Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 17. The Electric Wire Panic

ALTHOUGH BROWN was pleased with the judge's ruling, the true goal of the Edison forces—banning alternating current or restricting its voltage—seemed no closer to reality. Westinghouse Electric and other lighting companies continued to resist New York law requiring burial of all wires, and accidents claimed more lives. Yet most people ignored Edison's warnings—until October 11, two days after the rejection of Kemmler's appeal, when one spectacular accident awakened the city to the terrors of electricity.1

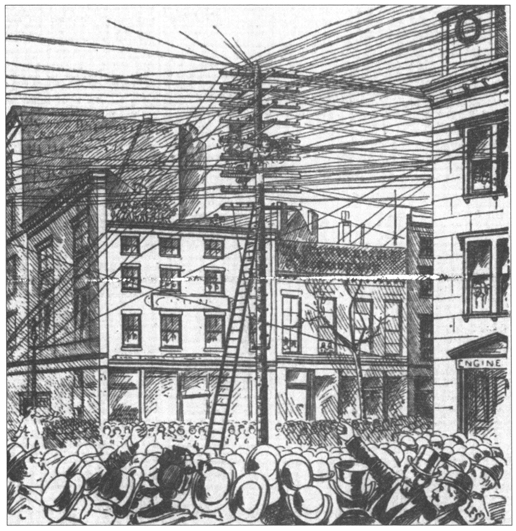

John Feeks, a lineman for Western Union, was a calm man of medium height, with a sunburned face and a bristly red mustache. At noon on October 11, his job took him to the intersection of Centre and Chambers Streets in downtown Manhattan, an area with one of the densest networks of wires in the city. The pole Feeks stood under bore fifteen crossbars—nine running north and south, six east and west—carrying more than 250 wires. Some of those wires were dead, and the lineman's task that day was to cut them away so that they would not interfere with those still in use. Because he would be working only with low-pressure telegraph wires, he chose not to wear rubber boots or gloves. He had a wire cutter on his belt and metal spikes on the insteps of his leather shoes. He grasped the pole with his hands, planted a spike in the soft wood, and stepped up the pole as easily as climbing stairs.

It was the lunch hour in Manhattan's busiest district, and the lineman's ascent drew a crowd. About twenty-five feet up, Feeks slowed to ease past the first cross-arm, which bore two thick cables carrying the pole's only electric light current. After that, it was a clear shot of twenty feet up to the pole's top, where the other fourteen crossbars bore their heavy burden of telegraph wires. Feeks stopped again at the lowest crossbar and stared straight up, plotting a route through the dozens of interlaced wires. After shifting to the north side of the pole, he poked his head through a small opening in the wires and drew his shoulders together as he squeezed through. Then he looked for the next gap in the weave. When none offered itself, he yanked the wires apart with his hand and hoisted himself through. In this way Feeks passed the first, second, third, and fourth crossbars, before arriving at the place where he had work to do. He wrapped his left arm around a crossbar and braced his left foot against a wire on the crossbar below. His right leg dangling free, he drew the pliers from his belt and reached out to snip a wire. As he did so, he lost his balance and grasped a wire with his right hand to steady himself.

As far as Feeks knew, the only danger was falling, because the telegraph wires normally carried too little current to pose a risk. But somewiiere, blocks away, an alternating-current light wire had crossed the same telegraph wire Feeks held in his hand. As the wires blew in the wind, the dead telegraph wire cut through the insulation on the light wire. High-voltage current diverted from its charted course and surged down the telegraph wire, into Feeks's right hand, and out his left foot. His body went tense, his right arm quivered, his mouth opened but emitted no sound. Feeks's head reared up, and his throat came to rest on the live wire. A tiny blue flame played around his right hand and his left foot, and small puffs of smoke drifted away on the wind.

The small group of men who had watched Feeks's ascent screamed, and immediately every face on the street turned and looked up to see a man trapped like a fly in a web of wires. Before long, thousands of people filled the rooftops and blocked the streets and the approach to the Brooklyn Bridge. World reporter Nellie Bly, just a few days from setting off on her famous globe-girdling trip, pressed her way through the crowd in time to see the wires burn into the lineman's flesh. "The hand ceases to quiver," Bly wrote, "and a dark-red stream gushes from the wrist. Now it springs from the throat, spotting the pole and dripping down on the heads of the fleeing crowd."

The death of lineman john as illustrated in the New York World.

After forty-five minutes another lineman, wearing rubber boots and gloves, climbed the pole, tied a rope around Feeks's waist, and tossed the other end over a crossbar and down to the street, where more Western Union men took up the slack. As the lineman clipped the wires that ensnared Feeks, they whipped to the street and sent the crowd running again. When the last wire was severed, Feeks swung free and was lowered slowly to the ground, doubled up, his hands touching his feet. "Killed first, cut afterwards, then roasted," Nellie Bly reported, "not by heathens, but by a monopoly. All at mid-day in the streets of New York."2

Electricity had killed other men in New York, but there had never been anything like the death of John Feeks. It was a shared trauma. Thousands witnessed the bloody spectacle in person, and hundreds of thousands more read about it and saw the illustrations in the newspapers. The Tribune wrote that it had been more than a decade since the city had experienced "so many unmistakable indications of popular agitation and anger." In shops and homes, in streetcars and on street corners, the death was the main topic of conversation for days afterward. "Until Feeks was killed it was popularly supposed that an ordinary telegraph or telephone wire was harmless under all circumstances," the Sun observed, but that was before "a multitude of thousands saw7 a poor fellow roasted upon a gridiron of fire-spitting threads that had never before shown a sign of danger."3

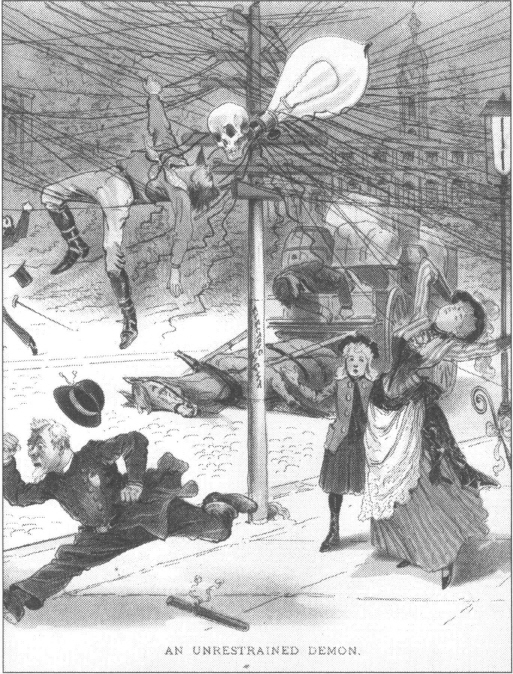

"Any moment may bring a similar horrible death to any man, woman or child in the city," the World warned.4

Panic-stricken building owners took the law into their own hands and chopped the wires running over their rooftops. According to the World, some people grew so terrified that they threw out their telephones, "as if the little wires which connect them went straight to the river of death."5

On the pole where Feeks died, a saloon keeper nailed a tin cracker box with a sign reading "Help the Victim's Widow," and within a few days the donations totaled more than $2,000.6

The day after Feeks died, Mayor Hugh Grant convened the Board of Electrical Control and ordered that all unsafe wires be cut down immediately Before the removal of wires could commence, however, George Westinghouse set his lawyers to work and scored a quick legal victory, persuading Justice George Andrews of the state supreme court to issue an injunction barring the city from touching the wires of Westinghouse's subsidiaries, the Brush and U.S. Illuminating companies. The World hinted at the all-too-plausible possibility of bribery, charging the judge with "ignorance or worse" and asking, "What influence was it which induced Judge Andrews to render so absurd a decision?"7

George Westinghouse suddenly appeared to be the man that Edison and Brown had long described: a cold-blooded villain denying the dangers of alternating current and risking lives for the sake of profits. "How ignorant or how deceitful, and how contemptible in either case, appear the assurances of safety with which the community has been mocked for years past," a newspaper editorial charged.8

THE TRIBUNE took this occasion to bemoan the "extraordinary condition of impotence to which the complicated machinery of civilization has reduced this community." It was an unusual admission, for Americans rarely paused to acknowledge that economic growth was taking a heavy toll in lives. In fact, more Americans were killed and maimed in the peacetime economy of the 1870s and 1880s than in the Civil War, and the most dangerous industries—railroads and coal mining—were the same ones that fueled the boom. Every year 1 out of 100 railroad brakemen died, along with 6 percent of the workers in some Pennsylvania coal fields. The danger was not inevitable. In late Victorian England—hardly a model of the compassionate state—the rate of railroad worker deaths was much lower, thanks to more stringent regulation. The United States, on the other hand, did not begin to adopt effective safety regulations until after 1900. In the 1880s, the government and the courts showed little interest in protecting the lives of workers.9

Electricity accounted for fewer than 1 percent of the accidental deaths in New York in the late 1880s. If the raw numbers were the guide, the city should have been in a panic over the many things—elevator shafts, street railways, illuminating gas—that killed far more people than overhead wires. But electricity was different. It was new and mysterious, a force of life as well as a cause of death. Electricity held people in thrall, and it was a short step from awe to dread.10

This illustration, which appeared in Judge magazine shortly after Feeks's death, captured the widespread fear that no one was safe on the streets of New York.

The death of John Feeks showed Americans that the danger was no longer restricted to workers in a few industries. Electric wires brought the terror home. "Death does not stop at the door," one expert said, "but comes right into the house, and perhaps as you are closing a door or turning on the gas you are killed. It is likely that many of the cases of sudden death we hear of from heart disease may come about this way." "There is no safety, and death lurks all around us," another expert warned. "A man ringing a door-bell or leaning up against a lamp post might be struck dead any instant."11

With word that judicial intervention once again blocked removal of dangerous wires, the public's impotence turned to rage. A population accustomed to violent death, meek before the corrupt alliance of government and business, suddenly found its voice. One marker of the depth of public anger was the unanimity of newspaper opinion. Joseph Pulitzer's crusading World, as expected, concluded that "men's lives are cheaper to this monopoly than insulated wires." More surprising were the reactions of the Times and Tribune, which usually sided with corporations and private property: Both papers urged that the dangerous light wires be cut down, and that the companies' officers be indicted for manslaughter. The Times claimed that the Board of Electrical Control was as responsible as the electric companies. If the board's members were convicted of murder in Feeks's death, the newspaper wrote, they would receive the death penalty and "the deadly current might be put to good use."12

Electrical execution was never far from people's minds during the wire panic. The grisly spectacle of Feeks's death accomplished in forty-five minutes what Edison and his allies had been trying to do for more than a year: It convinced the public that the Westinghouse current was terrible and deadly.

The World drafted Harold Brown as its in-house expert and sent a reporter to accompany him as he measured leakage from alternating-current wires. The Times quoted a lengthy tirade by Brown against alternating current, which included the reminder that "a certain electric light syndicate"—Westinghouse—"has recently acquired the Brush and United States Illuminating Company's stations," the two main offenders in the current string of deaths. The electric wire panic rehabilitated Brown's reputation. A magazine enlisted him to write an article on electrocution and the dangers of alternating current, and an electrical journal asserted that he "has done his utmost, either from pure philanthropy or the love of gain, to bring home to the public a possible danger." At this point few seemed to care that Brown had conducted secret deals and abused his contract with the state in order to malign the Westinghouse company. Brown slipped comfortably into the guise he had tried to wear since the summer of 1888: that of an altruist warning the public about a lethal threat.13

During the panic, Edison consulted with Brown several times, asking for statistics on accidental deaths and plotting strategy on how best to turn the publicity to their advantage. An investor in the Edison system took an optimistic view of Feeks's death, telling Edison that "there never has been such a grand occasion" to attack alternating current. "A communication from you to the principal newspapers" promoting direct current "would greatly benefit our companies … and boom the stocks," the man wrote.14

In this regard, Edison needed little prompting. When a reporter from New York appeared at his doorstep not long after Feeks's death, Edison greeted him with a question: "Have they killed anyone there today?" With his gray hair and gleaming gray eyes, Edison was half prophet of doom, half reassuring grandfather. He predicted that more innocents would die soon, and that the problem would not stop when the wires were buried. "When under ground," he warned, "the dangerous current will creep into your house, and will come up the manholes." Although eager to sow fear, Edison also offered a path to safety. "Is there not a law in New York against the manufacture of nitro-glycerine within the [city] limits?" he asked. "Well, there must be one against deadly currents. Let the Mayor keep the pressure reduced to 700 volts continuous current and to 200 alternating." These restrictions, Edison said, could be enforced "under police regulation, just as steam boiler pressure is."15

The inventor soon earned an even bigger forum. The North American Review, one of the nation's most influential opinion journals, asked Edison to contribute an essay, published in November as "The Dangers of Electric Lighting." It opened with an invocation of Feeks's death: "If the martyrdom of this poor victim results in the application of stringent measures for the protection of life," Edison wrote, "the sacrifice will not have been made in vain." He said the tragedy could have been avoided had authorities heeded his earlier warnings. Alluding to his dog-killing experiments, he wrote, "I have taken life—not human life—in the belief and full consciousness that the end justified the means." These tests had shown that the passage of "alternating current through any living body means instantaneous death."

"Burying these wires," Edison believed, "will result only in the transfer of deaths to man-holes, houses, stores, and offices, through the agency of the telephone, the low-pressure systems, and the apparatus of the high-tension current itself"

"I have no intention, and I am sure none will accuse me, of being an alarmist," Edison said, having just raised the specter of people being shocked dead in their homes as they picked up the telephone. He said he was simply calling attention to an unseen danger and proposing a remedy. His own low-pressure system was commercially successful and perfectly safe. He therefore advocated "rigid rules for the restriction of electrical pressure," although he would have preferred to go a step farther: "My personal desire would be to prohibit entirely the use of alternating currents. They are as unnecessary as they are dangerous."16

IN LATE NOVEMBER and early December, three more Manhattan men died in electrical accidents. Two of the victims were light company employees, but it was the third death that further stoked the public's rage. While closing up shop for the night, a clerk in an Eighth Avenue dry-goods store picked up a tall metal display case to move it from the sidewalk into the store. The case touched a low-hanging Brush arc lamp, and the clerk fell dead from the shock. It was exactly the type of tragedy Edison warned about: a private citizen struck dead on the sidewalk while performing the routine tasks of life.17

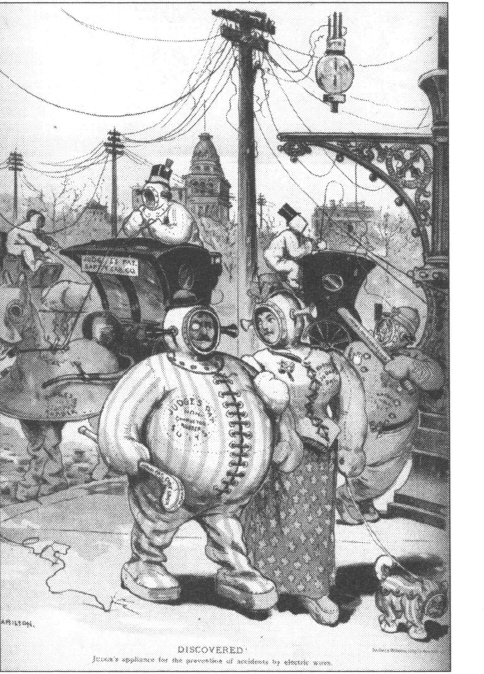

"Mr. Edison has since declared that any metallic object—a doorknob, a railing, a gas fixture, the most common and necessary appliance of life—might at any moment become the medium of death," the Tribune warned. New Yorkers took heed. Some refused to have doorbell wires strung through their homes, fearful that the touch of a button might bring instant death. The Evening Post observed, "One scarcely ventures to put a latch key into his own door." An electrical journal branded such fears "lunatical" and "nonsensical," but the public was not reassured. The Tribune and other New York newspapers endorsed Edison's call for voltage limits, as did papers in other states. Referring to Edison as "the highest authority on the matter of electricity," a South Carolina paper called for limits on voltage. "Mr. Edison is right in his position that electric tension should be regulated by law," another paper said. "The only reasonable solution of the whole problem lies in making every electric wire safe, not because it is insulated but because in its nakedness it carries no death-dealing power."18

The movement gained ground in New York as well. The World pointed out that the city's Board of Health had the power to remove from the streets anything "dangerous to life or health." At the World's request, Harold Brown filed a petition with the health board asking it to prohibit "any current liable to cause death or injury to human life." The city health department conducted tests at a local light company and found that even new wires leaked, exposing the public to grave dangers. The board passed a resolution calling for limits of 250 volts on alternating current, but it deferred enforcement to the electrical board. "In the estimation of Thomas A. Edison," the World said, such limits would "afford a guarantee of safety not promised by any other plan." Mayor Grant rejected the plan, fearful of violating Judge Andews's injunction against the removal of the wires and worried that such voltage limits would leave Edison as the sole light company standing. "I will not vote for such a monopoly," Mayor Grant said.19

The health board's plan failed, but it terrified the alternating-current forces. Facing removal of their wires or even voltage limitations, they embraced the remedy that they had fought bitterly only a few months before: the burial of their wires. George Westinghouse wrote "A Reply to Mr. Edison" for the North American Review, insisting that alternating current would be perfectly safe if tucked under the streets. This tardy concession did not appease the public. Feeks and a dozen other men were dead, the World charged, only because "the Electric-Light Companies scorn the law, defy its officers and twiddle their fingers at a helpless public."20

On December 13, two months after the death of John Feeks, the state supreme court dissolved the injunction against removal of the wires and issued a ruling harshly condemning the light companies: "When they claim that the destruction of these instruments of death, maintained by them in violation of every duty and obligation which they owe to the public, is an invasion of their rights of property, such claim seems to proceed upon the assumption that nothing has a right to exist except themselves."21

Judge magazine offered the tongue-in-cheek proposal that rubber suits offered the only means of protecting oneself (and one's animals) from the dangers of electric shock.

Time had run out for the Westinghouse lighting interests in New York. The electrical board ordered them to shut off their current by eight o'clock the next morning, and the removal of lines began at precisely half past nine. The Department of Public Works hired twenty-five men, equipped them with rubber gloves and insulated wire shears (known as "nippers"), and divided them into four gangs. Each gang started at a central station and followed the wires radiating from it, searching for violations: bad insulation, unauthorized poles, lamps hanging too low, wires affixed to telegraph poles or elevated train platforms. When they spotted problems, a lineman climbed the pole and snipped the wires, and then one of his fellows went at the pole with an ax. The crews toppled twenty-three poles and stripped nearly 50,000 feet of wire on the first day, a Saturday. Eager to continue, they started in again the next morning, although the World noted that "churchgoers expressed disapprobation of the Sunday work."22

New Yorkers took gleeful pleasure in this assault on private property. After the carnage of the previous months, the attack on the poles became cathartic. Crowds gathered to cheer and watch the chips fly as workers used axes to fell electric light poles. "Destruction of Property Goes Merrily On," read a headline in the staid Times. When the work continued on Christmas Eve, the newspaper described "the music of the axes and nippers" as "fitting accompaniment to the spirit of holiday merrymaking." The destructive frenzy tailed off on December 30, by which time more than 1 million feet of wire—a quarter of the city's total—had been stripped from the streets.23

Without wires, however, there was less light. The companies could lay new wires underground, but that would have to wait until the spring thaw unlocked the ground and the laying of conduits resumed. The only light company unaffected was Edison Illuminating, whose wires had always been underground. But Edison did not light the streets. A few months earlier, Brush, United States Illluminating, and a few other companies sent current to more than 1,000 arc lamps that threw a harsh white glare on the city's night life. On New Year's Eve 1889, all of those lights were off. Early in the evening the interior lights of stores and saloons threw a glow onto the sidewalks, but when businesses closed, the streets grew black. New Year's revelers lit candles and lanterns and picked their way along slushy streets, islands of light moving cautiously through the black night. A new decade had begun, but to many New Yorkers it appeared that the city had taken a step back into a gloomy past.24