Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney - Howard Sounes (2010)

PART TWO. AFTER THE BEATLES

Chapter 22. THE NEXT BEST THING

LINDA’SPEOPLE

When Press to Play sold fewer than a million copies worldwide, poor by Paul’s standards, he hired a new manager to help revive his career, choosing a straight-talking former Polydor executive named Richard Ogden, who set out a three-year plan to get Paul back in the charts and back on the road, after almost a decade in which McCartney hadn’t toured.

Part of Ogden’s job was managing Linda’s career, too, which meant enabling Mrs McCartney to realise her pet projects, mostly to do with photography or vegetarianism, for which she had become a zealot. Having given up eating meat and fish, and wearing leather, Linda expected everybody else to do the same. She even had the temerity to ask the Duke of Edinburgh how he, as the figurehead for the World Wildlife Fund, could defend shooting birds for sport. The Duke muttered in reply that his eldest son was almost a bloody veggie.

Linda’s vegetarianism was not so much to do with health as a horror of the slaughterhouse. In this regard, Linda found a like-minded friend in Pretenders singer Chrissie Hynde, another American in the British rock industry. Although the two women became close, Linda was capable of telling off even Chrissie if she felt her friend was insufficiently committed to the animal cause, as happened at a gathering of celebrities at Chrissie’s London home. ‘We’re here because we are going to talk about what we can do for animals,’ Hynde told her guests, ‘because we have some influence.’

‘Well, if I were you I’d start by not wearing a leather skirt,’ Linda replied sharply.

It was at this gathering that Linda met the television writer Carla Lane, who became another ally in the cause of animal rights. Carla was a Liverpudlian, slightly older than Paul. She’d been to the Cavern in her youth, but was never a Beatles fan, being more interested in the beetles she could scoop up in her hands and put in her animal hospital. Carla made her name and fortune in the 1970s as the creator of the Liver Birds, a popular television sit-com about two young female Liverpool flat-mates, following this with the equally successful Eighties sit-com Bread, about a working-class Liverpool family. It was Carla’s devotion to animals, though, rather than her Merseyside links, that endeared her to Linda, making two women who were not especially sociable close. ‘We were each lonely people, really,’ observes Carla, noting that although Linda was friendly with Chrissie Hynde and Twiggy, and one or two other women, she was not over-endowed with friends. Similarly, Paul didn’t have many pals. ‘I never saw Paul with mates. He was always surrounded by people, but he was usually in charge of them.’

Though not as rich as the McCartneys, Carla had made very good money in television, investing her wealth in an animal sanctuary at her large country home, Broadhurst Manor, 60 miles from the McCartney estate in West Sussex. Broadhurst Manor was a veritable Noah’s Ark of rescue animals, with Carla always grateful to Paul and Linda for taking on the care of some of her surplus stock. They had the space at Blossom Farm, and already maintained a considerable menagerie of their own. The McCartneys kept approximately nine horses these days, including Linda’s beloved appaloosa stallion Blankit (sired by Lucky Spot, the horse she’d brought back from Texas in 1976); there were numerous cats and dogs, including sheepdog descendants of the late Martha, who’d died in the early 1980s. They also had sheep, a herd of deer, and a pet bullock named Ferdinand that Paul had found loose in the lanes one day, having escaped from its farmer. When Paul discovered the bullock was on its way to slaughter he bought the animal and made a pet of it. The McCartneys also kept numerous small creatures, including rabbits, fish, a turtle that lived in a spacious aquarium adjacent to Linda’s kitchen, and a parrot named Sparky, which resided in an outdoor aviary, saying repeatedly, ‘Ello Sparky. Come ’ere and say somethink,’ mimicking the passing farmhands.

In addition, Carla gave the McCartneys chickens, a blue-grey kitten (upon request from the children) and numerous additional deer, which she frequently found injured in lanes, having been hit by vehicles. Carla would pick the creatures up in her animal ambulance and nurse them back to health, where possible, before releasing them into the wild. On one memorably happy occasion, Carla and Linda both had rescue deer ready to release at the same time, so they arranged to meet on a track that led into the forest on Paul’s Sussex estate (which he expanded considerably in the Eighties, buying two adjacent farms and a 50-acre wood, created a contiguous landholding of nearly 1,000 acres - an area three times the size of London’s Hyde Park).

The deer was in the back of our ambulance and Paul had one at the back of [his vehicle] and we did a one, two, three, let them go. And we watched the two deer that we’d nursed better gallop side by side the length of this lane. There were a lot of people there, staff, and Paul and Linda and I, and what a moment it was! Beautiful … It was just one of the nice things that we used to do that nobody knew about.

Though she meant well, Linda’s concern for animals could lead to muddled thinking. She fed her animals a vegetarian diet whenever possible, even to those creatures that were naturally carnivores. She disapproved of the more pragmatic Carla feeding dead chicks to her rescue foxes, for example, and refused to countenance the idea that when her own domestic cats slipped out of the house at night they might be hunting for rodents. ‘She really was against meat being consumed by [any creature],’ says Carla, who believes Linda would have found a way to feed porridge to a T. Rex if she had one in her care. Linda grudgingly accepted wild animals hunted for survival, but she and Paul were implacably opposed to people hunting for sport, becoming terribly upset if they heard a hunt riding through the area or guns going off. One time, when shooting was taking place within earshot, farmer Bob Languish met Paul storming down the lane. ‘Where are those people shooting those poor little bunnies?’ the musician demanded of his neighbour, who informed Paul mildly that the men were only clay-pigeon shooting.

Animals at Blossom Farm lived until they died of old age, even though some local farmers thought this cruel, pointing out that sheep wear their teeth down with grazing and can starve to death if they become very old. The McCartneys took little notice, choosing to spend whatever it cost on vets to keep their ageing animal friends alive. ‘I remember they were devastated when a cow of theirs died, and they had specialists from all over the place coming to this cow. They were heartbroken,’ says Carla, who admits that most people would think Linda and herself eccentric. ‘We are cranks, let’s face it. We don’t mind being called that.’ And Linda drew Paul and the children into this well-intentioned but slightly cranky way of thinking, the whole family becoming evangelical about animal rights. Slaughterhouses, hunting, vivisection and the wearing of fur were their bêtes noires, with the young McCartneys feeling as strongly as their parents. James McCartney got up in school and gave his fellow pupils a passionate speech about why eating animals was wrong. ‘All [of us] had in common this disbelief in what people do to animals, a complete horror of the abattoir and how anyone can be a part of it,’ explains Carla, who also found time to collaborate on animal rights songs with Linda, a couple of which, ‘Cow’ and ‘The White Coated Man’, Paul helped the women record at Hog Hill Mill. ‘He said, “Come on, our Carla,” and he’d got all the music ready. I used to love it the way he called me “Our Carla”. It was so Liverpudlian.’ Unfortunately, Carla was no more a singer than Linda was.

It was the horror of animals being driven to their deaths for food that gave Linda the impetus to create a cookbook that didn’t use as an ingredient ‘dead animals’, as she pointedly described meat; a book in which she would set down her recipes for the kind of hearty meals Paul liked and that she urged her women readers to serve to ‘your man’ - hardly the sort of language one would expect of a woman who’d been at the heart of the Sixties counter-culture, but there was an old-fashioned side to Linda. Away from the public stage, she played the role of a traditional post-war housewife-mother to Paul and their kids, what Paul had been looking for ever since his own mother died, and Paul and Linda seemed to think this was how other people still lived.

In order to create vegetarian versions of the traditional, meat-based meals Paul had been brought up on, Linda used Textured Vegetable Protein (TVP) products, such as Protoveg, in her versions of such English staples as Sunday roast and shepherd’s pie. Linda created realistic-looking sausage rolls from soya, even a veggie steak Diane. Carla Lane couldn’t understand why her friend felt the need to mimic the look and taste of meat, serving an elaborate soya turkey at Thanksgiving, for instance, and going to the expense of having ‘non-meat bacon’ imported from the United States so that she and Paul could snack on faux bacon sarnies. It didn’t make sense intellectually to reject meat as part of your diet, yet eat pretend meat. ‘I used to say to her, “What, you like bacon so much?” She said, “I’ve got to confess, Carla, I do like the taste, but you know I would never eat the real stuff.”’

To help Linda spread this passionately held but confused veggie message, the McCartneys’ business manager struck a publishing deal with Bloomsbury, whose office was conveniently located next door to MPL on Soho Square, with a vegetarian writer engaged to help Linda turn her veggie menus into a cookbook. For the next two years, Linda worked with Peter Cox on Linda McCartney’s Home Cooking, which put her in the same business as Paul’s former fiancée, Jane Asher. After breaking up with Paul in 1968, Jane had married and had a family with the artist Gerald Scarfe, still pursuing her acting, but also creating a successful second career as a celebrity cake-maker, appearing on television and publishing a series of best-selling recipe books such as Jane Asher’s Party Cakes. Now Linda also thrust herself into the cook-book business. She devised most of her recipes in her kitchen at Blossom Farm which, as she explained in her book, was the heart of the McCartney home and the place she felt happiest. ‘I spend a lot of time in our kitchen. I find it the cosiest, friendliest place in the house,’ she wrote in the introduction to her book. ‘It’s a great place to nurture a happy harmonious family and to spend time with friends, chatting over a cup of tea.’ Yet one of her best friends and most frequent kitchen visitors, Carla Lane, recalls that Paul and Linda were not always a harmonious couple at home in Sussex. ‘They had normal quarrels,’ Carla says. ‘[But] they were never violent. It was, “Oh, alright!” The slam of the door.’

Although Paul enjoyed the country, friends gained the impression he sometimes felt bored at Blossom Farm, hankering for the road and his old life in London, where he had been part of a community of musicians. Although Paul kept the house in Cavendish Avenue, he wasn’t there much, and didn’t tend to use London studios as he once had. Now that Paul owned his own recording facility at Hog Hill he had no need to be at Abbey Road Studios or AIR, where in the past he’d hang out with old friends and meet up-and-coming musicians, getting energy and ideas from what other artists were doing. Everybody who came to work at Hog Hill Mill came at Paul’s invitation, resulting in a slightly stale environment.

In the summer of 1987 Paul started playing with new musicians at Hog Hill, recording demos and auditioning for a band he would ultimately take out on the road. Paul ran down favourite rock ’n’ roll songs with these musicians, numbers including ‘Kansas City’, ‘Lucille’ and ‘That’s All Right (Mama)’, which he sang with the pleasure of a middle-aged man reconnecting with his youth. His engineer recorded the sessions, and when Paul played the tapes back he decided he wanted to put them out as an album.

Richard Ogden was concerned that the time was not right for such a record. Paul’s next major release had to be a strong studio album, one that would make up for Press to Play. Ogden also feared an album of rock ’n’ roll covers might be reviewed critically in comparison to John Lennon’s 1975 Rock ’n’ Roll album. When Paul insisted, Ogden had the novel idea of allowing a Russian company to release a Paul McCartney ‘bootleg’. Despite being banned in the USSR during the Cold War, the Beatles’ music had been and remained hugely popular behind the Iron Curtain, with Soviet fans trading bootleg recordings of their songs. With the rise of the reformist Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, it was becoming easier to get genuine Western records in the USSR, and it seemed a fun idea to allow a Russian label to sell an apparently pirated McCartney record in traditional Soviet style. EMI licensed the Russian label Melodya to manufacture 400,000 copies of Paul’s rock ’n’ roll LP, guessing they would print more and that fans who wanted it in the West could buy Soviet imports, which is what happened when CHOBA B CCCP (Russian for ‘Again in the USSR’), was released the following year.

Around the same time, the star agreed that EMI should issue a new ‘best-of’ LP. Although covering some of the same ground as Wings Greatest, released in 1978, Paul McCartney: All the Best sold strongly in the build-up to Christmas 1987, with Paul appearing on British chat shows to promote it. It was on occasions like this that the Wings Fun Club and Club Sandwich magazine came into their own, Paul’s fan club secretary mobilising members to pack TV show audiences just as Brian Epstein used to do. As a result, Paul got a rousing reception when he walked out on stage at the Wogan show, the Roxy, and Jonathan Ross’s Last Resort, three programmes he graced that winter. With typical professionalism, McCartney invited the Last Resort house band down to Sussex to rehearse with him in advance of the Ross show, giving the boys a guided tour of his Beatles museum. Band leader Steve Nieve introduced Paul briefly to his wife Muriel. The couple were impressed a few years later when they ran into Paul again and he immediately greeted Muriel by name, demonstrating a phenomenal memory. ‘I’ve seen him do this many times,’ says Nieve. ‘He has this ability to put people so at ease around him - remarkable how he keeps names and faces.’

Going round the TV studios helped All the Best turn double platinum, a success tempered by the death in December of Paul’s beloved Aunt Ginny. She died of heart failure at 77. Ginny had been among the last of Jim McCartney’s siblings. Only brother Joe and his wife Joan were left now from that generation, enjoying a comfortable old age thanks to the McCartney Pension. ‘Paul was looking after everybody, he always has done. But always very quiet, you see. That’s why I get bloody mad when I hear people say, “Er, he’s got all that money, you’d think he’d do so and so,”’ says family member Mike Robbins. ‘He’s been giving money to charity quietly, and looking after people quietly, for many, many years.’ Several relatives had received substantial cash amounts, with Paul helping relations buy homes, but the more he gave the more some of them wanted. ‘They did used to moan at Christmas,’ reveals Paul’s record plugger and MPL gofer Joe Reddington. ‘[They’d] phone Alan Crowder up, “What’s the present this year? Oh Christ, haven’t you got anything better?” … Just unbelievable, these people.’

While he might write five-figure cheques for relations, and he had given Linda some high-price jewellery over the years, Paul usually bought inexpensive gifts for the family at Christmas, typically popping into Hamley’s on Regent Street - a short walk from his office - to get the kids the colouring pencils they liked. Recalls Joe Reddington:

I remember one year we are standing in the queue [at Hamley’s] and I’m standing behind Paul, and this guy behind me, he was an American, he said, ‘Excuse me, who’s that in front of you? That’s not Paul McCartney, is it?’ ‘I don’t know actually,’ and then Paul turned round and said, ‘Yes it is,’ and he signed all this stuff this guy was getting for his kids to take back to America.

NEW BEGINNINGS

After the twin flops of Give My Regards to Broad Street and Press to Play Paul needed what was in effect a comeback record to remain an active headline star into the 1990s. He wasn’t prepared to step off the merry-go-round as John Lennon had done. To help Paul achieve his ambitions, MPL got the star together with Elvis Costello, a talented singer-songwriter with whom Paul could write, sing and record, also a young man - Elvis turned 33 in 1988 - of strong character whom everybody hoped would be able to stand up to Paul in the studio, pushing him to do better than his usual ‘I love you Linda’ material.

Costello found McCartney a disciplined, regimented writer. Elvis tended to write his lyrics first, then make the music fit.

If the words demanded it, I wouldn’t develop the melodic line, I’d just add a couple of bars. He [Paul] thought that sounded messy. He likes logic in the lyrics, too. I might throw in ambiguous things, because I like the effect that has on the imagination. But he doesn’t like anyone to walk into the song with green shoes on, unless they were wearing them in the first verse.

To record these new songs, the basis of the album Flowers in the Dirt, Paul assembled a band around the Scots guitarist Hamish Stuart, 38-year-old founder of the Average White Band, whose life was changed by hearing the Beatles’ ‘From Me to You’ as a boy. ‘It was the moment for me when things went from black and white to colour. It’s amazing the number of people who describe it that way.’

Although the original idea was that Elvis Costello would co-write and co-produce Flowers in the Dirt, the old problems soon re-emerged. Paul wanted to do things his way, and Elvis was pulling in a different direction. ‘It was pretty obvious pretty quickly that it wasn’t going to work as a co-production, so things changed and it moved on and some stuff got discarded,’ comments Hamish Stuart. ‘They were kind of banging heads a little bit. Elvis had one way of working, and Paul was more about embracing technology at that time and it just didn’t work, so Elvis kind of left the building.’ The Costello sessions yielded several album tracks, though, including the poppy ‘My Brave Face’ and ‘You Want Her Too’, sung as a duet in the way Paul harmonised with John on ‘Getting Better’, McCartney’s sweet voice undercut by Costello’s caustic interjections.

The drummer in Paul’s new band was Chris Whitten, who’d also worked on the CHOBA B CCCP sessions. Enlarging the group, Paul hired guitarist Robbie McIntosh from the Pretenders. These three musicians helped Paul complete Flowers in the Dirt and formed the basis of his new road band, adding 32-year-old keyboard player Paul ‘Wix’ Wickens, whom Paul and Linda were encouraged to learn was ‘almost a veggie’. Increasingly, the McCartneys had little time for anybody who wasn’t vegetarian. Paul was paying good wages, the new band members getting £1,000 a week as a retainer ($1,530), £3,000 a week ($4,590) for when they were rehearsing and recording, rising to £5,000 a week ($7,650) on the road, generous by industry standards. Paul had learned the lesson of Wings. He made it clear that he’d been hurt by the stories Denny Laine sold to the Sun after the old band broke up, and wouldn’t appreciate it if anybody in the new group did anything like that.

Meanwhile, Paul’s other, more famous former band was about to be inducted into the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame, an institution co-founded in 1983 by Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner that had already gained prestige in the music community. Stars were falling over themselves to be inducted into the Hall of Fame at the annual ceremony in New York, and it was expected that Paul would join George, Ringo and Yoko at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on 20 January 1988, when the Beatles’ fellow inductees would include the Beach Boys and Bob Dylan, who counted among Paul’s musical heroes. But Paul didn’t show. He boycotted the event because George, Ritchie and Yoko were suing him over a deal the Eastmans had struck when he signed back with Capitol Records after a brief spell with CBS, winning him an extra per cent royalty on the Beatles’ back catalogue. When the other three found out Paul was getting more than them they demanded parity, the dispute settled when Capitol gave all four partners an extra per cent on CDs, which were replacing vinyl. As of January 1988, however, the Beatles partners were in deadlock over the issue.

Paul had his publicist release a statement explaining his absence from the Hall of Fame function: ‘After 20 years, the Beatles still have some business differences which I had hoped would have been settled by now. Unfortunately, they haven’t been, so I would feel like a complete hypocrite waving and smiling with them at a fake reunion.’ After Mick Jagger introduced the Beatles at the Waldorf-Astoria, it fell to George Harrison to say how honoured the band felt to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, joking, ‘I don’t have too much to say because I’m the quiet Beatle.’ Then it was Yoko’s turn to speak.

Despite not attending the dinner, Paul and Linda had a keen interest in events in New York and early the next day Linda called her friend Danny Fields at his Manhattan apartment to ask what had happened. Danny, who’d helped discover Iggy Pop and managed the Ramones during his career, aside from his work as a journalist, had a seat on the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame nominating committee. ‘Did you go last night?’ Linda asked her friend, calling from her country kitchen at Blossom Farm.

‘Yeah. You would have had such a good time,’ Danny drawled in his camp manner, ‘you would have heard Yoko’s speech.’

Knowing the McCartneys would want to hear what Yoko said, Danny had recorded her speech, and he had his tape machine cued up in anticipation of Linda’s call. He asked coolly whether she and Paul would care to listen to what Yoko said, and heard Linda telling Paul to pick up the extension. ‘He picks up the phone and I press the tape.’ All three listened as Yoko told the Waldorf that if her husband had been alive, he would have attended the induction, which was as neat a put-down of the McCartneys as she’d ever made. Danny listened for a reaction. ‘Paul said, “Fucking cunt, makes me want to puke.”’

Paul continued working on Flowers in the Dirt at Hog Hill Mill throughout that summer, taking a break in August to visit Liverpool, where he was shocked to discover his old school had fallen into dereliction. Despite its long and illustrious history, the Liverpool Institute had been closed in 1985 by Liverpool City Council, when the council was under the sway of the militant socialist Derek Hatton, who was himself an old boy. The closure was not so much to do with Hatton’s socialist principles as with Liverpool’s declining population. Apparently there weren’t enough clever boys in the shrinking city to fill such an elite school. Four years on from its closure, Paul was dismayed to see that the Inny had become a ruin. The roof was letting in so much rain the classrooms were flooded and rats scurried along corridors that had once resounded to cries of ‘Walk, don’t run!’ Paul had a film made of himself on a nostalgic tour of this sad old place, later released as the documentary Echoes, during which he remembered himself and cheeky school mates and eccentric masters in happier times. Privately, he ruminated on how he might rescue the school.

Since the Toxteth riots, Paul had been looking for a way to give something back to Liverpool. Following his visit to the Inny he decided the school should be the focus for his philanthropy. But what was one to do with the place? Initially, McCartney thought he might simply put a new roof on the Institute, to save it from total ruin, but as he looked into the problem more deeply he saw that the only way to save the building in the longer term was to give it a use and, because of its history, that had to be an educational one.

George Martin, one of the few people in whom Paul placed unswerving trust, mentioned that he’d been helping an entrepreneur named Mark Featherstone-Witty raise money for a school for performing arts in London, based on the New York School of the Performing Arts depicted in the movie Fame. A Fame school for Liverpool might be a use for the Inny. Paul was circumspect. Traditionally, show business is an industry where people learn by experience. He hadn’t gone to a school for performing arts. The idea was anathema, rock ’n’ roll being about self-expression and rebellion. George Martin, a graduate of the Guildhall School of Music, took a different view. He believed there was a place for a formal musical education, and a need to teach young people the essentials of the music business - if future Lennons and McCartneys weren’t to be ripped off, as Paul felt he’d been with Northern Songs. Sensible George went some way to persuade Paul that a Fame-type school for Liverpool was therefore a worthwhile project. McCartney’s primary motivation remained saving the Inny, though, and, canny as ever with money, he didn’t propose to buy the place. The hope was that Liverpool City Council, and the charitable trust in which the building was held, would give the premises to Paul if he devised a regeneration plan.

In April 1989, Paul wrote an open letter to the Liverpool Echo asking his fellow Merseysiders if they wanted a Fame school: ‘I got a great start in life courtesy of Liverpool Institute and would love to see other local people being given the same chance.’ Readers phoned in 1,745 votes in favour, 48 against. The following month, Paul invited George Martin’s friend to MPL to talk about beginning the process.

Mark Featherstone-Witty proved to be an ebullient, jokey fellow of 42, with a theatrical and slightly posh manner (Paul worried that his double-barrelled name would raise hackles on Merseyside) and a varied CV ranging from acting to journalism to teaching, the last of which led him to create a number of private educational institutions. ‘Then the key moment occurred, the key moment, whereas I was sitting in the Empire Leicester Square and saw Alan Parker’s film Fame, and I thought, “That’s what I’m going to do next.”’ In emulation of what he had seen at the pictures that day in 1980, Featherstone-Witty worked to create the British Record Industry Trust (BRIT) School in Croydon, which was established with the help of George Martin and others. Now he wanted a new project.

Although Mark had met many famous people working on the BRIT School, when Paul walked through the door at MPL the entrepreneur was overwhelmed.

You are trying to carry on a reasonable conversation, but one half of your mind is saying, I don’t bloody believe it. I just don’t believe it. I’m actually talking to Paul McCartney! Over years of course that’s completely gone, but at the time I was just amazed … I’ve seen the same reaction with other people.

Despite Mark’s being star-struck, the meeting went well. It was agreed that the entrepreneur would approach Liverpool City Council with Paul’s backing to see if it was feasible to turn the Inny into what Paul wanted to call the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts (LIPA). To show he was serious, Paul pledged £1 million ($1.53m) of his own money, but, shrewd as ever, he didn’t hand it over all at once. He advanced Featherstone-Witty small sums initially. ‘It was £30,000 [$45,900]. Let’s see what you can do with it. So it was to some extent payment by achievement really. Also the payment needed to be matched with a payment, not simply from him, but from other people. He was never going to be the sole funder.’ Still, having started the process, Paul committed himself to a project that would take up a lot of his time, and require much more of his money, over the next few years, while Mark discovered that the charming superstar he met on day one could also be ‘a right bastard’.

BACK ON THE ROAD

The first single from Flowers in the Dirt was released in May 1989, the catchy but unfulfilling ‘My Brave Face’. Though it wasn’t a hit, the LP was greeted as a return to form featuring several strong songs such as ‘Rough Ride’ and ‘We Got Married’, which seemed to document Paul’s early relationship with Linda, vis-à-vis John and Yoko, ‘the other team’. The LP went to number one in the UK, with Paul appearing on TV shows to promote it prior to his first tour since 1979.

Ticket prices were to be modest. Paul was less interested in enlarging his fortune than in playing to as many people as possible, partly because he and Lin wanted to use the concerts to proselytise vegetarianism and ecology. The tour schedule was arranged to coincide with the publication of Linda’s new vegetarian cookbook, with the 81-strong tour party served a meat-free diet backstage. Remarkably, audiences front of house wouldn’t be able to buy meaty snacks, not even hot dogs at Madison Square Garden. MPL banned such concessions, licensing instead the sale of veggie burgers. To accompany the tour, MPL commissioned a 100-page programme that included information about acid rain and deforestation, and exhortations to turn veggie. Unusually, the programme was given away free.

Alongside didactic articles about vegetarianism in the tour programme, Paul took the opportunity to tell his audiences his life story. A series of long interview features saw him correcting what he viewed as misinterpretations about the Beatles’ history. He made the point strongly that he, rather than John, was the Beatle most into the avant-garde in the Sixties. Paul was checking out the new music and meeting new writers along with his friend Barry Miles, ‘when [John] was living out in the suburbs by the golf club with Cynthia’. This was a foretaste of an authorised, putting-the-record straight biography Paul had started work on with Miles, who’d become a biographer of distinction in recent years, writing lives of his friend Allen Ginsberg and other counter-culture figures. Miles had come up with the idea of the book, Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now, agreeing to let Paul vet the manuscript and, perhaps surprisingly, retain 75 per cent of the royalties, meaning it was really going to be Paul’s book.

Other old friends found themselves back in Paul’s orbit as the world tour kicked off. Richard Lester had been hired to make a montage film introduction to the concerts, and to direct a full-length concert feature, the pedestrian Get Back. Linda’s artist friend Brian Clarke was commissioned to create the stage set, as he had the Flowers in the Dirt album cover. To publicise the tour, Paul hired a significant new associate, a likeable former tabloid newspaper journalist named Geoff Baker, whose qualifications for the job included boundless enthusiasm for Paul’s music, as well as sharing Paul and Linda’s fondness for dope and their zeal for vegetarianism.

Richard Ogden asked Paul what songs he was going to play on stage, urging him to perform his greatest hits, which meant Beatles songs as well as the likes of ‘Live and Let Die’. Up until now, Paul had never performed more than a handful of Beatles’ numbers in concert, but feeling the need to come back strongly after ten years away from the stage he drew up a set list that featured 14 Beatles tunes, approximately half the show. He had to learn to play many live for the first time, the Beatles never having performed them on stage, though paradoxically his sidemen had in other bands, Beatles songs having become common to all musicians. As Hamish Stuart observes, ‘some of them we knew better than Paul did’.

After warm-up shows in London and New York, the tour opened in Oslo on 26 September 1989, the first of a run of European arena concerts, after which Paul took his band to North America, returning to England in January 1990 to play Birmingham and London. To interject a brief personal note, the first Paul McCartney show I ever saw was on this tour, at London’s Wembley Arena in January 1990. McCartney’s solo career had made little impression on me so far. What I’d heard on the radio of his work with Wings and afterwards seemed lightweight, and I didn’t own any of his records. The Beatles were another matter. Although they were stars before I was born, the energy and creative brilliance of the band had captured my imagination, as with millions of others. The Beatles cross generations. I therefore attended my first McCartney show with mixed feelings, as I’m sure many others did during that tour. One was coming primarily because of the Beatles, rather than the music Paul had made since 1970, and hoping not to hear too much of the latter.

McCartney bounded on stage, chubby and grey at 47, but evidently eager to entertain us. His band seemed up for the challenge, too, though Linda appeared less engaged than Hamish, Robbie, Chris and Wix, sitting awkwardly at her keyboard, a Union flag draped next to her, periodically making V-signs as if impersonating Winston Churchill. When the show opened with ‘Figure of Eight’, one’s spirits sank. Were we to be subjected to a series of mediocre new songs? Thankfully, the friendly opening bars of ‘Got to Get You into My Life’ followed, the start of a sparkling stream of Beatles songs. To see and hear Paul McCartney perform these iconic songs was genuinely thrilling, and unlike his contemporary Bob Dylan who deliberately changes his songs live to keep the work fresh for himself and his audience, McCartney and his band were playing these classics like they sounded on the records, which is the way you want to hear them, at least the first time. ‘You owe something to the music to present it in as authentic a way as possible,’ comments Hamish Stuart. ‘I remember “Can’t Buy Me Love”. Robbie basically played the solo note for note, because that’s part of what was written.’ Although London audiences have a reputation in the rock industry for being reserved and undemonstrative, compared to elsewhere in the UK, and abroad, people were weeping with emotion, couples were embracing. ‘Sometimes it was hard to watch,’ says Hamish. ‘Look away or you get drawn in and forget what you’re doing.’

To perform ‘Fool on the Hill’ Paul brought an artefact of swinging London on stage, the multi-coloured piano that Binder, Edwards and Vaughan had painted for him in 1966. Paul played this fabulous Joanna on a platform that elevated and rotated as he sang, causing him to rename the instrument his Magic Piano. The crowning moment of the show came, however, in the encore when McCartney picked out the plangent opening chords of ‘Golden Slumbers’ on a Roland keyboard, going on to perform the complete Abbey Road medley, culminating in the sublime ‘The End’, the Beatles’ final exaltation to love one another proving enduringly powerful.

This spine-tingling moment was the closest one could get in 1990 to experiencing the magic of the Beatles live, and it was perhaps better than seeing the boys in the Sixties, in that Paul was performing a complex album piece the Beatles never staged, with state-of-the-art sound equipment and amplification, so it sounded great. I walked away from the show a convert to Paul McCartney as a live performer, and urged everybody I met who hadn’t seen McCartney in concert to do so.

Off stage, Paul and Linda were coping with a difficult family situation. As noted, Heather McCartney had long found the McCartney name a burden. If she was introduced simply as Heather, people showed little interest in her. ‘Then somebody would say McCartney and really emphasise it and I’d just watch their face change.’ For a fairly simple person who didn’t have a strong idea of herself, or what she meant to do in life, this turned into an identity crisis, and in 1988 the 25-year-old admitted herself to a private clinic in Sussex.

After her treatment, Heather went to the United States to spend time with her natural father, Mel See, whom she called Papa, and his girlfriend Beverly Wilk, who lived with Mel in an adobe on the opposite side of Tucson to the McCartney ranch. Mel continued to pursue his interest in anthropology, and he and Beverly took Heather with them to Mexico to visit native Hoichol Indians, who made a big impression on the young woman. Heather admired the Indians’ uncompromising way of life, living on the periphery of the modern world, and picked up design ideas for her new hobby of pottery. Back home in Rye, pottery was a long-established industry, with five potteries in the town at one time. Heather had gone to school with the son of one of the most eminent Rye potters, David Sharp, and worked for a time with another local potter.

During her visit to Arizona, Heather seemed a fragile, mixed-up girl to Mel and Beverly, who says: ‘I think she just needed to get away and find herself.’ Despite the effort Paul and Linda had put into parenting, and the public image they projected of a happy and successful family, it seemed Heather had been left emotionally scarred by her upbringing, first in an unhappy marriage, then with a stepfather who happened to be one of the most famous people in the world. ‘I guess if you had a dad who let someone else adopt you [that would be an issue], and then being in a family where you’re the odd girl out,’ comments Beverly. As a self-made man, Paul was ambitious for his children to build careers of their own, but Heather was a dreamy type, not academically bright, a girl who was content to potter about at home with her roll-ups and pets. She also seemed scared of being identified as a McCartney by members of the public, travelling in America under a nom de plume. One day, when Beverly took Heather to the bank in Tucson, the young woman emerged in an unsettled state saying that she’d signed for her money in the wrong name. ‘I don’t think she sometimes knew who she was - I thought, Wow, what a way of living! ’

Although she enjoyed visiting Arizona, Heather soon returned to the family estate in Sussex, which she considered her real home, and here her emotional problems returned. During the early part of Paul’s world tour, the press reported that Heather had again been admitted to a clinic. ‘I think she has identity problems. It’s a lot of pressure on a child to have to live in the limelight all the time,’ Mel told a journalist; ‘she finds it difficult to be a member of such a famous family.’ Fortunately, Paul and Linda had arranged the European stage of their tour in such a way that they flew home most nights, meaning they could see Heather almost daily. As Heather got better, her parents felt confident enough to continue the tour further afield.

Paul took his band back to North America in February 1990, after which they played Japan, almost exactly ten years after Paul had been deported from the country. Then it was back to the USA, where MPL had cut an advantageous sponsorship deal with Visa. This involved the credit card company paying MPL $8.5 million (£5.5m), which covered most of the tour expenses, further agreeing to run nationwide television ads featuring Paul. The ads used snatches of his Wings and solo career songs, urging Visa card members to use their card to buy tickets for his concerts. (MPL had tried to get permission from Apple to use Beatles songs in the ads, but Apple refused, meaning George, Ritchie and Yoko wanted to limit the extent to which Paul could benefit from Beatles material.) The TV ads caused Paul’s ticket sales to rocket. From selling 20,000 tickets for an average city, there was demand for 100,000 tickets per stop, transforming an arena tour into a stadium tour, which Paul capped on 21 April 1990 by playing a record-breaking show before 184,000 people in Rio de Janeiro.

After South America, Paul returned to the UK to perform in Scotland and Liverpool, the latter show staged in the disused King’s Dock as a fundraiser for LIPA. Backstage, Paul was reunited with several old boys from the Inny, including Ian James who’d helped teach him how to play guitar when they were teenagers. When Paul became a star, Ian didn’t get in touch ‘because I didn’t feel it was right somehow, like taking advantage’. He hadn’t seen his mate for 30-odd years when Paul and Linda walked into the marquee. ‘It was like the King and Queen’s arrived,’ he recalls. Emphasising this quasi-regal feel, which became increasingly pronounced over the next few years, guests were invited up one at a time to be received by McCartney. Ian hung back, falling into conversation with Paul’s brother Mike. Then Paul saw Ian and all formality was forgotten: ‘as soon as he saw me he came over. We just hugged.’ Three decades had passed, the schoolboys had become middle-aged men, but their friendship was somehow unchanged. ‘So from that point onwards we’ve stayed in touch, and I’ve been to a few things like his office Christmas party … Linda would always invite the wife and me. She was a lovely woman.’ It is worth emphasising again the paradox that almost everybody who knew Linda liked her, talking of a warm, unpretentious, friendly person, yet her public image was of a pushy opportunist who’d cheated Jane Asher out of her destiny. Part of the problem was that Linda didn’t come across well with the press, journalists finding her gauche and abrasive. She appeared that way on stage, too.

Two weeks after Ian James met the McCartneys backstage at the King’s Dock, Paul played a charity show at Knebworth, a country estate in Hertfordshire. The concert yielded a notorious tape of Linda singing backing vocals. As we have seen, it was never Linda’s desire to perform live with Paul; she did so to please him. As she became older, she felt less inclined to leave her home - where she was happy with the children and her animals - to perform, and she had to be cajoled into going on the road in 1989-91. She was particularly reluctant this time because Paul would be performing Beatles songs, which Linda had no part in creating, as opposed to her role in Wings. Comments Hamish Stuart:

I think she felt more at home back in the Wings incarnation because she was really a part of that thing. With this band it was a little broader in scope, because of the fact we were doing Beatles tunes and things like that and I think maybe she didn’t feel quite as comfortable. But everybody tried to make her feel comfortable, and Wix was very good at finding good [keyboard] parts for her that fit with what everybody else was doing … Sometimes she had it tough on the road when she wanted to be home.

Inevitably, Linda was criticised for touring with Paul, and it seems she was not held in universally high regard backstage. When they played the Knebworth Festival on 30 June 1990, a technician isolated Linda’s vocal and made a bootleg recording, Linda McCartney Live at Knebworth, that elicited hoots of laughter from almost everybody who heard it. Singing backing vocals to ‘Hey Jude’, Linda was heard droning the na na na na-na-na nas in the manner of somebody getting up in a pub on karaoke night. Band members defend Linda, saying anybody can sound rotten if you isolate them on stage, especially at an open-air gig like Knebworth, but the evidence is clear. Linda was a flat note in the band, slogging her way joylessly through these shows to keep Paul happy, and there was much more of this to come before she could go home to Sparky, Blankit and her other pets.

The success of the Visa ad campaign led to Paul returning to the US to play an additional series of stadium shows during the summer of 1990. The band rehearsed ‘Birthday’ from the White Album so that Paul could treat his Washington DC audience to the song on 4 July. The tour finally concluded in Chicago at the end of that month, by which time Paul had played to 2.8 million people in 13 countries - the longest and most successful tour of his career to date. By getting back to a Beatles-heavy set list he had recaptured the attention of a vast international audience, who remained bewitched by the fab four. It was a lesson he didn’t forget, repeating the formula for every subsequent tour he undertook, gradually increasing the Beatles content until he became a veritable Beatles jukebox, which was great for audiences. The situation was now clear. With John Lennon dead, and Paul, George and Ringo locked in almost constant disagreements over money, the next best thing to experiencing the magic of the Beatles was to see Paul McCartney live. It has been true ever since.

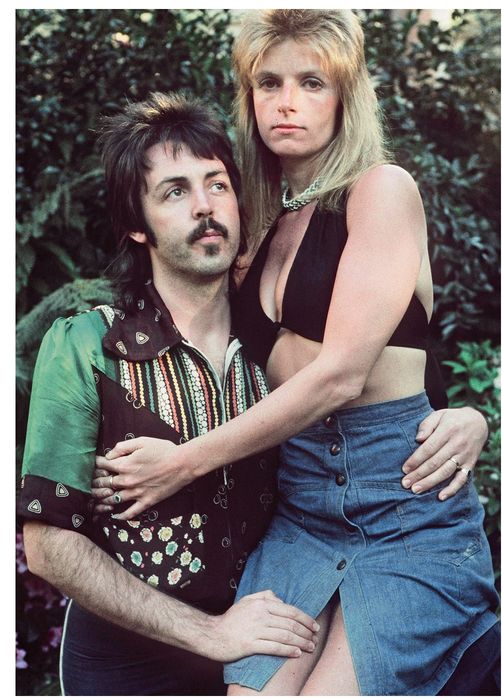

Some of the music Wings made in the 1970s wasn’t as good as Paul’s earlier work. Some of the outfits and hair styles Paul and Linda wore were very much of that era.

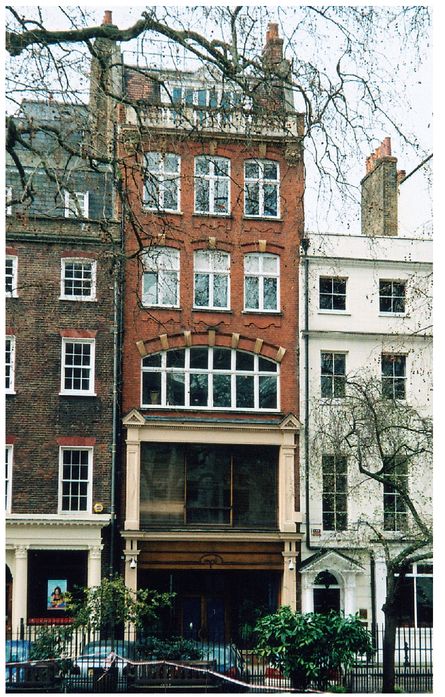

In the late 1970s, Paul moved his company, McCartney Productions Ltd (MPL), to this handsome townhouse in London’s Soho Square.

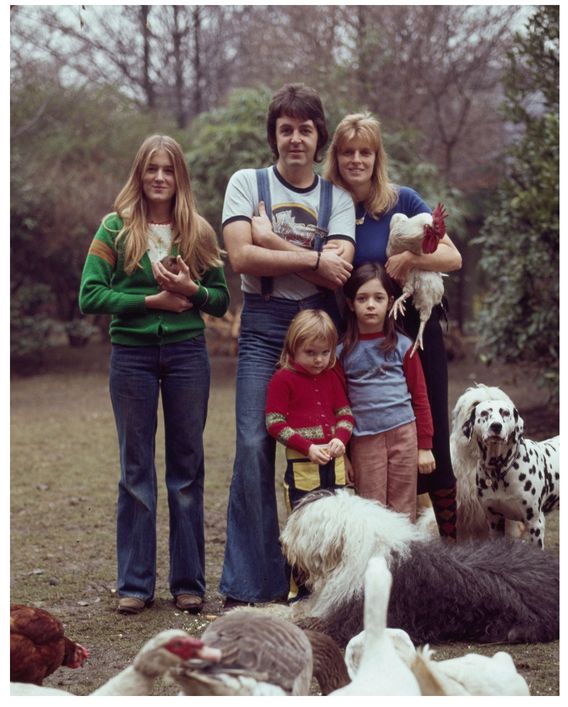

This charming family picture shows the McCartneys with some of their pets in the garden of their London home, April 1976, just before the Wings Over America tour. From left to right are 13-year-old Heather, Paul, 4-year-old Stella, Linda and 6-year-old Mary.

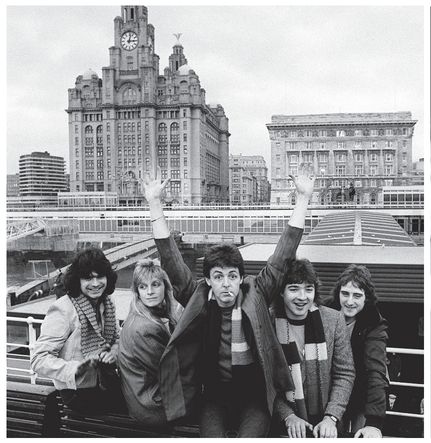

Paul poses with the final line-up of Wings in front of the Royal Liver Building, Liverpool, 1979. From left to right are guitarist Laurence Juber, Linda, Paul, drummer Steve Holley and guitarist Denny Laine.

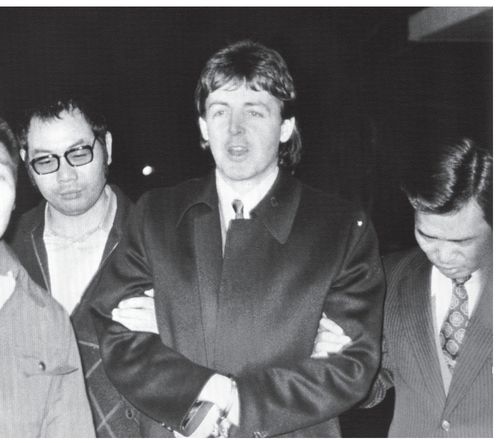

When Paul took Wings to Japan in January 1980 he foolishly brought marijuana with him in his luggage. Arrested at Narita Airport, McCartney is seen in handcuffs being taken to Kojimachi Police Station where he spent nine nights in a cell.

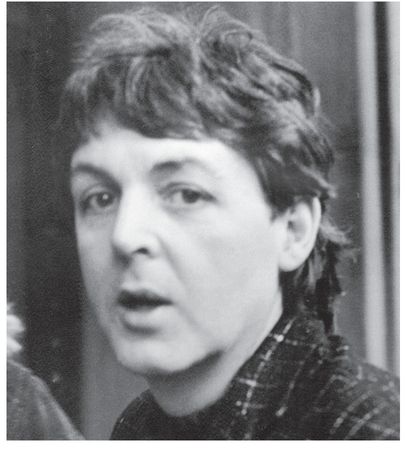

John Lennon was murdered in New York on the evening of 8 December 1980. The next day Paul went to work at AIR Studios in London. He is seen speaking to journalists about the death of his friend as he leaves AIR. ‘It’s a drag, isn’t it?’ he asked newsmen.

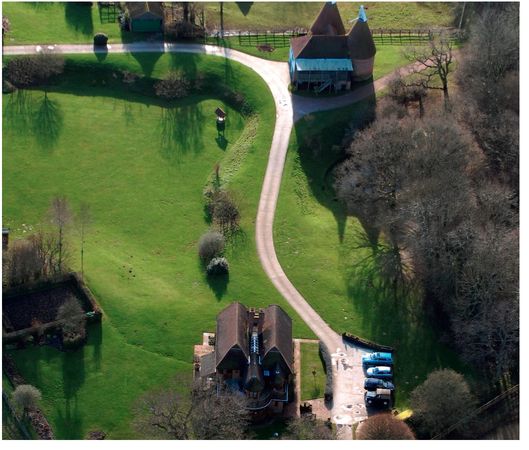

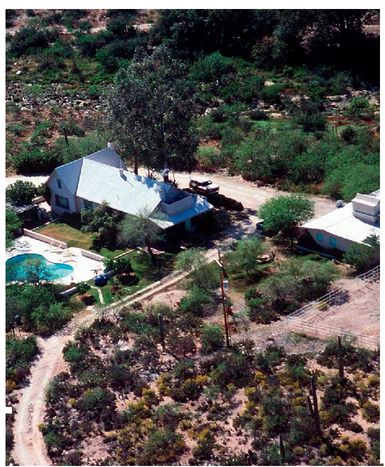

In the early 1980s Paul bought Blossom Farm adjacent to his original Sussex retreat, Waterfall, and had a new family home built. The house (bottom of picture) is now the centre of a vast, 1,000-acre private estate.

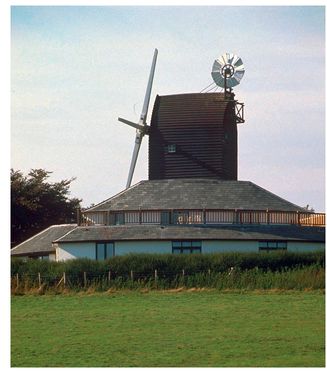

To enable him to spend time at home with the family in Sussex, Paul bought a nearby windmill, Hog Hill Mill, and had it converted into a recording studio.

The 1984 movie Give My Regards to Broad Street proved one of the biggest blunders of Paul’s career. any friends were given parts in the picture. Here Paul and Linda are seen in costume with Ringo Starr and his second wife Barbara Bach.

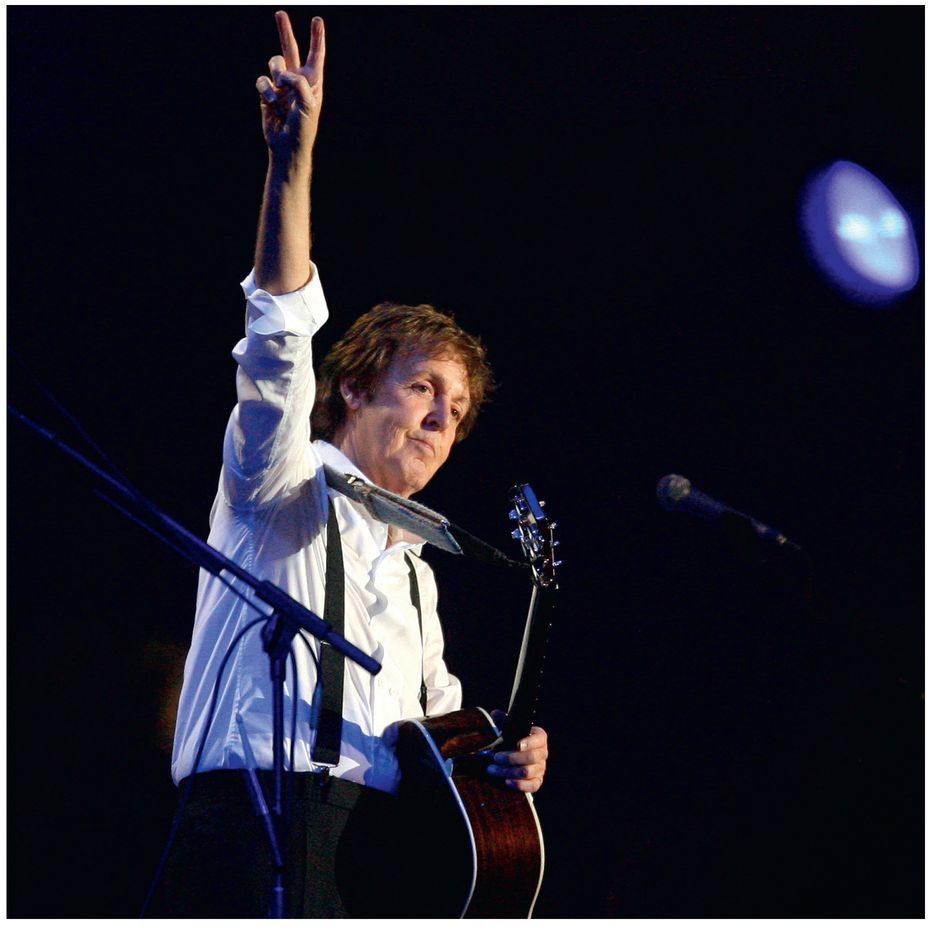

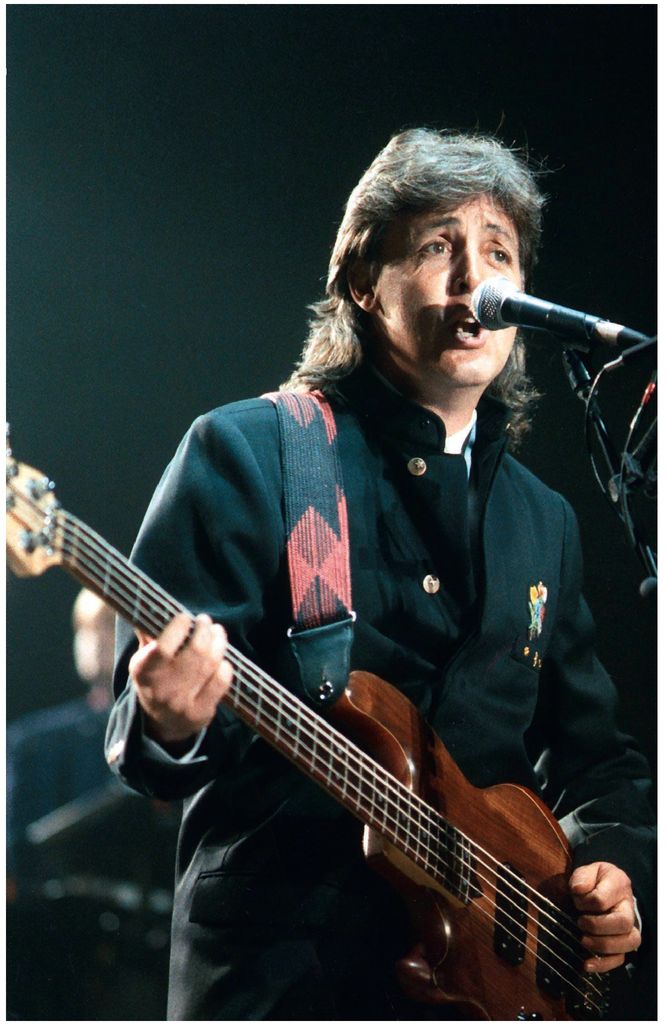

After ten years off the road, McCartney returned to touring in 1989, aged 47, with a show that was 50 per cent Beatles material.

Paul branched out into orchestral composition in 1991 with his Liverpool Oratorio. Here he is celebrating the success of the première at Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral with his co-composer Carl Davis and soloist Dame Kiri Te Kanawa (far left).

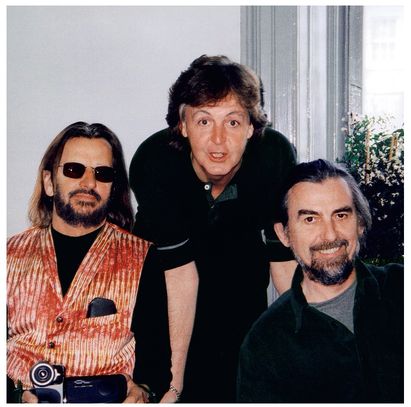

In the mid-1990s, the three surviving Beatles reunited for the Anthology project, recounting the story of the band for a TV series and book, and recording two ‘new’ Beatles songs, the disappointing ‘Free as a Bird’ and ‘Real Love’.

In March 1998, Paul and Linda went to Paris with their children Heather, James and Mary (seen left to right with their parents) to support their youngest, Stella, at her latest fashion show. Linda’s cropped hair was a sign of the treatment she had been receiving for breast cancer. A month later she was dead.

Linda McCartney died here at the McCartneys’ ranch outside Tucson, Arizona, on 17 April 1998. She was 56.

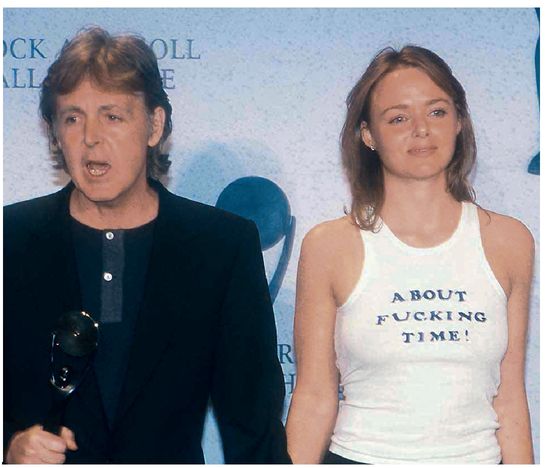

Stella McCartney makes it plain that, in her opinion, it’s about time Dad was inducted into the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist. New York, March 1999.

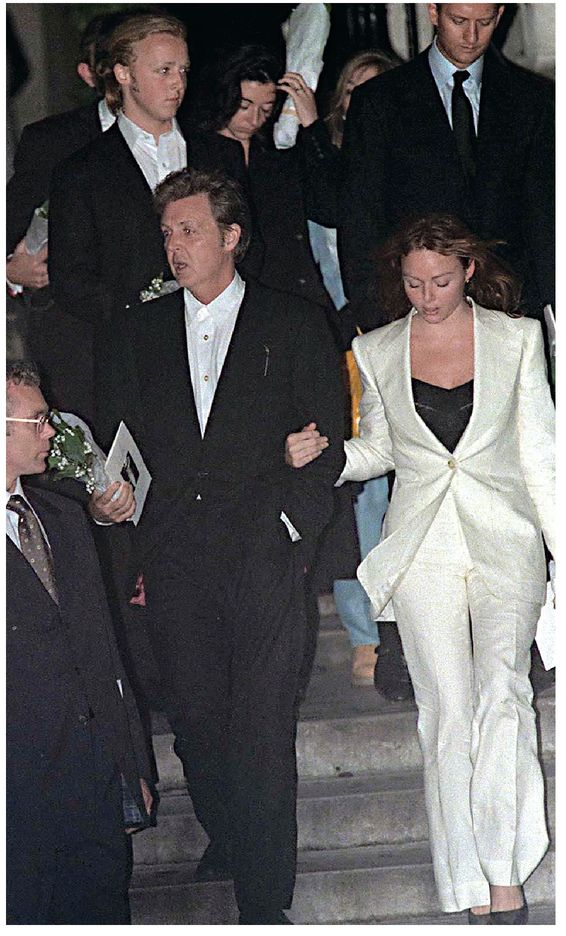

Sir Paul McCartney (knighted 1997) organised two memorial services for his late wife. Here he leads children Stella, James and Mary out of St Martin’s-in-the-Fields, London, on 8 June 1998.

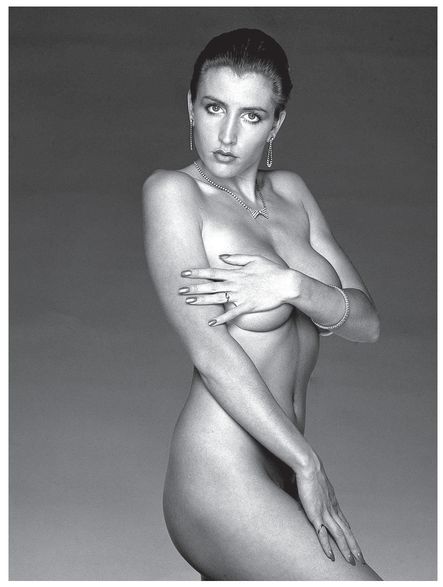

While still mourning the death of Linda, Sir Paul attended an awards ceremony in London in May 1999, where 31-year-old Heather Mills caught his eye. Here is Heather during her earlier career as a ‘glamour’ model.

Sir Paul and Heather Mills announced their engagement in July 2001, posing for photographers outside the musician’s London home. Despite a rocky courtship, they married the following June. Heather was 34; Paul was a week shy of 60.

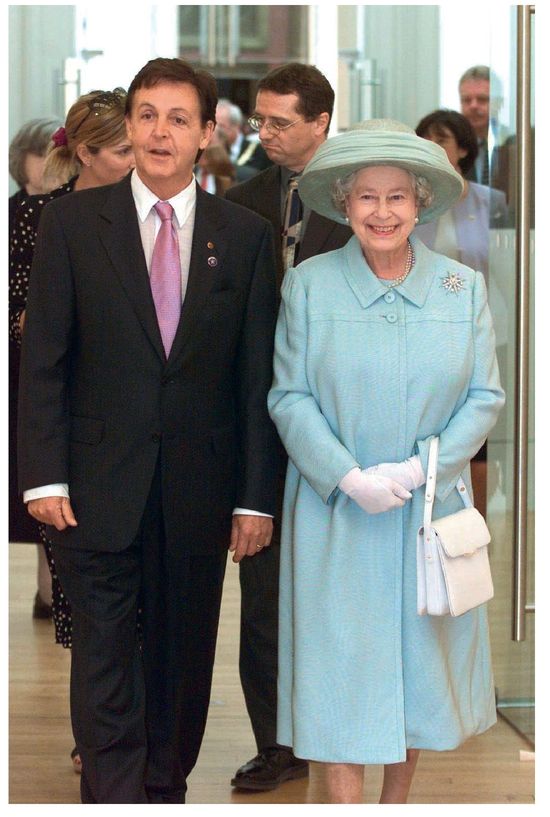

Over the course of his career Sir Paul has had many occasions to meet his monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, developing a warm relationship with Her Majesty. Here he shows the Queen around the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, May 2002.

The divorce of Sir Paul and Heather Mills McCartney was acrimonious. At the culmination of the case, Heather tipped a jug of water over Sir Paul’s solicitor Fiona Shackleton, who is seen leaving the Royal Courts of Justice with her client on 17 March 2008, her hair still wet.

Immediately after the divorce judgment, Heather Mills addressed the media at the entrance to the Royal Courts of Justice. She said she was satisfied with her £24.3 million settlement, but she had asked for much more.

In June 2008 Sir Paul returned to Liverpool to help the city celebrate its year as European Capital of Culture. He is seen here at a fashion show at LIPA, his old school, now a performing arts institute, with son James and Beatles widows Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison.

Since his divorce from Heather Mills McCartney, Sir Paul has spent much of his time in the company of the American Nancy Shevell. Here they are in Paris, October 2009.

With John Lennon and George Harrison gone, it has fallen to Sir Paul McCartney to carry the Beatles torch. The spectacular shows he gives around the world are emotional celebrations of the greatest band in the history of popular music.