Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death - Mark Essig (2005)

Chapter 16. Pride and Reputation

WHEN THE Harold Brown scandal broke in New York in August 1889, Edison was an ocean away. Not long after he testified at the Kemmler hearings, he and his wife, Mina, boarded the steamship La Bourgogne, bound for the Universal Exposition in Paris.

Edison was grandly received at the world's fair. French newspapers hailed him as "His Majesty Edison" and "Edison the Great," and when he ventured onto the street, crowds gathered to cheer and stare. In their rooms at the Hotel du Rhin, floral offerings to Mina crowded every piece of furniture, and assorted European royalty dropped in to record their voices on Edison's personal phonograph. Edison also found himself besieged by visitors of lower rank; many of them, he complained, were crackpot inventors who begged him to "give the last touches to some lunatical invention of theirs." Mina found all the attention wearying. "We never get out as somebody is after him all the time," she wrote to her mother. Despite the complaint, Edison and his wife went out often, attending an incessant round of ceremonies and banquets in his honor. A special envoy of King Humbert of Italy named Edison a grand officer of the crown of Italy, and the French government raised him to the highest rank of the Legion of Honor.1

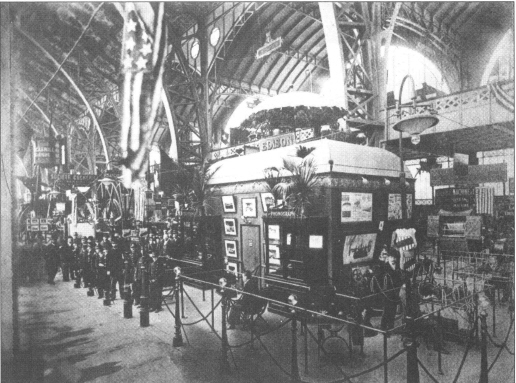

Part of the Edison exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1889.

Edison was not always gracious enough to return the praise. "What has struck me so far chiefly is the absolute laziness of everybody over here," he told an American reporter in Paris. "When do these people work?"2

The fruits of Edison's own labor were obvious. To advertise his products, he had purchased the single largest exhibit space at the fair, covering a third of the area allotted to American companies. The display featured many of Edison's inventions: telegraphs, motors, electric railways, telephones, batteries, electric pens, typewriters, phonographs, and a complete central power station that included dynamos, underground conductors, and meters. To guide visitors to his display, Edison lit a beacon: a forty-foot-tall model of an incandescent lamp, lit from within by 13,000 standard incandescent bulbs and sitting atop a twenty-foot pedestal. Twelve steps of multicolored bulbs led up to the top of the pedestal, which contained a niche with a bust of the inventor. Above the display, Edison was spelled out in lights.3

The inventor paused in his self-promotion to advocate another new electrical device: He spoke so glowingly about execution by alternating current that the French Academy of Sciences decided to investigate the matter (but ultimately retained the guillotine).4

Just outside Edison's Paris hotel stood a statue of Napoleon. As he passed by it each day, he might have recalled the time when the explorer Henry M. Stanley dropped by the Orange laboratory to hear the phonograph. After listening for a while, Stanley asked Edison whom he would choose if he could "hear the voice of any man whose name is known in the history of the world."

"Napoleon's," Edison answered briskly.

The pious Stanley replied, "I should like to hear the voice of our Saviour."

"Well, you know," said Edison, not a bit flustered. "I like a bustler!"5

As he basked in the adoration of Paris, the unmasking of Harold Brown revealed that Edison played a starring role in one of the strangest hustles in the history of American business.

IN 1888, when controversies over electrical execution first arose, Edison was asked his opinion about capital punishment in general. "There are wonderful possibilities in each human soul, and I cannot endorse a method of punishment which destroys the last chance of usefulness," he said. "I think that the killing of a human being is an act of foolish barbarity. It is childish—unworthy of a developed intelligence."6

Edison, however, had no qualms about helping to create a better way to kill. Arthur Kennelly became a true believer in the humanity of electrical execution, which he called "the signal of a rising civilization." Edison's support for the new method was more measured but nonetheless genuine. As he told the Sun, "I am not in favor of executions, but if they are to take place electricity will do the work, and it is more certain and perhaps a little more civilized than the rope."7

This assertion would have been equally true for any make of alternating dynamo, but Edison helped to ensure that Westinghouse machines would be used. Although he never directly explained why he participated in the conspiracy, his rivals claimed to know the reasons. George Westinghouse believed Edison's actions were economically motivated, an attempt to neutralize Westinghouse's technological advantage by imposing government regulations on alternating current. Bourke Cockran thought it was personal; at the Kemmler hearings he hinted that Edison's pique over Westinghouse's infringement of his incandescent lamp patents drove him to seek revenge. Both believed that Edison's relentless focus on the question of safety was merely a dodge for selfish motives.8

If Edison's only goal had been to regain his hold on the electricity market, he had more conventional avenues open to him. In 1886 Edison Electric had purchased American rights to one of Europe's best alternating-current systems, and Edison conducted experiments on similar equipment. Despite his vested interest in direct current, Edison could have manufactured both systems, gradually shifting from direct to alternating current. Given the power of the Edison name and his deep experience in the electricity business, he would have had a good chance of routing Westinghouse in head-to-head competition for the alternating-current market.9

Many voices within the Edison fold wished he would do just that. At a convention of local Edison companies in the summer of 1889, Edison affiliates voiced a desperate need for a new system that could compete with alternating current, something using "higher pressures and consequently less outlay of copper than that involved by the three-wire method. We earnestly appeal to the parent organization to supply these deficiencies." Instead of building a rival alternating system, Edison tried to develop a five-wire circuit, which proved too complex. A high-pressure direct-current system was equally balky and, Edison feared, too dangerous.10

Later in 1889 Edison consented to build an alternating generator—but he did not agree to sell it. He thought that if he built a system exactly like Westinghouse's, he could use it to show the inefficiency and danger of alternating current. "Our condemnation of our apparatus would carry with it condemnation of theirs," Edison said. "We are, of course, agreed that the Edison Company has no desire, and no intention of actually selling alternating apparatus for electric lighting, if they can possibly avoid it."11

In his opposition to alternating current, Edison was fully supported by Edward Johnson, his old friend and the president of Edison General Electric. Johnson explained that selling alternating equipment would "destroy the reputation of the Edison Company, which has, in a large measure, been built up on the safety and economy of the Edison apparatus."12

IN 1882, when a humane society representative had inquired whether electricity might offer a better way to kill livestock, Thomas Edison told her that "the alternating machine of Gramme would kill instantly."* At that point Edison had no possible economic motive for saying this; the Gramme machine was used exclusively for arc lights, which Edison did not make, and an alternating incandescent lighting system to rival his own direct-current system was still four years in the future. Edison had a genuine fear of alternating current based on the theory that its rapid back-and-forth motion did more damage to the body than the steady flow of direct current.13

The tests performed at Edison's laboratory in 1888 had confirmed that alternating current was more dangerous. In the fall of 1889, those results were further buttressed by Jacques Arsene d'Arsonval, one of the most eminent physiologists in Paris, whose reports on electrical safety were translated and published in American electrical journals. Edison kept up with d'Arsonval's research and shared it with the publie. "Let me read you part of an article by Mr. d'Arsonval, the greatest authority in France upon electrophysiology," Edison told a newspaper reporter in October. "He says:'... at a mean equal pressure alternating currents are much more dangerous than continuous currents.'"14

Safety had long been Edison's preeminent concern. When he first introduced electric light, he argued that it was safer than illuminating gas because it was less likely to cause fires and would not asphyxiate people in their sleep. When in 1882 Brush Electric introduced its storage battery electric lighting system—which sent high-voltage direct current into batteries in people's homes—the Edison company warned that introducing high voltage into homes was unwise. "If deaths happen from such contact with electric wires," Edison Electric's president wrote to the New York Times, "a storm of undiscriminating public indignation will attack all methods of domestic lighting by electricity."15

Even in 1889, Edison believed that the electrical industry was in a precarious state. Only a tiny fraction of American homes were wired for electricity, and electrical utilities were burdened with enormous debt. The powerful illuminating gas companies had improved their technology and cut prices in an effort to bury their upstart competitors. Electrical utilities had yet to prove that they could compete successfully with gas lighting. In Edison's view, accidental deaths might be a nail in the coffin of the electric lighting industry. As he explained, "If we ever kill a customer it would be a bad blow to the business."16

Edison's statement—in its concern for the business rather than the customer—may appear to neglect the human costs of electrical accidents, but business meant more than money to Edison. In 1886 his lawyers had proposed merging the English branch of the Edison company with the firm of Joseph Swan, with the new company to bear both men's names. Edison was outraged: "The company shall be called the Edison Electric Light Company, Ltd., or at least shall be distinguished by my name without the name of any other inventor in its title," Edison wrote. "I am bound by pride of reputation, by pride and interest in my work. You will hardly expect me to remain interested, to continue working to build up my new inventions and improvements for a business in which my identity has been lost."17

Edison ultimately agreed that the new company would be known as Edison & Swan United Electric, but his attitude toward the merger reveals what drove him. Although he would make the same amount of money regardless of the company's name, it was not simply a question of economics; it was one of "pride" and "identity." After years of passionate labor, Edison "tamed the thunderbolt"—as the reporters phrased it—and created a system that safely brought electric light into people's homes. Thanks to that achievement, the terms Edison and electricity became virtually interchangeable in the American imagination, as well as in Edison's own mind. He vowed to protect his own good name and the reputation of the light he had invented.18

WHEN EDISON RETURNED from Paris on October 6, 1889, n e received word that the U.S. Circuit Court had invalidated the paper-filament lamp patent—once owned by Consolidated Electric but by then controlled by Westinghouse—and dismissed Westinghouse's suit against Edison. (The other major lawsuit, in which Edison Electric was suing Westinghouse for violation of its basic lamp patent, was still unresolved.) Westinghouse planned to appeal this latest ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the lower-court decision nonetheless constituted an important victory for Edison.19

"Westinghouse simply grabbed fifty-four of my patents and started into business, saying that he could sell his manufactures cheaper because he did not have to pay out money experimenting," Edison told the New York Herald onOctober 7. He added, "Westinghouse used to be a pretty solid fellow, but he has lately taken to shystering."

The day the article ran, a top Edison lieutenant ran into Westinghouse over lunch and reported the encounter to his boss: "Mr. Westing-house remarked to me that he felt very much hurt by your calling him a 'shyster' in this morning's 'Herald.' He was really cut up about it."20

Rather than apologizing to his rival, Edison went on the attack, instructing his agents in Pittsburgh to gather all available information about Westinghouse's railroad air brake business. Since Westinghouse had invaded his territory in incandescent lighting, Edison considered turning the tables by striking at the heart of the Westinghouse empire. Although this plan was abandoned rather quickly, Edison soon found fresh grounds for assailing his rival.21

Three days after the decision in the patent case, a lineman for an electric company received a fatal shock atop a pole on Grand Street. In September two others had died in electrical accidents: A worker at East River Electric had lost his balance, grabbed a switchboard, and fell dead, and an Italian fruit vender slipped while cleaning the roof of his shed, fell against a wire owned by the United States Illuminating Company, and died. The deaths served as a reminder that the city was still festooned with dangerous overhead wires.

By the time of these deaths, the two firms with the most wires in the worst condition—United States Illuminating and Brush Electric Illuminating—were no longer independent companies; both had been acquired by Westinghouse Electric. This meant that most of the high-voltage overhead wires in New York City were under the control of George Westinghouse, who continued to resist efforts to remove them, make them safer, or place them in underground conduits.22

After the latest accidental death, Thomas Edison told the Evening Sun, "They say I am prejudiced, but if I had anything to say I would abolish the alternating current."23

SOME PEOPLE distrusted Edison's opinions on this matter because his money and his passion were tied up with direct current, but the same objection could hardly have been urged against alternating-current pioneer Elihu Thomson. Thomson feared alternating current nearly as much as Edison did, and he was just as outraged over the accidental deaths in New York and elsewhere. As the inventive mind behind the Thomson-Houston company, Thomson had sketched designs for alternating systems in 1885, but he delayed the work because he considered high-voltage alternating current too dangerous. Only after inventing and patenting a number of safety devices—such as fuses and "lightning arresters" to prevent dangerous shocks from reaching indoor wiring—did he consider the system safe enough to sell to the public. Unhampered by such concerns, Westinghouse had opened a large lead before Thomson-Houston entered the market. Despite the delay, Thomson believed his company had one clear advantage: It held the patents on all the important safety devices.24

As it turned out, those patents offered little leverage. Like the Edison and Westinghouse companies, Thomson-Houston made most of its money selling its dynamos, bulbs, and other equipment to utility companies, which then installed them and supplied light to customers. The manufacturing companies had little control over how carefully their equipment was installed. Most of the local utilities that bought the Thomson-Houston system did not purchase the safety equipment, and there were few governmental regulations that required them to do so. "In the general scramble for business there has been a neglect of proper precautions," Thomson explained.25

Thomson's private correspondence revealed his dismay. "The manner of installation in New York City is simply abominable," he wrote. The accidental deaths resulted from "gross carelessness and recklessness" on the part of the local lighting companies, and "it is only a wonder to me that fatal accidents are not more frequent." Even properly installed, however, such wires could not be safe, because "no insulation that has as yet been found is any too good." As Thomson saw it, the solution was to bury all of the wires used in heavily populated cities such as New York.26

Elihu Thomson

When the overhead wire battle heated up in the fall of 1889, some Thomson-Houston managers asked Thomson to pen an article reassuring the public about the safety of the firm's equipment. He refused: "I certainly shall not put myself in a position to be criticized as Mr. Edison has been criticized in what he has said about wiring, as only said in self-interest." Many of the Thomson-Houston systems in service—including many plants in New York—were nothing short of lethal, and Thomson would not defend them.27

When Thomson did issue a public defense of alternating current, it was couched in the most cautious of language. High voltages were necessary for the affordable transmission of energy, Thomson wrote in Electrical World, but the public needed to be protected through safety devices, better insulation, and the placement of wires in underground conduits. Thomson did not downplay the dangers of the current he sold: "Alternating current is much less safe than … continuous currents of equivalent potential."28

George Westinghouse never made a similar admission. At the end of 1888 he publicly stated that "pressures exceeding 1,000 volts can be withstood by persons of ordinary health." By late 1889 he admitted that alternating current could kill under some circumstances, but he still insisted that "there have been hundreds of cases in which momentary contact with an alternating current of 1,000 volts and over … has resulted only in painful shocks, unaccompanied by permanent injury"29

As much as the lost business and patent dispute, it was Westinghouse's continued intransigence on the safety issue that outraged Edison. By late 1889 Edison's long-standing views about the greater dangers of alternating current had been confirmed by his own tests and independent experiments in France. His rival, he felt, was destroying his business by stealing his patents, installing slapdash systems carrying lethal levels of electricity, and denying the dangers. Overhead wires continued to kill, and Edison feared the deaths might turn the public against all forms of electric lighting. Edison fought back, using the most dramatic means at his disposal—his public support of the electrocution law—to demonstrate the dangers of his competitor's current.30

ON OCTOBER 9, 1889, three days after Edison returned from France, that law survived its first legal challenge: Judge S. Edwin Day of the Cayuga County Court issued a ruling rejecting William Kemmler's appeal. One of the first reasons the judge cited was that, since hanging had been abolished, New York would have no capital punishment law if electrocution were declared unconstitutional. As a result, convictions of all murderers sentenced under the new law might be overturned. Many attorneys argued, to the contrary, that the state would simply revert to the law previously in effect, so that condemned prisoners could be sent to the gallows. But Judge Day raised doubt on the issue, and Kemmler's appeal became shadowed by the specter of prison doors clanging open and murderers strolling free.31

Judge Day had reviewed the transcript of the Kemmler hearings-two bound volumes running to more than 1,000 pages—but he had little to say about it, because his ruling rested upon a more basic question of the separation of governmental powers. As the judge saw it, electrical execution "became law after much more than ordinary consideration and deliberation," and he refused to contradict the legislature and the governor. "Every statute is presumed to be constitu-tional," he wrote, and the burden of proof rested with the party challenging the law. Although the hearing testimony was "conflicting," the judge ruled, Kemmler had not proven that electrical execution was beyond doubt cruel and unusual.32

"It's a victory for us," Harold Brown told the World. "By the way, there have been five deaths in this city from alternating currents since September i."33

*Zenobe-Theophile Gramme was a Belgian who built some of the most advanced generators of the 1870s.