Brick by brick: How LEGO Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry - BusinessNews Publishing (2014)

Part I. The Seven Truths of Innovation and the LEGO Group’s Decline

Chapter 1. Stacking Up

The Birth of the Brick

We’ve got the bricks, you’ve got the ideas.

—LEGO catalog, 1992

NESTLED AMONG THE FARMLANDS OF DENMARK’S FLAT Jutland Peninsula, the tidy community of Billund, home of the LEGO Group’s head offices, is in every sense a town that was built on the brick. Billund, residents say, is “three hours from anything”—a long, exhausting drive through windswept farms to either Copenhagen or Hamburg, the nearest major cities. One in four residents of this isolated hamlet owes his or her livelihood to LEGO. And with each passing hour, the LEGO Group’s worldwide reach extends outward from Billund, as another 2.2 million bricks roll off production lines at the company’s sprawling network of factories.1

Billund itself is a toy town, you might say. The LEGOLAND theme park’s castle and towers are the most striking feature of the town’s horizon. The neat rows of yellow-brick houses, topped with red-tile roofs, have the symmetry and stolidity of a little LEGO streetscape. So does the brick-inspired lobby of the LEGO Group’s headquarters, where gigantic LEGO studs and tubes protrude from the floor and ceiling. In every conference room, there’s a clear plastic bowl filled with LEGO bricks. On nearly every desk, there’s an array of extravagant LEGO creations. Watching staffers bustle along the neon-red and yellow hallways, it’s easy to imagine them as LEGO minifigures, with those sunny skin tones and preternaturally happy faces. If there is such a thing as a factory of fun, it is here, in Billund.

And yet life was no fun and games in the Billund of the 1930s, when LEGO was just a start-up. Back then, the village was little more than a smattering of farm cottages scattered along a railway line, a place where farmers scraped out a hard living from the surrounding moors. In a letter written just after World War I, Billund was dismissed as “a God-forsaken railway stopping point where nothing could possibly thrive.”2 It would be difficult to dispute the writer’s claim. The Great Depression had shattered the local economy, which was almost entirely based on agriculture. Photographs from the era show a sparsely populated Billund of humble cottages surrounded by desolate plains.

How, then, did LEGO defy the odds, ascend from a carpenter’s small workshop on the Jutland plains, and arrive in almost every playroom the world over? How has it managed to consistently deliver products, year after year and decade after decade, that fire kids’ imaginations? How was LEGO “built to last” for most of the twentieth century?

LEGO owes much of its enduring performance to a core set of founding principles that have guided the company at every critical juncture over its eighty-plus years.

First Principle: Values Are Priceless

Every venture, at its inception, is imbued with a core purpose and set of values that emanate from the founder, shape the organization’s culture, and largely define its future, for good or ill. Amazon is famous for its “customer obsession” largely because its founder, Jeff Bezos, is hell-bent on making it the “world’s most customer-centric company.” Google’s mission to “organize the world’s information” reflects its founders’ surroundings—Silicon Valley and Stanford University’s School of Engineering—where an outsize pursuit of knowledge is highly valued. And in Bentonville, Arkansas, Walmart founder Sam Walton’s frugality and competitive fire continue to define his company’s core ethos of “always low prices.”

Billund, Denmark, in the 1930s.

Ole Kirk Christiansen, a master carpenter who founded LEGO in Billund in 1932, instilled the company’s quintessential value in its name, a combination of the first two letters from two Danish words: leg godt, or “Play well.”*Reasoning that the more desolate the times, the more parents want to cheer their children, an insight that sustained LEGO through the Great Depression and subsequent global recessions, Ole Kirk used his carpentry skills to create high-quality wooden toys—brightly colored yo-yos, pull animals, trucks. And he framed the company’s overriding philosophy, which holds that “good play” enriches the creative life of a child as well as that child’s later adult life. This philosophy has sustained LEGO for the better part of a century.

Over the decades, LEGO has refined and reinterpreted its mission: to infuse children with the “joy of building, pride of creation”; to “stimulate children’s imagination and creativity”; to “nurture the child in each of us.” But on a fundamental level, the company’s goal has stayed remarkably consistent and is probably best expressed in its current iteration: “to inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow.” This collective desire—to spark kids to pursue ideas through “hands-on, minds-on” play—can be traced to Ole Kirk’s life-altering decision to devote himself and his business to the development of children. Looking back on the earliest days of his start-up, he later wrote, “Not until the day when I said to myself, ‘You must make a choice between carpentry and toys’ did I find the real answer.”3

The LEGO Group’s early years were shaped by hardship. Ole Kirk’s wife died the year he founded LEGO, leaving him with four young sons to raise and a business in the balance. He remarried two years later and guided his young company through the depredations of the Great Depression and Germany’s occupation of Denmark during World War II. Then, in 1942, a short circuit caused an electrical fire that consumed the LEGO factory, as well as the company’s entire inventory and blueprints for new toys. The cumulative effect of so many setbacks nearly overwhelmed Ole Kirk; for a time, he contemplated giving up on his start-up. But out of a sense of obligation to the company’s employees, he summoned the will to start over. By 1944, LEGO had a new factory, one that was designed for assembly-line production. The organization’s tenaciousness—its capacity to push past obstacles in pursuit of success—can arguably be traced to Ole Kirk’s stubborn determination to raise his company out of that fire’s ashes.

Today, every person who’s hired into the LEGO Group’s Billund operations gets a tour of the small brick building, with lions flanking the front steps, where Ole Kirk and his family once lived. There, they learn of another bedrock value that the company’s founder bequeathed to his company: the bar-raising principle that “only the best is good enough.”

The motto grows out of a story that’s entered LEGO lore. Back in the days when LEGO was still producing wooden toys, Ole Kirk’s son Godtfred Kirk—who had worked for the company since he was twelve and would eventually run it—boasted that he had saved money by using just two coats of varnish, instead of the usual three, on a batch of toy ducks (see insert photo 1). The deception offended Ole, who instructed the LEGO Group’s future chief executive to go back to the train station, retrieve the carton of ducks, and spend the night rectifying his error. The experience inspired Godtfred to later immortalize his father’s ideal by carving it onto a wooden plaque. Today, a mural-size photograph of the plaque, which bears the motto “Det bedste er ikke for godt”—“Only the best is good enough”—graces the entrance to the cafeteria in the LEGO Group’s Billund headquarters. It’s a signpost that summons LEGO staffers to exceptional performance.

It’s this melding of these two guiding principles—serving the “builders of tomorrow” and creating “only the best”—that separates LEGO from its competitors and helps it stand out in the global marketplace. Today, anyone who doubts the company’s commitment to quality need only consider the effort and skill that go into fabricating the nearly indestructible LEGO brick, an object so durable and unforgiving that more than half a million people have “liked” the Facebook page “For Those Who Have Experienced the Pain Caused by Stepping on LEGO!”

Second Principle: Relentless Experimentation Begets Breakthrough Innovation

More often than not, game-changing innovation doesn’t come from one all-encompassing, ambitious strategy. It comes from persistent experimentation, which increases the odds that at least one effort will get you to the future first. The business strategist Gary Hamel underlines this notion in The Future of Management, where he asserts, “Innovation is always a numbers game: the more of it you do, the better your chances of reaping a fat payoff.”4 LEGO gets this. It possesses enough creativity to place multiple bets on new innovations and enough tenacity to hang tough long enough to collect its winnings.

Even in its start-up years, LEGO restlessly experimented with new ideas, sometimes making big bets on untested technologies. In 1946, LEGO became the first toy manufacturer in Denmark to acquire a plastic injection molding machine, which cost more than twice the previous year’s profits. (Family members had to dissuade Ole Kirk, at least temporarily, from buying another.) For a rural Danish carpenter who had spent all of his years working with wood, plastics presented a risky, life-altering challenge. The company’s leaders then displayed an uncommon degree of perseverance by spending the better part of the next decade chipping away at a big idea: how to sculpt the LEGO brick.

In a first step, Ole Kirk and Godtfred, who in 1950 was named junior managing director of LEGO, modified British inventor Hilary Fisher Page’s “Self-Locking Building Bricks”—plastic cubes with two rows of four studs, which kids could stack into little houses and other creations—by altering the size of the bricks by 0.1 mm and sharpening the corners. The result was the “Automatic Binding Brick,” made out of cellulose acetate, which featured the little studs that top today’s LEGO brick but was hollow underneath. Although the “binding” bricks were stackable, they weren’t particularly sturdy once stacked. A child could layer the bricks into a wobbly house, but it took just a poke to crash the creation. Thus, retailers returned many Automatic Binding Brick sets unsold to LEGO. It didn’t help that after a visit to the LEGO Group’s Billund factory, the Danish toy-trade magazine Legetøjs-Tidende declared, “Plastics will never take the place of good, solid wooden toys.” Despite consumers’ low regard of plastic toys and some retailers’ outright criticism, the Christiansens persevered.

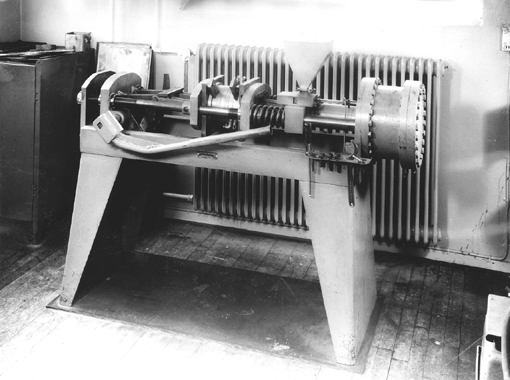

A LEGO molding machine from 1947.

Over the next decade, Godtfred continued to tinker with his “LEGO Mursten” (LEGO bricks). But the bricks still had problems bonding and often suffered from the “spring effect”—when you snapped two bricks together, they’d bind for a short time but then pop apart. Although LEGO continued to manufacture sets of bricks, they sold poorly, at most accounting for 5 to 7 percent of the company’s total sales in the early 1950s.

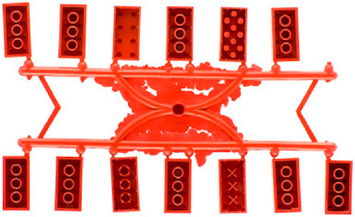

It took years of failed experiments before Godtfred hit on the stud-and-tube coupling system, where the knobs that top one brick fit between the round hollow tubes and side walls underneath another brick. The tight tolerances and flexible properties of the modern brick, which is made from acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), allowed the studs and tubes to remain connected through friction. That design, patented in Copenhagen on January 28, 1958, delivered what LEGO continues to call “clutch power.” When a child snaps two bricks together, they stick with a satisfying click. And they stay stuck until the child uncouples them with a gratifying tug. And therein lies the LEGO brick’s magic. Because bricks resist coming apart, kids could build from the bottom up, making their creations as simple or as complicated as they wanted.

Born out of a seemingly unending series of experiments more than half a century ago, it is clutch power that makes LEGO such an endlessly expandable toy, one that lets kids build whatever they imagine. And it is the brick that became the physical manifestation of an entire philosophy about learning through play.

Early LEGO brick prototypes. Notice that the company experimented with different configurations to find the right “clutch power.”

Although the brick was a breakthrough, it grew out of a long, hard slog. Godtfred’s single-minded pursuit of a far-off goal in the face of adversity is a testament to his persistence, which is too often undervalued in business. Slow, inch-by-inch progress lacks the dramatic gratification that comes with a quick hit. But in the LEGO Group’s case, it produced a winner.

In the years to come, tenacity and experimentation would continue to be prime ingredients in the company’s recipe for innovation, as the company displayed an uncommon willingness to endure setbacks while testing promising ideas. Best-selling product lines such as Bionicle, LEGO Games, and the LEGO Star Wars video game series were each preceded by years of experiments that failed to pan out. Yet never was the LEGO Group’s perseverance and determination rewarded quite so spectacularly as it was with the invention of the “real” (as Godtfred called it) brick, which would prove to be one of the toy industry’s greatest innovations.

Third Principle: Not a Product but a System

The LEGO Group’s breakaway success grew out of its ability to see where the toy world was heading and get there first. The company’s first farsighted move came when it bet on plastic toys and the future of the brick. The second came when LEGO had the insight that it must evolve from producing stand-alone toys to creating an entire system of play, with the brick as the unifying element.

Long before the first computer software programs were patented, LEGO made the brick backward compatible, so that a newly manufactured brick could connect with an original 1958 brick. Thanks to backward compatibility, kids could integrate LEGO model buildings from one kit with LEGO model cars, light pylons, traffic signs, train tracks, and more from other kits. No matter what the toy, every brick clicked with every other brick, which meant every LEGO kit was expandable. Thus, the LEGO universe grew with the launch of each new toy. An early publicity campaign summed up the company’s capacity for endless play (and limitless sales) thusly: “You can go on and on, building and building. You never get tired of LEGO.” Decades before the rise of “value webs” and Apple’s “brand ecosystem” of i-centered offerings, LEGO took a holistic view of its product family, with the ubiquitous brick as the touchstone.

The notion of a LEGO system of play came to Godtfred during a January 1954 trip to the London Toy Fair. Ole Kirk’s health was declining, and Godtfred began to oversee more of the company’s day-to-day management. On the ferry crossing the North Sea, he met up with a toy buyer from Magasin du Nord, the largest department store in Copenhagen. The buyer lamented that instead of delivering the one-off products that so dominated the market, toy makers should focus on developing a cohesive system where sets of toys were interrelated. Such a system would generate repeat sales. The suggestion stuck with Godtfred. After returning home, he spent several weeks working out the attributes that might define a viable system. He eventually identified six features, which he called the company’s “Principles of Play” and issued to every LEGO employee:

1. Limited in size without setting limitations for imagination

2. Affordable

3. Simple, durable, and offer rich variations

4. For girls, for boys, fun for every age

5. A classic among toys, without the need of renewal

6. Easy to distribute.†

Using these principles as a benchmark, Godtfred then reviewed the company’s wide-ranging portfolio of more than two hundred wooden and plastic products. He decided the LEGO brick came the closest to conforming to all six attributes and represented the best opportunity for evolving a true system of play, one that would lend itself to mass production and massive sales.

Along with a small group of skilled designers, Godtfred spent the next year organizing the LEGO Mursten sets around a single, integrated town theme. The revised sets allowed children to create the homes and buildings that had long been featured in LEGO catalogs. The sets also let kids embellish the streetscapes—and thereby discover additional play potential—through a new array of vehicles, trees, bushes, and street signs. The great virtue of the LEGO System was its elasticity. That is, a parent could purchase a kit and then, at the kids’ behest, accessorize it with any number of additional sets. Indeed, LEGO even came out with supplementary “parts packs” for just that purpose. Consisting of just one or two specialized pieces and fewer than fifty bricks, the packs were designed to be inexpensive, impulse add-ons for existing sets.

In a 1955 note to the company’s sales agents, Godtfred highlighted the philosophy that continues to animate the LEGO System: “Our idea has been to create a toy that prepares the child for life, appealing to its imagination and developing the creative urge and joy of creation that are the driving force in every human being.”

Despite Godtfred’s lofty ambition for the set, the LEGO System i Leg (System of Play) was launched at the Nuremberg Toy Fair in February 1955 to decidedly mixed reviews. Commented one buyer: “The product has nothing at all to offer the German toy market.” (Today, Germany ranks as one of the LEGO Group’s leading markets in per capita sales, outpacing even the United States.) But the buyer from Magasin du Nord, who had suggested the systems idea to Godtfred some thirteen months earlier, was so taken with the set that he arranged a lavish ground-floor display for its Danish launch.

The launch took off, as System i Leg’s early success in Denmark and its expansion into Germany nearly doubled sales in 1957 and again in 1958. More important, the set’s promise pushed Godtfred to continue experimenting and eventually develop the modern brick with its stud-and-tube coupling, which quite literally made the System click. With the brick now conforming to Ole Kirk’s exacting, “only the best” standard and the System of Play firmly established, LEGO quickly expanded its town- and street-themed sets, which included a gas station, car showroom, and fire station (see insert photo 2). Indeed, LEGO had hit on a virtuous cycle: as the System evolved and, in the years to come, took in new themes such as castles, space, trains, pirates, and much, much more, kids’ capacity for “unlimited play” grew with it. The LEGO brick’s promise was both infinite and irresistible: the more you buy, the more you can build.

Fourth Principle: Tighter Focus Leads to More Profitable Innovation

When Godtfred bet on the brick, he opted out of producing wooden toys. Dropping the toys that accounted for 90 percent of the company’s product assortment could not have been an easy decision. But Godtfred believed that too many options could overwhelm a nascent effort to create a new kind of play experience—that, in fact, less can be more. Channeling his company’s limited resources in just one area, the plastic brick, could lead to more and more profitable products getting to market. Freed from the distraction of having to create new kinds of wooden toys, designers could pour all of their talents into imagining new play opportunities for the brick.

The notion that a company should focus its resources on a clearly defined core business runs counter to much of the prevailing thinking about innovation, which holds that talented associates should have a broad canvas for creativity and be allowed to search for “blue-ocean” markets or develop “disruptive” technologies (themes we’ll return to later). But Godtfred found that the LEGO System was flexible enough to allow a great deal of innovation within a very tight set of constraints. To him, every LEGO designer’s idea was in scope, so long as that idea was built on the brick and conformed to the System of Play. In the years that followed, as designers improved their ability to extend the brick’s DNA, they went on to create a dizzying array of profit-generating products, from DUPLO bricks for preschoolers and Technic rods and beams for advanced builders to the Mindstorms programmable brick and beyond. But all of those breakthrough products came from innovating “inside the brick.” By strictly defining the boundaries of the company’s core business, Godtfred gave his designers the chance to develop a set of world-beating competencies in brick-based creativity, which LEGO leveraged for years to come. “Less is more” is a principle that many companies forget—and which LEGO itself would forget at the end of the century.

Having bet on the brick, Godtfred continued to channel the company’s efforts into a set of brightly defined boundaries. To protect the System’s integrity, he limited the range of different shapes and colors of bricks that LEGO produced.‡ Seeking to ensure that every LEGO set was compatible with all other LEGO sets, the company’s chief executive personally vetted every proposal for a new LEGO element.§ Rejecting many more ideas than he accepted, Godtfred kept the number of different LEGO shapes and colors in check during the first twenty years of the brick’s existence. His laserlike focus on doing just a few things extraordinarily well—such as designing solely for the brick—foreshadowed a key leadership lesson from another serial innovator, Steve Jobs, who famously quipped, “Innovation is saying no to a thousand things.”5 Knowing what to leave out—even when it’s really good—can sometimes deliver far better results. Take, for example, the LEGO Universal Building Set of 1977. The set consisted of just a few dozen shapes in only seven colors. Even so, its simplicity and utility made it a bestseller.

Godtfred’s stringent control over the range of different LEGO pieces forced designers to create within a limited palette of options. Although it might be counterintuitive, those luminous boundaries helped designers home in on what mattered, which in turn catalyzed their creativity. The 1975 catalog, for example, featured an impressive array of different toys, including an antique Renault car, as well as a helicopter, a Formula One racer, a family of three (with two dogs), a windmill, a Wild West town, a hospital, a train (with tanker, passenger car, and mobile crane), and a train station, all made from the same limited set of shapes and just nine different colors.

Betting on the brick was a risky strategy, as it made LEGO a one-toy company. The LEGO Group’s many competitors only amplified Godtfred’s eggs-in-one-basket gamble. By the mid- to late 1950s, there were dozens of manufacturers of architectural toys, including Minibrix (rubberized, interlocking bricks), Lincoln Logs (notched wooden logs), and Erector sets (small metal beams). For a time, each of those brands was a bestseller. But none amounted to an entire system of play. And so they faded. Only Godtfred grasped the potential of a tightly focused, endlessly expandable, and fully integrated system that was built around the brick.

Fifth Principle: Make It Authentic

At first blush, it’s difficult to see how a universe composed of brightly colored chunks of ABS, the indestructible plastic that’s used to manufacture LEGO bricks, can in any way be construed as authentic. After all, the inert plastic brick, as well as the miniature boats, cranes, doors, electric motors, flags, garages, hinges, hooks, and thousands of other elements that span the alphabet from Aqua Raiders to Znaps (a kind of beam), are the materials by which a child fabricates a fantasy LEGO world. It’s a synthetic world of plasticized ninjas, dragons, the lost city of Atlantis, skeletons, treasure hunters, and a head-spinning array of other unnatural creations. And yet, for LEGO the appeal of what’s real is, well, very real.

LEGO long ago figured out that kids’ fantasy lives grow out of their real lives. That in fact, the everyday world that children observe is the feedstock for their imaginations. Well before the advent of the modern brick, one of Ole Kirk’s top-selling toys was the plastic, lifelike 781 Ferguson Traktor, modeled on the Massey-Fergusons found on many a postwar European farm. The logic was inescapable: if Dad’s got a tractor, the child should have one, too—as well as miniature hoes, cultivators, and other implements that could be attached to the toy. Today, a quick trip through YouTube reveals more than a few clips, posted by grown-up LEGO devotees, of remote-controlled mini Massey-Fergusons custom-built out of bricks.

In the mid- to late 1950s, LEGO continued to make it real by producing a series of mini metal and plastic trucks that lovingly replicated such European auto models as Citroën, Mercedes, and Opel. The first sets to present the modern brick offered town and city features that were familiar to any suburban kid: a fire station, a church, even a VW car showroom and an Esso gas station (see insert photo 2). These and later kits reveled in the promise of one of the company’s 1960s ad campaigns, which proclaimed that whatever you built with LEGO bricks, it’s always “real as real.”

In an increasingly shiny, fabricated world of concocted experiences, we hunger for the authentic. Kids as well as adults gravitate toward experiences that they sense are true and genuine. LEGO gets this. Even when LEGO ventures into a fictional universe that’s “far, far away,” as it does with its Star Wars sets, the effort is rooted in the real. When all of the kit’s 274 pieces are fully assembled, a LEGO X-wing Fighter, to cite just one example from the Star Wars milieu, strikingly mirrors the real deal.

The word authentic is derived from the Greek authentikós, which means “original.” And as we’ve seen, LEGO has cooked up its own recipe for originality. The LEGO brick is the first creation of its kind. The LEGO System of Play is unlike anything in the toy world. If you Google “fake LEGO,” you’ll get more than sixteen million results, a testament to the System’s originality. LEGO is so genuine, it’s spawned a universe of imitators and outright counterfeits. As LEGO demonstrates with product lines offering exotic worlds that are entirely fictional, such as Bionicle and Power Miners, what’s authentic is not always “real.” What are real are the connections that kids and kids-at-heart forge, with one another and with LEGO itself, when they make the bricks click. For many adult fans of LEGO, classic toys such as the Yellow Castle and Space Cruiser, which were unveiled in the late 1970s, summon powerful childhood memories and no doubt draw them to new LEGO offerings for their children. It’s the primal, human-to-human relationships that LEGO fosters—through play, the Internet, fan events, and more—that have helped the brick endure for more than eight decades.

Sixth Principle: First the Stores, Then the Kids

When you walk around the LEGO headquarters in Billund, the company’s respect for children is much in evidence. Flag-size banners of kids at play ring the company’s design and development studio, where extravagant brick creations litter almost every desk. The company’s slogans have included lines such as “Children are our role models” and “We believe in nurturing the child in every one of us.” Such sayings can come off as more than a little cheesy. But the company’s appreciation for children is as important a corporate asset as the brick itself. Because LEGO is a buildable toy that ignites the imagination solely through construction, it depends on kids even more than other toy outfits. Designers and developers understand that even their simplest toy, such as the stripped-down box of basic bricks, requires a child’s hands and mind to bring the kit to life. So it’s surprising to find that while kids are vital to LEGO, much of the company’s attention goes to another constituency.

Although the LEGO Group’s guiding mission is to develop children through play, it’s the stores, not the kids, who rank first among the company’s priorities. It was hardly a coincidence that a retailer—the buyer from Magasin du Nord—inspired Godtfred to concoct one of the company’s foremost innovations, its System of Play. From the outset, Ole Kirk and Godtfred strove to build tight ties with the buyers who stocked LEGO toys. The LEGO Group’s leaders knew that to connect with the kids, they first had to align with the stores.

The imperative that led LEGO to build close, personal ties with retailers was ingrained during the spring and summer of 1951. That year, the company’s sales representatives told Ole Kirk there wouldn’t be any new orders until retailers placed their Christmas purchases after the summer holidays. Out of concern that the company couldn’t afford to manufacture toys that would be stockpiled for months, Ole Kirk decided to shut down the factory for the summer.

Godtfred, however, believed it would be a devastating mistake to suspend operations. Along with his wife, Edith, he drove to every toy buyer in southern Jutland and scored enough orders to keep the factory running through summer. The trip was so successful, he repeated it in other parts of Denmark. Before the year was out, Godtfred had personally visited nearly every buyer in the country.

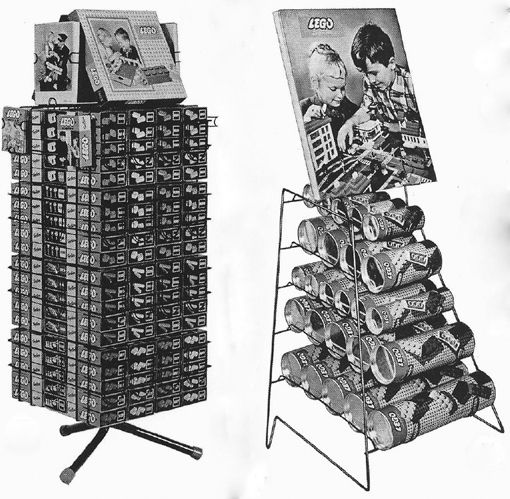

LEGO expanded its network of retailers throughout the 1950s and ’60s, moving into western Europe and the United States and collaborating with buyers to create eye-catching store displays. The company’s 1963 catalog shows an impressive array of in-store materials available to retailers: a calendar, stand-alone racks of toys, hanging signs, lighted window displays, wall posters, display models, and even short movies designed to run in theaters before the main feature. From the outset, LEGO understood that winning repeat sales depended on appealing to the kids, but winning the first sale depended on supporting the retailers.

An aspirational mission. Relentless experimentation. Systems thinking. Discipline and focus. The appeal of the real. Inspiring the customer, prioritizing the retailer. By leveraging these six principles, LEGO embarked on a growth curve that extended its reach—throughout western Europe and on into the United States, Asia, Australia, and South America—and expanded its range of game-changing products, all through the 1960s. Among the highlights:

LEGO store displays from the company’s 1963 retailer catalog.

✵ In 1961, the company’s bricksmiths invented the wheel, a simple round brick encircled with a rubber tire, with a bearing that was innovative enough to justify a patent application. Today, LEGO produces some three hundred million tires per year, more than Goodyear or Bridgestone.

✵ In 1967, LEGO unveiled DUPLO, a line of bigger bricks for preschoolers’ little hands. Derived from the Latin word duplus, “double,” DUPLO proved to be an irresistible gateway brick for LEGO. Because LEGO bricks clicked with the bigger DUPLO bricks, kids could graduate to LEGO when they outgrew DUPLO.

✵ In 1968, the first LEGOLAND theme park, in Billund, opened its gates. Featuring over-the-top attractions—such as the remarkably realistic, thirty-six-foot-tall Chief Sitting Bull, which required more than 1.75 million bricks—Billund’s LEGOLAND still pulls in close to 1.5 million visitors a year.

By the early 1970s, the LEGO Group employed one thousand staffers at its Billund headquarters and was responsible for nearly 1 percent of Denmark’s industrial exports. But then its growth curve plateaued. The product lineup had grown a bit stale, make-or-break Christmas sales were dramatically dropping, and the company’s direction had begun to drift, as Godtfred was not yet ready to cede leadership to his son, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen. “Everything was put on hold for some years,” remembered Kristiansen. “It was a period of uncertainty.”6

No one at LEGO has more brick in the blood than Kristiansen, who grew up with the brick and is a living link to the days when the company’s primary products were wooden toys. (Kjeld Kirk’s surname was misspelled with a “K” on his birth certificate.) He and his sisters were the LEGO Group’s first focus group for testing the brick’s appeal; in 1950, his image appeared on the boxes of some of the LEGO Group’s earliest plastic sets. Noting his sharp instinct for divining what most appeals to kids, former deputy Poul Plougmann called Kristiansen “the Steve Jobs of LEGO.”

In 1979, Kristiansen was just thirty-one when he was appointed president of the company. A quiet, bespectacled man of medium height who frequently pauses to collect his thoughts before he speaks, he shuns the spotlight and shies away from taking any credit for the company’s almost supernatural success from the late 1970s through the early 1990s. But it was Kristiansen who built a management organization around the LEGO System of Play and put the company on a fifteen-year growth spurt, an expansion that saw LEGO double in size every five years. As a first step, he devised what he later called a “development model for the company,” which sought to give the LEGO Group’s designers a vivid sense of direction and consumers a clear choice.

The only known photo of the three generations of LEGO leaders: Ole Kirk, Godtfred Kirk, and Kjeld Kirk.

Before expanding the company’s offerings, Kristiansen laid the foundations for growth. Under his father, the company’s product range had simply been lumped under the brand called LEGO System. Kristiansen set out to build a professional management system by dividing the LEGO Group’s product lines into three groups: DUPLO, with its big bricks for the youngest children; LEGO Construction Toys, which took in the basic building sets that were the heart of the LEGO System; and a third category devoted to “other forms of LEGO quality play material” such as Scala, a new line of buildable jewelry for young girls.

“The thought behind [the reorganization] was twofold,” he told us. “We wanted to make it much easier for consumers to find the relevant product offering for the child. And we wanted to make it much easier for our development and marketing people to work specifically within their own brand profiles, which in turn made it easier for them to see so many more possibilities.”

The result was that a line such as DUPLO became a full-fledged brand in its own right. Relaunched in 1979 with the now famous red rabbit logo, DUPLO grew far beyond bricks to include train sets, DUPLO “people” with movable limbs, doll houses, and licensed characters from the likes of Disney and, later, Winnie the Pooh and Toy Story.

Kristiansen’s second major innovation was to redefine and extend the entire concept of a System of Play. In the mid-1970s, the company had its core LEGO town sets that allowed kids to build full towns with houses, stores, cars, and gas stations. The company also had electric train sets, although the train cars were almost twice the height of the houses in the LEGO towns. In 1974, the company introduced “LEGO family” sets—a granny, mom, dad, and kids with movable arms. At the time, they were one of the company’s bestsellers. But the figures measured in at a maximum height of over ten bricks, so big they wouldn’t fit in the train sets and towered, like Godzilla, over the houses in a LEGO town. In 1978, working with a team of designers, Kristiansen came out with a revised line of miniature figures that were properly scaled to the System. Two years later, he followed up with a revised line of trains that were scaled to these minifigures.

Three sets from the mid-1970s: the LEGO Family, a LEGO train, and a LEGO house. Notice that the family is too large to fit in the train and towers over the house.

Originally launched in 1975, the first of Kristiansen’s little plastic people lacked arms or faces. The oversight was remedied three years later, when the LEGO minifigures, or “minifigs” as they came to be called, were rendered with a pair of black, unblinking eyes, an indelible smile, and an ultra-yellow skin tone. Ten years later, the Pirates line introduced the first minifigs with facial expressions, as well as hooks for hands and pegs for legs. With that, minifigs morphed into nearly anything that LEGO designers could think of: leering vampires, grimacing weightlifters, blissed-out cheerleaders, even famous fictional characters such as Batman, Yoda, SpongeBob, and many, many more. Because it brought role-playing to LEGO and dramatically animated its kits, the minifig might well be the company’s most significant creation, second only to the brick. As of June 2013, more than 4.4 billion minifigs have rolled off the brick maker’s production lines, more than the combined human populations of China, India, Europe, and the United States.

The first LEGO minifigure, from 1978.

Kristiansen’s third significant innovation was to push the notion of themed sets to the fore. Although LEGO already featured the Town line, he championed new themes, which added other dimensions to the play experience. “Instead of talking about children moving through age categories, we began to think about different play ideas,” he recalled. “We were focused more on children’s needs.” With basic bricks, kids built whatever they imagined. With themed sets, kids created whatever the theme inspired. The building experience was less creative, but the play experience was more rewarding. The result was two of the company’s greatest successes, Castle and Space.

Launched in 1978 with a single kit, the Castle line quickly grew into a medieval world of LEGO crusaders, dragon masters, and royal knights that continues to this day. Space took off the same year, and while it featured such endearing curiosities as putting mini LEGO astronauts in open, unprotected cockpits and giving them carlike steering wheels to direct spacecraft, the line became one of the most expansive themes in the company’s history, with more than two hundred individual sets (see insert photo 3). Equally important, Space and Castle cleared the way for other monstrously successful, homegrown themes such as Pirates and even licensed themes such as LEGO Star Wars and LEGO Harry Potter.

The LEGO Castle set #375 from 1977.

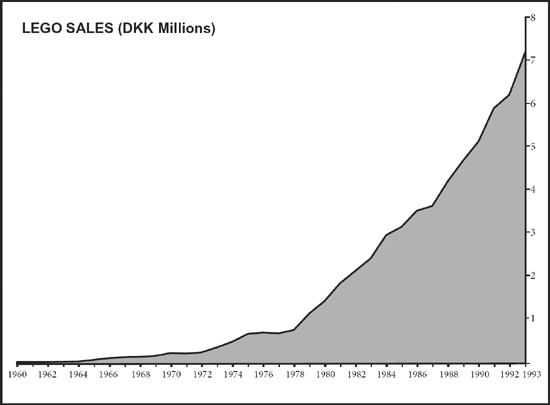

By melding minifigures with themed sets, Kristiansen created a far more immersive play experience. Kids treated their minifigs as analog avatars, imagining themselves as knights or astronauts as they built entire worlds out of bricks. The combination of storytelling (through themes) and role-playing (through the minifigs) electrified a new generation of kids and sparked a period of dramatic expansion for LEGO. Just consider: it took LEGO forty-six years, from its founding in 1932 until 1978, to hit DKK 1 billion in sales (about $180 million at the time). Over the next decade, the sales chart’s slope rocketed upward, increasing fivefold by 1988.

To be sure, LEGO endured some significant failures along the way. Scala, the line of products for young girls, proved a flop and was dropped in 1981. And Fabuland, an ambitious product range aimed at young children and the first LEGO theme to be extended into books, clothing, and a TV series, never caught on and was killed in 1989, after a ten-year run. Even so, the LEGO Group’s growth continued to accelerate. In 1991, LEGO saw an 18 percent jump in sales, at a time when overall toy industry sales rose by just 4 percent. In 1992, LEGO controlled nearly 80 percent of the construction toy market. By the mid-1990s, the small Billund carpentry business had grown into a group of forty-five companies on six continents employing nearly nine thousand people.

The ever-climbing growth in sales made the LEGO Group look great. But as the company entered the 1990s and its sales crested, LEGO began to confuse growth with success. LEGO had expanded its sales effort to target markets around the world—sets were now available to kids from Norway to Brazil—but the company’s rapid globalization was not accompanied by sufficient innovation. Meanwhile, technological advances had begun to radically change the nature of play, as VCRs, video games, cable TV, and computers claimed an increasingly larger share of kids’ lives. In a 2001 interview with Fast Company, Kristiansen conceded that by the mid-1990s, LEGO had become a slow company. “We were a heavy institution,” he declared. “We were losing our dynamism, and our fun.”7

In fact, LEGO, which was on the cusp of being declared the toy of the century, had grown self-satisfied and insular. And that left it flatfooted for its encounter with the rapidly accelerating changes in kids’ lives.

* Christiansen named the company LEGO in 1934.

† There are several versions of the principles, which Godtfred revised over the years. This one is the most concise.

‡ The original colors for the LEGO brick—the bright yellow, red, and blue—were sourced from the Dutch Modernist painter Piet Mondrian.

§ A LEGO “element” is defined as a unique shape and color combination. A red 2×4 brick is an element; so too is a yellow 2×4 brick.