Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 20. The First Experiment

KEEPER MCNAUGHTON entered William Kemmler's cell at five o'clock on the morning of August 6, 1890, turned a key on an iron lighting fixture, and struck a match to light the gas jet. By the flickering light, the prisoner ate a breakfast of dry toast and coffee, then combed his beard and wavy brown hair. He carefully stepped into his favorite yellow patterned trousers, then put on a white linen shirt, a dark gray coat and vest, and a black-and-white checked bow tie. The prisoner dressed, one reporter noted, "as carefully as if he were going to a ball."1

Kemmler collected his worldly possessions—Bible, pictorial Bible primer, writing slate, Pigs in Clover puzzle—and placed them on a small stand, along with his last will and testament. He left the items to his friends in the prison: The Bible primer would go to Mrs. Durston, the Bible to Keeper McNaughton, the slate to Chaplain Yates, the puzzle to Reverend Houghton. Just before six the chaplain, the minister, and the keeper crowded into his cell. They were joined by Joseph Veiling, a deputy sheriff from Buffalo who had befriended Kemmler in the process of guarding him before and during his trial the previous year. Veiling produced a pair of clippers, and the prisoner reluctantly allowed the hair at the crown of his head to be shorn very close. Then Veiling split the seam on Kemmler's trousers just below the waistband. When these physical preparations were completed, the four men turned to the spiritual. They got down on their knees and began to pray.

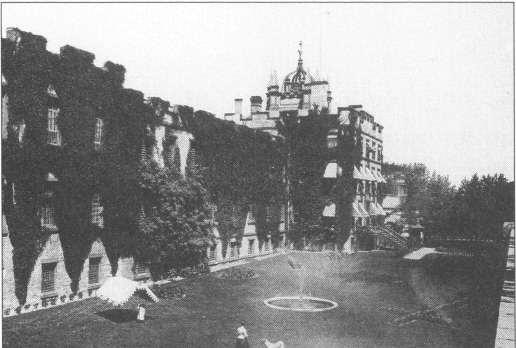

AT THE GATES of the prison a crowd of 1,000 people gathered under a cloudless morning sky Although the date of the execution was kept secret, all of the witnesses had arrived in town the day before, leading to speculation that Kemmler's execution was imminent. The platform of the New York Central Railroad Station across the street from the prison was filled to capacity. A few intrepid souls climbed trees, and the World reporter had constructed a special platform twenty feet up a telegraph pole. But these lofty perches only afforded a better vantage on the prison's fanciful turrets and ivy-covered walls, for the death chair was hidden in a basement cell. In a dimly lit freight room next to the train station, dozens of telegraph operators—sent up from New York City by Western Union just for the occasion—sat at makeshift tables, ready to relay the news of William Kemmler's historic death.

Auburn prison in 1890. Kemmler's cell and the death chamber are in the basement to the left of the entrance. The woman in the foreground may be the warden's wife, Gertrude Durston, accompanied by her English mastiff.

Starting a little before six, well-dressed men in groups of two or three began to emerge from the Osborne House, the local hotel, and walked briskly toward the prison. The men forced passage through the throng at the gate and presented themselves to the guards, who escorted them to the warden's parlor. Durston was pacing the room, angry that the witnesses were late in arriving. He needed the execution to be over by seven, so that the steam engines being used to power the dynamos could begin their usual work of running machinery in the prison's factories. Finally, at twenty past six, the last witnesses appeared, and the warden led them down an iron spiral staircase to the prison basement and into the death chamber.

When the machinery was first installed in April, the electric chair and the switchboard had been in the same room, but at the beginning of August the warden decided to move the chair to an adjacent room, while leaving the switchboard in its original place. His purpose, apparently, was to shield the identity of the man who threw the switch. Formerly the keepers' messroom, the new death chamber was about eighteen by twenty-five feet. Two iron-grated windows, partially covered by Virginia creeper ivy, looked out toward the crowds at the main gate. The death chair sat at the center of one end of the room.2

Wooden chairs were arrayed in a half-circle around the electric chair, and the witnesses took their seats. Despite the provision of the law prohibiting newspapers from publishing details of executions, the warden had invited two wire service reporters, one from the Associated Press and another from the United Press. Alfred Southwick—now referred to as the "father of the electrical execution law"—was in the room, as was Dr. Fell. A few men were notable by their absence. Harold Brown had not been invited, and Elbridge Gerry turned down his invitation in favor of a cruise with the New York Yacht Club. Edison did not attend, nor did his chief electrician, Alfred Kennelly, who a year earlier had expressed a wish to do so.3

Of the twenty-five official witnesses, fourteen were physicians. They included the editor of the Medical Record; the head of the state's Board of Health; a deputy coroner from Manhattan (invited because he had autopsied many men killed in electrical accidents); and the coroner who autopsied Lemuel Smith after his 1881 death in the Buffalo arc lighting plant. Dr. Carlos MacDonald, who had been the state's electrocution expert for nearly a year, served as one of the official execution physicians. The other was Dr. Edward C. Spitzka, the current president of the American Neurological Association.4

When everyone was seated in the room, Durston called aside his two official physicians. Astonishingly, the warden had not yet decided how long the prisoner should be subjected to the current, so he asked the doctors for advice.

"Fifteen seconds," Spitzka told him.

"That's a long time," said the warden, who feared burning Kemmler.

"Well, say ten seconds at least," MacDonald offered.

It was agreed that Spitzka would decide when to turn on the current and when to turn it off. He asked if anyone had a stopwatch, and MacDonald pulled one from his coat.5

Warden Durston abruptly left the death chamber and walked down the hall to Kemmler's cell. He greeted the prisoner and the ministers, then read the death warrant. "All right, I am ready," Kemmler said. He bid good-bye to Keeper McNaughton, who declined to be present in the death chamber. The prisoner fell into step behind the warden, the ministers followed the prisoner, and Sheriff Veiling brought up the rear. The execution procession was brief, requiring just a few steps down a hallway and into the death chamber.

The witnesses had been whispering nervously among themselves, but they fell silent as the warden and the prisoner entered the room. Kemmler walked toward the death chair, then paused, uncertain as to whether he should sit in it. He peered at the warden's face, like an actor uncertain of his cue.

"Will some gentleman give me a chair?" the warden asked. A witness pushed a common kitchen chair into the circle, and the warden placed it in front and a little to the right of the death chair, facing the witnesses. He pulled another chair next to it. He and Kemmler sat side by side facing the witnesses, the warden's arm over the prisoner's shoulder.

"Now, gentlemen, this is William Kemmler." The condemned man bowed slightly and looked around the arc of faces as if expecting greetings. No one spoke. The warden's hands and voice trembled. "I have just read the death warrant to him and have told him he has got to die." He turned toward Kemmler: "Have you anything to say?"

Kemmler's face brightened. He started to stand, then decided to remain seated. His feet were set wide on the stone floor, a hand on either knee, elbows akimbo. "Well, I wish everybody good luck in the world," he said in a deliberate voice. "I believe I am going to a good place."

"Amen," said the ministers.

At a nod from the warden, Kemmler stood. "Take off your coat, William," Durston said. Kemmler slipped off the coat and folded it neatly over his chair. The witnesses could see the slit that Veiling had cut below the waistband of his trousers. The warden bent down and began drawing the tail of Kemmler's shirt through the hole and cutting it off with scissors, dropping the scraps to the floor. When he was finished, a patch of skin at the base of the prisoner's spine was exposed to the warm, damp air. Durston motioned to the prisoner. Kemmler turned and lowered himself into the electric chair.

ON THE SECOND FLOOR of the east wing of the prison—more than 1,000 feet from the death chamber—was the Westinghouse dynamo, which was under the care of a Rochester electrician named Charles Barnes. Attached to the dynamo were wires made by the Edison Electric Company The wires, insulated in rubber and affixed to glass and porcelain insulators, ran out the window, over the roof, around the prison's ornamental dome, down the front wall, through a basement window, and into the switchboard room, which was under the direction of an electrician named Edwin F. Davis. The switchboard held two voltmeters, an ammeter (for measuring amperage), a bank of twenty incandescent lamps, and two jaw switches—metal bars eighteen inches long that swung in an arc of 180 degrees, from open to closed. The first switch allowed current to flow to the lamps, which were used, along with the meters, to gauge the strength and steadiness of the current. The second switch sent the current through wires that led to the adjoining room, where the electric chair was located.

Kemmler sat in the chair in a natural, easy posture. The warden had decided not to use the footrest, so Kemmler's feet rested on the floor. He lifted his arms high to allow the chest straps to be wrapped around him. The warden's hands trembled so much as he started to fasten the prisoner's arms that he could hardly thread the straps through the buckles. "It won't hurt you, Bill. It won't hurt you at all," said the warden, perhaps offering reassurance more to himself than to the prisoner, who did not appear to need it.

"Don't get excited, Joe," Kemmler said when Veiling began to fumble with the straps. "I want you to make a good job of this."

When the arm, leg, and body straps were cinched tight, Kemmler was completely immobilized. Durston pushed the rubber cup of the lower electrode through the hole in the back of Kemmler's trousers, and the spring mechanism held it tight against his spine. Durston slid the other electrode down against the ragged tonsure on Kemmler's head.

The prisoner moved his head from side to side, to show that it was not snug. "I guess you'd better make that a little tighter, Mr. Durston," he said, and the warden granted the request.

Durston affixed the leather mask, which pulled Kemmler's head hard and tight against a rubber-covered cushion on the chair's back. It covered the prisoner's chin, forehead, and eyes and smashed down his nose, but it left his mouth exposed.

Dr. Fell stepped forward with a syringe and soaked the sponges with a saltwater solution to lower resistance and prevent burning. Dr. Spitzka said, "God bless you, Kemmler," then nodded to the warden.

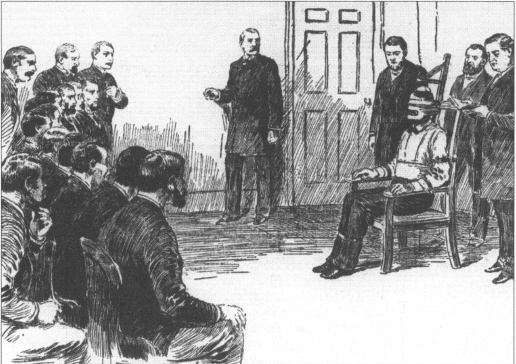

The Kemmler execution, as pictured in the New York Herald. The switchboard room was behind the door.

Durston edged over toward the door leading to the switchboard room.

"Good-bye, William," he said.

"Good-bye," came the muffled response from the chair.

DURSTON RAPPED TWICE on the door, a prearranged signal. The dynamo had been humming smoothly for several minutes, sending more than 1,000 volts of electricity through the switchboard. At Durston's signal, someone in the switchboard room—his identity was never revealed, but it might have been one of Kemmler's fellow convicts—closed the switch, diverting the current into the electric chair.

Kemmler gave a quick, convulsive start. His mouth twisted into a ghastly grin. Every muscle in his body contracted, straining against the leather straps. His right index finger doubled under with such strength that the nail cut into the palm and blood trickled out onto the arm of the chair.

Dr. Spitzka tiptoed to the chair and stared intently at the face of the bound figure. After seventeen seconds, Spitzka cried, "That will do! Turn off the current. He is dead." Another voice echoed, "Oh, he's dead."

The warden rapped on the door to the switchboard room, and the current to the death chair was cut off. At the switchboard, Edwin Davis pressed a button that rang a bell in the dynamo room, and the dynamos were shut off. Kemmler's muscles relaxed, and he slumped against the straps. The head electrode was removed.

"Observe the lividity about the base of the nose," Dr. Spitzka said. "Note where the mask rests on the nose—the white appearance there." The other doctors gathered round and pressed their fingers against Kemmler's face, noting the play of white and red when the fingers were removed. The hue of Kemmler's skin, Spitzka said, was "unmistakable evidence of death."

Electrical execution had been quick, clean, and painless, just as its advocates had argued. "This is the culmination often years work and study," Southwick proclaimed. "We live in a higher civilization today."

HE SPOKE TOO SOON. A cut on Kemmler's hand was dripping rhythmic pulses of blood. One of the witnesses shouted, "Great God! He is alive!" Another said, "See, he breathes!"

And he did. Kemmler's chest heaved, and from his mouth came a rasping sound, growing quicker and harsher with each suck of breath. A purplish foam from his lips splattered onto the leather mask. Saliva dripped from his mouth and ran in three streams down his beard and onto his gray vest. The chest straps squeaked as he struggled for breath, and he groaned, an animal cry that witnesses found impossible to describe. His whole body shook and shivered.

"Turn on the current! Turn on the current!" Someone shoved the electrode back down against Kemmler's skull. The warden signaled to the switchboard room, and the switchboard room signaled to the dynamo room, where the operators struggled to restart the Westinghouse machine. More than two minutes after the electricity had been cut off, the witnesses heard the thunk of the switch from the next room, and the current flowed.

Once again Kemmler's muscles contracted, his body rising up, rigid as a statue. This time there would be no mistake. The current stayed on for between one and two minutes—in the confusion, no one remembered to keep time.

The sponge of the back electrode dried out and burned away, allowing the bare metal disk to press sizzling against Kemmler's skin. At the head electrode his hair began to singe. The stench of burning hair and flesh filled the room.6

One witness turned aside and vomited. The United Press reporter fainted, and another witness propped him on a bench and fanned him with a newspaper. District Attorney Quinby rushed from the room in horror. Some turned away and hid their faces in their hands; others were so repulsed that they could not avert their eyes from the spectacle.

"Cut off the current," Spitzka shouted, and once again the wires fell dead. The smell of urine and feces mingled with the acrid smoke in the air. Dr. Fell doused a small fire that had started on Kemmler's coat near the back electrode. Another doctor held a bright light to Kemmler's eyes, and the optic nerve showed no response.

This time, Kemmler was dead. Fell made a small incision at the temple and drew off a blood sample for later testing. The warden loosened both electrodes and unbuckled the mask and the straps. There were livid blue marks where the mask had pressed Kemmler's face, and purple spots began to mottle his arms and neck. The witnesses filed out of the room, leaving Kemmler slumped in the chair. One of the witnesses—the sheriff of Erie County—was crying as he walked through the throng of reporters and townspeople at the gates of the prison.7