. The company’s capacity to grow sales and expand into new markets with its long-standing portfolio had seemingly run its natural course. LEGO couldn’t sustain double-digit sales increases by making incremental improvements to its existing product lineup. To keep climbing, LEGO had to build a new, powerful set of growth engines.

When sales growth stopped, the toy maker responded by going on a development binge, dramatically boosting the number of products in its portfolio. In theory, that was a good thing: experimentation is the prelude to real progress. By launching lots of products, LEGO was bound to come up with a hit. Problem was, the LEGO Group’s once-famous discipline eroded as quickly as its products proliferated. From 1994 to 1998, LEGO tripled the number of new toys it produced, introducing an average of five major new product themes each year. The result was a whole lot of busyness but very little good business. Expensive new product lines such as the Primo line for babies; the Znap line with its new, more flexible plastic; the aforementioned Scala line of Barbie-like dolls; and a CyberMaster robotics kit were all outright failures. Production costs soared but sales plateaued, increasing by a measly 5 percent over four years.

The company’s most vexing challenge was to catch up with a world that was rapidly leaving it behind. By the late 1990s, interactive games and kid-centered software gained a mesmerizing grip on great swaths of the brick’s core consumers. Addictive games such as Sim City and RollerCoaster Tycoon were wildly adept at replicating a building experience in an online world. And digital special effects made the fantasy worlds of movies come alive like never before. Compared to the razzle-dazzle of Game Boy and Xbox, Jurassic Park and Nintendo, the humble brick seemed like a relic from a bygone era.

Equally challenging was the fact that the day-to-day lives of middle-class children had grown remarkably time-compressed and programmed, leaving far fewer hours for the LEGO style of open-ended, self-guided play. And kids were growing out of traditional toys far faster than they used to. The London Independent captured the tenor of the times when it opined in a December 2000 article on LEGO: “Today’s instant gratification child does not want to go through the bother of constructing something with several hundred plastic bricks, when a virtual pet comes to life with a stroke of its back.”8

Those rapidly accelerating forces—a mob of new entrants eager to exploit the LEGO Group’s old-guard legacy costs; the revolutionary changes in kids’ lives; and an increasingly desperate bid to kick out dozens of new products in the hopes that something, anything might goose sales—combined to knock LEGO out of its aerie near the top of the toy industry. In 1998, Billund reported that LEGO had gone $48 million into the red. It was the first loss in the LEGO Group’s history, prompting a layoff of more than one thousand people in the first half of 1999, by far the company’s largest. Both bitter blows provided further evidence that LEGO was suddenly in a fight for relevance.

LEGO found itself confronting a future-defining challenge: how could its philosophy of free-form, creative play compete in a media-driven entertainment economy where the linear, story-driven experiences of computer games and TV shows reigned supreme?

The LEGO Group’s bid to answer that question began with a series of decisive moves. In October 1998, as the losses mounted, Kristiansen brought in Poul Plougmann, a turnaround expert and former chief operating officer of Bang & Olufsen, the Danish maker of high-quality home-electronics equipment, to take over the company’s day-to-day management. An avid hunter, art enthusiast, and Francophile who lived with his wife in Paris (he would commute to Billund), Plougmann was a somewhat reclusive executive who shared his thoughts and plans with just a few close confidants. Because he played a lead role in reviving Bang & Olufsen, a Danish national treasure, the Danish press hailed him as a “miracle man” when he arrived at LEGO. In a remarkable concession, Kristiansen stepped aside, though he retained his title as president of the company and renewed his focus on developing toys. In an effort to stanch the bleeding, Plougmann, who was given the title of finance director (he was later promoted to chief operating officer), formulated and initiated the mass layoffs of early 1999. But LEGO was not about to hunker down and retrench. Plougmann was promised a hefty bonus if he doubled the LEGO Group’s sales by 2005. He was recruited and incentivized to grow LEGO out of its malaise.

Plougmann joined LEGO at what were arguably among the worst and best moments in its modern history. The company would soon endure its first-ever large-scale downsizing, the discordantly titled Fitness Plan, which resulted in the aforementioned firing of one-tenth of the company’s workforce. At the same time, LEGO was just beginning to glimpse the market’s lust for LEGO Star Wars, whose first year’s sales exceeded the company’s initial forecast by 500 percent. Emboldened by the stratospheric results of Star Wars and the enduring strength of the LEGO brand—which, despite the company’s recent travails, was still embraced by more than 70 percent of households with children in Western countries—Plougmann and his team embarked on an ambitious initiative for reigniting growth. The effort was oriented around seven of the business world’s most popular strategies for developing new products and services. In fact, they’re now so pervasive they’ve become a kind of gospel: the seven truths of innovation.

Hire diverse and creative people.

Head for blue-ocean markets.

Be customer driven.

Practice disruptive innovation.

Foster open innovation—heed the wisdom of the crowd.

Explore the full spectrum of innovation.

Build an innovation culture.

Many of the business world’s best and brightest minds have extolled at least one of these principles for boosting innovation; many of the world’s most admired companies have championed them.

✵ Procter & Gamble opened up its innovation efforts through its Connect + Develop initiative, through which it formed more than one thousand successful agreements with top innovators from around the world. At one point, innovators who worked outside P&G’s walls contributed to more than half of the company’s new product initiatives.

✵ Quicken and Southwest Airlines redefined their industries largely because they sailed to blue-ocean markets, which competitors ignored.

✵ Canon’s digital cameras disrupted and all but destroyed the film camera market.

✵ Apple sustained its chokehold on the MP3 music player market largely because it surrounded the iPod with a full spectrum of complementary innovations: the iTunes music service with its game-changing 99¢-per-song business model; its extensive catalog of docks, skins, chargers, and other accessories; and its iconic branding campaign.

Faced with the challenge of doubling the LEGO Group’s sales by 2005, Plougmann and his lieutenants refocused the company’s developers on the seven truths of innovation and challenged them to surpass such giants as McDonald’s and Coca-Cola and become “the world’s strongest brand among families with children.” Although LEGO never explicitly called these innovation strategies the “seven truths,” it pursued them nonetheless.

Here’s what LEGO did. In the next chapter, we’ll reveal how it all turned out.

Hire diverse and creative people. Modern management strategists have long proclaimed that heterogeneity fuels creativity—company cultures that are marked by a potent mix of varied experiences and work styles yield better ideas, execute those ideas better, and even develop people better. Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab, has gone even further, declaring that the surest way to tap into a wellspring of new ideas “is to make sure that each person in your organization is as different as possible from the others. Under these conditions, and only these conditions, will people maintain varied perspectives and demonstrate their knowledge in different ways.”9

When Plougmann joined LEGO, he found a work culture that was isolated and calcifying—its mostly male, very veteran Danish executives and designers were hamstrung by a lack of urgency and by homogenized thinking. “Product development was in the hands of people who’d been at LEGO for twenty or thirty years,” he recalled. “They were so inward looking, they expected that whatever they created would be right for the market.” He also concluded the company had hit the limit in terms of the talent it could attract to the LEGO Group’s remote, rainy hometown. If LEGO were to reenergize product development and appeal to the world’s plethora of ethnic groups and play experiences, it would have to break out of Billund.

In very short order, LEGO lured top talent from beyond Denmark and expanded its links to the outside world. The company purchased Zowie Intertainment, a San Mateo, California-based maker of technology-driven education toys, which gave LEGO a close-up look at new ventures emerging out of Silicon Valley. To build out its gaming and Internet offerings, LEGO hired a development outfit outside London and set up another in New York. It created a toys-for-tots design outpost in Milan. And it strove to scope out new toy trends by establishing a network of LEGO designers located in Tokyo, Barcelona, Munich, and Los Angeles. Instead of trying to bring world-class design talent to Billund, LEGO essentially brought Billund to the talent.

Plougmann injected more fresh thinking into the company’s product development group by recruiting a former Bang & Olufsen colleague, an Italian executive named Francesco Ciccolella, to reimagine LEGO toys and remake the LEGO brand. Ciccolella and his brand development team sought nothing less than the total transformation of LEGO from a toy to an idea, declaring that the company “will build businesses wherever our idea can be translated into unique concepts.” He also issued the brand statement “Play On,” which drew on the English translation of the LEGO name, “play well.” No doubt the “Play On” slogan reflected the company’s desire to keep kids playing with bricks—and buying bricks—through childhood and beyond. Writing in the new LEGO branding manual, Ciccolella’s image makers decreed, “PLAY ON is the ultimate expression of the LEGO brand.”

One product line that was not, in Ciccolella’s view, an encapsulation of the LEGO brand was DUPLO. In two of the toy maker’s largest markets, Germany and the Netherlands, DUPLO was nearly as big a brand as LEGO. But DUPLO was far less of a presence in the United States, where LEGO executives were unnerved by the sudden rise of electronic educational toys from companies such as LeapFrog, which would soon bound past LEGO to (temporarily) become the third-largest toy maker in the toy world’s largest market. Recalled veteran DUPLO designer Allan Steen Larsen, “There was a real fear that electronic toys were taking over from physical, traditional toys.”

Seeking to build a bigger American beachhead with higher-priced electronic toys, Ciccolella’s team played down the DUPLO brand of starter bricks and largely replaced it with a radically different line, dubbed LEGO Explore, which they branded as a “complete discovery system from birth to school age.” Featuring creations such as the Explore Music Roller (see insert photo 5), an electronic pull toy that chirped singsongy tunes while a toddler towed it, Ciccolella’s design team hid the brick—which would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier—and fashioned a brand of toys whose look and feel were far more akin to Fisher-Price than to LEGO.

The logic behind launching Explore, explained Plougmann, was to “make the single brick less important in the minds of mothers. What mattered was the skill and knowledge that the [Explore] system could bring to their children.” Of all the diverse, wide-ranging ideas to come out of the company’s new cast of creatives, Explore would prove to be one of the most daring, un-LEGO-like lines that LEGO had ever imagined.

Head for blue-ocean markets. For more than a decade, business thinkers such as W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, the authors of Blue Ocean Strategy, have exhorted companies to push beyond the tactic of making incremental improvements to existing products and instead swim for the open water of untapped market spaces. If red oceans are the crowded, bloodied waters where companies chew each other up for smaller and smaller chunks of market share, blue oceans are vast markets, unsullied by cutthroat competition, where outsize profits await. The LEGO Explore toys were an attempt to discover a blue ocean in the toddler toy market by producing electronic educational toys under the LEGO brand.

In another blue-ocean move, LEGO leaped from toys to education. The company’s first foray into the education market actually goes back to 1950, when it created sets of large LEGO bricks for kindergarten classrooms. In the late 1990s, LEGO conceived a strategy of moving from education products to services. The market for after-school education in Japan and South Korea was booming. (A typical South Korean child could attend as many as two or three after-school programs each day.) LEGO bet the market was ripe for an entirely new type of learning experience, with LEGO bricks at its core.

LEGO partnered with a South Korean company, Learning Tool, to develop a series of programs that used bricks and other LEGO elements to teach science, technology, engineering, and math to kids. The idea was to help kids solve problems through hands-on building; one lesson, for example, used LEGO gears to teach ratios. LEGO lent the initiative its brand, helped develop the curriculum, trained personnel, and developed special kits for the LEGO Education Centers. Here was an entirely uncontested market for LEGO. Launched in 2001, the centers got off to a promising start, and within three years South Korea alone featured 140 LEGO Education Centers.

On the product side, LEGO headed for Hollywood. Having hauled in a treasure chest of record sales by licensing Star Wars from George Lucas, the LEGO Group’s brain trust concluded that another maker of Hollywood blockbusters, Steven Spielberg, could steer it to a new, unbounded blue ocean. But rather than license a hot Spielberg property, LEGO licensed the Spielberg name. It created a product that had never been offered to kids: a buildable “movie studio in a box” for creating LEGO animations. The kit consisted of a collection of minifigs and LEGO pieces for building a movie set; a motion-detecting digital camera in a LEGO casing; and software for editing. Taken together, the awkwardly titled LEGO & Steven Spielberg MovieMaker set (see insert photo 4) gave kids the ability to make movies that captured the play scenes they’d been acting out in their heads.

“There was nothing out there where kids could build their own model and make a movie out of it,” asserted John Sahlertz, who led the MovieMaker development team. “It was a completely new category for toys.”

In a clever twist on blue-ocean strategy, LEGO aimed not only to stake out uncontested market space with the Spielberg kits but also to entice kids to clamor for more traditional sets such as LEGO Pirates, by using the camera and software from the Spielberg set to make piratethemed movies. Thus, Spielberg MovieMaker would catalyze sales for LEGO Pirates and other classic lines. If the strategy succeeded, the Spielberg MovieMaker—a category-defining, blue-ocean creation—would clear the water for red-ocean stalwarts such as LEGO Pirates.

Be customer driven. There’s hardly a modern business strategist who doesn’t contend that successful brand builders are so inquisitive about their customers’ lives and so attuned to their desires, they can’t help but put the customer’s point of view above all else. And LEGO was as good as any company at seeing through the eyes of an inventive seven-year-old boy. But soon after Plougmann’s arrival, LEGO sought to grow its sales by appealing to a different customer.

After a team of outside consultants produced surveys showing two-thirds of children in Western households were moving to electronics and discarding traditional toys at an earlier age, Plougmann and his deputies concluded that LEGO should take a decisive turn. Rather than redouble its efforts to become the top toy maker for the smaller slice of kids who loved to build, LEGO opted to pursue the larger population of kids who didn’t. The effort’s essence would later be captured in Ciccolella’s revised brand manual, which shockingly declared that the company’s “greatest strength,” the LEGO brick, “is our biggest limitation.”

As always, LEGO aimed to remain customer driven. But suddenly, an entirely different set of customers—kids who desired a faster form of gratification and were deemed to be less skilled at building with bricks—was doing the driving. “There was a lot of concern that children couldn’t build anymore,” recalled Niels Milan Pedersen, a longtime LEGO freelance designer. “It was thought that American children, in particular, couldn’t build as well as they did in the eighties. We were told the kits had to be very basic.”

The LEGO Group’s developers knew that simpler sets, by themselves, lacked the magnetism to pull in the media-saturated kids of the late 1990s. But what would? Flush with the success of LEGO Star Wars, developers doubled down on the notion that in Star Wars, kids were drawn to something that LEGO had never before delivered: a rich, theme-driven world where kids could play out their fantasies. LEGO Star Wars and, later, the LEGO Group’s line of Harry Potter-themed sets put an exclamation point on the notion that in a world where movies, television, and the Internet shape so much of today’s play, storytelling matters.

Seeking to combine a compelling narrative with a seamless building experience, a team of LEGO designers set about crafting a character-driven toy line oriented around an easy-to-build action figure. They began by fabricating a set of cube-shaped bricks that could be snapped into a humanoid figure that was 30 percent larger than the minifig. They called their new set Cubic.

“The whole idea was to get it down to where a five-year-old could easily build with it,” said Jan Ryan, who led the Cubic design team. “And then we had the idea that he was going to be a kind of hero.”

Mindful of the need to create a toy that would kick up a craze among American boys, the Cubic team gave itself a design challenge: what is the LEGO version of a very American toy hero, G.I. Joe? Over many months, they sculpted a set of muscles onto the Cubic figure, outfitted it in a quasi-military flight suit, and gave it a plucky, quintessentially American name, Jack Stone. In this bad-guy-battling boy hero, kids confronted an entirely different kind of LEGO experience—darker and edgier, with a fast-paced story line that had him piloting Res-Q copters and foiling bank robbers. LEGO bet that Jack Stone would attract swarms of new customers who desired kits that were less buildable but more playable. So confident was LEGO of Jack Stone’s potential that designers began to suspect the character would do the unthinkable: supplant the iconic minifig.

“They wanted to [replace] the minifig and put in this Jack Stone figure,” said Pedersen, who helped design Jack Stone. “We were told from the top that the minifig wasn’t considered cool.”

The Jack Stone “minifigure” (right) and a classic LEGO minifigure. Unlike the classic minifigure, the Jack Stone figure could not be disassembled.

Practice disruptive innovation. In his book The Innovator’s Dilemma, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen introduced his theory of disruptive innovation, which he defined as a less pricey product or service, initially designed for less-demanding customers, which catches on and captures its market, displacing the incumbents.10 Christensen saw how low-quality, low-cost technologies were ramping up faster than ever before. Unburdened by the legacy costs and organizational inertia of more mature competitors, these new technologies quickly replaced established technologies and destroyed the incumbents’ core markets. Technologies such as digital photography and computer disk drives started out as low-end alternatives to their pricier counterparts; industry incumbents felt little pressure to respond. But those technologies quickly improved and eventually revolutionized their industries. Believing video game makers such as Nintendo would further roil the markets for traditional toys, LEGO bet that it could do some disrupting of its own with a project called Darwin.

The seeds for Darwin were planted on an autumn day in 1994, when a Swiss man showed up unexpectedly at the LEGO Group’s Billund headquarters and asked to speak to Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen. Clad in knickers, with shoulder-length hair and a beard that flowed down to his chest, the man carried a four-minute video clip featuring computer-generated LEGO spaceships blazing across the heavens. He introduced himself as Dent-de-Lion du Midi, otherwise known as “Dandi” (pronounced “Dondee”). He didn’t get to see the LEGO Group’s president, but he did talk his way into a meeting with two technicians from the company’s audiovisual department.

Dandi showed the two men his clip, whose 3-D modeling far surpassed anything LEGO had in the works. And he presented a plan to transform LEGO bricks into digital bits. He proposed creating a database of high-quality, digitized renderings of the thousands of pieces in the LEGO Group’s product portfolio—bricks, wheels, minifigs, rods, gears, and beyond. Once completed, the database would give any LEGO design team the capacity to quickly create digital versions of physical kits, as well as 3-D LEGO cartoons, films, building instructions, television ads, and other marketing collateral. Dandi’s presentation was so convincing, he won a meeting with LEGO executives, who concluded that such a database might propel LEGO to the forefront of the market for computer-animated play experiences. In May 1995, Dandi and a small band of software programmers set to work on the Darwin project.

Darwin was a massively ambitious venture that required an enormous start-up investment, both to build the LEGO 3-D database, dubbed L3-D, and develop commercial opportunities for L3-D and digital technology. LEGO recruited alpha software coders and 3-D computer graphics wizards from across Europe and the United States to the Darwin project, which eventually grew to include more than 120 people. And LEGO armed them with the largest installation of Silicon Graphics supercomputers in northern Europe.

Although the task of creating a computerized LEGO construction system was loaded with technological challenges, the Darwin project’s risks were somewhat leavened by the fact that software development trends were moving in the LEGO Group’s direction. Bjarne Tveskov, who led Darwin’s software team, was one among several commentators who noted that the move toward object-oriented programming, where applications could be fashioned out of small, predefined blocks of code, was a lot like building with LEGO. Tveskov recalled how the Darwin team took enormous inspiration from the author Douglas Coupland. In his epistolary novel Microserfs, Coupland described LEGO as “a potent three-dimensional modeling tool and a language in itself.”11 Coupland later told a Danish television interviewer that if LEGO played its cards right, it would be the Microsoft of the twenty-first century. (In the 1990s, that was considered a soaring compliment.)

For a time, it seemed as if Coupland’s heady prediction had a whiff of truth to it. In 1996, the Darwin team wowed the crowd at SIG-GRAPH, the world’s largest computer graphics conference, with a virtual-reality demo of a LEGO-ized version of the gathering’s host city, New Orleans. Participants explored a fully immersive, virtual New Orleans made of 3-D LEGO bricks and populated with digitized minifigs. Afterward, an overjoyed group of Darwinites gathered with LEGO execs for dinner. “Kjeld stood up and told us, ‘You people are the future of the company,’ ” remembered Tveskov. “And we totally believed him.”

Foster open innovation—heed the wisdom of the crowd. During the first years of the past decade, the heaving growth of massive online communities inspired books such as Open Innovation, Wikinomics, and The Wisdom of Crowds, which showed how creative companies were harnessing the collective genius of virtual communities to spur innovation and growth. LEGO, a conservative company whose numerous battles over patent infringements had made it hyperprotective of its intellectual property, certainly did not rush into the crowdsourcing craze. But LEGO did take some tentative first steps.

For much of its history, LEGO was a monolith—a massively intractable organization that viewed its fans solely as consumers, never as cocreators. The company’s mostly Danish designers believed that when it came to conjuring the next cycle of brick-based construction toys, they were the smartest guys in the room. And who could argue with them? Their creations, from the minifig to battery-powered trains to enduring themes such as Space and Castle, had fueled the LEGO Group’s double-digit growth for the better part of two decades.

By the mid-1990s, however, the Internet gave rise to fan-created sites such as LUGNET.com, which let LEGO enthusiasts from around the globe chat, link to one another’s personal sites, and even inventory all of the pieces and sets LEGO had ever made. Most tellingly, such sites let fans share online photos and videos of their strikingly clever “MOCs,” otherwise known as “My Own Creations,” which offered tangible evidence that not even the LEGO Group’s most talented designers could consistently outinnovate the millions of LEGO fanatics from across the globe. The creative output of its sprawling, online community of independent brick masters convinced LEGO to give crowdsourcing a modest test.

In mid-2000, LEGO commissioned a software development outfit to begin work on the LEGO Digital Designer, a computer-aided design program that let enthusiasts build their own dream models using virtual 3-D bricks (see insert photo 6). The company’s strategy was to let fans use the Designer software (which was based on the Darwin project’s technology) to create virtual models and upload them to a LEGO website, which would eventually come to be called LEGO Factory. LEGO would then manufacture the custom-designed, physical sets and ship them to consumers. Thus, LEGO enabled people to create their own kits—designing them, shaping them—according to their own individual desires. If other fans liked the custom-designed sets, they too could order them.

An early exemplar of this strategy was the LEGO Blacksmith Shop, created by a fan named Daniel Siskind. A designer living in Minneapolis, Siskind had launched Brickmania.com, an independent site offering brick-based kits that sometimes featured subjects such as modern warfare, a popular theme with some fans and decidedly unpopular back in Billund. But Siskind also created and marketed kits based on train and castle themes, which very much fell within the LEGO Group’s wheelhouse. Siskind’s first kit for Brickmania was a medieval blacksmith shop; it sold so well that that in 2003, LEGO took notice and licensed the set from Siskind. Consisting of 622 pieces, set 3739 retailed for $39.99. It was the first fan-designed set that LEGO launched. With that, LEGO began to open up to its most creative fans. The monolith had cracked.

Explore the full spectrum of innovation. For more than a decade, innovation strategists such as Northwestern University business school professor Mohanbir Sawhney and consultancies such as Chicago-based Doblin have challenged business leaders to shake off their myopic pursuit of conventional notions of innovation, which too often was confined to product development and traditional R&D, and open their eyes to a far more panoramic view. To reap outsize profits in highly competitive markets, companies must pursue all opportunities to create new revenue streams by introducing clusters of complementary innovations. By itself, a new product is easy to copy. But a full-spectrum approach to innovation, where a family of complementary products with new pricing plans is offered through new channels, is hard to beat.12

The LEGO Group’s embrace of full-spectrum innovation dates back to 1999. As part of an unrestrained effort to stretch out and reimagine the LEGO play experience, the company’s design leaders gave a concept development team an almost heretical assignment: create an entire building system that omits the brick.

After several months of brainstorming ideas, the team came up with a building system where kids could snap together exotic plastic parts to create weird fantasy creatures, such as a caterpillar with webbed feet and an alien’s head. The system allowed for a very LEGO-like, free-form style of play. Kits came without instructions, harking back to the days of classic LEGO. Parts from one kit could seamlessly connect with parts from another kit, just like bricks. Except for one thing: there was no LEGO brick. The kit was made up of wholly original, snap-together pieces that eschewed the LEGO stud-and-tube coupling system. The team called the concept LEGO Beings. The idea was too outlandish to be commercialized, but it did give design leads tangible evidence that they could break out of the LEGO System of Play. What’s more, LEGO Beings became the genesis of one of the LEGO Group’s biggest bets of the new century.

Just when the concept design team was developing LEGO Beings, a new mania for action figures was breaking across Europe and America, led by Hasbro’s Action Man, a modern adventurer who battled archenemies. The LEGO Group’s toy makers moved to capitalize on the craze by creating an action figure of their own, which took inspiration from LEGO Beings. A newly established product development team compiled a one-hundred-page research report on the action figure category and recruited the former head of action figure development for Hasbro to guide the LEGO Group’s foray into the market. After months of experiments, the team conjured a generic, organic building platform—like the one that was created for LEGO Beings—and used it to imagine a cast of kid-magnet characters.

“The driving force behind the action figure category, more than anything, is about triggering boys’ imaginations through role-play,” said Jacob Kragh, who led the new toy’s development effort. “And role-play, more than anything, is about having strong characters.”

Kragh’s team dubbed the new line Galidor, a cool-sounding, nonsensical word, which they hoped would resonate powerfully with nine-year-olds. Galidor featured archetypal, kid-friendly characters from the sci-fi genre—a pair of teenage heroes, sinister but unscary villains, and a sidekick robot—that consisted of a dozen-something parts that kids could connect via pins and holes instead of studs and tubes. To boost the line’s chances of becoming a runaway hit, LEGO followed a marketing script that offered a striking departure from the toy industry status quo. Instead of promoting the toy by tying it to an established TV series, LEGO hired Hollywood producer Thomas Lynch to create its own TV series, Galidor: Defenders of the Outer Dimension, which tied into the toy.

“The idea was to use the TV show to build awareness for [the toy],” said Kragh. “As ratings for the TV show increased, toy sales would follow.”

Galidor marked the LEGO Group’s most ambitious attempt to explore the full spectrum of innovation. From a new-product perspective, Galidor was an entirely new kind of building system that brought LEGO into a new toy category. From a customer-experience perspective, the TV show, as well as a video game and DVD, paved new avenues for interacting with Galidor. From a value-creation perspective, the TV show and video games let LEGO discover untapped revenue streams and recapture the value the line created. And from a delivery perspective, the company’s plan to package Galidor characters in McDonald’s Happy Meals was a clever way to connect with American kids (especially those kids who had previously ignored LEGO) as well as open up yet another source of revenue. (Insert photo 7 shows some of these Galidor products.)

“We wanted to make sure we created new growth streams and more adjacent parts to the core product,” said Kragh. “And then, when we started to incorporate the ambitions we had on the media side with the TV show, our executive team became incredibly enthusiastic about Galidor.”

When it came to taking a 360-degree view of innovation, LEGO didn’t bind itself solely to new product themes. As part of the bid to make LEGO “the world’s strongest brand among families with children,” Plougmann and Kristiansen launched an ambitious drive to expand LEGOLAND theme parks and LEGO-branded stores. The company’s original, flagship LEGOLAND in Billund attracted more than a million and a half visitors every year. Its success led the LEGO Group to launch a second LEGOLAND, outside London, in 1996. Hoping to introduce millions more youngsters to the brand and drive even more demand for the brick, Plougmann accelerated the push into theme parks, launching LEGOLAND California near San Diego in 1999 and LEGOLAND Deutschland outside Munich in 2002 (see insert photo 8).

As for the LEGO store idea, it was not unprecedented. The company had earlier created LEGO Imagination Centers at the Mall of America in Minneapolis and Disney World in Orlando, which connected kids to the brick in an interactive, playful retail atmosphere and promoted the LEGO brand to more than twenty million people a year. With an eye toward creating millions more emotional attachments to the brand, Plougmann promised to launch three hundred additional LEGO stores.

“We couldn’t have a dialogue with an American mother if we always forced her to the shelves at Walmart,” Plougmann explained. “We needed to bring her into LEGO’s world. And that would be through LEGO-branded stores. Along with the LEGOLAND parks, stores would be our brand builders.”

Build an innovation culture. In just a few short years, Plougmann and his team put innovation at the top of their management agenda and drove it throughout the company. Having awakened to the toy industry’s dramatically accelerating pace of change, they recruited the very best design talents and positioned them in some of the world’s most creative hotspots. Having been challenged by the revolutionary transformations in kids’ lives, they pushed designers and developers to think beyond LEGO and imagine play experiences that diminished and even eliminated the brick. They cracked the company’s insular culture by taking the first steps toward opening up the development process to outside contributors. They put a premium on audacity and nonconformity, daring to scuttle a beloved but tiring brand such as DUPLO and replace it with something entirely new. Again and again, they upended the LEGO status quo.

What’s more, the LEGO Group’s executive team built a culture within the company that valued and celebrated creativity above all else. Management encouraged people in every part of the organization to think outside the proverbial box and it rewarded those who did. As a result, LEGO became a freewheeling creative machine, spinning off one big idea after another.

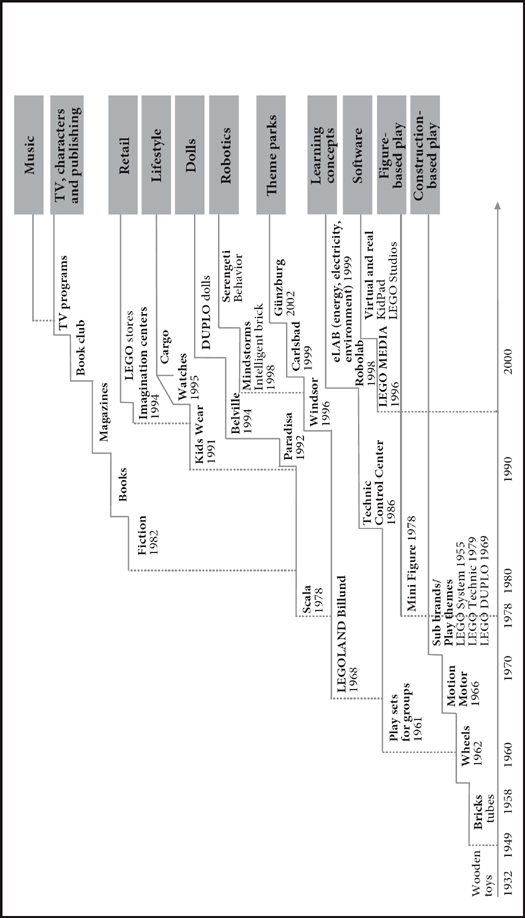

The LEGO product-line structure, 1932-2000.

From the birth of the brick until the early 1990s, LEGO innovated around two core areas: construction-based play with the LEGO System and figure-based play with the minifig. And then, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Plougmann and his deputies pushed LEGO from its core into every conceivable new market—just as he was hired to do. LEGO pursued new channels, new customer segments, new businesses, and entirely new categories of products. It ventured into software with Darwin and LEGO MovieMaker. It launched the new generation of theme parks. It moved into retail with LEGO stores. And it entered the publishing arena with its TV series, DVDs, and video games.

LEGO heeded the proclamations of management strategists and adopted the seven truths of innovation. For a time, the strategy worked. Despite the de-scaling effects of digitization and a horde of new, low-cost competitors that fueled the toy industry’s volatility, the LEGO Group’s sales increased by 17 percent from 2000 to 2002. Looking ahead, senior management remained cautiously optimistic that LEGO would continue to outinnovate its competitors. Kristiansen and Plougmann declared in the company’s 2002 annual report that it had been a “good year.” As for the next year, they predicted that “thanks to its broad product range,” the company could “look forward to a largely unchanged result and turnover in 2003.”

As it turned out, that was wishful thinking. For a company that was struggling to catch up with a world that was passing it by, there was an inherent logic in the LEGO Group’s pursuit of the seven truths. But LEGO had placed a lot of big bets in just a few short years. The company was trying to expand on so many fronts, it was in danger of losing its focus and discipline. If just a couple of those bets went bad, all of the LEGO Group might come crashing down.